The Politics of Beauty: Tyler Mitchell

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

Do we need to see images that explicitly show brutality, violence, and death in order to process human disasters? Do we need to be visually exposed to death in order to process its causes?

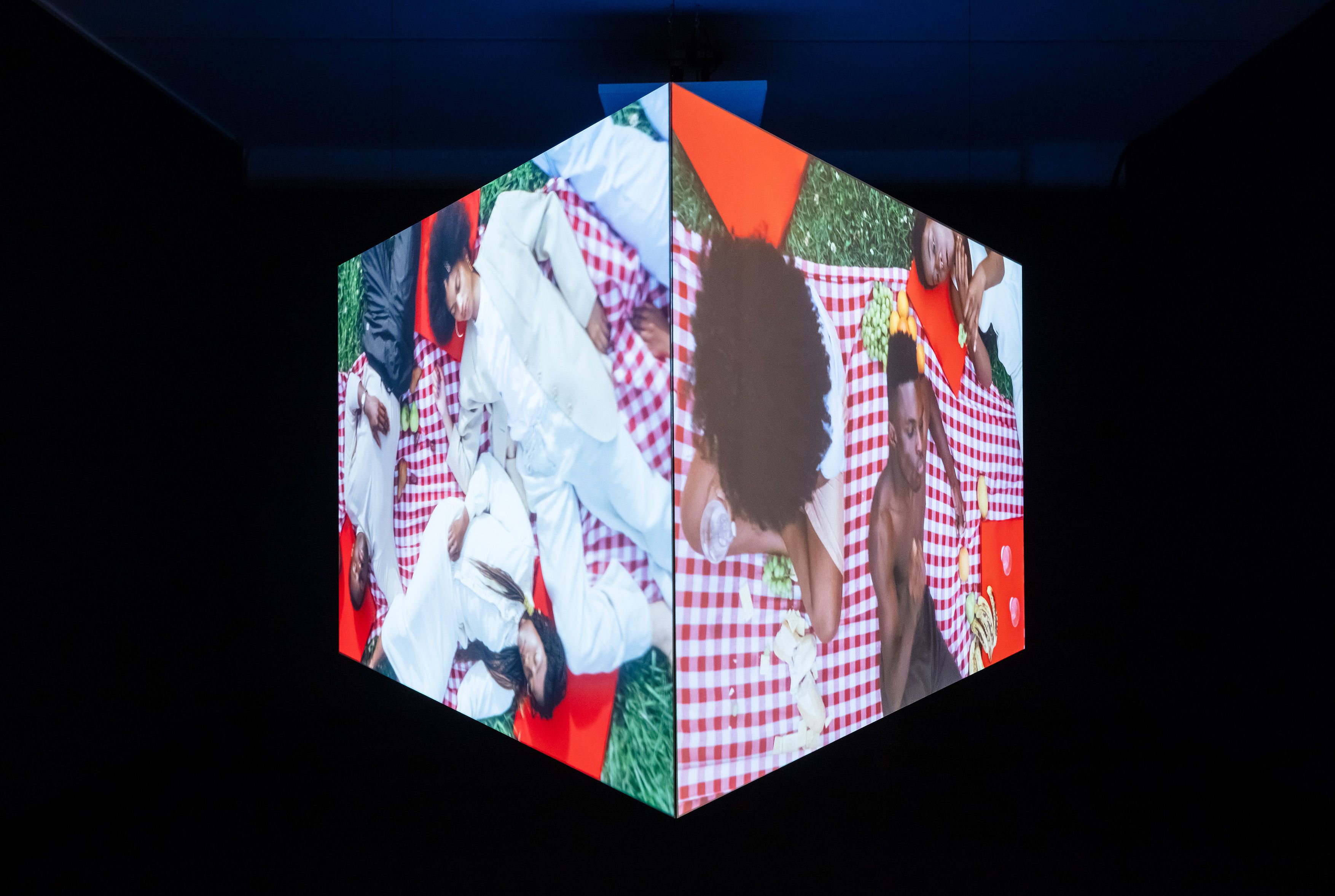

Image-making that is focused purely on “aesthetics,” that is “beautiful,” or that needs to fit the feed is being questioned more than ever. The question of whether you can still produce work that is unabashedly beautiful is one that artist and photographer Tyler Mitchell is also concerned with. Mitchell’s first solo exhibition in Germany, “Wish This Was Real” at C/O Berlin, looks at notions of utopia and beauty while reflecting on artists of the past and suggesting that utopia is not a matter of some perfect future but of a humanist-focused approach to reality. In this interview, he talks to Claire Koron Elat about beautiful images that are still permeated with criticality, racially segregated cities, and the misrepresentation of Black people in fashion imagery.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: Your show revolves around themes including beauty, style, and utopia in the context of Black life and culture. How are these different realms intertwined for you?

TYLER MITCHELL: It’s a hard question to answer succinctly, but I think that I can speak from personal experience about beauty and style as it relates to photography. It all came together through my various interests, being a young Black person growing up in Atlanta, and very much feeling the history of that place. The city is a beautiful mecca of Black culture, but also has a deep history of trauma and segregation.

When I became interested in fashion photography, I was also asking myself what “fashion photography” really is and who it’s for. It felt like an interesting arena to contribute my voice. When I moved to New York to study, I interned at an agency. There, I realized that a lot of the images that we encounter on a daily basis in the world—advertisements, billboards—were being made by a very small, elite group of people, predominantly white men. This is something that the art world and the fashion world has been reckoning with since. So that was the impetus. My work has evolved in other directions now, but as a young person, that’s how I started thinking about how these things come together. How could I, as a photographer, make images of my peers that are a bit less censorious and glamorized in a traditional way? How could I make something that is more reflective of real life.

CKE: Can you explain the segregation that you felt when growing up?

TM: Atlanta is still a segregated city in a lot of ways. Although it’s not segregated legally, there are areas in which predominantly Black people live together. And there are areas in which predominantly white people live together. What’s interesting is that the core of the city is predominantly Black. I think in a lot of other American cities, there’s the reverse happening, where Black people are being pushed to the outskirts because of rising rent and cost of living, which is a huge conversation now. I’m excited to be showing work that thinks about these things—although not in an overt way. But these living conditions informed my upbringing and, therefore, the way that I make my work.

CKE: You said that you started fashion photography out of a certain absence, because there was a missing representation of Black people in photography. Do you feel like that’s still the case? And has your perspective changed now that you’re more embedded in the industry?

TM: It has changed. I would be lying if I said it hasn’t. It’s been a beautiful thing on a lot of levels, because I think the entire world has had these conversations. So much of our community is very focused on this idea of reckoning with and reshaping and expanding histories. What’s been amazing, from my vantage point as a young person and as someone coming to these ideas as a student at NYU around 2015–16, is that there have been people having these conversations long before.

It’s nice that it’s coming back around in a new way. I always lean on the fact that I’m not necessarily doing something new but maybe having an older conversation in a new context. When I got to NYU, I had my mentor and teacher, Deborah Willis. She’s sort of the godmother of Black photography, connecting dots and networking as an artist in her own right. She knew many people, such as Carrie Mae Weems and others in my show. She was a writer doing early work on Black photographers making images of Black figures in their own image. These things were happening in the mid–1900s and even way back in the 1800s. As a student, I was discovering all of that, and I was interested in having that conversation in my own way. How to be indebted to those people, but how to take it to a new place. I do think the conversation has evolved in a beautiful way. It’s become quite a mainstream preoccupation: How do we deal with the ways that Black folks show up in this art historical canon and author their own stories. I think that’s a good thing, and sustained engagement needs to continue.

CKE: Do you think that there are still forms of misrepresenting Black people in fashion imagery or in visuals in general?

It would be interesting to get to a place where we stop looking at things as the right or wrong way to photograph a Black person and instead understand the nuances of how images operate in the world. How does an image move a viewer on a visceral level?

I often talk to Arthur Jafa, who has become a friend, about this. He always says, “I don’t do the uplift thing.” Which I take to mean he’s not interested in uplifting Black life in a conventional way; he’s more focused on readdressing history directly. He’s interested in the darker side of how we’ve been treated in the past and often rethinks or recasts those events. There’s no right or wrong way when it comes to representational photography. What I’m trying to do is make my own contribution. I hope to speak about young Black life through the mediums of fashion photography, art photography, and filmmaking. Those are the conventions that I play with.

CKE: We live in a world where there’s so much political turmoil, horrendous catastrophes, and human disasters happening. Just thinking about utopia feels almost cynical. Can you still explain what utopian thinking is for you and how it reflects in your work?

TM: There’s a great book by Jayna Brown published in 2021 called Black Utopias: Speculative Life and the Music of Other Worlds. She explores the concept of utopia as a way of imagining alternative states of being and living within Black culture. Brown examines the lives and works of specific figures such as Sojourner Truth, Rebecca Cox Jackson, Alice Coltrane, Sun Ra, and speculative fiction writers including Samuel Delany and Octavia Butler. She investigates how they moved through the world, connected with other Black individuals, and used their music and communal practices as frameworks to explore what utopia means. Utopia is a term that represents an unreachable, perfect society.

Now, I’m not naively stating that some utopia will be reached through my art. Rather, I’m using the concept of utopia as a construct to think about what it has meant for artists in the past. Historically, utopian scenes were often depicted by white European men, painting leisure scenes for high society in Europe. My work questions who these ideas have served historically, who they can serve now, and what they actually mean today. This isn’t about assuming utopia is reachable, but about questioning the construct and exploring its implications.

While questioning this, I’m also in dialogue with Jayna Brown and other Black thinkers who imagine their own versions of utopia. These imagined utopias are not about perfection but are achieved through deep, humanist-focused community building.

CKE: Do you feel like it’s maybe about fulfilling some sort of Black desire that has been neglected?

TM: Perhaps. Fulfilling desire, that’s an exciting term. I like that.

CKE: Your images are obviously very beautiful if you just look at them, but still highly political and engaged with a social, economic, and political past. How does this blatant beauty and criticality coexist for you?

TM: The two always coexist, especially in today’s world. I love this quote by Miuccia Prada, where she’s says, “What you wear is how you present yourself to the world, especially today, when human contacts are so quick. Fashion is instant language.” These questions of what is considered beautiful, what’s considered not beautiful, what’s considered desirable, and what’s considered not desirable are at the center of our politics as humans.

Especially in 2024, the idea of making unabashedly beautiful work becomes one that people question. They wonder, why would you want to make beautiful work? I’ve taken up interpreting and wanting to iterate on the ideas of the romantic and the pastoral in a very direct way, and to not shy away from those things, not only because I like them aesthetically, but because I find them interesting. It’s as simple as that. I don’t know if I’m answering your question, but what I’m saying is that beauty and political concerns are not to be separated. For me, they are meant to be intertwined, and they are intertwined in our society in ways that we subconsciously separate.

CKE: Are these political questions as present for you when you’re shooting a campaign as when you’re shooting an editorial or making art?

TM: My practice as an artist has always been about an overall vision regardless of medium. I’ve really leaned into campaign making, editorial making, museum and gallery show making, altogether as much as I can. I think there have been people who have done that very well. I think about Wolfgang Tillmans or Viviane Sassen. So absolutely, when I’m shooting a campaign or when I’m shooting a magazine editorial, I find that to be an exciting arena to have these conversations in the same way I do in a museum or gallery show. My practice has never been to separate those things. It’s always been to integrate them.

CKE: You’ve also said a couple times in past interviews that you don’t want to appeal to an art audience. But then you had a show with Gagosian.

TM: I guess my feelings on that have changed! It’s interesting because I said that at a time when I didn’t really know the landscape of fine art, because I wasn’t exposed to it. That world hadn’t welcomed me with open arms. It wasn’t an audience or a community that I felt I was a part of. For example, I didn’t go to Yale and get an MFA in fine art, which, in America, was the standard track to becoming an artist who’s taken seriously in that world at one point. So those things felt very far away from me. When I said that I’m not necessarily addressing a fine art audience, what I was getting at was that I wanted the scope of my work to be much broader. Photography had broader ambitions when it was invented, and my photography has broader ambitions in that way now.

Of course, by showing in museums, it’s a bit naive to say I’m not addressing a fine art audience because I am. In that way, my thinking has evolved and changed as I’ve grown older, and now I don’t necessarily agree with what I said there. What I do think still holds the spirit of what I was saying is that photography has so many applications and uses in today’s world, whether it’s a selfie uploaded by a family to an Instagram page, all the way to “fine art” at the “highest level.” I like the idea that photography can exist on all those planes and doesn’t need to exist in any one context. It can be in an editorial and still be meaningful, it can be on Instagram and still be meaningful, and it can be in a campaign, a billboard, a website, or at a bus stop, and still stop a viewer and make them think.

CKE: Would you say that the art world is more judgmental than the fashion industry?

TM: Each context has its own particularities, and what I’m trying to do is move seamlessly between them and chart a new path because it excites me. I get as excited to see my work on a printed page as I do when I see it in a gallery or museum context. The two serve very different purposes and engage in distinct conversations. They each have their own specificities, and for me, it’s not so much about judgment.

When I first started showing my work in galleries, I experienced imposter syndrome about crossing over, if you will, from creating images for magazines and brands to exhibiting my work in a museum context. That’s societal programming, almost like cultural conditioning, suggesting that there would be judgment placed upon me. Once it was over, I felt empowered to continue doing more.

I have been fortunate to have my work sustained and engaged with in both arenas—art and fashion. I believe that great photography should elicit the same response.

CKE: I think it’s interesting when photographers who start in a more commercial or fashion context transition into an art context, starting to exhibit physically or maybe even turn to other mediums. Does it have to do with some sort of desire to go beyond commerce?

TM: It’s been kickstarted more by having conversations with other artists, seeing the way they present their works, and being inspired by them. A big watershed moment for me was when Deana Lawson came to my studio, looked at my work, and sent me an essay entirely about materiality and photography, emphasizing how the actual content of the image is just as important as the photograph being a tactile object.

As a young person, I often experienced images digitally. I talk a lot about my first exposure to creative imagery being on Tumblr while growing up. Certainly a lot of younger people exclusively experience images online, and that has become the dominant mode, which was the mode that I grew up with.

It was only as I grew up and interacted with other artists that I began to consider the idea of an object or sculpture as an interesting way to tell a story intertwined with photography. That photography isn’t divorced from its materiality as an object, but actually the two heighten the experience together. That’s why I’m encouraging other young people to go and see my shows, and go see other shows in general, because that is a different experience than seeing something online. I think that it’s part of growing up, and part of being like, “what else can I do, what else is possible?” And that excites me.

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT