RAVE: Before Streetwear There Was Clubwear

|Adriano Sack

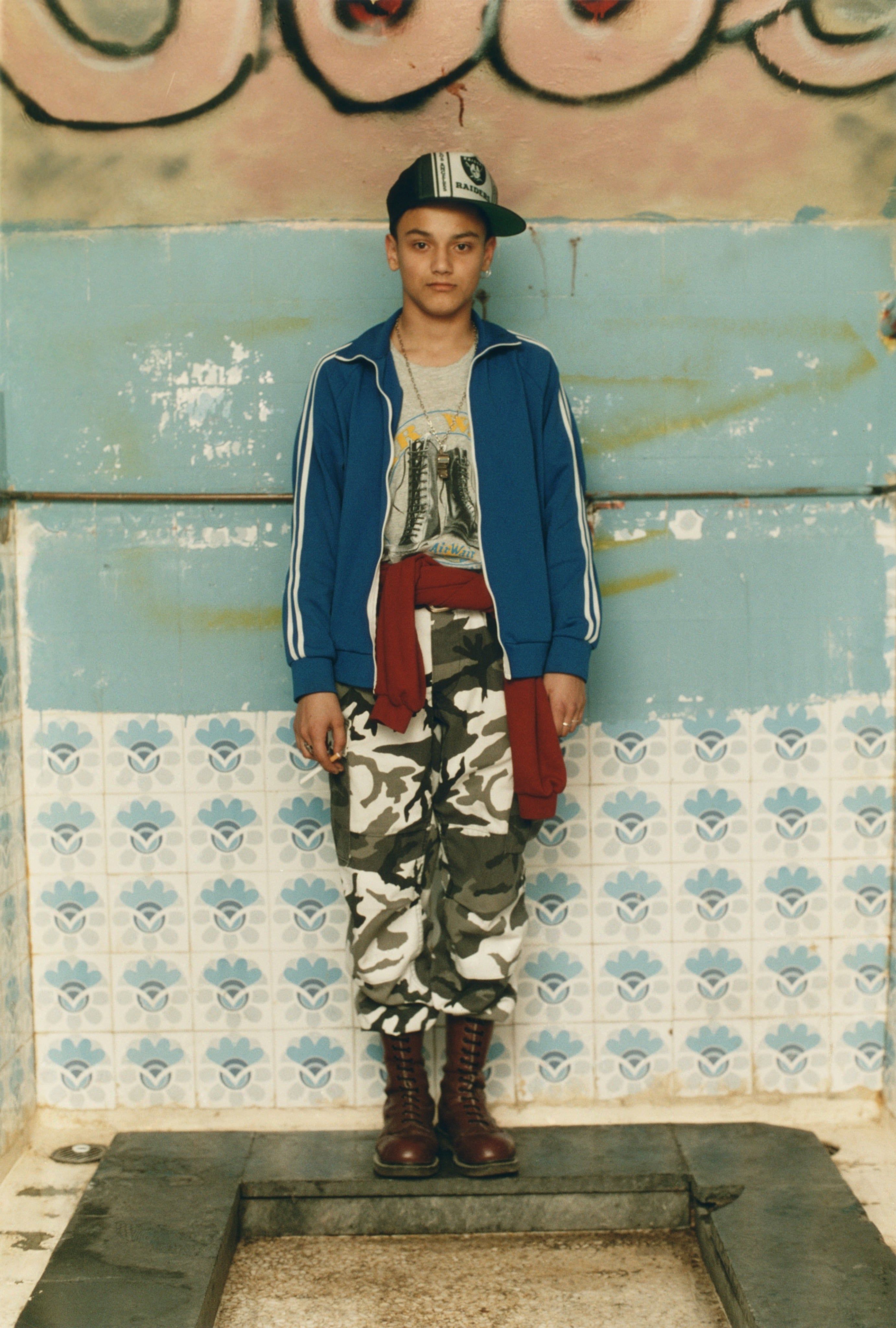

The boy is 16 years old – maybe only 14 – standing in front of a colorful blue, paint-smeared wall. He is wearing baggy camo pants, wine-red combat boots, a t-shirt, keys slung around his neck, and an old dark blue Adidas tracksuit top, his cap tilted on his head.

