Reinventing Mike Kelley

|SHANE ANDERSON

On the occasion of Mike Kelley’s first major retrospective in Europe, we have interviewed K21’s curator, Falk Wolf, who designed the show in Düsseldorf, and are launching a special capsule collection honoring the late artist.

In her memoir Girl in a Band, Kim Gordon describes artist Mike Kelley (1954–2012) as someone who “derived immense pleasure from the unacceptable.” Even if Gordon, a former member of Sonic Youth, was referring here to Kelley’s person and sense of humor, the same is true of his work, which often made use of high and low culture to explore the darker recesses of human experience, systems of belief, and institutional structures. These investigations could take many shapes and forms, either as architectural models of everything he remembers and forgets about the institutions that formed him or as abandoned stuffed animals that are not as innocent as they seem.

In his famous series “Ahh…Youth!” (1991), for instance, the viewer is presented with a series of images of discarded stuffed animals and a self-portrait in an arrangement that is reminiscent of a high school yearbook. But upon closer inspection, these photos also call to mind a series of mugshots of items that had been discarded and that wield unnerving control of our psyches: “You are them,” Kelley once suggested, “whether you like it or not.”

This series has had lasting influence in culture, appearing on the cover of Sonic Youth’s album Dirty (1992) as well as a series of shirts by Supreme. The same can be said of Mike Kelley’s other work, which, as K21’s curator Falk Wolf tells Shane Anderson in this interview, has influenced generations of artists even though they might not be aware of it. It is for this reason that London’s Tate Modern, Paris’ Bourse de Commerce, Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, and Dusseldorf’s K21 have joined forces to show his “provocative and imaginative worlds he created, which continue to resonate over a decade after his passing.”

On the occasion of Kelley's first major retrospective, 032c will launch a special capsule collection in honor of the artist, in collaboration with K21 and the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. The collection will be available at 032c’s first pop up store in Düsseldorf from August 22-24 at K21, in 032c’s store in Berlin and online on 032c.com.

SHANE ANDERSON: Who was Mike Kelley before he became a world-famous artist?

FALK WOLF: Kelley was born in 1954 to a working-class family in Michigan. His parents were Catholic and the descendants of Irish immigrants. Both the working-class and Catholic backgrounds would end up being formative for much of his work. Kelley started art school in Ann Arbor, Michigan where he enjoyed a more traditional training of drawing and painting. Having received his B.A. from there in 1976, he went on to receive an M.F.A. from the California Institute of the Arts, or CalArts, which was one of the most progressive and interesting art schools in the United States at the time. This is where he started to form his early work and received his first sense of recognition, mostly as a performance artist.

SA: That’s interesting because I feel like he’s mostly known for his installations and objects today.

FW: You know, Kelley reinvented himself as an artist three or four times during his career and made the shift to exhibition objects in the early to mid-1980s. Although he made objects before, those were strongly linked to his performances. Even the birdhouses [such as, A Bird Always Builds a Nest in His House (1978) and Gothic Birdhouse (1978)], which can be seen as a pun on minimal sculpture, were linked to his performance works. I think that changed with the stuffed animal works because those were conceived as autonomous sculptures.

SA: Does anything unite the early work to the stuffed animals?

FW: One of the leitmotifs of his work is the notion of adolescence, which already appears in the work Poltergeist from 1978. There, he explicitly linked artistic practice to the state of adolescence in that they’re both in a transitional state. Kelley suggested that an adolescent is a dysfunctional adult and in turn art is a dysfunctional reality. Take, for example, the “Arena” series, which are stuffed animals and blankets that look like cute relics of childhood. They’re very positive at first glance but if you look closer, there’s something uncanny going on.

SA: Correct me if I’m wrong but you seem to be suggesting that the pieces have something of adolescence in them.

FW: In a way, they are a product of adolescence, materially speaking. The stuffed animals only ended up in Kelley’s work because they had been abandoned by young adults who had made a transition in growing up.

SA: And then they’re adolescent in that they address adult themes but use childhood means. I’m thinking of Arena #10 (Dogs), where the stuffed animal dogs seem to be having an orgy.

FW: Absolutely. And sex is another big theme. It already appears in early works, such as Monkey Island [1981–5]. Then, at the time he made the stuffed animal pieces, people said that these must be about child abuse. People wondered what was being hidden underneath the blankets of childhood and they even made the supposition that he himself might have been abused as a child. He rejected both of these claims and said that such interpretations were a huge surprise to him. Personally, I’m not sure that I believe this.

SA: Do you mean you think he was sexually abused?

FW: No, I mean that I doubt that this interpretation could have been a surprise. He was a very reflective artist and was very deliberate with what he was doing.

SA: Child abuse in the Catholic Church was definitely a big topic during the 1990s. I remember seeing things on TV as a kid. Perhaps he was reacting to this?

FW: This would be speculation, the first stuffed animal toys appeared in the mid-1980s. But he did start from real experiences. And this is true for all of his works about belief systems—such as, spiritualism, pop culture, or capitalism. He thought, for instance, that beliefs about alien abductions or conspiracy theories were real. Not in the sense that they should be believed but that people do believe in them. And since so many people believe in them, he understood them as being formative for society. His strategy was to take them seriously, taking their metaphors literally. By doing this, the inherent contradictions of the belief systems are revealed—as is their absurdity.

SA: You mentioned that Kelley reinvented himself a number of times. What was the next iteration?

FW: Most of the work Kelley did from 1995 on was spawned from this rumor of being abused as a child. He thought that he needed to think about what abuse could have been for him and his answer was his strict Catholic upbringing and art education as such. Education, memory, and forgetting became the main preoccupations during this time, which was a long-term research into a “shared culture of abuse” as he put it. The formative work of the 1990s is Educational Complex. It consists of architectural models of all the schools he went to, including his parents’ home, his kindergarten, primary school, high schools, and colleges, and this model is crowned by CalArts which even has a larger scale than everything else. The title Educational Complex has a threefold meaning, addressing the complex of the educational system, the complex as a psychological phenomenon that might be induced by an educational system, and the complex as the architectural setting, the buildings that everything is taking place in. Today it can be seen in the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Unfortunately, it is not in our exhibition because it is too fragile to travel.

By the end of this period, he used every artistic medium that was available to him at the time while continuing to be very reflective about his situation and about that of the audience. To my mind, this makes him one of the most complete artists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

SA: Is this why you’re doing a Mike Kelley exhibition now?

FW: We thought it was important to bring his work to a new stage since there hadn’t been any large one person shows in Europe in the past ten years. The last major show was the retrospective he was planning shortly before his untimely death and that only opened afterwards. As a consequence, the younger generation hasn’t really had him on their radar in a conscious way. I would say many young art students are highly influenced by Kelley without perhaps being aware that they are influenced by him. And I also think that if you want to study contemporary art, then all you need to study is Mike Kelley. Everything is there. And I think this is still true even though he’s probably one of the last non-digital artists, as Susanne Gaensheimer recently observed.

A lot has changed in the last decade, of course, in terms of technology, politics, and ideology. Yet, the dominant themes that he reflected on in his work are still questions of our times. In fact, conspiracy theories are probably even more important today than they were in the 1990s. The dominance of right-wing belief systems has increased and this also something that Kelley’s work addresses.

SA: Questions of gender come up, too.

FW: Yes, he was constantly trying to undermine the role of men in society and often subverted masculinity. There’s the Superman Recites Selections from The Bell Jar and Other Works by Sylvia Plath, for instance, where Superman reads works from the feminist author and deconstructs male dominance.

