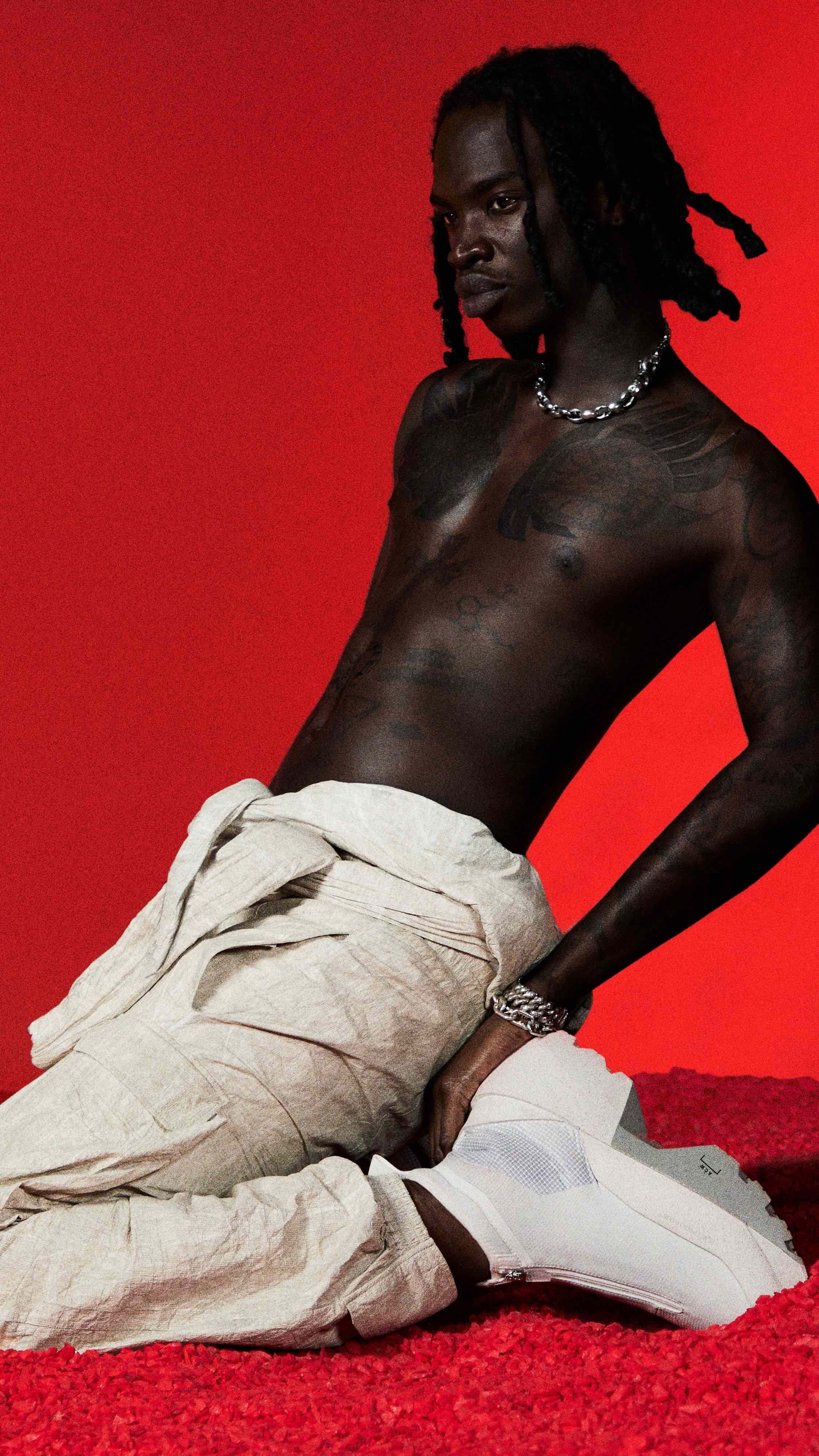

LANCEY FOUX: Purple Reign

|Cassidy George

When the enigmatic British rapper LANCEY FOUX drops a new album, the buildup and excitement are reminiscent of that created by a best-selling fantasy author. In late October, Lancey handed over the next stage in his musical saga to his voracious listeners. The 22-track sonic narrative, titled Life in Hell, is set in a world of far-out samples, layered with lyrical twists and turns, and filled with emotional cliffhangers. On release day, Foux invited fans in New York to physically experience the world of the album. Concertgoers were invited to a repurposed synagogue on the Lower East Side outfitted with a labyrinth, where papers with Foux’s hand-written lyrics scattered the floor and demonic dancers patrolled the halls. Lancey took the stage as the sovereign demon, with his skin painted lilac and his irises an unnatural, icy blue. Pointed, prosthetic ears peaked out from his braids as he commanded a sea of jumping people. When Lancey and the crowd chanted his chorus, “I set the world on fire,” the entire building appeared to shake.

Since he began releasing music in 2015, Lancey has remained a somewhat confounding entity to those who find comfort in categorization. The East Londoner was raised in the world of grime during its 2000s renaissance. Although the stylings of grime season his flow, and the scene’s biggest stars are among his inner circle, Lancey is not a grime artist. Many on the other side of the Atlantic have placed him under the buzzy new umbrella of “rage rap,” alongside the other rising superstars of America’s next gen underground, like Yeat. Streaming platforms have dubbed his recent record “hyper rap,” but Lancey believes that any known musical terminology will paint an incomplete portrait.

Perhaps the only metric that can be used to measure Lancey’s output is an unorthodox one: his use of color. Like Picasso's respective Rose and Blue Periods, Lancey's artistic development can also be traced by dominant hues. The rosy shades that characterized his Pink and Pink II years have evolved into vibrant violets since he began working on Life in Hell in 2020. With his painted skin, Lancey quite literally embodies purple – the color of kings and clergy – on stage. But in speaking with him after his New York show, it was clear that he also embodies the essence of purple in spirit.

Despite the explosiveness of his music, Lancey is calm, collected, and reflective in conversation. He speaks with the assurance of the known ruler of his own reality and radiates the harmony of someone who abides by his own decree. While Lancey’s breakout record Friend or Foux was inspired by The Art of War, Lancey has since shifted his literary focus from Chinese military tactics to Roman pragmatism. “I was thinking about Stoicism a lot,” Lancey said of the Life in Hell chapter over a video call. The guiding principle of Stoicism is likely familiar to those who haven’t dipped their toes into Hellenistic philosophy, as the secular basis of a widely known prayer: “Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things that I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.” Lancey – who is unfazed by the chaos of the industry and internet – is an artist who knows the difference.

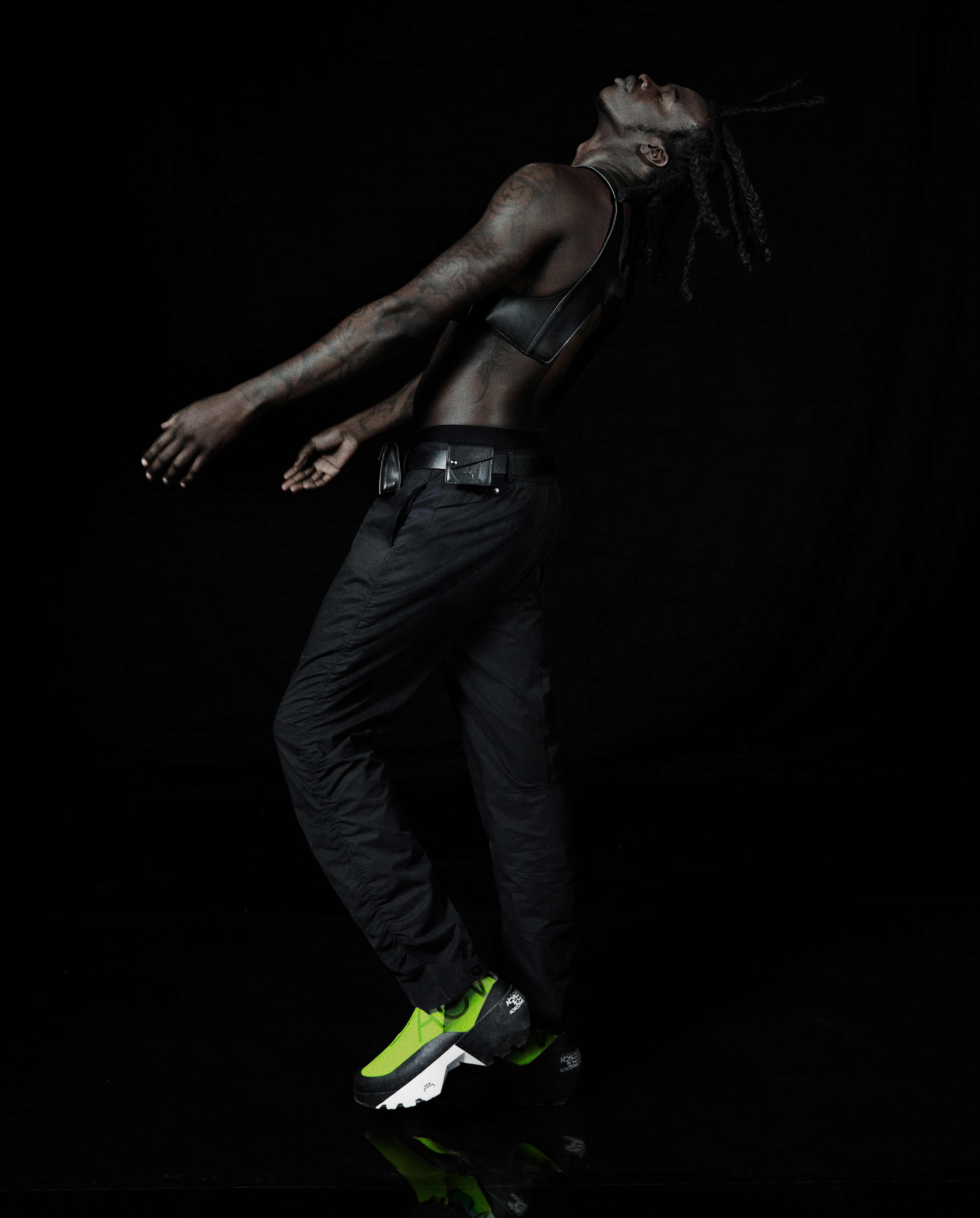

The impact Lancey is making in the music world has also rippled into the fashion landscape, where Lancey’s presence and influence is ever-increasing. This weekend, he begins the UK-leg of his tour, where he will debut Converse and A-COLD-WALL*’s new Geo Forma shoe – which is the latest in a series of collaborations with the brand. Concertgoers will catch a first glimpse of the unreleased shoe on Lancey’s lilac persona. The Geo Forma is a sci-fi twist on the Chuck 70 silhouette, which has been metamorphosized by designer Samuel Ross’ signature avant-garde hues and future-forward, utility-driven vantage point. In celebration of the shoe and UK tour’s kick-off, 032c spoke with Lancey during a brief window of respite about the fantasy of anonymity and the undervalued “art” of business.

CG: Your first album, Pink, was an acronym for “probably I’ll never know.” Does purple hold a similar coded meaning?

LF: It simply comes down to seeing the music. When I get into a certain vibe or mood and make a song, I see its color. Sometimes it’s metallic silver, and hard and industrial – other times it’s pink, and soft and flowery. When I was making Pink, a lot of what I was doing was combatting my environment at the time. Where I come from has a really strong energy. I was thinking: “What can I do to deflect that?” I couldn’t be black and silver all of the time. I knew my music had to be different — and pink stood out. In 2020, purple started to appear. In everything I was doing and everywhere I was going, I saw purple.

CG: Your dad was a DJ, and your mom was raised in a convent. You recently performed Life in Hell in a synagogue in New York, where these two worlds collided. Are you a creative byproduct of these two opposite influences?

LF: My influence from my parents is more from their personality, I think. Life in Hell doesn’t stem from religion, it’s environmental. This album was very much lived. It’s about wonder. It came from conversations and observations – and really seeing things around me. It’s easy to think you get all of the information you need from your phone, but the best information comes from our own eyes.

CG: Friend or Foux was inspired by The Art of War. Did any books inspire Life in Hell?

LF: It wasn’t one book, really – but I was thinking about Stoicism a lot.

CG: Why?

LF: I was trying to figure out what the correlation is between the people I admire. What connects Jay-Z to Nelson Mandela? They’re both very in control. I can’t imagine either of them punching someone, for example. Where I grew up, that was a normal thing, the idea of a counterattack. As I got older, I realized I don’t want to argue anymore. How can you not argue with someone but still win an argument? Stoicism. By being so calm and at one with yourself that no one can infiltrate.

CG: You’ve mentioned that you were frustrated that “India” was so popular because it’s “an easy song” and not representative of you as an artist. Was this album designed to be challenging?

LF: Yes, for sure. It’s meant to be performed in big places with big speakers, so performing is the final step in accepting the album and making myself proud. But I’m never really satisfied.

CG: Are you a perfectionist?

LF: Yes, but in my own way. If we both drew a square and your square was really straight and there was something off about my square, I might look at my own and think “it’s perfect.” I define it myself, but it’s very hard to reach.

CG: That’s also a pillar of Stoicism right, not being affected by external factors and forces? I’d think that’s a really valuable trait to have as an artist, to refuse to measure your achievements against someone else’s parameters.

LF: Only some think so! [Laughs] It’s also detrimental. For example, I don’t watch anything. People will say, “the biggest artists right now are doing this on TikTok,” but I don’t care. I have a different lens on everything, everything I do is geared towards what I consider success — which is not always everyone else’s definition. Maybe it’s just because I’m getting older, but right now I’m really concerned with what I can do outside.

CG: Outside as in “outside of the box”? Or outside as in nature?

LF: In the physical world. As in, when you step out on the road – what are you going to do today that makes everyone outside shake? Not what you put on the internet.

CG: You withhold a lot online. Is that a strategy to cultivate interest and excitement or can you just not be bothered to play the digital game?

LF: The latter. If I didn’t do music, I wouldn’t have social media. That’s just a fact. I live my life like an experiment – and this is all one big experiment. I don’t really want to show you what I’m doing, but I want you to be excited about this new music. I want to show my art to people. I want to show my vision to people. I want to move with purpose. But showing me, the person, publicly to people who are not asking? I’m not into that.

If I meet someone for the first time, I’m really a listener. I’m more interested in what they’re telling me. As an artist, I feel like we should always be learning from others. If I keep putting myself out there without taking anything in, it’s pointless. I’m not here to show myself off, I’m here to deliver something with meaning.

CG: What’s something about Lance, the person – rather than Lancey, the artist – that you wish they did?

LF: I’d actually rather them not know a thing about Lance – I’d rather them just know the music. I don’t have a problem with people thinking anything about me. If one person thinks I’m completely evil and another thinks I’m loving and great, it’s all the same to me. If I could, I’d be Daft Punk and just make amazing things and not have to give my identity away.

CG: Does that come from a desire for self-protection?

LF: It just comes from knowledge of human behavior. When people believe certain things about you, it changes how they act.

CG: You are often associated with artists who are your friends and collaborators, like Skepta, Ye, and Playboi Carti. Too much so, in my opinion. I’ve always perceived you to be a bit of a lone wolf. Do you identify that way?

LF: On the business end of music, people want to buy into something that’s familiar. Everyone loves to loop me in with artists that they’ve seen me with or that I’ve done a song with because that makes things clearer for people. I never make things clear for people, so I think those associations make it easier for people to digest what I’m doing.

I’m friends with artists because of who they are on a personal level, not for the pictures and videos. With Skepta – that’s gang, that’s fam. But Skep and anyone else who has ever worked with me will tell you I’m my own man. I make music and do everything my own way.

Most new artists believe no one will listen to their album, so they think: “I’ll do a song with this artist and use that buzz for everyone to get familiar with me.” I’m the reverse. I want to stand on my own. When I do my show, no one is coming out. I put out 22-song albums with no features on it that you have to unpick. You can make the links after on your own if you want a better picture. No one is really sitting down and listening to albums anymore. They listen to three songs and say, “He’s this” and “that’s the way it is.” I’m fighting that. I’m telling you what I mean without saying the words.

CG: You’re handing people the shovel and saying, “dig deeper.”

LF: I’ll open the door for you. If you want to go through it, you can. If not, then I can’t help you.

CG: Your birthday is coming up! 27 feels like a significant one, or at least it does to me…

LF: I haven’t thought about my birthday or what it means. I feel like I’ve done this before, actually. Some people grow up, but I sometimes go back in time. I go back and forth between a mature and imaginative state of mind. When I was turning 24, I felt like I was turning 27. Now I’m 27 but turning 25.

CG: Even if it’s not meaningful to you, a birthday is always a meaningful prompt for reflection on the last year. What will define this year for you?

LF: One thing that I've been thinking a lot about, and particularly as I turn 27, is how to keep my artistic integrity intact while becoming a better businessman. I can’t just run around being an artist my whole life, there are a lot of mouths to feed. Projects like this upcoming one with Converse and A-COLD-WALL* are really exciting to me.

I’ll tell you a secret, I used to hate this stuff. I hated everything that had to do with capitalizing on art and had a long phase where I was fighting it. I had to grow to learn that business is an art form. Negotiating a deal is an art form. If I can create music, why can’t I do the same thing in business? I want to gain all of this knowledge from myself and my own experience. I’m interested in what I can do for me, versus what I do for a person or a brand or what they can do for me. I’ve been asking myself: what can the businessman in me do for the artist? What can the artist in me do for the businessman?

There’s a lot more money out here for “smaller artists” than people think there is, or than there used to be. You don’t need 100 million streams to be taken seriously. We all hold value. If anyone is interested in you and cares about what you are doing – whether it’s ten, 100 or 100,000 people – you hold value. The task is to leverage those eyes into getting what you need to make more art. When I talk about business, I’m not talking about getting rich, I’m talking about creative reinvestment. It’s very simple: no artist should be without his tools and unfortunately, those tools are getting really expensive. Getting them doesn’t always have to be a compromise.

CG: I’ve always wondered about the origin story of your name. Why “Foux?”

LF: Foux is similar to “faux,” which means fake – which I thought was sick because this is also my fake name. It’s funny though, people can’t even say it. They’re like, “Fuh? Foo?” I’ve actually been trying to change my name to just “Lancey” for three years now. It’s a really difficult and complicated process because I’ve built everything with this name, but I feel that I’ve outgrown it now.

CG: I guess we are all aspiring to be the one-named wonder in our respective fields. I’ll take note of that from now on, though. No Foux, just Lancey.

LF: People will catch on sooner or later.

The Converse x A-COLD-WALL* Geo Forma will be available beginning on December through A-COLD-WALL* and on Converse.com.

Credits

- Text: Cassidy George

- Photography: Zach Apo Tsang

- Studio: Noir

- Executive Producers: Greg Smith

- : Javier Alejandro

- Producer: Ella Kenny

- Fashion: Nick Royal

- Makeup: Jimmy Owen Jones

- Hair: Ryo Narushima

- DOP: Sam Friend

- Gaffer: Kristof Szentgyorgyvary

Related Content

CAN IT SKATE?: Skateboarding’s History of Cannibalizing the Footwear Market

GAIKA: At What Point Do I Encounter God?

Planet Fitness: Anthropo-Frontierism and the Survival of the Fittest

The Cold and the Beautiful: SAMUEL ROSS Reinforces UK Brutalism with the ACW* x DR. MARTENS 1461 Work Shoe

Indefinite Optimism: A-COLD-WALL*’s SAMUEL ROSS

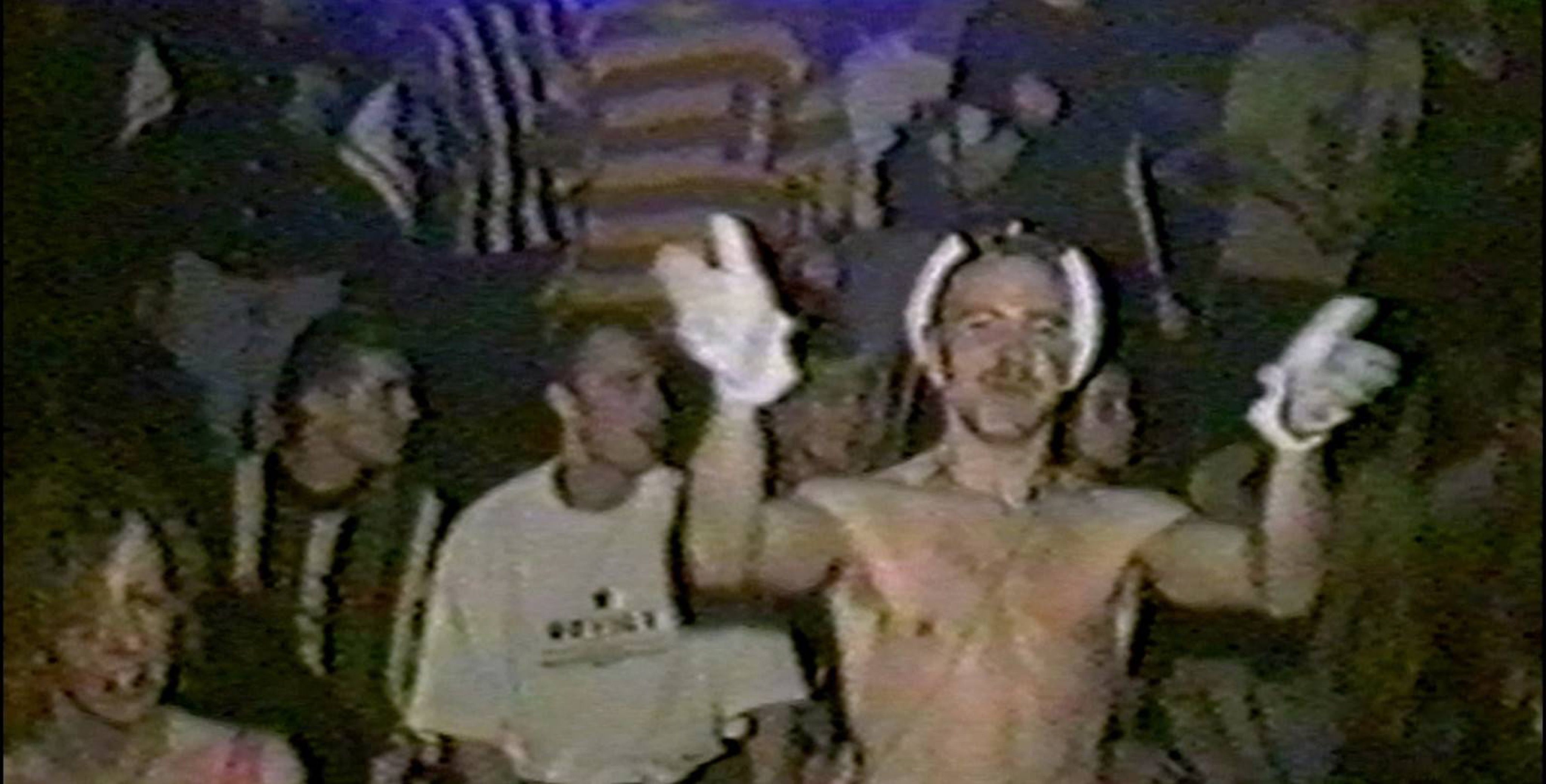

SECOND ACID WINTER: The Roots of Fashion’s Rave Revival

Half a Century of Civilian Sketches from the UK’s UFO Desk

Extremist Footwear: Examining the Spectrum of 2017’s Minimal and Maximal Running Shoes

The Art of Chun-Li: ONITSUKA TIGER meets Street Fighter V

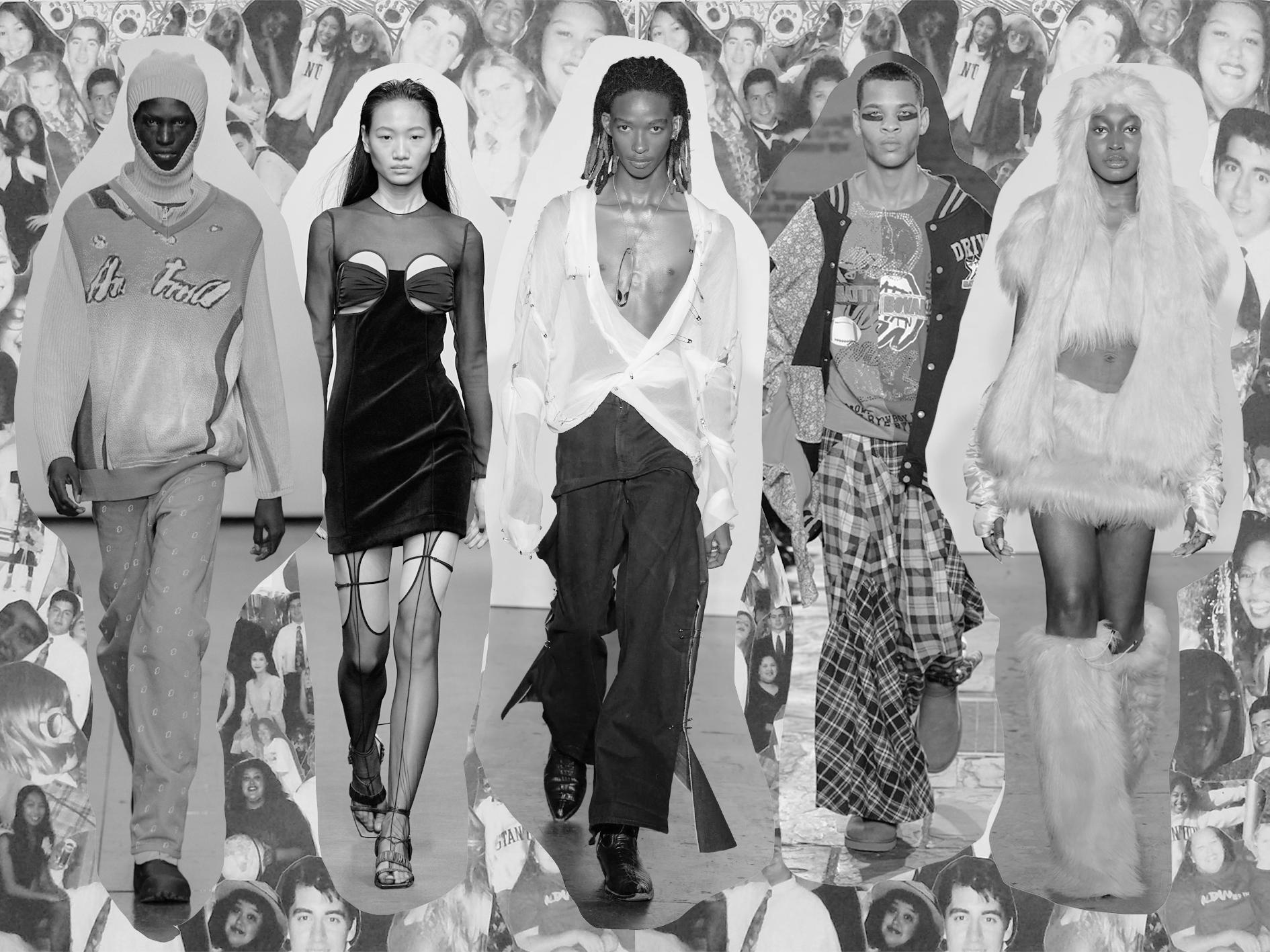

London Fashion Week Yearbook Superlatives: Class of Fall/Winter 2022

Metagaze: SHYGIRL Stares Back