Nothing is Linear: Guy Trebay

|SHANE ANDERSON

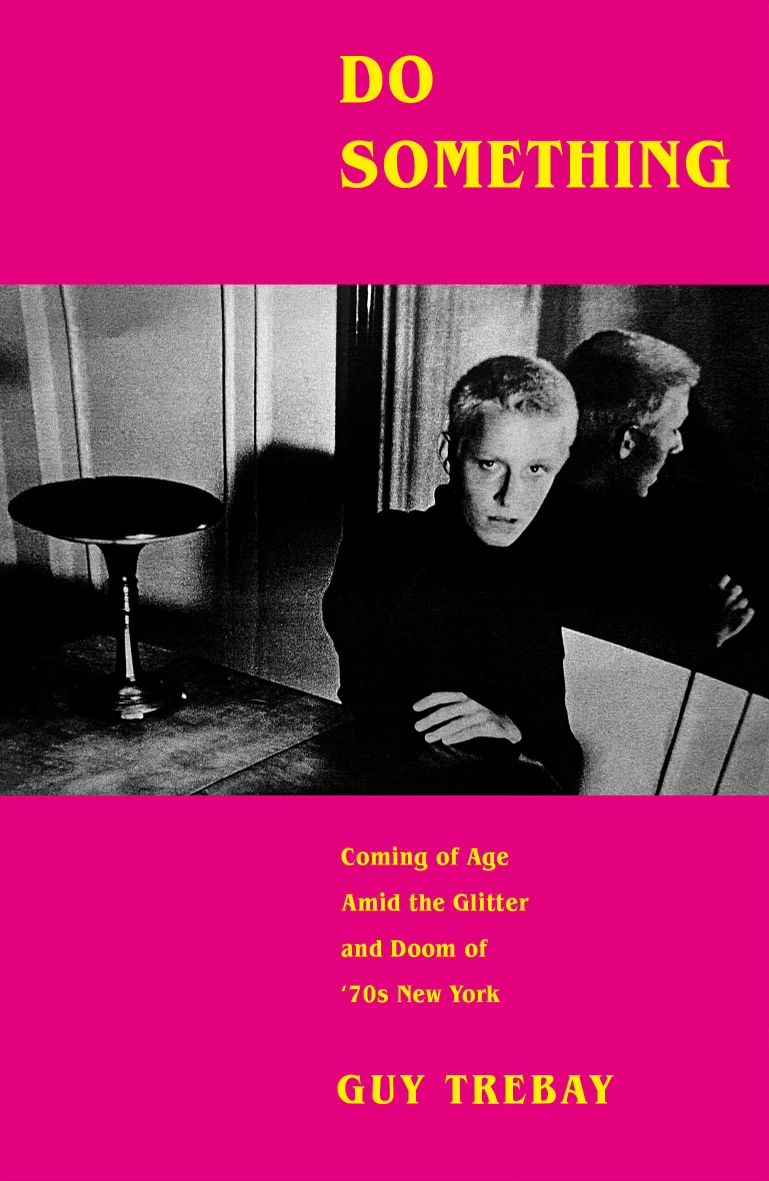

At the beginning of his memoir Do Something: Coming of Age Amid the Glitter and Doom of ‘70s New York, Guy Trebay is digging through the wreckage of his family home that has recently burnt down.

Trebay, who is 22 years old at the time, is out on Long Island trying to find a suitcase of photos that his recently deceased mother had kept. When he does stumble upon it, he then goes through a complicated process to restore the images in his tiny apartment on Carnegie Hill. This sequence of scenes will serve as a synecdoche for the book, where the author not only uncovers the traumatic and scandalous events of his upbringing but brings them back to life with his extraordinary prose and attention to detail.

Although the memoir begins with his chaotic family and everything that was lost, Do Something is much more about Trebay’s self-education among the drag queens, artists, and writers, who were all trying to invent themselves and escape the confines of normal society during the 1970s in New York. In the book, Trebay effortlessly drifts through scenes with Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis, Jamaica Kincaid, and Charles James as well as through his exposition of his self-discovery and becoming a writer at The Village Voice. Today, Trebay is The New York Times’ fashion and style writer, and we spoke about escaping familial binds, the workings of memory, and why experimentation has died.

SHANE ANDERSON: Towards the end of the book, you suggest that the stories you’ve patched together “could have easily been imagined.” This passage seemed quite revealing since the narrative is very detailed and reads more like fiction than the simple recounting of events in a memoir. Where did these elaborate details come from? And could you speak about the interplay between fiction and memoir?