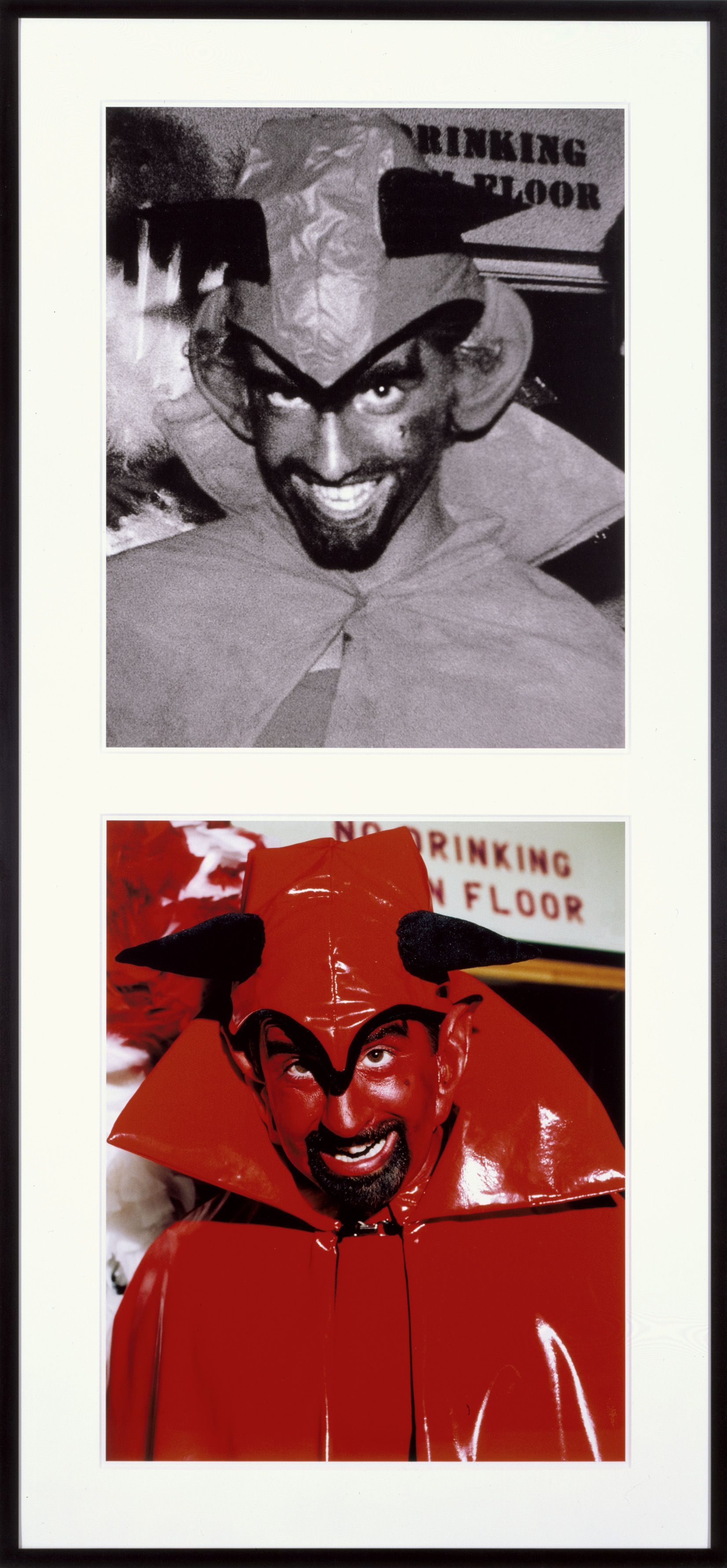

There’s also his text called “Cross Gender/Cross Genre” (1999), where he thinks about cross-gender phenomena since the 1960s in a way that was not at all common for white male artists at the time. In the catalogue for the exhibition, Jack Halberstam rightly suggests that this text is not up to date and might not be radical enough from today’s point of view since it mainly focuses on male artists like Jack Smith, Alice Cooper, Mick Jagger, or David Bowie, but this probably misses the fact that it was pretty radical at the time coming from a successful white male artist.

SA: Another thing we haven’t addressed is the humor in the work. Superman reading Sylvia Plath is just flat out funny. There’s also this humorous moment in the exhibition in K21, where, if you come down the elevator, you’re met with a hand painted sign that reads “Auditions” and has an arrow pointing into the exhibition space. I felt like it was a great introduction to the work as it implicated the viewer into the show.

FW: To me, that work seemed to be in line with how Kelley thought about exhibition making. There are other works by Kelley where you have to crawl beneath paintings or through tunnels and into boxes. He made lots of work that reflected on the role of the exhibition visitor.