Wolfgang Tillmans photographed Christos in 1992. The image was most likely published in i-D, sometime in the 1990s. During the early years of his career, the artist documented the nightlife he encountered in Hamburg, London, and across Europe. i-D was, maybe even more than its rival The Face, a central organ for the fashions that emerged not from the catwalks, but from the clubs and the streets in front of them.

I worked at a club in the early 1990s: the gay disco Front on Heidenkampsweg in Hamburg. It was a small, fairly radical operation. The doorman was a taciturn mustachioed Tom of Finland type. There was a stash of baseball bats behind the cash register in case of hate attacks. DJs smoked joints in the booth (though these were strictly prohibited), and by 1.30am condensation dripped from the ceiling. All kinds of sex were had in the toilets, though the hardest sex was reserved for the private basement quarters. Drug dealers got free drinks all night – something I hadn’t caught onto at the time. What I did understand was the magic of nightlife: a world of excess, dissolution and maybe even self-destruction – which was exactly why essential art movements, friendships, and fashion styles were born out of it.

It might sound romantic and incredibly far away, but back then I cut out the picture of “Christos” and pasted it on my kitchen wall. His lost and defiant gaze seemed to describe exactly how nightlife can claim and seduce a person. His look was programmatic. It probably didn’t cost more than a few drachmas, but still it connected some of the most important style elements of 90s clubwear: uniforms, sportswear, and skate culture. This is what the boys wore at parties and raves, a way of dressing that was the equivalent of mixing music: appropriation, de- and recontextualization, creation through combination – a cultural technique that has outlasted rave culture itself. It was the way rave- and clubwear was conceived, consumed, and communicated that made it the last youth culture to develop without global brands steering its direction and cashing in. Ironically, or perhaps inevitably, today Christos is part of a private collection – that of Christian and Karen Boros, who show their art in a bunker that was once home to Berlin’s most hardcore parties between 1992 and 1996.

It isn’t surprising that clubwear is an important reference for fashion designers today. Some day, 2018 may become known as the year in which the triumphant march of streetwear came to a close. It is notable that nobody wants to use the term anymore, as its figureheads ascend the ranks of high fashion, and creative directors go back to their archives in search of fresh juice. Woolrich recently began a collaboration with the British designer Jeff Griffin, whose signatures are camouflage and club references. After some economic fall-off, Prada is now reacquainting itself with perhaps the most important phase of its history: sporty elegance, directly derived from vulgar futurism and techno culture. As for new blood, photographer Benjamin Alexander Huseby and fashion designer Serhat Ișik are advancing a similar aesthetic with their brand GmbH, with the added suggestion of sex: carefully placed zippers, form-fitting cuts, and clothing made from PVC or fine-rib cotton. Finally, with sneakers – a rave essential – the luxury industry has found a product that is to the men’s market what handbags are to womenswear: an endlessly variable gateway drug with a heavenly margin that doesn’t present the ideological or psychological issues seen elsewhere in fashion. Whether a man needs a tailored suit, an elegant bag, or an expensive watch is a matter of taste. But a sneaker is as self-evidently masculine as a car used to be.

“In the beginning you saw vacuum cleaner backpacks and breathing masks in the clubs,” Alexander Branczyk says over tea in a snug courtyard in Berlin’s Mitte district. Branczyk lives here now and runs the agency Xplicit, but from 1992 to 1997 he was art director of the techno magazine Frontpage. Having originally come to Berlin as a graphic designer to work with Meta-Design, known for its co-founder Erik Spiekermann’s obsessive preoccupation with typography, Branczyk created the font and logo of the Love Parade, thus influencing the entire visual appearance of German club culture. Nightlife in the years following German Reunification fascinated the young designer – the famous Leerstellen [empty spaces] in Berlin where one could simply start a club in a desolate industrial building, with its very own sound. It seemed as though, for the first time, genuine German pop music was being created. Though techno had its roots in Detroit (and in Belgium, and with Kraftwerk), it found its blunt, hymn-like qualities in Berlin and partly in Frankfurt. “Techno translated the character of the Germans – the angry, belligerent combat animal – into pop culture,” says Ulf Poschardt, editor in chief of Die Welt, who published an obsessively substantiated analysis of electronic dance music, DJ Culture, in 1995.

Through friends in the nightlife scene, Branczyk met Jürgen Lahrmann, a bulldozer of charisma who founded a kind of techno party-program zine called Frontpage in Frankfurt, then came to Berlin to make something bigger out of it. “We are both originally from Oberursel [in Hesse]. Terrorists and nazis are from there usually. His mother was a math teacher at my school,” Branczyk says of the unusual partnership. In the years that followed, Branczyk handled his agency work during the day and took control of the most influential lifestyle magazine of the 90s at night. He worked on Frontpage under the pen name “czyk,” an illustration of the romanticism of rave culture, with its cold futurism and demonstrative modesty, the dream being to melt together with the machine in a mechanical dance. “An overcrowded Mackintosh desktop with thousands of open windows,” is how Branczyk describes the visual direction of the magazine. He only used fonts he had developed himself, layered articles on top of each other, let typography bleed into text, blurred and pixelated the photos on purpose, and made the record reviews and party reports ridiculously small. “Our principle was: we do not shorten texts. We make the font as small as it has to be for the text to fit,” Branczyk explains. Like many aesthetic movements, the techno look was a revolt against the establishment. In this case, it was a reaction to the immaculate style of British art director Neville Brody, who was responsible for The Face. Even today, the ruthless nature of the design is thrilling – Ray Gun was the only American magazine to take a similar path. “Nobody liked it except for the readers,” Branczyk says. “Frontpage has been left standing uncommented upon in the landscape, but it was a monumental work.”

In terms of fashion, styles crashed into each other in techno clubs. Branczyk describes people wearing parts of vacuum cleaners for looks that were the Burning Man costumes of the early rave years. Buckle on something discarded somewhere in the streets and you were ready for the night. This led to the popularity of garbage collector vests, which became a hated Love Parade cliché. “The fur stuff, the dyed hair, awful,” recalls Poschardt, who once drove a Porsche from Munich to Berlin in total look Stüssy for a magazine feature on Love Parade style. “Road sweepers and whistles. I always thought of ADAC [General German Automobile Club] members. Techno ends bluntly.” Of course, today the signal color look is found only slightly altered in the reflective jackets that Raf Simons designed for Calvin Klein, or in the neon-colored hardware store gloves by Virgil Abloh for Louis Vuitton (as well as the junk plastic chains that adorn a suite of his bags).

What follows is a map of the key constituents, ideals, and reference points of CLUBWEAR:

1. WAR

Camouflage trousers, cargo pants, combat boots, gas masks: uniforms have always been a reference point for fashion, especially in menswear. The clothing was indestructible and looked just as wild before an all-nighter as it did after one. Back then, partying was often a survival practice. “The club Planet was on Köpenicker Straße first, and then later in Alt Stralau, far in the East where there was no street lighting,” says creative director Cathy Boom, who opened the concept store Groupie Deluxe in Berlin’s Schöneberg district in 1994. “Once you were there, you weren’t able to leave.” Klaus Stockhausen, who in the early 90s had just given up his DJ job to become a stylist, concurs: “Come rain or come shine, you partied – so it was also about protection.” Brands including Australian Blundstone, which sold protective shoes, and the US label Carhartt, which gained popularity at the time, were closely linked to military apparel. The stuff was cheap and connected the movement to the anti-establishment tradition of punk. Techno was a subversive culture, especially in its formative years. Theoretically, anyone with a computer could produce a global hit, which led to fantasies about the salvation from capital envisioned by Karl Marx. “The best t-shirt was from Underground Resistance,” says Poschardt. “It just said: ‘Music for those who know,’ a wonderfully elitist gesture.” Of course, military clothing suited the hard 4/4 beats that would not cushion the soul-derived groove of house. Because techno was, essentially, accelerated marching music, its iconography was martial. Parties were titled Mayday or Teknozid. Favored motifs for t-shirts and flyers were hand grenades, launching platforms, or the radioactive symbol. “For people like DJ Tanith, it always had to get harder,” says Poschardt. “He would have preferred to arrive at the Love Parade in a tank.”

2. Postmodernism

Ciphers from consumer and pop history were excerpted, newly combined, and reinterpreted. The Japanese label Hysteric Glamour, for example, copied motifs from Blaxploitation movie posters of the 1970s and printed them on t-shirts. An early fan shirt for Munich’s DJ Hell displayed the logo and lettering of the oil corporation Shell (leaving out the first letter “S”). The zine Flyer satirized a different brand on every cover. They wrote their own name in the typography of the soft drink Fanta, and drew a few stylized orange tree leaves beneath it. “It’s a Japanese approach to pop culture,” Boom says. “Disrespectful, unbiased, without fear of history.” Boom sold Hysteric Glamour shirts back then, as well as Converse shoes with platform soles which her partner, who conveniently worked as a stewardess, brought back from her trips to Tokyo, along with products by X Large, the Beastie Boys’ streetwear label, from trips to New York. The humor that underpins this strategy of appropriation seems, depending on one’s taste, anything from innocent to silly. But the same mechanics of implausibility are visible in countless collaborations today, whether it be decorated Crocs by Balenciaga, or grotesque over- the-knee Ugg Boots by Y/Project.

3. DIY

When ravers needed an entrance to the Halle Weißensee in Berlin, the boss of techno record label Low Spirit simply blew a hole through the wall. Fashion was similarly influenced by these same ideals of accessibility, individualism, and doing it yourself. “Since the 1980s, people had been combining clothes in the ‘wrong’ way: cheap and expensive, old and new, full of contradictions, customized,” says Inga Humpe – a popstar who witnessed the rise of electronic dance music in London and Berlin, and later formed the duo 2raumwohnung, which successfully merged pop hooks with an after-hours sensibility. “Every movement starts on the ground, with the people,” she says. Often, DIY was an economic necessity. But elsewhere it was a political gesture. In the London clubland of the 80s, performer Leigh Bowery, a companion of Boy George and Alexander McQueen, squeezed his already intimidating body into costumes that made your average drag queen look like a square. As elaborate as his performances were, they contained a simple message: do what you want and do it yourself. “There were fantastic local differences within the club scene,” says Dutch photographer Ari Versluis, who partied at the Berlin club E-Werk and Club Now & Wow in Rotterdam. “There was no media to homogenize the style. It was less about money, more about ideas, attitude, friends, and choices,” though it was the “uniformed identity to the max” at gabber club Energy Hall in Amsterdam that inspired him to begin his photographic study Exactitudes. Fashion designer Xuly Bët was one of the few “real” designers whose concepts corresponded with club culture, looking like piles of fabric from a charity collection that had been shredded and sewn back together. The Berliner Frank Schütte, whose label 3000 caused some excitement, used this collage technique as well. Shortly before he fled the city with a large amount of debt hanging over his head, he showed a collection of slick dark blue nylon uniforms. Schütte had lost track of his career in a drug rush, but aesthetically he was on the same road that Prada followed back to fashion’s Mount Olympus this year. Schütte and his partner Stefan Loy made an impressive comeback as designers in Los Angeles, where they counted superstars Britney Spears and Angelina Jolie among their customers. In 2007, they closed their business, moved to Ibiza, and opened a small boutique. A surprisingly happy, yet mellow ending.

4. SEX

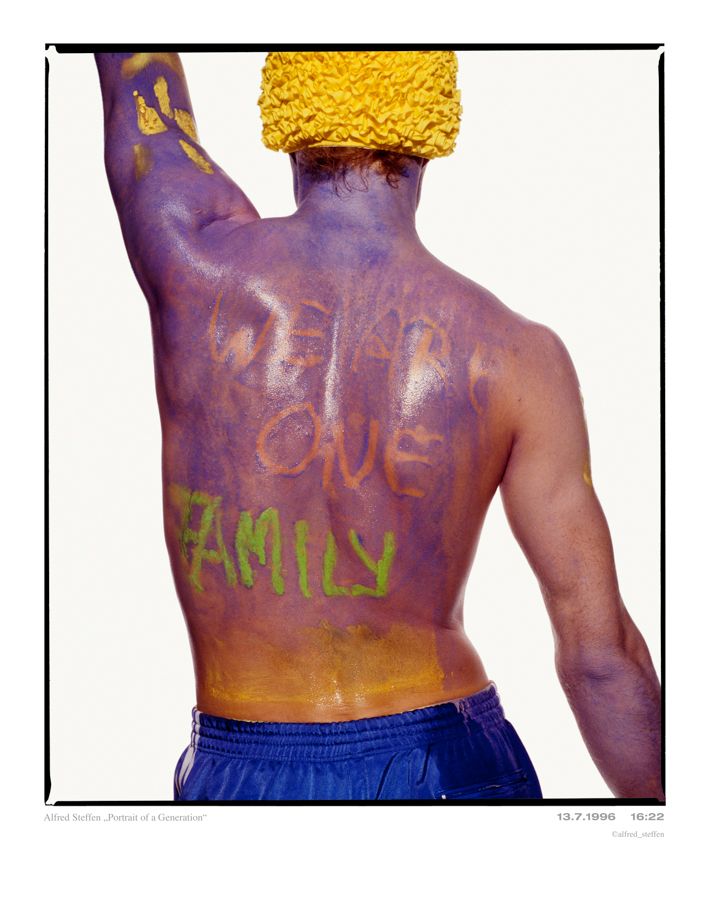

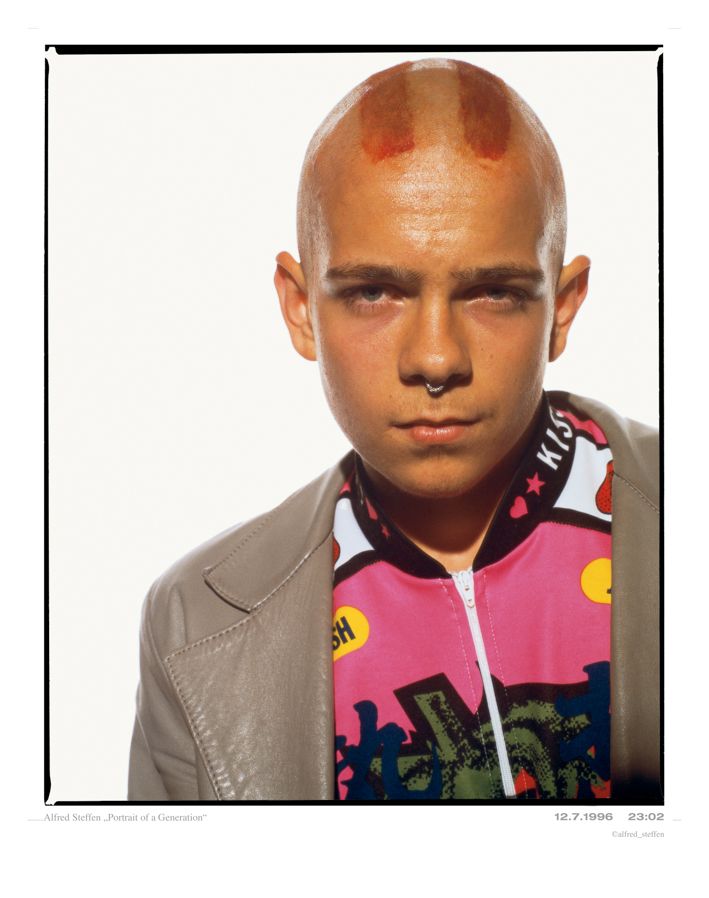

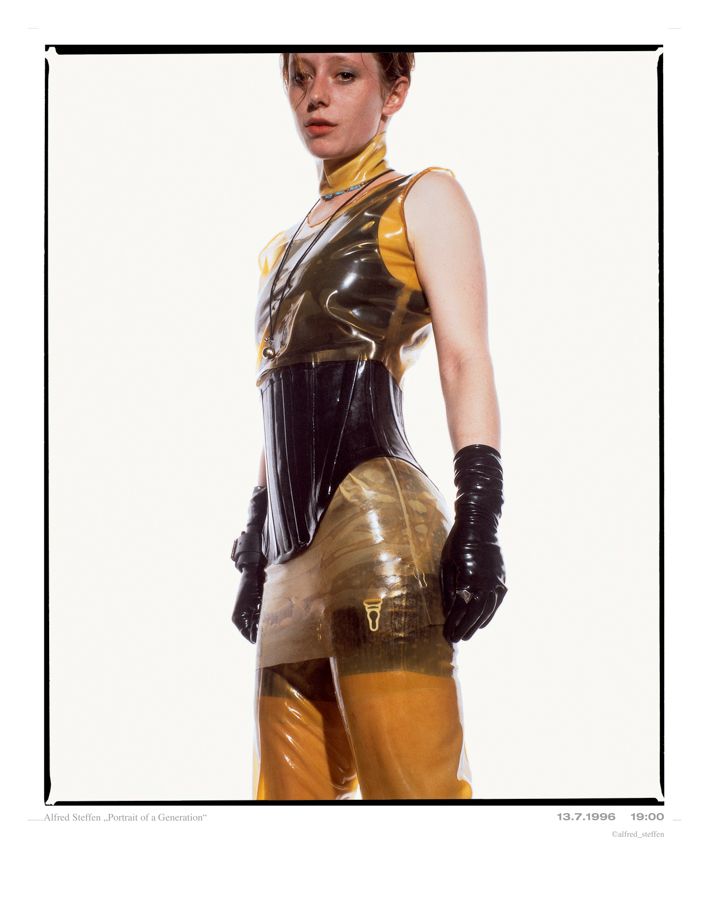

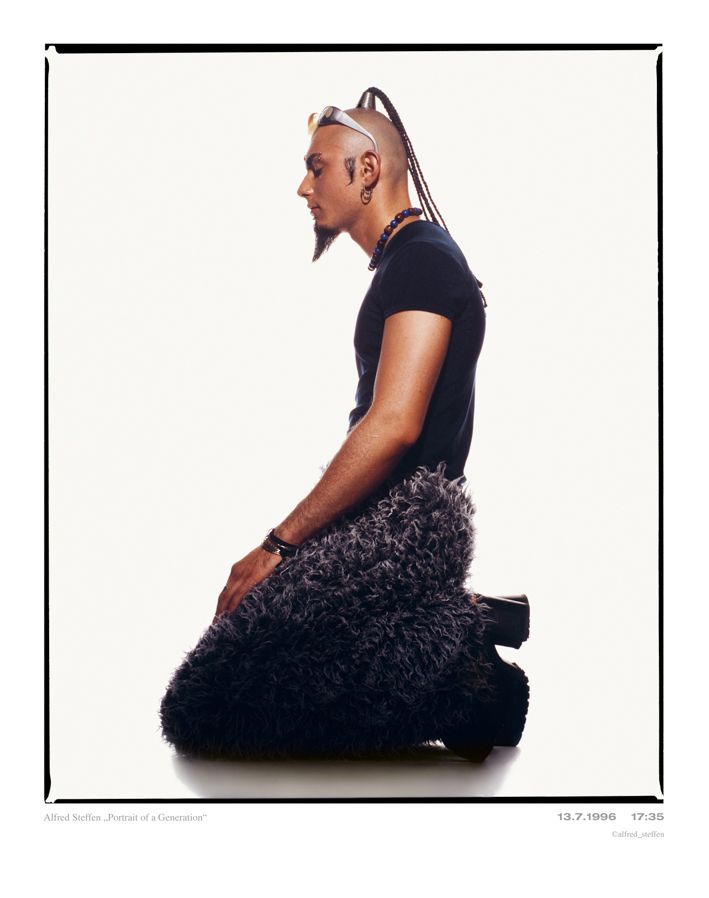

“At 4.30 in the morning, amid the fog and steam at Tresor, the dancers wore t-shirts. Or no t-shirts. There wasn’t really a recognizable fashion concept,” Poschardt recalls. Nudity may be the most important stylistic element of clubwear. Photographer Alfred Steffen took pictures of 250 people at the 1996 Love Parade for his book Portrait of a Generation, which shows colorful hair, patent leather pants, platform shoes, piercings, and most importantly, lots of skin. “As a woman, you were either sexy or a freak – somehow I managed to be both,” says Humpe. The look for girls included tight t-shirts, transparent or crop tops, or both, short skirts or tight pants, faux fur bras, and expressive shoes – which led to the unlikely success of the German brand Buffalo. It was the DJ Sven Väth who first elevated his Adidas sneakers with chunky platforms, a move the otherwise tame brand Buffalo copied, making their shoes at once bestsellers and objects of hate. It was Jürgen Lahrmann who named the “Octopussies”: a kind of three-person girl band without any songs, stylized in fashion editorials and party coverage. They were somewhere between “it” girls and sex objects – a clear demonstration of the male gaze within the milieu not without wider cultural consequences: the comic book figure (and later movie hero) Tank Girl, with her camouflage pants, tank tops, spiky hair, and machine gun, was typologically once a raver. Men also liberated themselves by plundering gay culture: revealing their own bodies, wearing tight clothes, and playing with stereotypes just like the Village People did. When looking at the images in Steffen’s book, it becomes clear that gender fluidity was not an invention of the third millennium. Modifying, piercing, and inking one’s body, and building it up in the gym, had already infiltrated the mainstream back then.

5. Science Fiction

The biggest fetish object of the club and electronic music scene might have been the computer. Even if music was still being played on vinyl in clubs – digitization was not quite yet a reality – the future was as seductive as it had been around the time of the moon landing. This fascination is why the lettering on sweatshirts was printed in almost illegible fake computer fonts. “Kiss the Future” was one of the slogans on a polyester longsleeve by the Belgian designer Walter van Beirendonck, whose label Wild and Lethal Trash exaggerated club culture and brought it back to fashion, with its loud colors and tasteless comic book designs. One of the most visible labels at the time was Sabotage, from Mannheim, a town of 400,000 in Southwest Germany with an active club scene. Says Sabotage founder Michael Dannroth, who had been producing rather nondescript clothes under the label since 1982: “I was always in love with the technological and industrial aesthetic. In the beginning we hadn’t been aiming at the new scene that was emerging in the late 80s, but then we noticed a synchronicity.” In 1992, Dannroth hired graphic designers from the agency Formgeber, Rolf Rinklin and Jochen Eeuwyk (who were ravers themselves), to create a futuristic typography – derived from Suzuki or NASA, depending on who you ask – with a logo that looked like a molecule. In the following years, Dannroth formed a loose network of artists who contributed to the brand’s visual identity, building booths for fashion fairs and producing Sabotage-related artefacts that fell somewhere between tribal art and H. R. Giger. Sabotage broke every rule of fashion retail: they did not communicate with the press, they produced very pricey basics, worked with a new, inexperienced network of wholesale dealers, tried new fabrics constantly, and destroyed their clothes, such as the legendary “Destroyed Washed Sweatshirt,” before putting them on sale. Dannroth worked with the same Italian factory that produced Stone Island, he sponsored big Mayday parties, and advertised in club zines – not least of all Frontpage. It was a trendy label, but its approach was radical. One sweatshirt had fibers containing ceramics that were supposed to protect ravers from overheating. There was a jacket made of metal mesh traditionally used for silkscreen printing (sold for the unheard of price of 1000 deutsche marks). The parallel to the euphoria of rave was grunge: a pessimistic attitude toward the world, stylistically regressive in music and fashion (if you disregard Kurt Cobain’s performances in women’s dresses) – flannel shirts instead of patent leather pants. But that was a different universe.

“I was totally into techno,” Rinklin says of his work for Sabotage. “I did not care for couture.” In hindsight, clubwear derived its power and appeal from the same elements that made techno and rave culture so unique: you had to be physically present. “You couldn’t listen to it on the radio,” Humpe says. “You had to be in the club.”

The clothes weren’t available online or at the local department store. You had to track them down. Wearing them made you the member of an exclusive club, one that rested on dedication and knowledge. “In the 90s, nobody looked back,” Rinklin adds. Ravers staggered into a changing world and their clothing aimed to express that. They saw the future. And they kissed it.

Credits

- Text: Adriano Sack

- Photography: Alfred Steffen, "Portrait of a Generation" photographed in Berlin at the Love Parade, 1996, ©Alfred Steffen