GUY TREBAY: Well, there’s that old joke that novels are memoirs and memoirs are novels. And it’s funny because, when I showed the book to a friend who is a non-fiction writer of memoirs, she asked how I had done the research. Initially, I was surprised by that. I thought that it was my life and this isn’t something I have to research. I had never kept notes or a diary and so this book was not drawn from existing documents. It was largely a memory project and I happen to be blessed with a very robust memory. It’s a feature of my journalism too. I did of course do a lot of research, but that was after finishing the first draft.

I think perhaps this question comes up because Do Something has something of the structural quality of a work of fiction. And I like the idea that the book is not so much a document of me as an individual as a larger story. Narrative propulsion was the most important element to me.

SA: This is very apparent. And it fascinated me that you moved from one point in time to another, from one person to another, with such ease.

GT: I wanted the story to work the way memory works. I didn’t want the linearity of “this happened and then another thing happened” because I think, for most of us, consciousnesses migrate between periods in our lives at any given moment. This happens to be my natural way of writing, but I don’t think it’s in any sense unique to me. One influence on how it came together might be that I have a fairly demanding day job and I didn’t take any leaves of absence or a year off to write it. I used all my vacation time and weekends, leaving the project and then revisiting it. This may be why the original draft was twice as long as the book ended up being.

SA: Really?

GT: I think that’s fairly usual. When I started the book, I thought, “This is my life, how challenging can it be? I’ve been a writer for a very long time, I’ve got this.” In reality, the process was incredibly humbling because there were many new skills to acquire, things you don’t use in journalism.

SA: To return to your day job, I was surprised to see that the book has very little to do with fashion. Was this because you only started writing about style and fashion for The New York Times after the period you depicted?

GT: My aim was always to stop the book in 1990. Because 1990 was a great rupture. It was the year of the greatest number of AIDS deaths in New York City, for instance. I didn’t come to The Times until 2000. And although I was hired at The Times to write about fashion, I’ve covered many other subjects. Prior to coming to the paper, I’d written almost exclusively about urban life. I was writing for The New Yorker and other magazines before and had been at The Village Voice for 20 odd years. In my column there, I periodically wrote about fashion, but it was more in a phenomenological way. It was not criticism.

SA: Do Something feels very phenomenological to me, it’s focused on your experience of events rather than on the events themselves. And, as mentioned, the pictures you paint are very rich. The attention to language and depth of emotion felt Nabokovian to me. Was he an influence?

GT: It’s very flattering to be called Nabokovian but he has not been a key writer for me. I didn’t go to college, barely finished high school, so I lack the foundation blocks or even the touchstones of a more formal education. That might be a plus in a way because I had no preconceptions of what constituted the canon. I’ve been quite magpie in the way I’ve filled my head and educated myself and truthfully, I wouldn’t have had it any other way.

I know that writers always pretend they don’t look at other people’s work, but there are some books by writers, mostly contemporaries, that accompanied me wherever I went to write. When I got stuck I would dip into André Aciman’s Alibis, Gabrielle Hamilton’s Blood, Bones & Butter, Michael Ondaatje’s Running in the Family, or an early Alexandra Fuller book, somewhat in the way a cabinet maker might look at another craftsperson’s dovetail. Sort of: “How did they do that?” David Hockney used to take binoculars to museums to examine Manet’s brush strokes.

It can be crippling: Joan Didion is a writer you don’t want along for the ride, because her Hemingway cadences can be like a drug. I never thought of it as in any way imitative. People have this idea that writing is produced from some pure sphere or that it flows through you courtesy of the muse. I think of it a lot more pragmatically.

SA: There’s this idea of the “self-made man,” of someone who “makes it” through their own efforts and not through money, education, or social status. One could say that this is true of you and the way you moved upward. At the same time, I think there’s this belief that this is no longer possible. Nowadays, it seems like you need a master’s degree before you can even apply for an internship. Do you think it was easier to do such when you were coming of age or was your story also an anomaly at the time?

GT: I was an anomaly then. I had grown up substantially in very fortunate, upper-middle class circumstances. Certainly most of the kids I knew were tracked for conventional lives: great SAT scores, Ivy League college, marriage, and family. But there was this parade of calamities in our lives that upended everything. That is pretty much the substance of the book. I mean, my father lost his business to an embezzling business partner and my mother died suddenly at age 42. Our family house burnt down and one of my sisters committed a federal crime, was arrested and then bailed out—by me—before forfeiting bond and disappearing underground for over 20 years. It was obvious I was not going to have a lot of support and so my instinct was to protect myself and get away. In that sense, New York at the time was a perfect refuge.

Keep in mind that this was a radically different time. I attended the 50th anniversary of The Voice a few years back and at the party I bumped into Ed Fancher, one of its founders. He was in his 90s at that point and when I spoke to him, I mentioned how miraculous it was that I was given this opportunity, considering I had no credentials of any sort. He said—these are not his exact words, which are in the book—“Oh, we never wanted to hire anyone with a journalism degree.’’ Now, of course, you need an advanced degree to apply for an internship.

SA: Did you ever have imposter syndrome?

GT: Doesn’t everyone? I mean, the thing I try to keep in mind is that it was not my ambition to be a writer. I wasn’t the editor of the high school newspaper. I had not written boyhood essays or anything like that. I started out with the wish to be a painter, a fine artist, and I was talented at it. But then—it isn’t correct to say I fell into writing as a career, but when the opportunity presented itself, I soon saw that it’s what I was best at doing.

SA: Do Something is a fascinating chronicle of young people discovering their identity and playing with it. Many of the protagonists change their names and their genders, most famously Candy Darling. Since so many of your peers were drag queens and early proponents of a performative theory of gender, did you ever do the same?

GT: I know it doesn’t seem very radical today, but if you look at the image of me on the cover—with this bleached platinum blonde crewcut—that was by no means a usual look in 1972. But I was not experimenting with gender. It was more a matter of trying on different identities to see which fit.

SA: In the book, everyone seems to be wanting to get away or to be somebody else. It seems applicable to you since you left home at an early age. But at some point, you write that you were “determined, in my unformed way, to be nobody but myself in a world that, as someone once said, day and night does its best to make you into everybody else.”

GT: That’s the job of a life, right? That sentence has more to do with a kind of self-examination that I wouldn’t be able to undertake until later in my life, but it seems to me that everybody I refer to in the book and everybody I knew was experimenting. It’s an American story, the story of transformation. It seems sad to me now that—even with all the supposed plurality—that people are pressured to commit to an identity. That is inconsistent with human nature. At the time I’m writing about, there was this tacit understanding that identity is fluid and mutable.

One of the premises of the book is that a lot of the experimentation of the time was a product of real estate. In New York during that period, artists including Jackie Curtis, Candy Darling, or Holly Woodlawn could afford to patch a life together without the pressure of conventional careers. I don’t think Candy ever had a fixed address. She couch surfed. But Jackie had this great loft on Second Avenue that was later taken over by Peter Hujar and, let’s be realistic, how would someone as chaotic—and protean—as Jackie have paid current New York rents.

Artists have been pushed so far out to the margins that sometimes I think, “Next stop Portugal.” Once you’ve moved to the Rockaways, you might as well keep going. That isn’t to say that plenty of young artists won’t find a way. But it cannot be the same when the average rent for a studio apartment is something like $3500 a month. That may be why New York City feels substantially drained of a kind of street energy. In the pre-digital age, you had to go out to get news. You had to go to clubs. You had to check the wheat pastings to see who was playing where. Information traveled tribally and within certain areas. Things were happening in the Lower East Side and not on Park Avenue because that is where rents were cheap.

One of the things that is almost never remarked on is that 100,000 New Yorkers died during the AIDS pandemic. That’s a lot of real estate to return to the rent rolls.

SA: It’s easy to be nostalgic about previous times and I certainly have that with Berlin. I know you’re not a Nabokov disciple but what would you say about that quote from Speak, Memory, where he says, “One is always at home in one’s past”?

GT: Well, I’ll probably be damned for saying this, but that Nabokov quote is a crock. It doesn’t make such sense to me. The thing about it is: what is the past? A quote I prefer is the one from Borges you’ll find in the book. He asks whether we actually remember the past or rather the last time we remembered it? It is certainly true, and one of the key things I took away from this process, that if I sat down to start this book again today, it would be a completely different animal. Not just structurally, based on things I’ve learned, but the remembering itself would take a different form.

SA: Do you mean your remembering changed?

GT: These events did occur. This is not a fictitious book. But the memories they conjured would not be the same. If you think about it, does anybody ever tell the same story in exactly the same way twice? Maybe liars do.

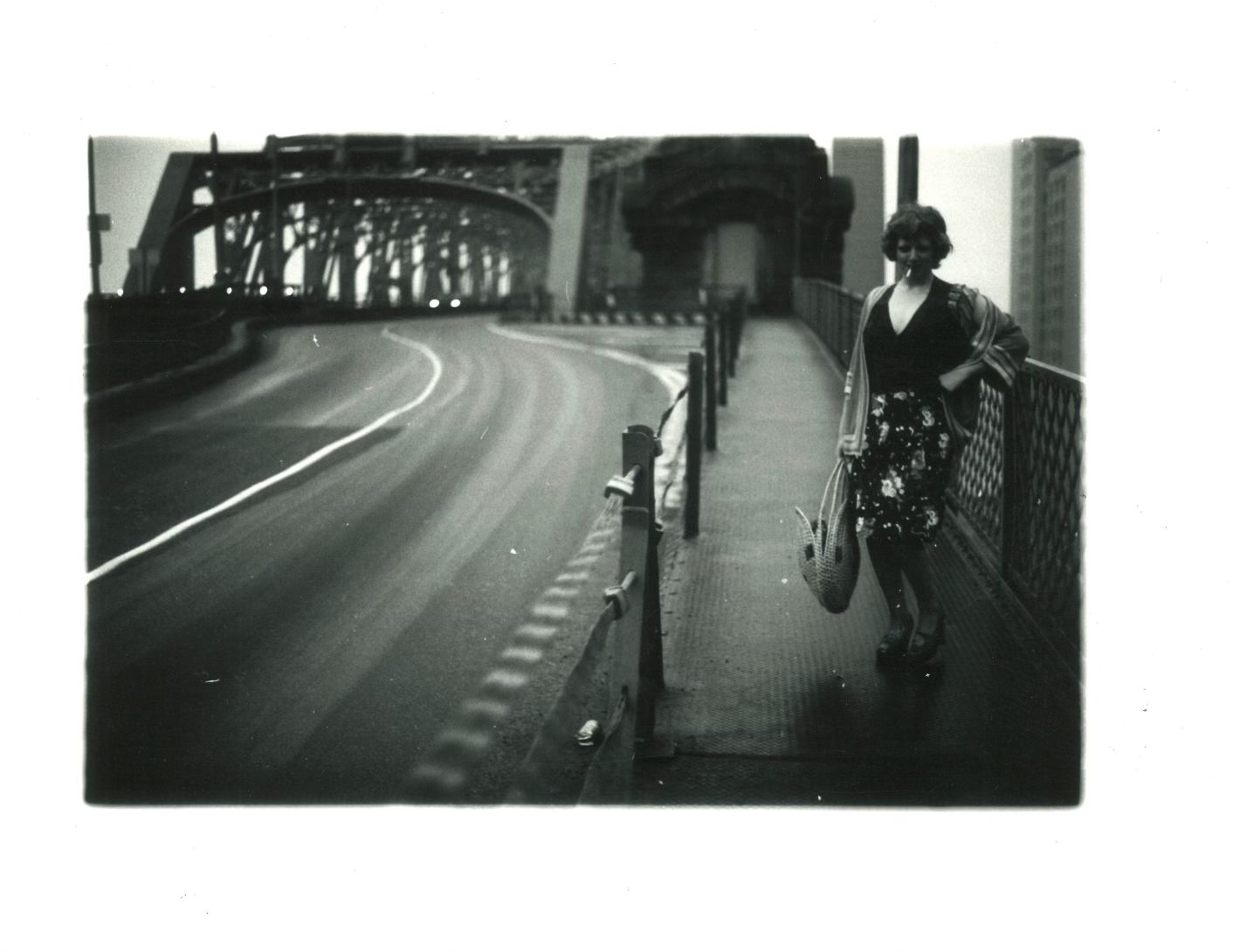

Here’s an example: 20 or more years ago, I was traveling in India and barreling around New Delhi with the novelist Gary Indiana and the Hungarian-American photographer Sylvia Plachy. We all had exactly the same day, did the exact same things, and at the end of the day had seemingly been on completely different adventures. While I have a diagrammatic nature and was sort of parsing everything I saw for logic, Gary was novelizing, and Sylvia had formed an impressionistic inner slide show.

Similarly, if you talk to any of my remaining siblings, they would have different renditions of our family life. I think that’s probably true in every family.

SA: You dedicated the book to them. How do they feel about the story you’ve presented?

GT: I’m pretty much only in communication with my brother and we are very close. He’s been hugely supportive. I will say that when I was working on the book, there were many concerning things to consider when you’re writing about the lives of other people who don’t have any control of what you’re going to say. And working on this, it was important for me that I didn’t create more harm. There had been enough damage. Like most writers, there are these moments in the writing where you try to settle scores and get the story to go your way. But when I approached it again, I realized it doesn’t benefit me and certainly not the reader to use writing to settle scores. I turned to my friend Jon Robin Baitz at one point where I was trying to solve a problem, deal with a difficult situation from the past, and he said, “Be light with it.’’ That was the solution. I could record these things with more distance, be honest and reportorial about my own experience and in turn the material became lighter. I could feel more globally forgiving—of myself and of others. It’s not a book written to correct, instruct, or justify. It was written out of the need to consolidate my own feelings about what had happened and to bring myself into a resolved and compassionate present.

SA: Has that worked?

GT: Yeah, it has.

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON