Death in Sicily: Adriano Sack

|SHANE ANDERSON

The French critic and theorist Roland Barthes once advocated for the death of the author.

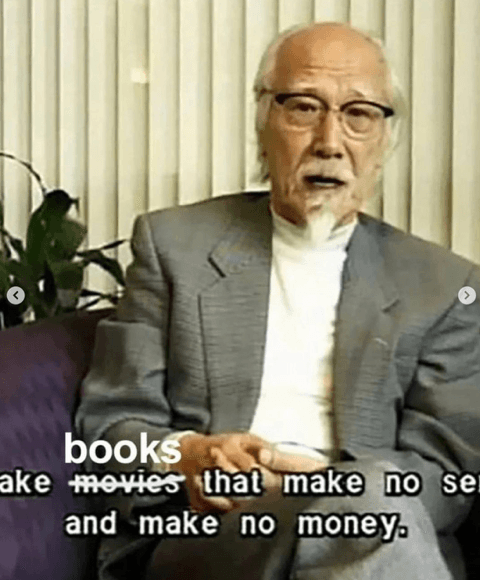

And now, the German critic, writer, and 032c veteran Adriano Sack has done exactly that. In his debut novel Noto, Sack explores what happens to a narrator, Konrad, after his partner, Adriano, dies.

The story begins with Konrad traveling to Sicily with Adriano’s ashes. In recent years, they had purchased a house in the Sicilian village Noto, as had their friends, Jenny and Johannes, who have two children. While dealing with Adriano’s death and the existential questions it raises, Konrad contemplates selling the house but can’t quite bring himself to do it. Noto is a touching story of the toll that mourning takes, but it is also a novel full of lust. Santi, a young, attractive man who breezes through life, joins Konrad on his trip and the two have an affair. With delicate prose, Sack deftly explores both the highs and lows after a life-changing situation. In this interview, Sack talks to Shane Anderson about utopian love, literature’s purpose, and life and death in Sicily.

SHANE ANDERSON: It’s a boring first question but I’m always curious. How long did it take to write the book?

ADRIANO SACK: I had a dream one night in Sicily, and from that night, it took two years.

SA: The novel came to you in a dream?

AS: I know it sounds a bit melodramatic but yes. A couple of years ago, I had this clear idea that I was going to write a novel, but I didn’t know what it was going to be about. Then I went on vacation in Sicily and woke up one night with the story in my head. I knew that there would be a dead guy and another guy mourning him.

SA: It wasn’t just anyone who died though. It was a writer named Adriano who seems to have a lot of similarities with you. Why did you kill yourself in your book?

AS: I had to get rid of myself to become somebody else.

SA: How so?

AS: You know, this question is obviously the first one that pops up. And at some point, I had this idea that I would answer it differently every time. Like Heath Ledger’s Joker who always comes up with a different, terrible story about the scars in his face that make him smile.

The point is, if you come up with something as drastic as someone dying who has the same name as you, then there are probably a number of potential reasons. One is laziness. Another is that I wanted it to be as painful for myself as possible. And another would be that I didn’t want to kill anyone else. But the main reason is that I’ve been writing as a journalist for a long time, and I had been avoiding writing a novel for decades because I thought I didn’t have it in me. It’s not that I didn’t come up with stories, I did it all the time as a style journalist, but then I got to the point where I asked myself: “Is this all I got?” It would of course been easy to use another name, but I emphasized it to symbolically erase the writer I was to become a new writer.

pants CASUAL LEATHER TROUSERS

SA: What interests me though is that you use your first name. A lot of other writers have used stand-ins or abbreviations for their name. I’m thinking of Kafka, Hemingway, Plath, Bolaño—and the list goes on…

AS: The name was actually different when I was writing it. And at some point, I said, “Ok, this guy’s a caricature of myself anyway, so why not call him Adriano?” I was about 80 to 90 percent done with the book when I made that decision.

SA: Are any of the other names in the book real?

AS: Only my dog’s name is the same. The name of the narrator, Konrad, is my middle name.

SA: That surprises me. I had just assumed that all the names were the real names. How close are the characters to the people in your life?

AS: I wouldn’t want to quantify it. But I will say that Konrad is close enough to my husband Frank to make him feel uncomfortable but far enough away so that it’s not a copy of him and he can live with this character in the novel. This is a very old mode for novel writing, of course, where you start with reality and then form it into your reality.

SA: Today, using your own name feels like it would immediately situate the book in autofiction. Was autofiction important for the writing?

AS: I was certainly playing with it. But more than anything, I have this old-fashioned belief that art should cut the ground from under your feet. It should make you feel insecure and raise questions. It should make reality more unstable. I don’t believe in clear answers in literature and my intention was to play with this idea of reality so that readers ask themselves: “What’s real? What isn’t? What’s been changed?”

SA: Why is that old-fashioned?

AS: There’s this idea that you have to clearly position yourself as a writer or artist today. I think people want straight answers nowadays, but I don’t think you can get them from art.

SA: So, art is a question?

AS: It’s not a political statement. For instance, the main relationship in the book is between two men. I wanted to have unproblematic gay love. And I didn’t want to portray this relationship in any way that’s problematic or that’s confronting society or their parents. The relationship is problematic because every relationship is problematic, but not because it’s between two men. And I think you could argue that the way the relationships are handled in the book—between man and woman, man and man, and so on—represents a kind of utopia.

SA: How?

AS: Take the character Santi, who floats between guys and girls. He has the kind of freedom where you don’t have to put yourself in a box and stay there forever. That’s the one small hope I have for life and reality.

SA: This sort of freedom is present in many of the relationships, actually. Take Jenny and Joahnnes’ family. At the start of Noto, they lived according to the traditional nuclear family model, but then when the father gets a job offer in Sicily, they change it.

AS: You need to destroy your family to make it live. And it seems to me that people limit themselves to one thing, one theory, and then that becomes their reality. They don’t allow themselves as much freedom as I think is possible. Utopia might not be the right word, but I want to suggest that there are more possibilities than meet the eye.

SA: On the surface level, the book is about Konrad mourning the loss of Adriano and we follow him on a journey of self-discovery. But it just occurred to me that there’s another way to read the book—namely, that Konrad is mourning the life he could have had if he hadn’t been together with Adriano and is now finally doing the things he could have done before had he not been so “boxed in.”

AS: I write somewhere in the book that in most relationships, there’s a more dominant and flamboyant character and one who is a little more in the background. And the story I was trying to tell was that even though Konrad misses his partner, he becomes freer once he’s gone. It sounds perverse to say you could lose the most important person in your life and gain something, but that’s what I wanted to tell. I deeply believe that all of life is a double-edged sword. That’s one layer of the story. But the other layer is that Konrad fell in love with this young guy Santi. He didn’t really fall deeply in love because he didn’t allow himself to and things turned out differently, but in the end, he loves him more than he could ever expect. What started as infatuation becomes brotherly love.

SA: Another layer of the book is the island. Noto feels like a love letter to Sicily.

AS: It’s a letter of love and hate.

SA: They’re never very far from one another.

AS: True. And you see that here a lot too. There’s this ambiguity towards the island. On the one hand, people here are crazy in love with their island, but they also treat it like shit. It can be kind of depressing at times but there’s something very endearing and almost philosophical about it.

SA: But why Sicily?

AS: Sicily isn’t just some random setting. I’ve never been to a place where life and death are so close to one another. Even from where I am now, I can see Mount Etna on a clear day. Flights were cancelled last week because the volcano erupted, and although there’s no immediate danger to my life on a daily basis, there’s this enormous, uncontrollable force of nature that dominates the entire island. For thousands of years, people have been aware that everything could be destroyed in seconds. And if it isn’t the volcano, then it’s the earthquakes from it.

So, there’s a mindset here that devastation is just around the corner and you never know when it’s going to hit. There’s something very dramatic about that. And, it seemed to me that Sicily fits the story and the almost impossibility to live with the loss of the person you love. The almost impossibility of accepting that the house and family you’ve built can be destroyed by this uncontrollable mountain.

I think being aware that everything is in vain but also knowing that you still have to do it is one of the greatest challenges in life. And that’s somehow what happens to Konrad. His life is in ashes, but he still keeps going. And that’s what people do here as well.

SA: One technique I loved in the book was your use of ellipsis. Often, there’s a big buildup to something important and sometimes the event itself is never explicitly stated, it sort of happens in the off.

AS: Yes, well that’s something I love as a reader. I’d rather be out of breath than being dragged along. I think if you push the Tesla insane button every once in a while, it’s good for a book.

SA: The book not only moves fast, it also has a cyclical nature.

AS: I believe in circles. Circles and symmetries. I love symmetrical architecture, for instance. And I like it when things are mirrored. In a good novel, you feel layers of content, layers of relationships between things and stories that you can’t quite put your finger on, but you know they’re there. It’s like walking through Rome and knowing that there’s all this history underneath you. You don’t need to understand everything, but you need to have the feeling that everything is in the book for a reason.

There’s that famous saying by Chekov that if you put a gun on the stage in the first act then it has to be fired. That might apply to plays and short stories, but I don’t think it’s true for the novel. A novel can have dead ends, promises that are broken, things that lead nowhere. That sort of thing keeps you on your toes. You never know whether something is relevant or if it’s just a side story and I think that makes a novel more fun to read.

So, let’s say you introduce a new character. You not only say that this character had a divorce, was cheated on by her husband, and doesn’t like her son because the son reminds her of her ex-husband, but you also mention that she flies to Naples every month to get her hair done. Does this information keep the story going or is it just random? You could argue that it could be cut, that you don’t really need it, it doesn’t lead anywhere. The only thing you learn is that flying to the hairdresser is the last remains of a glamorous lifestyle. But then, you could say that about every sentence. You could ask: what does it give you? And sometimes it’s a question of affect, where it doesn’t add anything to the story, but it adds maybe some color or texture.

SA: It also adds another layer of symmetry, right? Because while Konrad is moving on with his life after losing his loved one, she is still clinging to her past life.

AS: True!

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON

Related Products

Related Content

Nothing is Linear: Guy Trebay

Writers Who Don’t Understand Their Writing: Travis Jeppesen on Estelle Hoy

Pure Shores: THOMAS LOHR's Gezeiten

RAVE: Before Streetwear There Was Clubwear

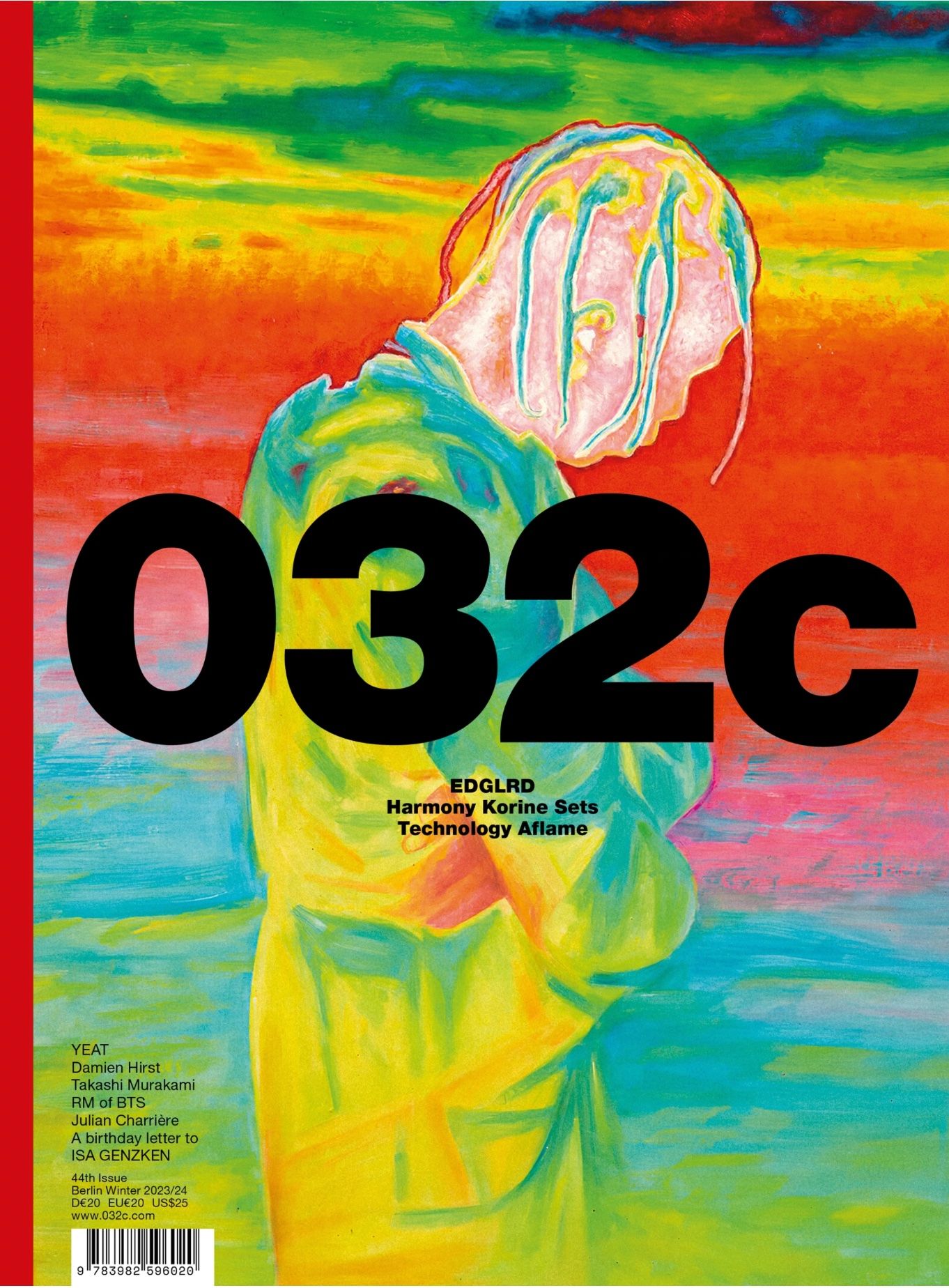

032c Issue #44 “EDGLRD” Winter 2023/24

MATTHEW BARNEY’s Spiritualism of Death and Rebirth

Reinventing Mike Kelley

How Does Design Contribute to Human Catastrophes? Gonzalez Haase AAS

The Politics of Beauty: Tyler Mitchell

From NOAM CHOMSKY to ICE-T: GLEN E. FRIEDMAN’s Book “My Rules” is a Survey in Being Hardcore

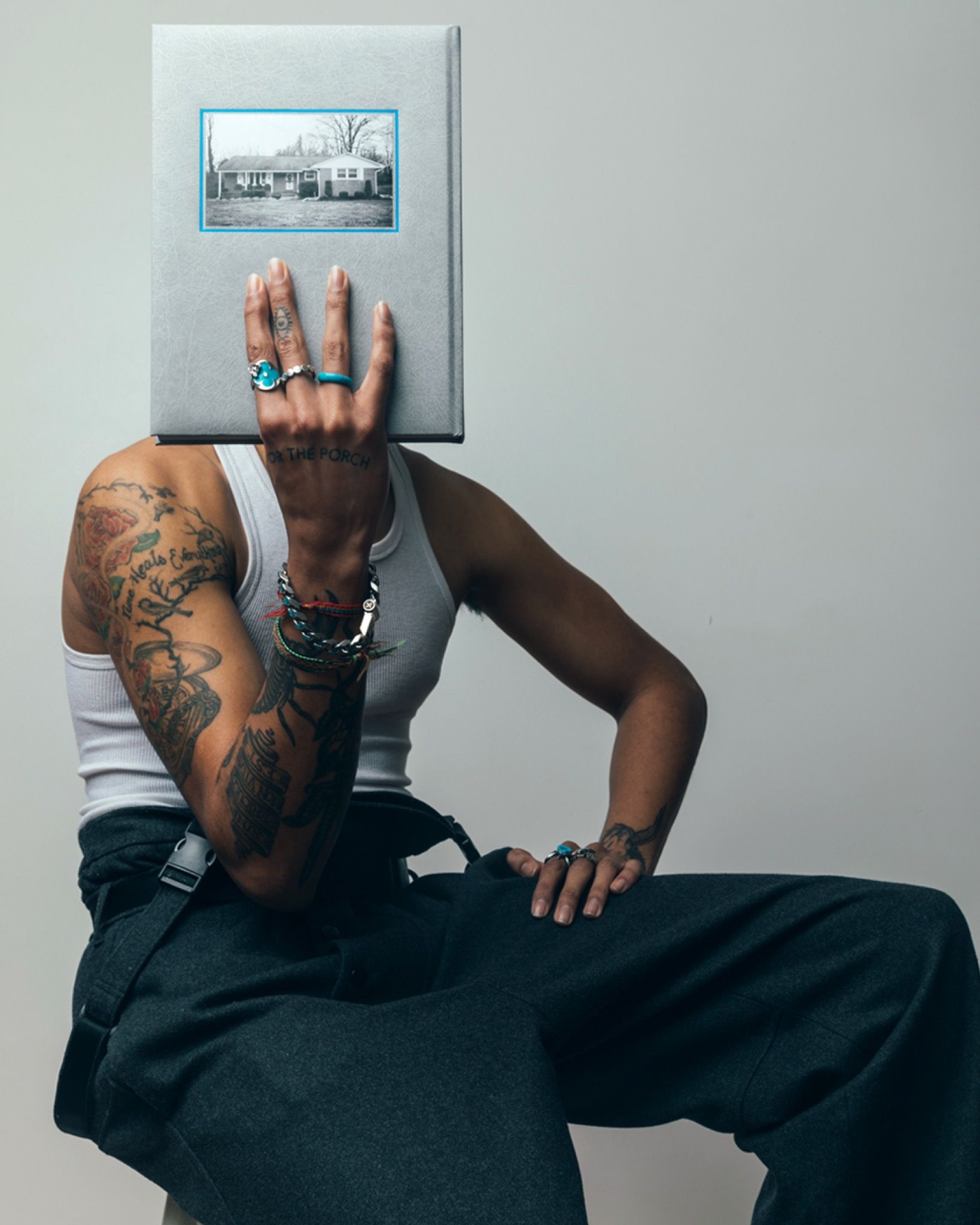

Behind the scenes takes center stage in CAM HICKS’ book debut: For the Porch

An Andy Warhol Foundation Grant That Clearly Wasn’t Enough