It’s important to say here that the show was curated by Catherine Wood and Fiontán Moran at the Tate Modern. They are the authors of the show’s concept, and I’m only the author of how you see it at K21. The architecture of the space in Düsseldorf is such that if you come down the stairs, you’re in the middle of the room and it’s hard to force the visitor to go on a linear path through the exhibition. Such a linear path might not be the best aesthetic way to show Kelley’s work anyway, since there was always a continuum of ideas that jump back and forth—in the 1990s, for instance, he went back and redid some of his works as a student. So, the idea was to give the visitor the impression that you’re entering Mike Kelley’s brain when you come down the stairs and you already see and hear many different things at the same time. Acoustically and visually, it’s overwhelming, and it’s meant to be.

SA: The exhibition design is interesting because you can either walk from one room to another in a circle and discover thematic resonances between the rooms or you can choose to follow the chapters of the exhibition, which then means you have to walk from one side of the exhibition to another and then back again.

FW: That’s one way of reading it and another way would be that we’ve got white walls and dark grey walls and those are two entirely different ways of presenting things. The one is for exhibition works and the other is for more theatrical or staged works and Mike Kelley’s work is about performing and about exhibiting. This is perhaps more museological concern, but both are constructed realities, and it was important to have those two strands of performing and exhibiting both divided and connected because there are many works that have a performative background and end up as exhibition pieces. In fact, this is also reflected in the title of the exhibition, “Ghost and Spirit.” The title comes from a scripted performance piece that was never performed. It is now exhibited for the first time and can be read by the visitors.

In the text, Kelley was thinking about the exhibition space. He makes the distinction between a ghost, who is a disappeared person, and a spirit, which has influence on others. The artist in an exhibition space is not present, is a ghost. But the question for the artist is how to have an influence on people and how to become a spirit.

SA: The title also puts forward the topic of spirituality, which might not be something you immediately relate to him, but which is there, right?

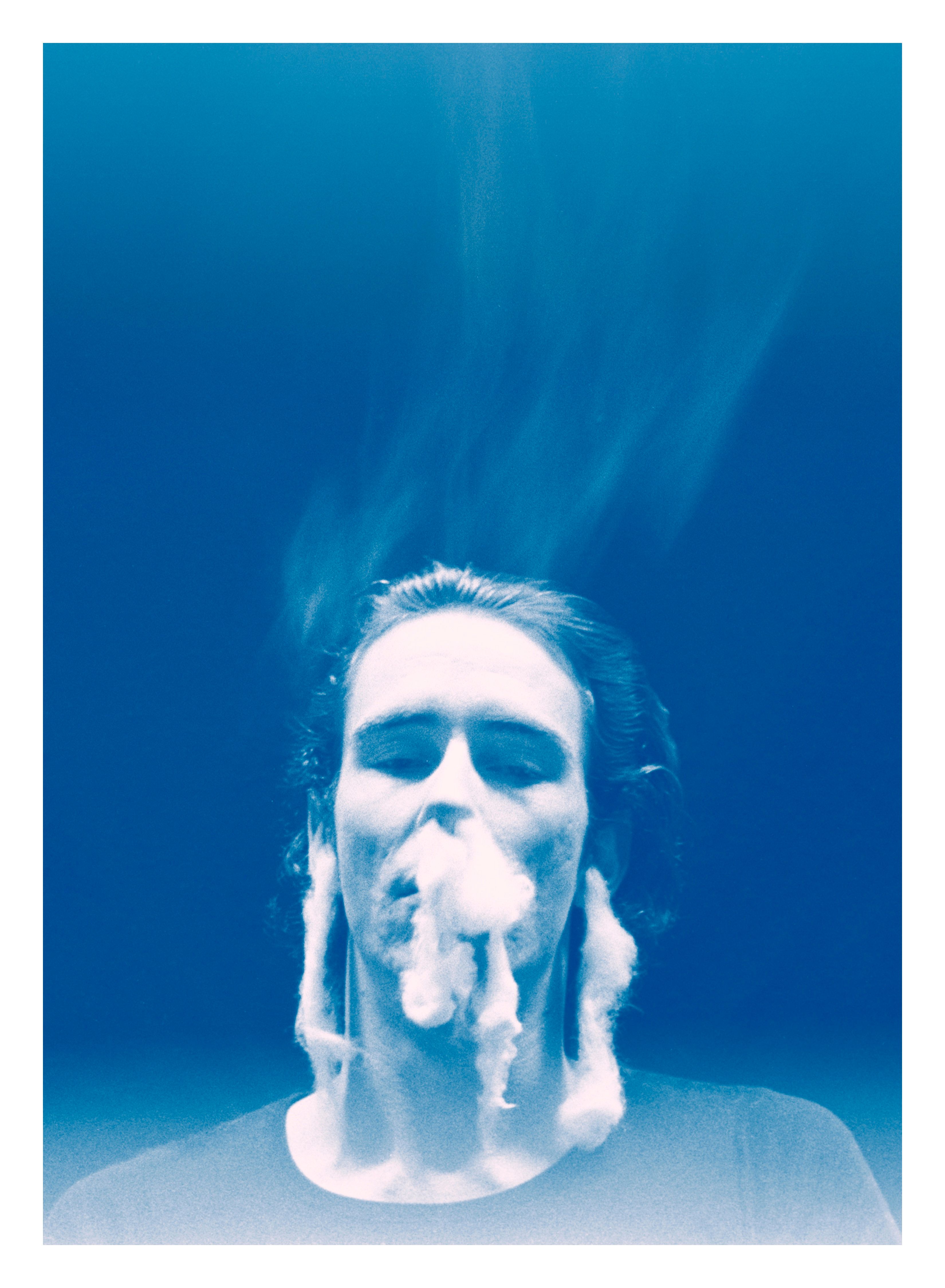

FW: It’s predominantly there in the early pieces but he goes back to it throughout his career. The belief in spiritism, making contact to dead people, and all of that is something he ends up linking to the belief in aliens and reports about alien abductions in the later work. To me, it’s part of what I was saying before. He takes it very seriously that people believe in them. But on the other hand, he reveals their absurdity by taking all the metaphors so literally. For example, he uses the idea of ectoplasm in The Poltergeist. Ectoplasm is believed to be a substance that comes out of the orifices of mediums when they make contact with the spirit world. It’s a physical reaction to the spiritual, which early spiritists in the 19th century believed in and tried to make visible in photography. At the time, it was described as a fatty substance. And what Mike Kelley does with this metaphor is that he describes making contact with spirits as a weight loss program. He says that if you become lighter after pouring out this fatty substance, then you’ll also be closer to the spirits because you don’t weigh as much. So again, on the surface level, he takes the language seriously and reads it literally until it becomes absurd. And this is something he did with basically every belief system.

SA: I’d like to push back on this actually. Because, if I understand you correctly, you’re saying he was doing this more as a way to investigate belief systems from the outside. But it doesn’t seem to me that he was only looking at things with his tongue in his cheek and a judgmental viewpoint. There seems to be real curiosity about the unknown and a sense of searching.

FW: This interpretation is possible, but I don’t think I’m the best person to talk about what Mike Kelley actually thought and felt and believed. I’m more inclined to read his work as a sort of artistic sociologist of myths, belief systems, and conspiracy theories. To me, his work is utterly anti-metaphysical at its core, he sees reality as a social reality and all of these things are real in so far as they’re part of our social reality.

SA: Yes, but there are hundreds of things that make up our social reality that I as a writer don’t feel drawn to address. I only investigate those that I myself have questions about. And what you said about Kelley working from experience and his long interest in belief structures would suggest to me that there were questions there. Kelley didn’t seem to be someone who was just looking at the world from a birds-eye-perspective but as someone who was part of the world.

FW: I do not mean to suggest that he is looking at everything from a distance. He certainly does not establish an Archimedean point. On the contrary, it is very palpable in his work that Mike Kelley was born into a specific situation. He’s a white, male artist raised in the 1950s to a Catholic working-class family—his mid-career exhibition at the Whitney Museum was even called “Catholic Tastes.” Even though, as a fallen Catholic, he referred to much of it as “Christian crap,” he definitely acknowledged that he was influenced by it and, as a person, couldn’t wipe out that influence. I think that was important. His point of view as being Mike Kelley, as the person he was, is extremely important. But this did not keep him from playing with his biography, from fictionalizing it in more or less obvious ways.

SA: We didn’t get to the fourth iteration of his career, which means that people will have to see the show in Düsseldorf, London, or Stockholm to get a better sense of it.

Explore 032c’s special capsule collection honoring Mike Kelley here.

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON