An Andy Warhol Foundation Grant That Clearly Wasn’t Enough

|Estelle Hoy

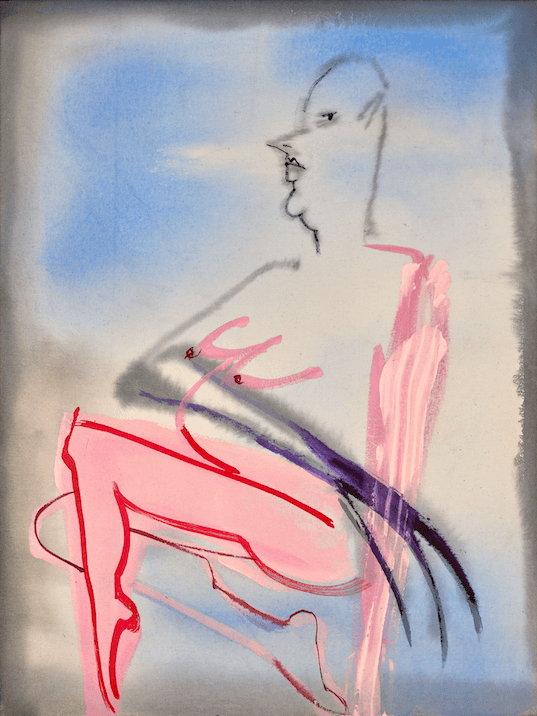

Camille Henrot and Estelle Hoy dialogue in the exhibition “Jus d’Orange“ at ICA Milan, in which their respective works intertwine with each other in a visual and textual narrative. Curated by Chiara Nuzzi, the exhibition will open end of September. “An Andy Warhol Foundation Grant That Clearly Wasn't Enough“ and “In the Kitchen with Roland Barthes,“ written by Estelle Hoy, are two chapters from the book that will accompany the exhibition, receiving exclusive pre-publication with us.

An Andy Warhol Foundation Grant That Clearly Wasn’t Enough

Getting an annulment is just a minor setback.

My never-husband-to-be was a badly behaved know-it-all on an Andy Warhol Foundation Grant that paid for the cheap bouquet of frangipanis from Ode à la Rose on 28th and Broadway. Fake plumeria are more Odor à la Nose, just quietly, but what is to be done about futile problems of class?

Besides, I’m not a man of “acting out,” my madness is tempered, and I love doing things I hate—I’m Catholic, after all.

I exhaust myself deliberating about irritable nothings of substance and do my best to slip into the threat of choosing not to choose, or if I absolutely must choose, I choose the unbearable. The reasonable sentiment of what can or cannot proceed is preceded by the antiquated notion of getting up ten times out of nine.

I choose nine times out of ten.

Once the exaltation of marriage had collapsed, the exaltation of breathy abnegation began, and we found fulfillment in the conviction that everything works out, but nothing lasts. To our advantage, the Warhol Grant covered the bodega tab in full with enough left over for a Daruma doll from Dollar Plus; this could last only so long.

I was courageous to put an end to it. I suffer without adjustment.

In the Kitchen With Roland Barthes

Roland Barthes—a man of the cloth—reminded me that some things are simply unviable, and all annulments can be substituted with art. I tend to believe people.

My now never-husband was older than Giorgio Agamben, or at least looked it. Agamben was mindless but had perfect theories about mindlessness we could occasionally learn from; his work was a series of lone philosophical blunders that showed him to be a very careless boy. The war against intelligence has a long and torrid history, which I’ll forgive, considering Agamben himself argued for the state of exception. I’m living proof of what mercy can do.

I left the bodega with my Daruma Doll and caught the J-train to the Whitney Museum of American Art to read Barthes on hard museum banks and escape a history that never existed. The Meatpacking District is a clever neighborhood substituting unrevivable nullification of animal flesh with Jackson Pollock’s urinary tract infection, which is about the same as art, so again, Barthes was right.

Museum-goers looked at me swaddled in lapses of intelligibility and an eggplant tux as old as Barthes himself, wondering if I too was an artwork they should “discover.” Mercurial eyes and open-gaped mouths calling for proof that the howls of conversion disorder could manifest just about everywhere.

Half a century later, the semiotics of eggplant uncertainty drew dilettantish, ill-bred crowds like the scene of a crime.

Credits

- Text: Estelle Hoy

Related Content

Why Is Desire Always Linked to Crime? KARL HOLMQVIST

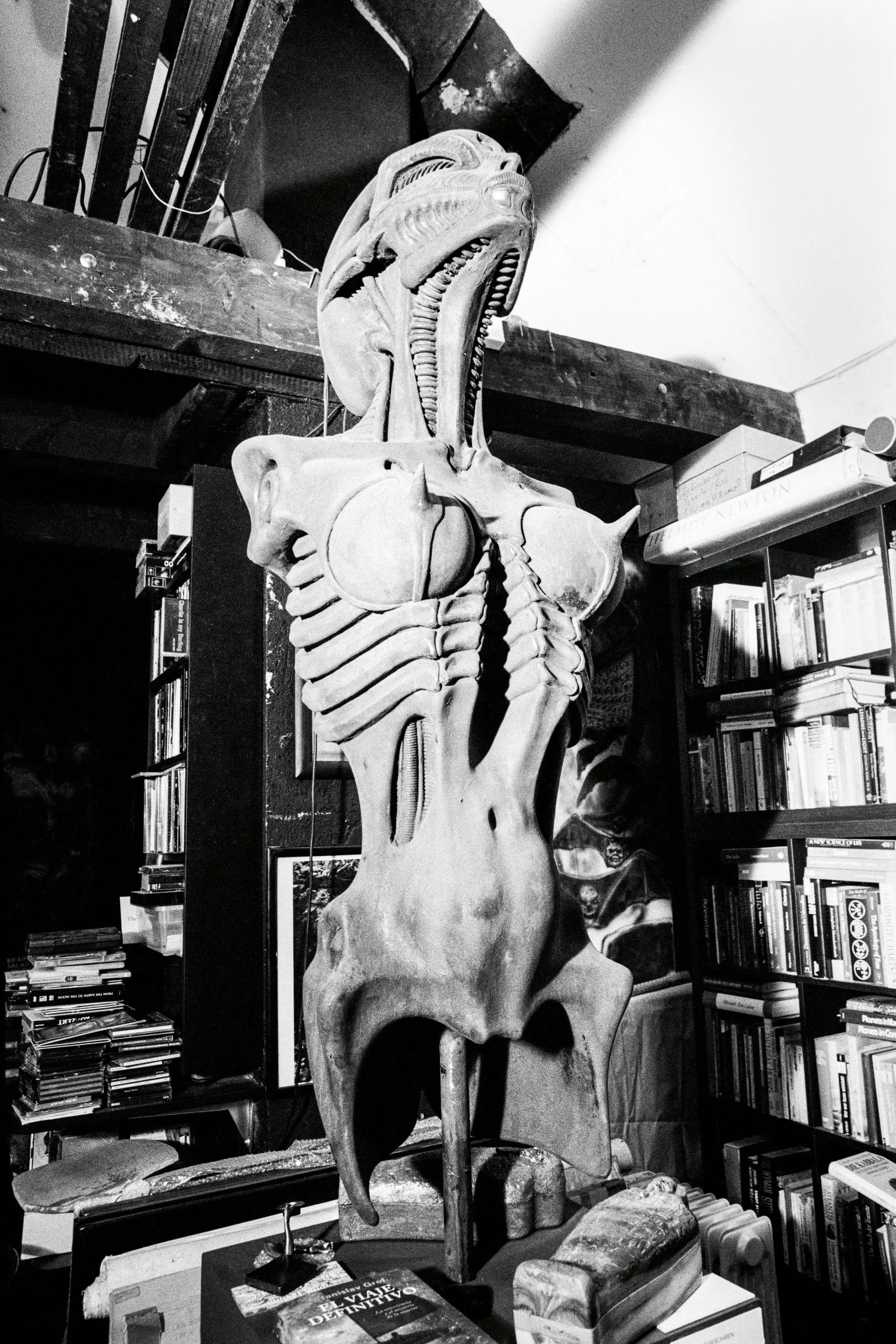

Libidinal Teratology: HR GIGER by CAMILLE VIVIER

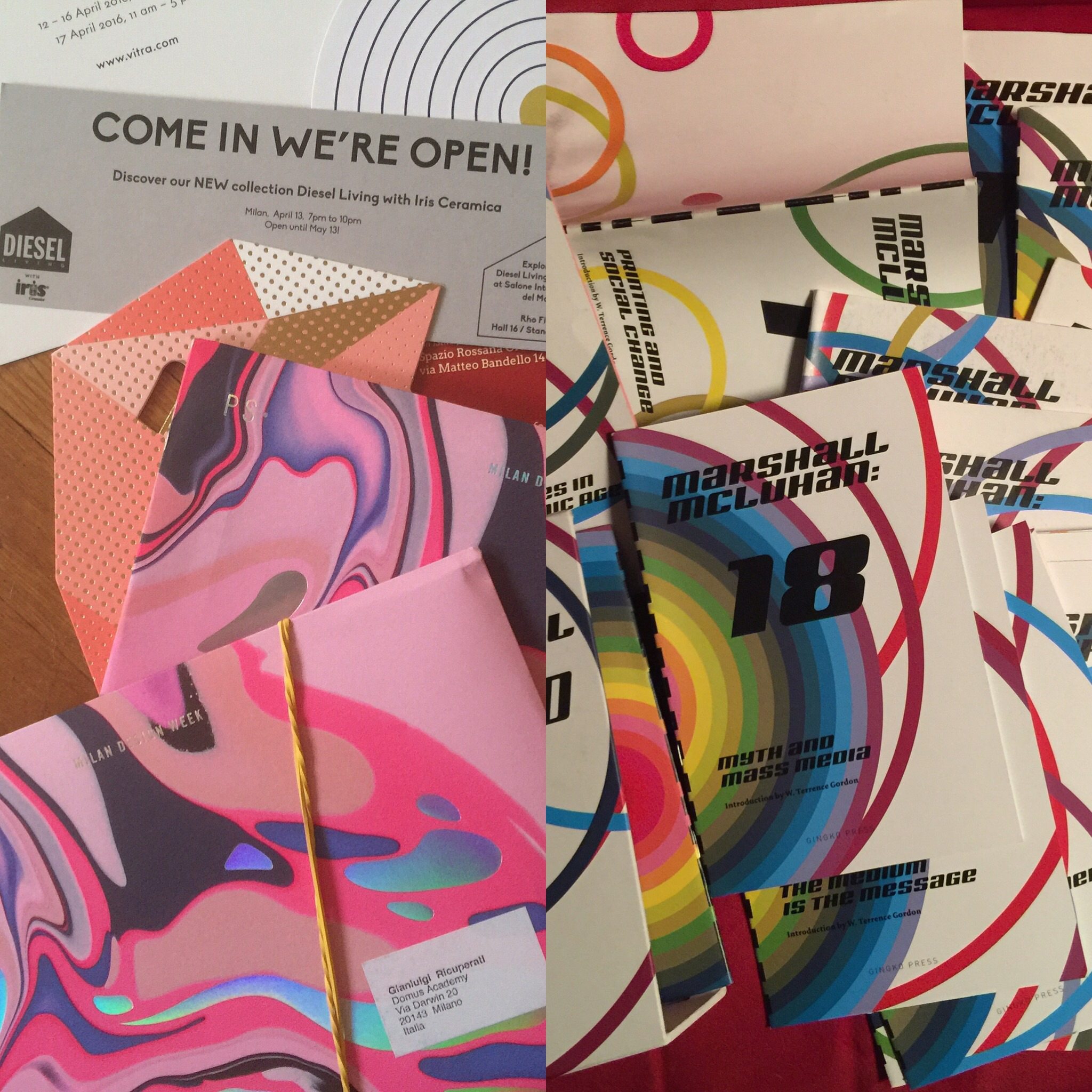

Visiting Milan design week 2016 with MARSHALL MCLUHAN

From Sex-Tech to Global Warming: The Chronicle of 17 Artists Who Created BMW’s Acceleration Aesthetics

Ciao, Milano: Billboard Takeover Rebrands the Post-COVID City

032c Issue #43 “CULTURE CRISIS. Therapies for the confused” Summer 2023

The Real Thing: Exhibiting the Art of the Bootleg

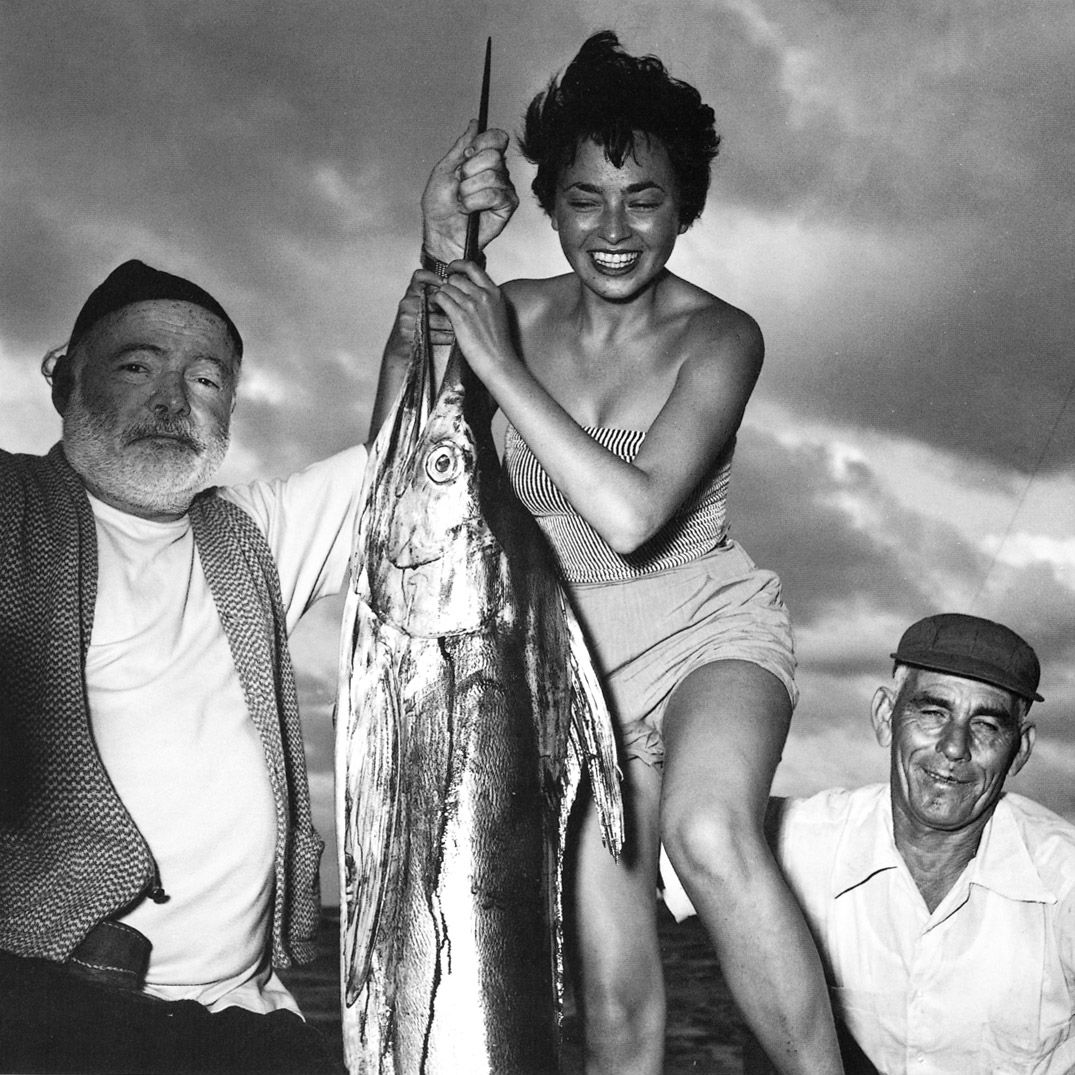

INGE FELTRINELLI Tried to Take Over the World with Photography