Behind the scenes takes center stage in CAM HICKS’ book debut: For the Porch

|Octavia Bürgel

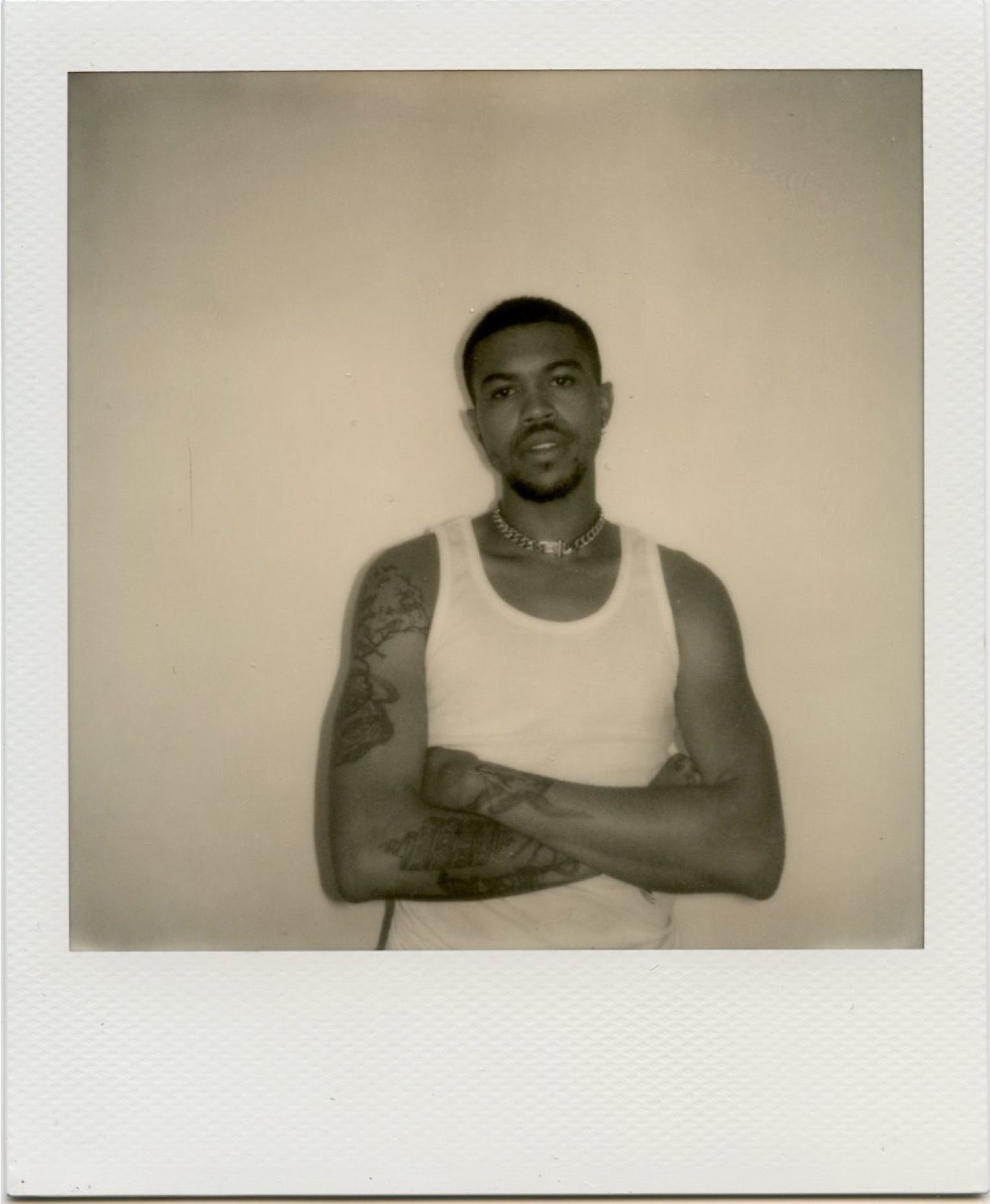

Before he picked up a camera, before he founded the blog that would earn Virgil Abloh’s attention and launch his career – Cam Hicks was a D.C. kid with an eye for style.

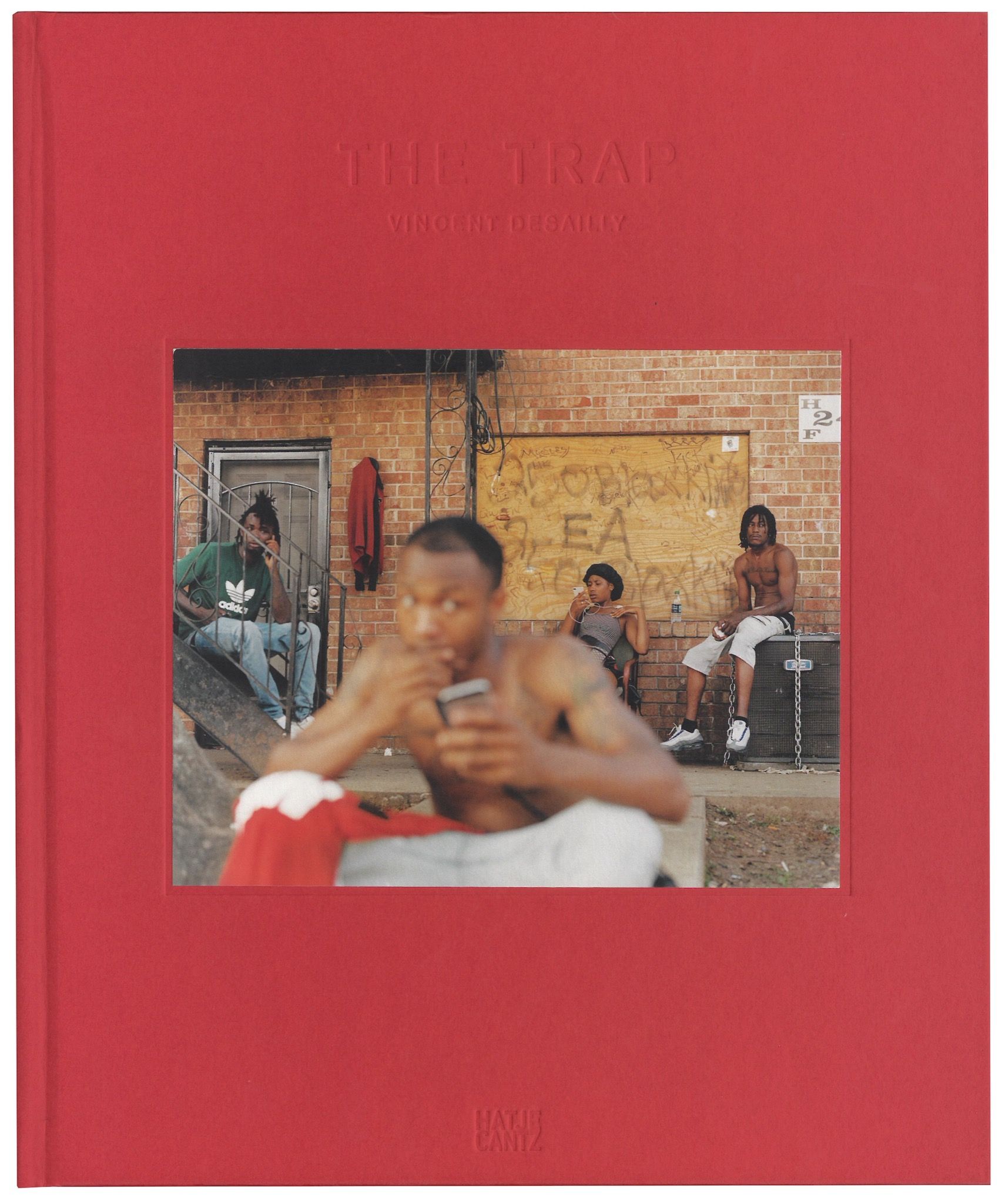

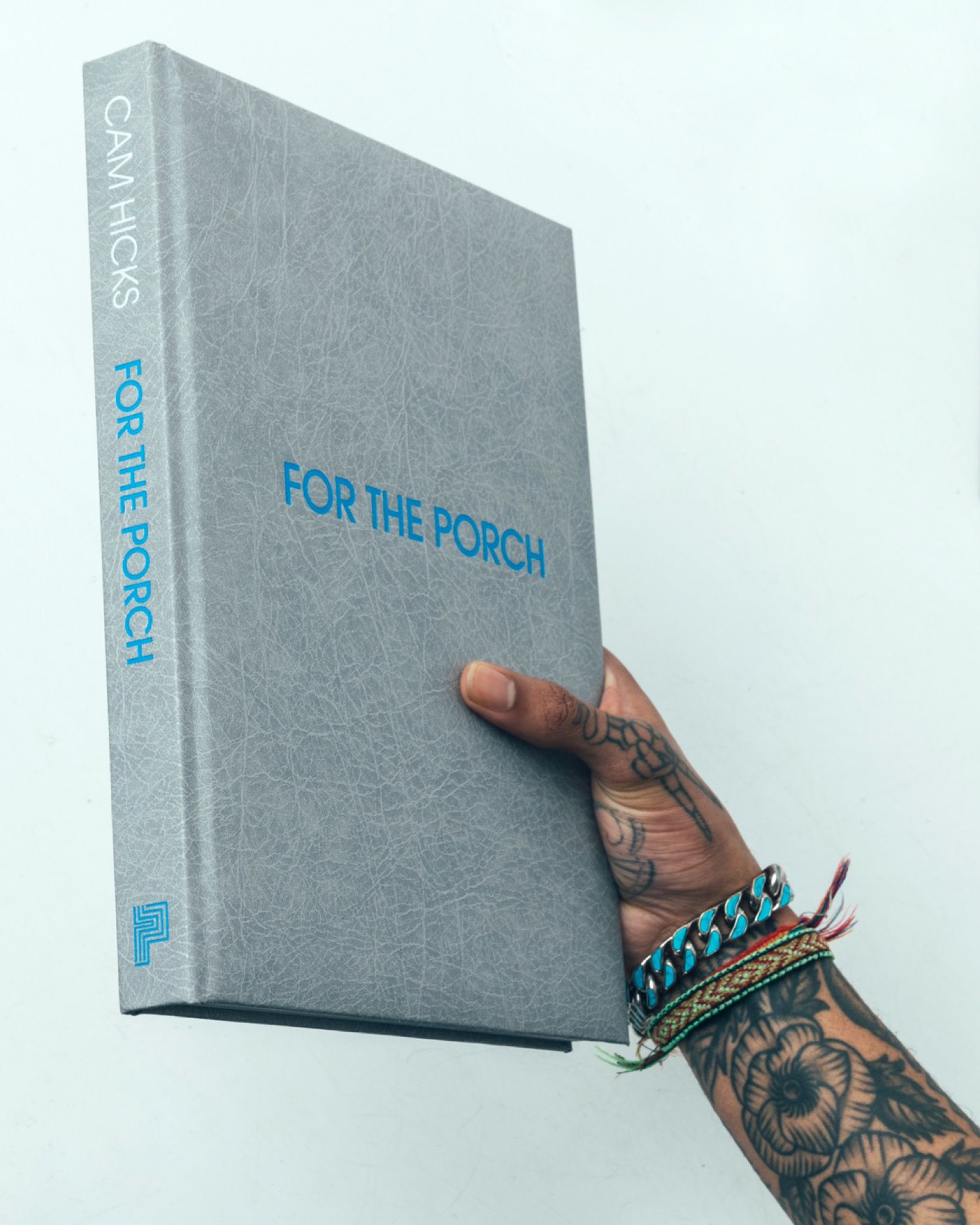

“I love working in fashion, I love design, I love clothes – it’s been a thing for me forever, since going to department stores with my mom as a kid,” the New York based photographer and emergent creative director tells me over Facetime. Origin stories such as this one mean a great deal to the 28-year-old, whose debut book, For the Porch, will be released next week. Originally scheduled to launch with a signing at Manhattan’s Dover Street Market in late March, Hicks’ plans – like infinite others – were delayed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. After a few weeks of cautious monitoring, Hicks has decided to forge ahead with two rounds of social-distancing approved web drops: a limited number of signed editions will become available on the DSM U.S. online shop on May 5th, followed by a general release through Paradigm Publishing on May 6th.

Combining archival materials with recent photographs and diaristic text, For the Porch narrates the arc of Hicks’ early career. Writing of his parents in the book’s opening pages, he says, “For a while, I thought they wanted me to mirror exactly what they did. Get a diploma, a good paying job, you know the rest.” He graduated from college with a degree in IT, and quickly landed a job at an IT company near home. But it did not take long for the job’s lack of creative opportunity to leach his motivation. Hicks had always stayed up to date with the worlds of fashion and photography and had been complaining for months about the lack of innovation in those fields, when a friend finally challenged him to do something about it. Thus The Upsetter was born. The platform became the playground for Hicks’ first experiments with photography and styling, reinstating his imaginative drive. He began producing editorial content for whichever brands would respond to his requests, and it was not long after that he decided to move to New York to pursue his passion for real.

Though the book makes use of Hicks’ editorial and commissioned work for brands such as Suicoke, Louis Vuitton, and Nike, it is more than just a highlight reel of his recent accomplishments. Fundamentally, it is a window into his view of the world – a contemporary witnessing filtered through the viewfinder, the scanner bed, and the smartphone screen. It is familiar for its use of contemporary visual vernacular, yet novel for its earnestness, sensitivity, and tactility, in a time when social media compresses emotionality into the void. When we met virtually, Hicks spoke candidly about the pressures induced by technology, and setting a good example for his younger peers.

What was the selection and curation process like for the images in your book?

I had a photo show at this store called Nepenthes in midtown that the owner of Paradigm Publishing came to. He told me that the photos were cool, but that the text on the wall had really stuck with him. We kept talking more and more, and finally he asked if I wanted to make a book around the same concept. At first I had so many different thoughts: “My career is just starting, who am I to make a book?” So many people are making books right now – it’s kind of a trend – so I was like, “If I’m going to do this, I have to go all out.” I decided I should get humble real quick, get honest.

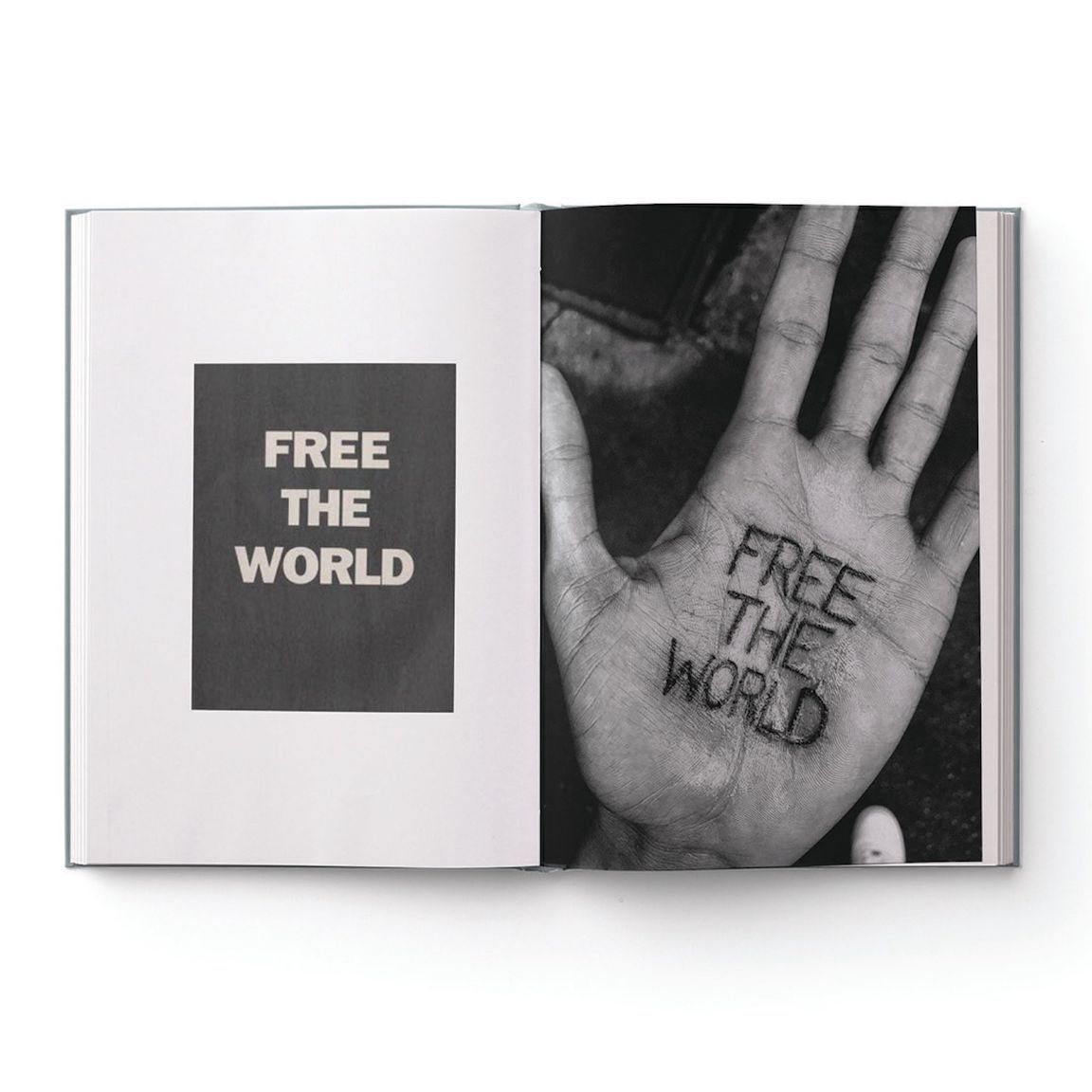

Something that I’ve been battling against is people only showing the glorified aspects of this lifestyle – being a freelance “creative” – and making it seem like this amazing Narnia fantasy world. I feel like it’s directing younger kids in the wrong direction. I realized that if I was going to make a book that my 15-year-old self might see, I wanted to let them know that if they’re feeling low, they’re not alone. I’m blessed to work with Louis Vuitton – but sometimes I’m in my room depressed, worrying about life shit, just like everybody else. It was easy to do the layout and pick the photos, because I had a sense of what I wanted to say. The harder part was making sure that the story flowed, that the copy made sense, and that it was from my voice – while also portraying how much of a roller coaster this is, in a way that was both genuine and cathartic.

Your skepticism of social media-induced “meteoric rises” to prominence definitely comes through in the book. I wondered at times if it was an inherent contradiction to be so critical getting that success early on, while also being in that position yourself. I imagine it might be a point of contention for you – how do you mediate that experience in your personal life?

Before I even got back from my first LV show, I was getting a bunch of messages from people telling me that I was the gatekeeper between the street level and high end, putting all of this unnecessary pressure on me. It got me really in my head, and I had some low points after that because I was like, “How can I keep up with everybody’s standards?” Moving so quickly, I have to make sure that I keep my head down, focus on what’s next and try not to get stuck.

I can admit that for a second, after that first show, I got sort of gassed up in my head, and it took me in the wrong direction. I wasn’t thinking about who I would be in five years or what I was trying to do, I was just like, “well, look – I shot LV.” Once I got out of that mindset things got a lot better. I just stayed in the cave and worked.

The other side of it, for me, is that it seems like my success happened so fast to everybody else – but I was interning for Fader in 2012 for like, $400 a month. At the time I was living with some members of A$AP Mob and meeting tons of people, so when I came back to New York in 2017, I had a network already. I’ve always loved the story of the Tortoise and the Hare, because I’ve been doing shit like this for nine years now – it just takes time for it to hit a pinnacle point like this. I wanted to show that in the book, because it hasn’t been as fast as everybody thinks. I’m not as “up” or living as glamorous a lifestyle as they think. All I can say is I worked, I networked, and I treated it the way I used to treat basketball when I played: I’m not going to let anything get in my way, I’m gonna get it done.

Photography is so complex because it used to be so exclusive and technologically novel, and now it has become one of the most ubiquitous mediums you could think of. We live in an era that everyone acknowledges is particularly oversaturated with images – at a certain point it becomes hard to differentiate between meaningful images, and images that are just imitating a visual style that has been coded with meaningfulness. You mention being called a “gatekeeper” in the past, what is your stance on that position?

When it got down to the nitty gritty of making the book, I deleted all social media because I didn’t want any influence. I didn’t want to think about the gatekeepers or their opinions, I just wanted to focus on my work. It worked for me to not think about them as much. Sure, you know they’re there, but gatekeepers can’t be that forever – everything is changing and breaking down all of the time. As long as you stick to your guns and stay really passionate and patient, that’s all you can do. I have a younger homie, he’s 19, and he’s always like, “I don’t know what I’m gonna do with my life, I need bread, when are things going to work out for me?” and I’m like, “bro, you’re not even 21 yet.” I know that it comes from the speed of Instagram and seeing all of these people looking like they’re killing it all of the time, but you can’t worry about those things.

When I look back on the time that I spent working for Fader, I stayed low even though I was surrounded by people who would be considered the “gatekeepers.” I just wanted to keep working. You just have to keep all of that hierarchical stuff out of your head while you’re trying to make, because if you think with it in mind you are going to try to make your work to those standards. It can cloud what you truly want to do. The work just needs to be good. Don’t do all of the extra gimmicks and it will probably be fine. It might not be this photo, success might not happen this year or the next one – but at some point it’s going to stick if you just stay true.

It’s hard with social media, because you feel like you’re in competition with the whole entire rest of the world. As a result of the pressure of that constant competition, you can’t even afford yourself the opportunity to figure out what your practice is, or develop your questions, or why figure out why you’re engaging with your chosen medium. It bubbles into even more pressure on young artists – photographers in particular, I think – to make every shot the perfect one. There’s no room for play–

Or growth.

Which are the most essential things to any artistic practice, regardless of the medium. You have to put in the time, and you have to get really fucking frustrated with your craft. You have to have low moments both with yourself and with your creative practice to inform why you’re doing it. It’s such a paradox.

When I was just starting out, I was in that Virginia bubble seeing what people in New York were doing. I saw that people were popping off just by branding themselves, and I started trying to emulate that. I realized quickly that it was soulless. I was just making younger kids be even more consumeristic, instead of picking up a craft. If I’m going to be an example to kids I don’t know, how am I actually raising the bar?

It came together with this book, because I learned so much in the process of making it. When I honed in, deleted all social media, and stopped thinking about anything else, I felt like it was the best work I had ever made. It’s truly mine, and it’s not something on Instagram that’s only popping because it’s LV. Sure, that content is in there – but this is from my eyes. I’m barely on socials now because this really showed me that I need to just stick to what I know, and everything will be fine. Even if it’s not, at least it’s me.

“It was like [Virgil] had a door that he wanted to open for me… what he did for me is a standard I hold for myself”

It’s nice to hear a critique of social media from a young person who actually relies on it to a certain degree, because I feel like the main place you hear that is from older generations who don’t really get it, anyway.

When I was a teenager the Internet was just becoming a thing, so there was a lot of time where I didn’t have it. But I grew up with the Internet, so I have some degree of expertise at the same time. I have both perspectives.

I’m 22, and many of my friends are around four years older than me. Instagram came out in late 2010, so a lot of my friends got it when they were going into college – but I was going into High School at that time. I think that those four years of separation fundamentally change how we understand Instagram – and each other, by extension – because so many of our interactions happen through the platform. I do feel like the timeline of what constitutes a “generation” is being condensed in real time, according to new developments in technology.

I’ve been thinking about this too. I put all the stuff that’s on my Instagram into a well-produced book, and now people are like, “Oh shit, damn, you really did all that?” It’s like, “Yeah I did and it’s been on Instagram for like, three years. You just didn’t notice it because it’s been on Instagram, along with everything else.” It makes me want to make more tangible objects, and not even focus on posting things anymore. I’ve gotten more of an opportunity to express myself by making one tangible item than I have with all of my Instagram. I’ve learned so much about how I should be moving in the future.

For the Porch is fundamentally a book about telling stories. The title is very simple but it carries a lot of implied meaning – my childhood best friend and I always joke that even if we both end up married, we hope that our partners die first so that we can retire together in a house with a porch where we can spend our days talking shit. Are there other storytelling practices that you engage in personally as a complement to your photography?

Being from Virginia, growing up in D.C. and Maryland, that concept is so familiar. All the young kids are playing in the grass while the old heads are sitting on the porch, drinking, chilling, and talking about the past. When I get old and I’m sitting with whomever I’m sitting with, I want to be able to look back and say “wow, I did these things, I made these mistakes.” If there are kids around, then I will have stories for them that can hopefully teach or inspire them.

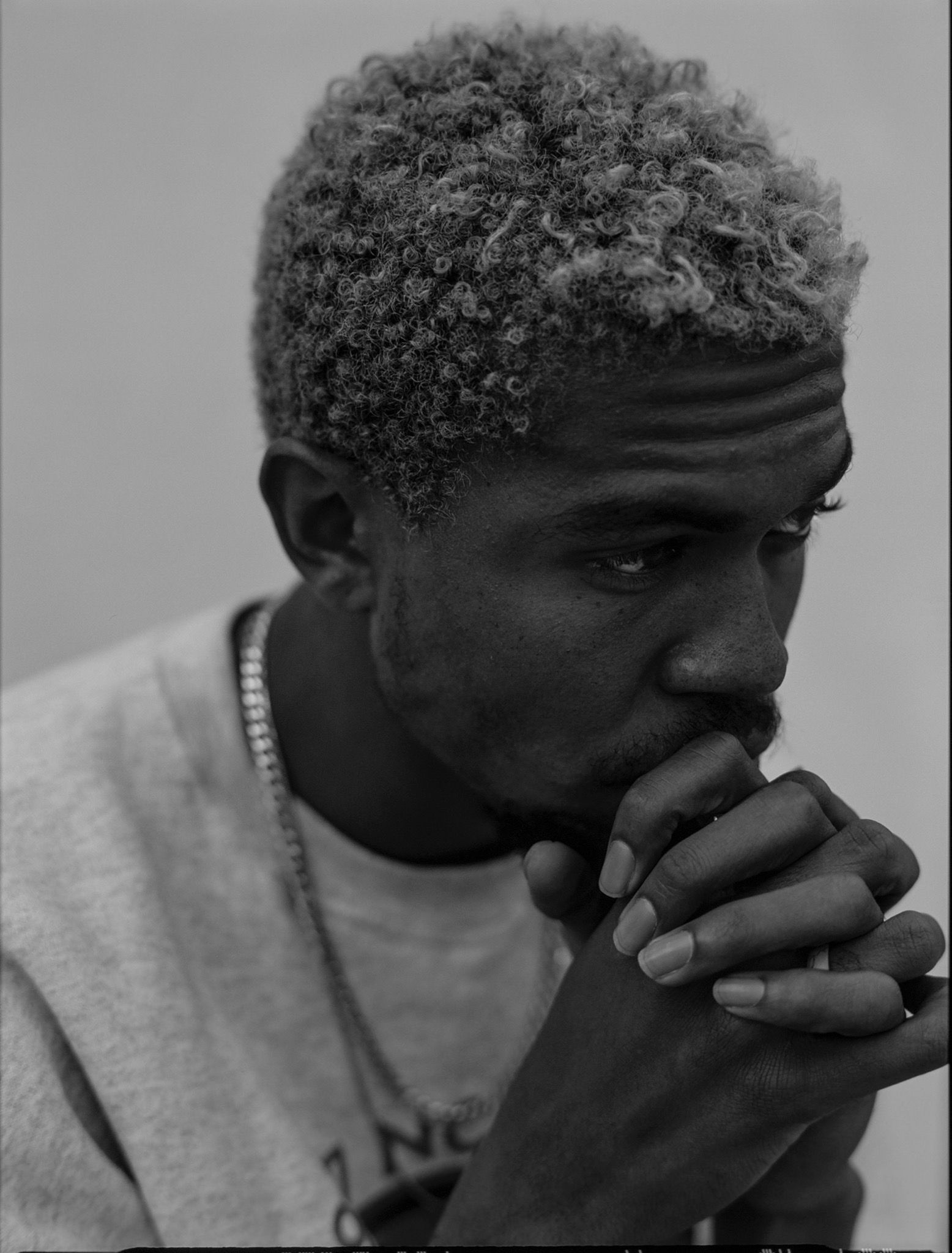

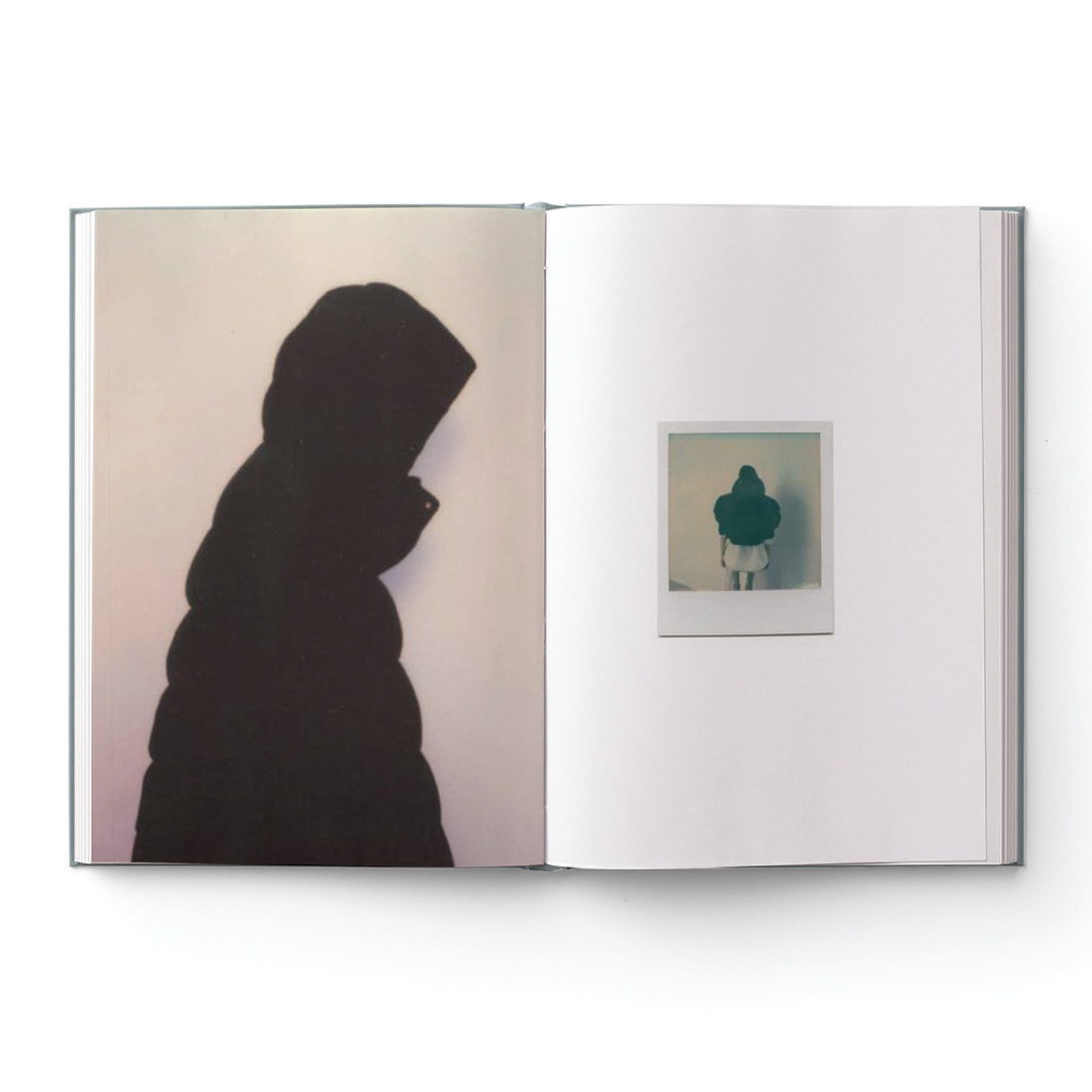

I do a lot of journal writing, because I like the idea of being able to look back and see where I was at different points. That practice helps me come up with ideas and flesh them out better. There have been times when I’ve been really low and I’d write about it, and then look back at the Polaroids I took during that time and they’re really purple and overexposed – all silhouettes and dark imagery. Other times it’s the Summer and I feel good, I’m with my friends, having fun – and the images will come out super orange and bright. Both practices parallel the emotions I’m feeling. If I’m just doing documentary work then sure, I just have to document. But if it’s editorial, then I’m usually giving off whatever energy I’m feeling in the moment.

The book feels very open ended. Even without knowing your age, it feels like it’s part of a narrative that is still in the process of unfolding. With the internet, again, I think there’s a lot of anxiety that stems from feeling like you’re writing your life in stone. Every time you post, it exists out there forever, despite your individually developing taste and interests. It’s nice that your book makes space for the experience of change and evolution. Can you tell me more about what a photograph is to you – an object, a feeling?

It goes in stages for me. First I’ll look at a photo at face value, then at the information it’s trying to relay. I think it’s a product of the way media gets put out in the world now, because if you look back at Irving Penn or creative directors like Paul Rand or George Lois – they were speaking to a lot more information than the average photo does now. When I started learning about George Lois and I saw the cover he did of Muhammad Ali for Esquire, it really haunted me. You see that picture and you understand that Muhammad Ali is more than a boxer – he’s about religion. The photo talks about all of these other things without even saying it. That’s where I want to get with my work.

I realized over time that people weren’t necessarily hitting me up for my photography – not to say that it isn’t good – but there are other things that come along with it. Whether it’s a brand that just wants to have a black photographer shoot for them, or they want access to my Instagram followers – people have a lot of ulterior motives outside of just a good photo. I want to get to a point where somebody hits me up with a proposal and I can spend a month trying to craft just that one photo that speaks to more than “hey, buy this suit.” Every social media is a marketplace now. It’s the main thing that they do, and I don’t want to just make people buy things that they don’t necessarily need. Sure, it’s cool to have clothes and objects and stuff, but at a certain point there has got to be more than that. Maybe I am selling a suit – but what’s the story? Who is in the suit? What am I trying to talk about? What current issues am I trying to address?

Those thoughts have been in my head now more than ever because of this book. I know it is going to give me more of a voice, and I need to be ready to use that voice in the right way. I have to hold myself to the standard of whatever I said in the book, I can’t backtrack. I can’t tell kids, “don’t just be a walking billboard, work on your craft, be patient, and make really good work” and then one week later be like, “go buy these shoes.” But I like the challenge, and I think it’s going to make my work better.

In the last few years, we have seen a lot of publications celebrating this new era in black image making. Personally, I’m not convinced it’s a good idea to canonize developments on the spot, but we are certainly in an unprecedented moment. Are there peers or contemporaries of yours whose work you are particularly inspired by?

Since my end goal is creative direction, I don’t think I look at photographers in that way – though there are really great photographers out there. I think Rennell [Medrano] is great, and I love Micaiah Carter’s work.

I’ve always felt divided on this, because I love the fact that there are tangible items – books and publications – that celebrate what black people are doing on a whole. But I think it’s more important for individual black people to be the example on their own. If you’re making a publication on a specific subject and you’re highlighting specific people, it’s impossible to include everyone. There is no way to tap in and catch every person, so it ends up reinforcing that hierarchy and exclusivity thing, which is really not the point at the end of the day. The point, in my opinion, is to be a good example to younger versions of me as best as I can. The message isn’t to do it like me – do it like you – but you can do it.

I hit up Virgil as a younger black creative, and he didn’t ask any questions. It was like he had a door that he wanted to open for me. A lot of people say that he doesn’t do enough, but you have to understand that he doesn’t own LVMH. He’s a creative director, not a CEO. He can’t walk in and say “Fire all of the white people!” It’s baby steps, and you have to let things happen in time. But what he did for me is a standard I hold for myself. Any information, any experience that I got – I want everybody younger than me who wants it to have.

I have a younger homie named Aijani Payne, I think he’s going to be one of the best black photographers in the next three or four years. Every time he comes to me, I’m an open door. If I have a project and I need a PA, I bring him on. I brought him on a Highsnobiety shoot, the next month he was shooting for them. I love that. I tell him all the time that in four years I want him to be better than me, because I know that he can be.

When we first started talking, you made a face when you said the word “culture.” I’m curious to know more about that.

I don’t hate it, but it’s overused in a way where people don’t even really stand behind it. So many people love saying “For the culture!” but it’s like, this Tweet is not for the culture, man. You’re using it too lightly. It’s almost like saying “I swear to God.” If you’re gonna say it, you should mean it. If it’s about the “culture,” then it really should be.

I know the stigma that comes with it too, it’s in the same category as “clout.” They’ve always been words – but now everybody says them to the point where I don’t even want to hear it anymore. I mean, I’ll still use “culture,” but I want to use it when it’s necessary instead of just throwing it around wherever.

I feel the same about the word “creative,” which is so annoying, because sometimes I’m just trying to use the word in its intended meaning. But all of these words have been overused to the point of being incredibly vague and diluted in intent.

I appreciate that you mention the word “creative,” because I remember as Instagram grew and more people wanted to start brands – without having work or accolades or anything – you could look in their bio and it’d say “creative director.” If they took the time to look at actual creative directors to figure out what the term really means, they’d see that none of those people are doing hands-on work. There are people designing T-shirts and calling themselves a “creative director.” It’s like, no – you just had an idea. That’s a concept, but you still need to build it into a brand, and build the brand up in order to be a creative director. You’re not there yet – which isn’t a bad thing – but you put yourself in a box with all of this stigma around you by saying you’re a creative director when you’ve made three T-shirts. It shies people away from you when you could actually have some good ideas, you just branded yourself too early.

Credits

- Interview: Octavia Bürgel