THE PLAYBOI MANSION: A House That Makes Rap Music

|Thom Bettridge

“This is an exclusive look at what happens when a whole bunch of young people get together to mosh … There are elbows … bloody noses … bouncers removing people … This looks like the ultimate, orgasmic expression of what ails us in this culture.” Phil Donahue

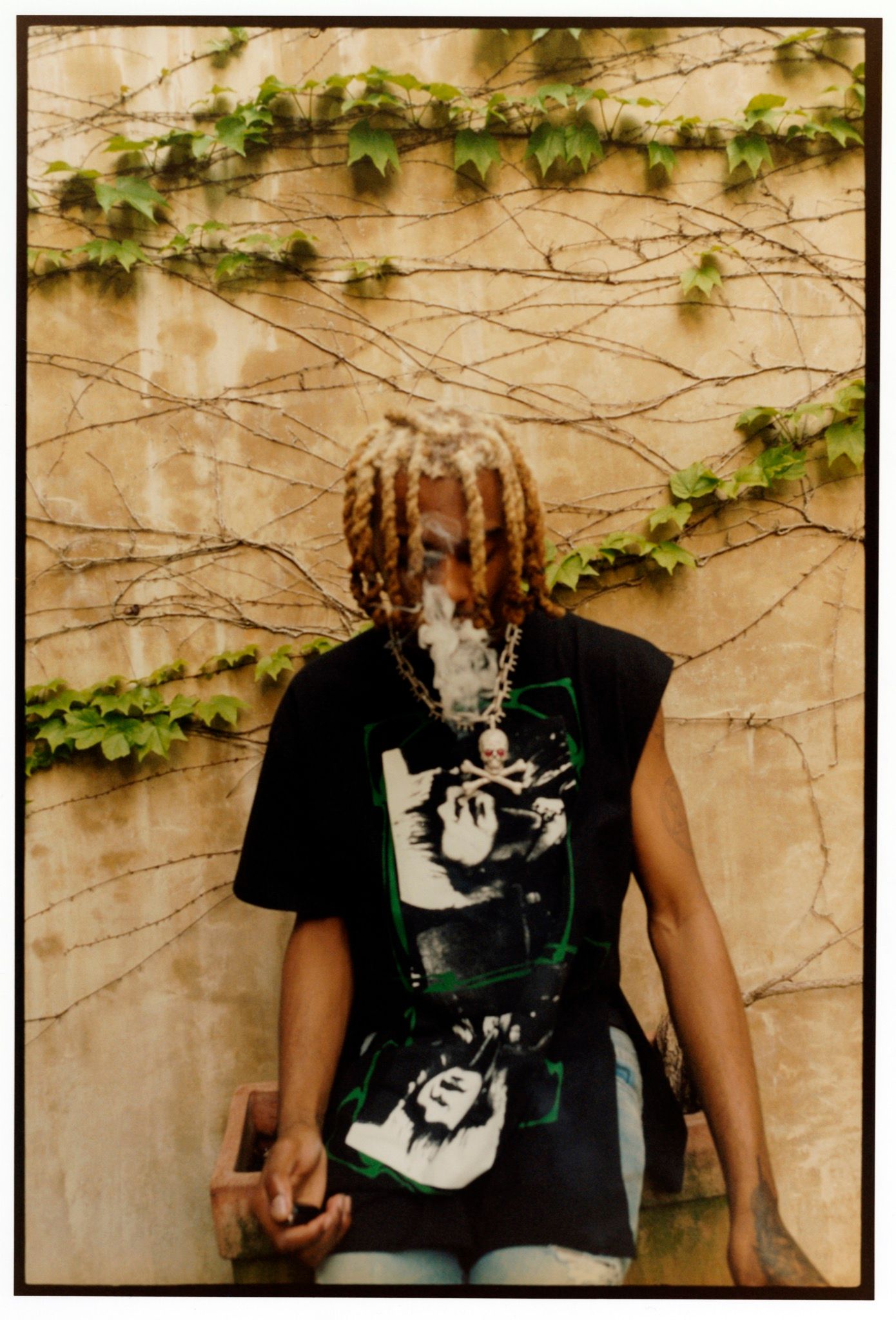

It’s sometime after midnight, and Playboi Carti is showing me a 1995 episode of The Phil Donahue Show. A row of punks of all shapes and sizes, two parents whose son died in a stage-diving accident, and a fresh-faced Marilyn Manson are lined up on the stage of the talk show, answering questions about the new satanic trend that is decaying America: moshing. “And then it’s going to be me,” Carti tells me, describing his concept for a music video based on the clip. The 22-year-old rapper and I sit in the basement of his compound, somewhere outside his hometown of Atlanta, in a lounge area that looks like the platonic ideal of an affluent suburban home: sectional sofa, carpeting, pull-down projection screen, a Restoration Hardware mirror. The only difference is that there’s a Chucky doll in one corner and an assistant quietly rolling blunts in another.

The screen in the center of the room and the home’s sound system are connected wirelessly to the rapper’s phone, which he flips through sporadically as he ambles around. It makes the house feel like the inside of his mind. When I arrived an hour earlier, he was playing Frank Ocean (Issue 33). Then, a pause. Then, the clickety boop of text messages. Later on, Carti queues a series of anonymous-looking files: drafts of songs from his highly anticipated sophomore album, currently titled Whole Lotta Red. The words “highly anticipated” have become a journalistic cliché for describing upcoming albums, but in the case of Whole Lotta Red, the term is justified. Ever since Carti played parts of the album onstage in Seattle late last year, an entire cottage industry has cropped up around its release, with practitioners devoted to reconstructing and looping together low-quality audio from concert footage or Instagram stories. Reddit threads have unraveled with Da Vinci Code-like speculations about the album’s release. In mid-February, the entire record was “leaked” on YouTube and other platforms.

Thom Bettridge: How do you feel about the snippets and leaks coming out around your album? Does it feel good to know that millions of people are waiting to hear what you’re doing?

Playboi Carti: A lot of it comes from me. I’ll perform snippets on my tour, because I know they’re going to play that motherfucker until it come out. Have you ever seen that movie Hackers [1995]? With Angelina Jolie? I just finished watching that shit. And there are people in real life who do that shit, leaking Carti’s music like it’s a fucking trend. For me, it’s a gift and a curse because I know they want it, but they don’t recognize that I’m trying to give it to them in a different way. The music I want to drop now, I want it to be appreciated for a long time. I put my all into this shit, and I want it to be a timeless piece. If I could, I would drop music all day, but I can’t. And if you’re a real Carti fan, you know that.

Many fans have questioned the veracity of the leaked versions of Whole Lotta Red, not because the songs aren’t Carti’s – they clearly are – but because he’s so prolific that an entire album’s worth of songs could be little more than scraps from his cutting-room floor. The rapper claims to have recorded thousands of songs, including a mass of unreleased music recorded with fellow stars Young Thug, Frank Ocean, and Lil Uzi Vert. The Playboi Carti phenomenon reflects a new order in the world’s most-streamed genre. Rap today is defined by its power as a democratic means of production. It sources new talent from bedroom producers and recording artists who self-publish on SoundCloud, bucks corporate power, and creates autonomy through an artist’s ability to speak to millions directly on social media, or to drop – or leak – a mixtape at any given time. Most importantly, this content is created in the intimate but social space of studio recording sessions, which bring together established artists – with their high follower counts – and knight new talent.

As hip hop has exploded, the Atlanta area has established itself as the heartland of America’s number one musical export. With influxes of talent disrupting the industry, an inherently collaborative work ethos, and an ever-rotating guard of visionary young people – and young money – the Southern city has come to resemble a Silicon Valley for rap music. Carti is a product of this system. Growing up in Atlanta, he spent his teen years skipping school to work at H&M and record music. He looked up to trap mentor Gucci Mane (Issue 35) and made his way under the wing of underground collective Awful Records, who released his viral self-titled mixtape and introduced him to collaborators such as producer Ethereal.

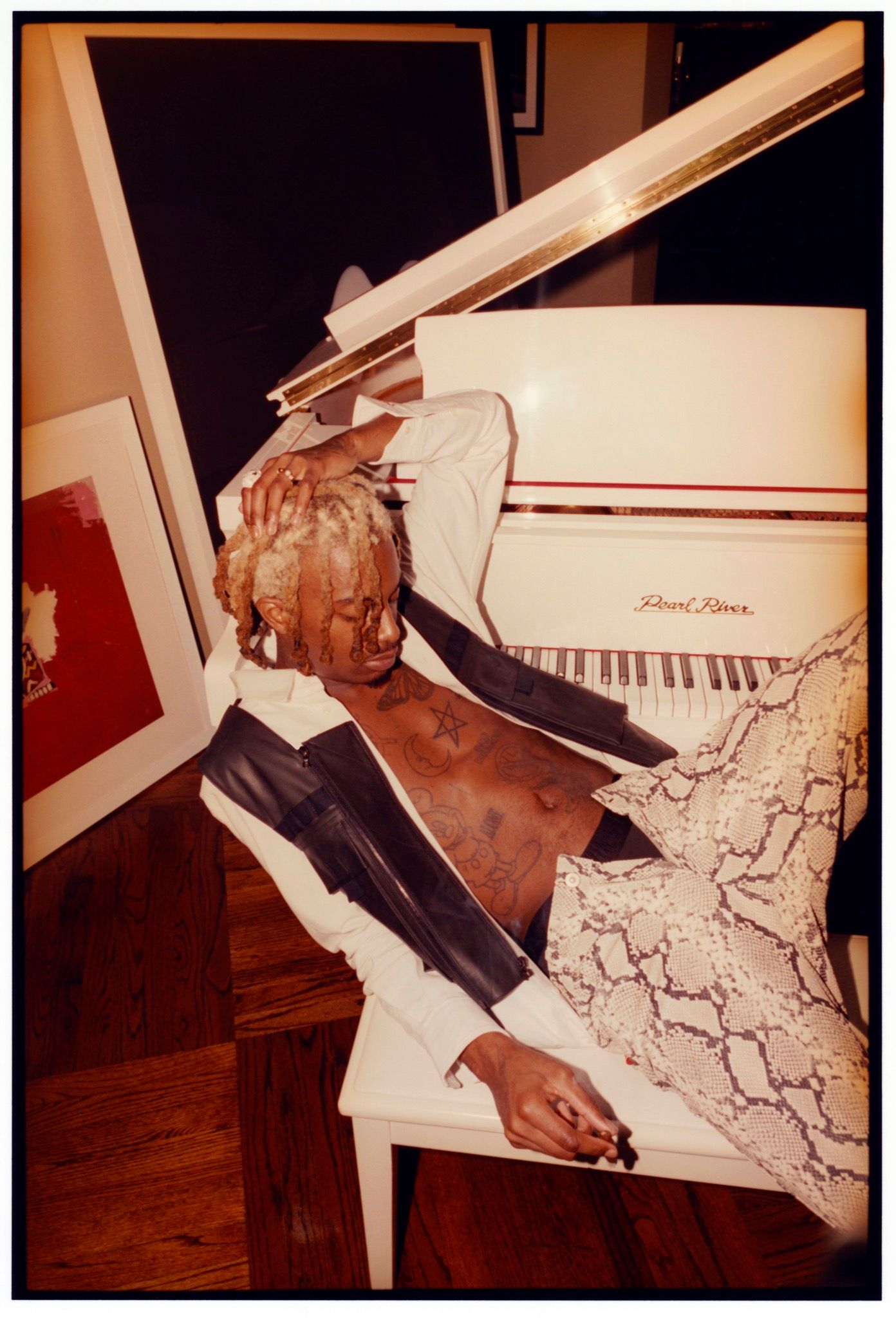

The liner notes of his debut album Die Lit (2018) boast a curated pick of rap’s biggest talents, including Travis Scott (Issue 34), Young Thug, Bryson Tiller, Lil Uzi Vert, and of course producer Pi’erre Bourne, who is almost the record’s musical coauthor. Many of these artists, not to mention hundreds more producers and vocalists both notorious and undiscovered, reside within a five-mile radius of the Atlanta TV room we’re sitting in. “Uzi’s got them,” Carti replies, almost dismissively, when asked about the entire album of songs he is rumored to have recorded with the fellow rap darling. “And I don’t need ‘em.” This statement is not bravado: songs are plentiful here, because this house is not merely a celebrity mansion. It is a machine for making music. Carti is largely nocturnal and records almost exclusively in the early hours of the morning. Of late, he has decided to skip the time it takes to drive to the studio, instead recording all night on a spartan vocal-recording setup mounted on his dining-room table. When I arrive to the compound at 11pm, Carti is just getting his day started, lounging in front of a large spherical microphone in designer flip-flops and a Vetements t-shirt covered in handwriting. Across from him, positioned like an imaginary dinner guest, sits a mannequin head with the letters “IGGY” written across the neck in Sharpie – presumably in reference to his Australian pop star girlfriend, Iggy Azalea.

Unlike many of his comrades, Carti is fiercely private and almost totally averse to social media. His Instagram posts this year can be counted on one hand. When not on tour, he prefers to stay at home or in the studio as much as possible. After greeting me, Carti gets up and dutifully walks to the kitchen to hand me a bottle of Voss water. Aside from the massive jars filled with neatly stacked Oreos and packs of Gushers, the most prominent feature of the kitchen is a framed “WANTED” poster offering a reward for clues leading to an arrest in the shooting of Tupac Shakur, who was murdered on the exact day of Carti’s birth. When asked about the significance of this uncanny shared date in an interview for SSENSE, the rapper was uncharacteristically sentimental: “I wonder if Tupac would have improved my music,” he said. “I want to know how [he] would react – not just [to] me, but to everything that’s going on in the world at the moment.” On this particular evening, Carti is braced by the jittery focus of being in-process. Every polished wood surface in the mansion echoes this feeling – like a processor humming at full capacity. Even the compact entourage on the premises is solemn, as though cautious not to slice through the ambiance too loudly or quickly. In the basement, watching Carti pace around and play track after unmarked track off of Whole Lotta Red, it becomes clear that in this place, what looks like hanging out is part of a much larger ecosystem.

You record a lot of songs that you don’t release. So how do you decide what makes it out there and what doesn’t?

I just listen to shit until I burn out on it.

That song you just played was really good. Who produced it?

Richie Souf. I’m on my Atlanta shit, bro. I made that upstairs, in that room. I’ll just listen to the beat and play it about ten times before I go in. I might say one thing, and then once I say it, I go into the booth. It’s real fast.

Something that stood out for me about Die Lit is the extent to which the vocals are layered …

You’re going to love my shit, bro. You’re saying some real shit, and I’m getting better with the flows than what I was fucking with on Die Lit. I want this shit to be appreciated for a long ass time. I want this to be a timeless piece, and I want to give the people the best of both worlds: because I’m an alien, and I got my own little worlds.

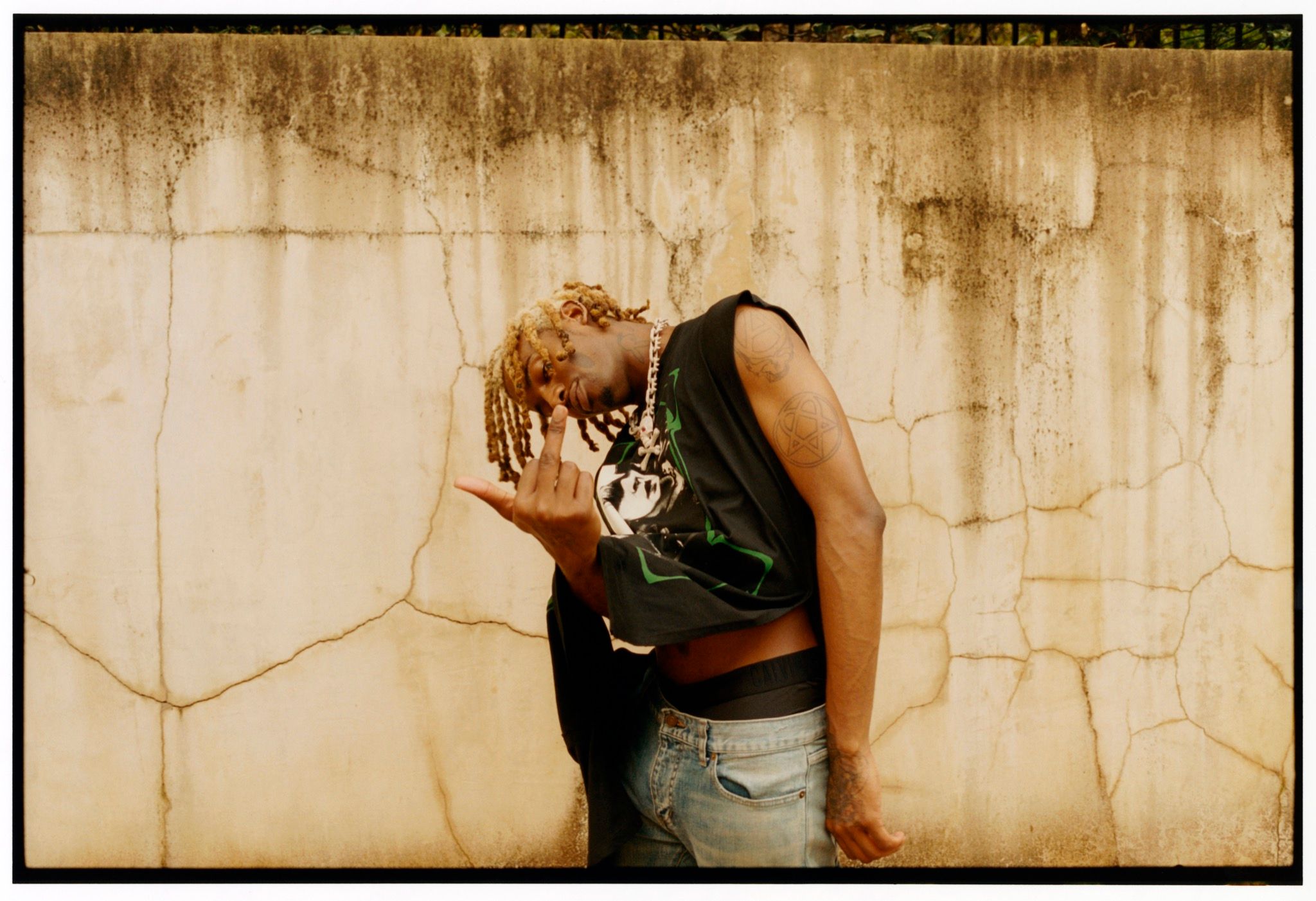

I thought it was really fitting that you played me this mosh pit video because I feel like the big innovation with Die Lit was about bringing punk into your music. How did you get into moshing?

By the end of my first album [Carti’s debut mixtape], I felt like I was almost there. I was just missing something, and we were in Miami going crazy. It was psyched out, and we would just go crazy at the shows. So those real life situations turned into music and that was just the energy.

On the cover of Die Lit is a picture of the rapper captured mid-front flip above a pulsing crowd, both of his middle fingers extended. (“I’m really into Bam Margera,” the rapper told Dazed & Confused around its release. “He’s like, crazy. Psyched out.”) The image is reminiscent of Yves Klein’s famous Leap into the Void (1960), which shows the artist seemingly throwing himself out of a Paris window. Not documented in the photo were the friends he recruited to catch him below, stage-dive style. Klein’s thesis was about illusion, but Carti’s is straightforward: this is rap music you can mosh to. The use of vocals as a blunt musical instrument is central to the trap music that made Atlanta the creative core of the American music industry, but with Die Lit, the young rapper took the idea into uncharted territory. Carti’s most recognizable vocal tools are his ad-libs: the screeches, whines, exhales, and pops that punctuate his songs, which carve offbeats into the rhythm and layer psychological and sexual tension onto the music. Die Lit’s most successful moments are when these guttural noises in the background become the main vocals themselves. This is what fans describe as “Baby Voice Carti” – the rapper at his most alien. Take “RIP Fredo,” a 2-minute-and-40-second song in which Carti says the words “notice me” 32 times. Each iteration of the phrase stretches its meaning across wider psychological terrain, ebbing and flowing between “didn’t notice me!” (excited about getting away with something), “notice me!” (a desperate plea for attention), and “didn’t notice me?” (words laced with disappointment). As the words disintegrate throughout the chant, “notice me!” slowly begins to sound like “know it’s me!” – an anxious command for recognition. Elsewhere, the slippery quality of words is used to more poignant effect:

N***a be dead to me

N***a be dead meat

Using repetition to emotionally unravel simple phrases is something Carti did in his first SoundCloud hit, “Broke Boi,” which climaxes with the rapper saying the song title ten times in rhythmic succession, each time taking on a different possible feeling: “the broke boi everyone looks down on,” “the broke boi everyone used to be,” “the broke boi I used to be,” “the broke boi that I hated being,” “the broke boi I might still be now.”

When do you feel that things really changed for you? In terms of success?

When I started being able to buy my mom shit. When I could take care of somebody else and still be straight, that’s when I knew I was in a different place.

That’s a good feeling.

Because I was dropping songs on SoundCloud, I thought I was doing something, but I wasn’t doing nothing. That was my social media, you feel me? When I was on that, it was like, “Yo, I’m really not trying to be where I’m at. I’m trying to get up out of here.” When I was dropping that music, I was skipping school to go to the studio sessions, because I knew I had to get out of there. The moment somebody told me they like my music – it could’ve been one person – that’s when I knew that shit was going to change for me. Just, “Yo, I like your music.” That gave me the push.

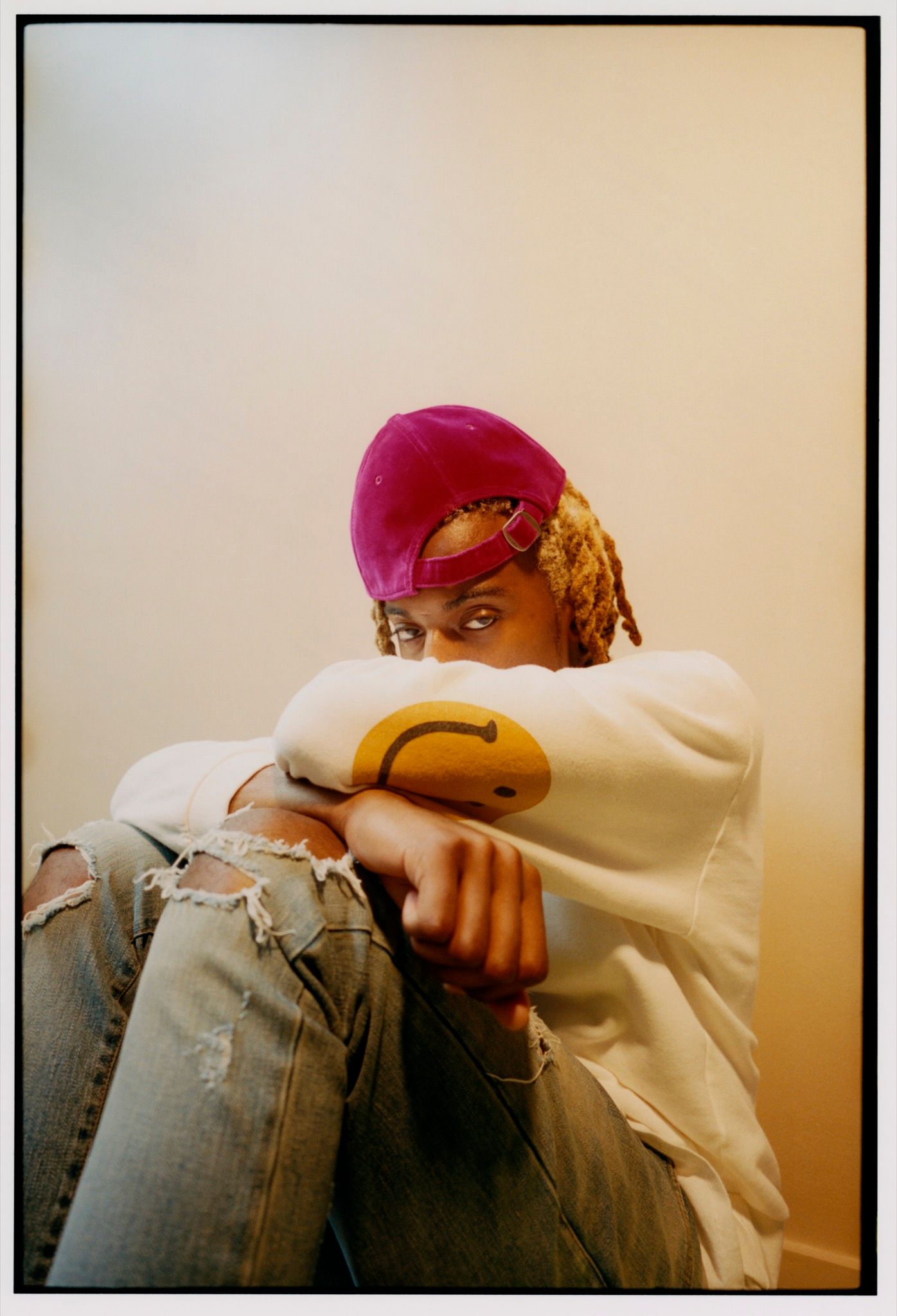

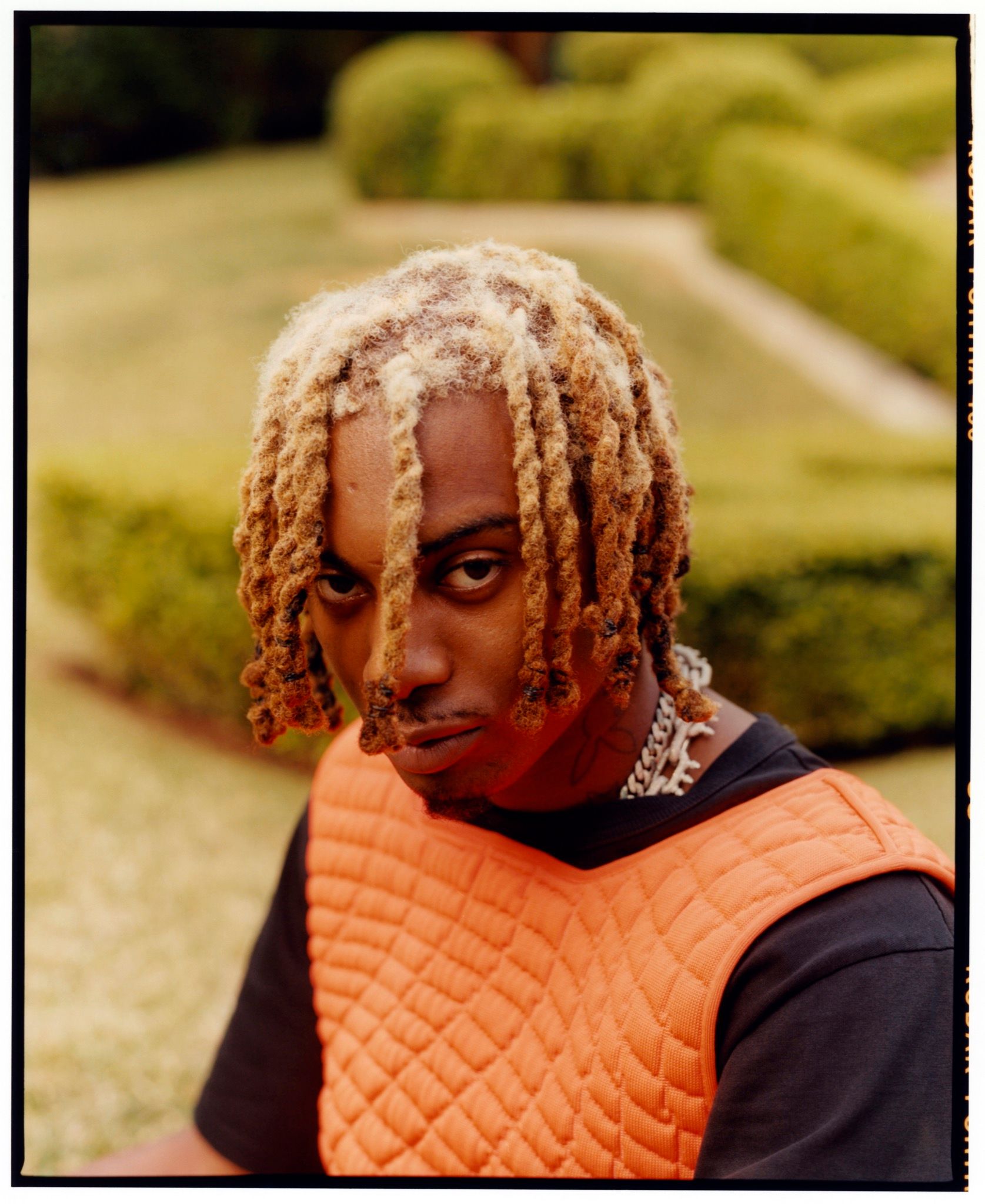

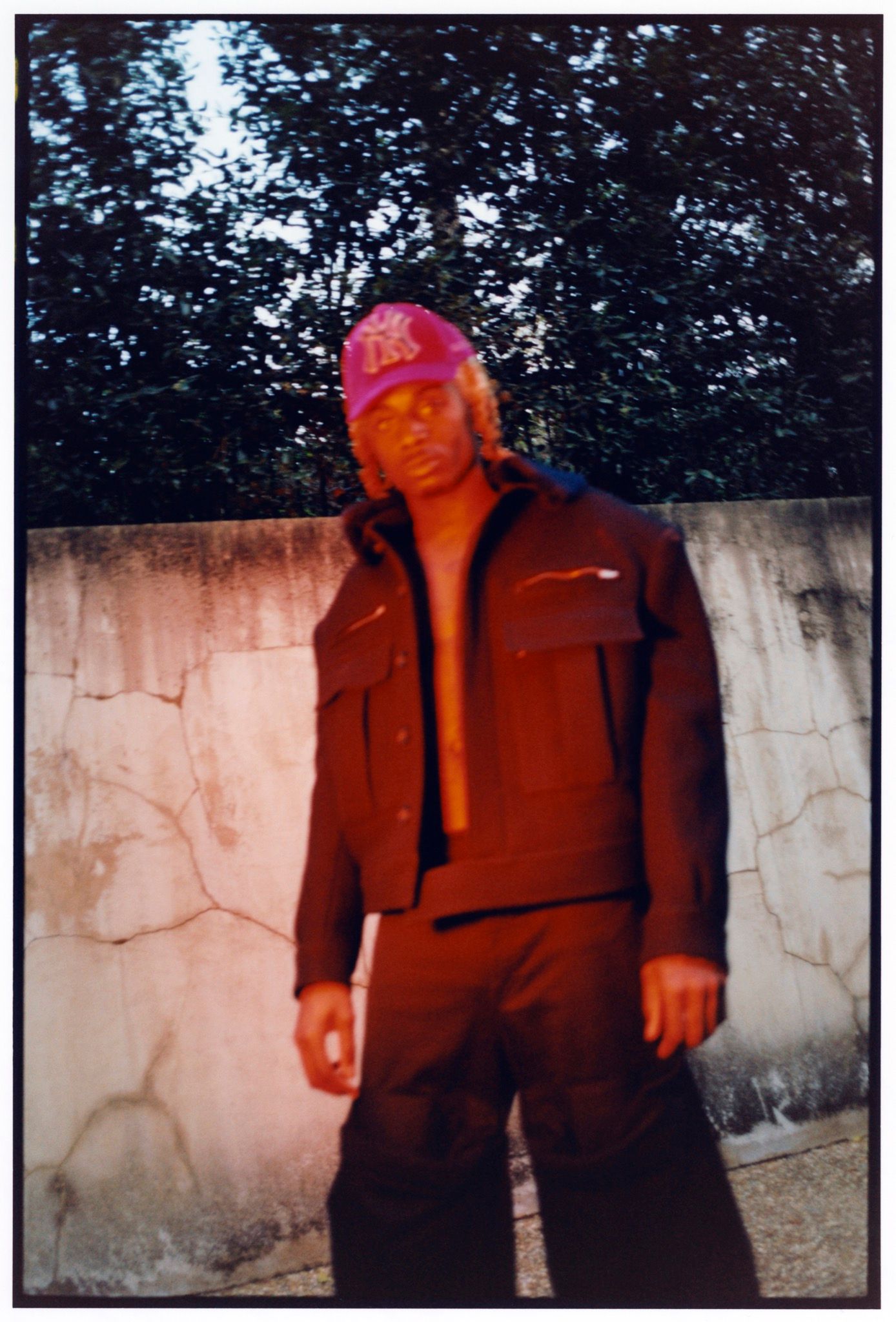

Despite getting his start in the Southern rap scene, Carti shot into the mainstream most visibly through his relationship with the New Yorker A$AP Rocky, a rapper who, like Carti, is known for his open fascination with high fashion. Yet unlike Rocky, who arrived at a time when shouting out Raf Simons in a rap song felt like a novelty, Carti represents a zeitgeist in which fashion and rap are intrinsic to one another. With the stature of a runway model and a striking face marked by a large birthmark on his left cheek, the rapper made his first fashion week appearance walking in Virgil Abloh’s Louis Vuitton debut. The following season, Carti opened Abloh’s AW-19 Off-White presentation, which also starred fellow Atlanta rapper Offset. In a video shot backstage, Abloh goes to meet the two musicians in their green room to thank them for walking. Before leaving, the designer takes a moment to check Offset’s styling, then pulls a fat handful of diamond chains out from under the purple Off-White puffer he’s wearing, as though to say, “Let’s not hide that you arrived here wearing these.” In runway photos of the show, Carti’s own spikey diamond chain is also on view, resting neatly on top of his sweater.

When you sit down to make music, what do you do first?

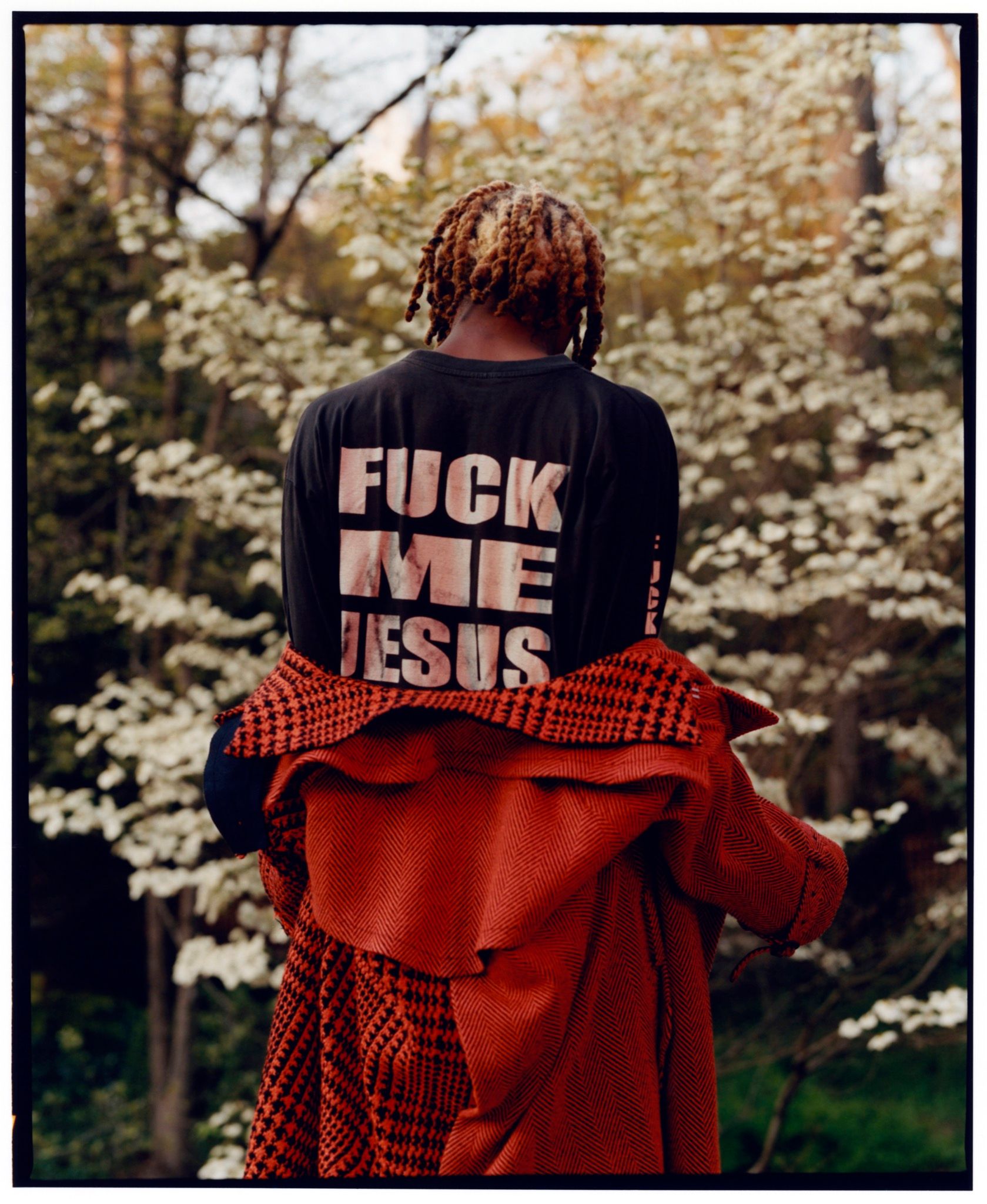

I put on clothes. I wear my best outfits to the studio. I like expressing myself with everything I put on. It’s a challenge, and not everybody can do it. Just like music: timeless pieces, timeless clothes. I got certain shirts I can’t wear because I remember when I did a show in it, and everybody else does. So I can’t wear it anymore because there’s a picture of me in it.

So what do you do? Sell them?

No, I keep them at home.

Do you like shopping yourself?

I go on shopping sprees because I’m a shopaholic. I’ll go buy clothes and antique pieces, or go buy my girl shit. Selfridges really fucked with us. We’d go in there and spend like 50 thou, but I won’t do that anymore.

When the stylist for the next day’s photo shoot arrives, Carti’s focus shifts in a way that seems to flip the energy of the entire compound. He’s eager to pair whatever she brought with pieces from his own wardrobe. Next to his basement den, Carti has a room the size of a studio apartment filled with racks of designer clothing. And there is another one upstairs, near his bedroom. As the stylist’s assistant unpacks, Carti fingers through the garments carefully. “Is this a runway piece, or are they selling this in stores?” he asks about a Craig Green coat. No one knows the answer. He stops again at a selection of Vivienne Westwood, which reminds him of an idea he once had for tour merch: a remake of a famous shirt worn by Sid Vicious, featuring two burly cowboys standing face to face with their dicks touching. The next thing to stop him in his tracks is ALYX. “That nigga Matthew gave me all of this already,” Carti says, referring to the brand’s creative director, Matthew Williams. Within minutes, half a season’s worth of ALYX menswear is brought down from upstairs.

Half an hour perusing his collection and two racks of additional clothing later, Carti overhears me asking his assistant what’s in the garage. He decides to take me himself. Past a professional motocross bike and shelves overflowing with collectible sneakers, we come to three cars: a Range Rover, a Rolls Royce, and a Lamborghini. The way he presents them feels matter-of-fact, as though he’s showing me his ID. It’s all a networked organism – the clothes, the Chucky doll, the iPhone, the Oreos, the house stereo system – each item a part of one total artwork. “The ultimate, orgasmic expression of everything that ails us in this culture.” Donahue’s words perfectly describe the mosh pit that teems within Carti’s work: the desire for fashion, sex, and recognition that passes through this house and into a microphone on its dining-room table. As we leave the garage, I hum the opening chorus of Die Lit under my breath:

“Just to feel like this it took a long time.”

Credits

- Text: Thom Bettridge

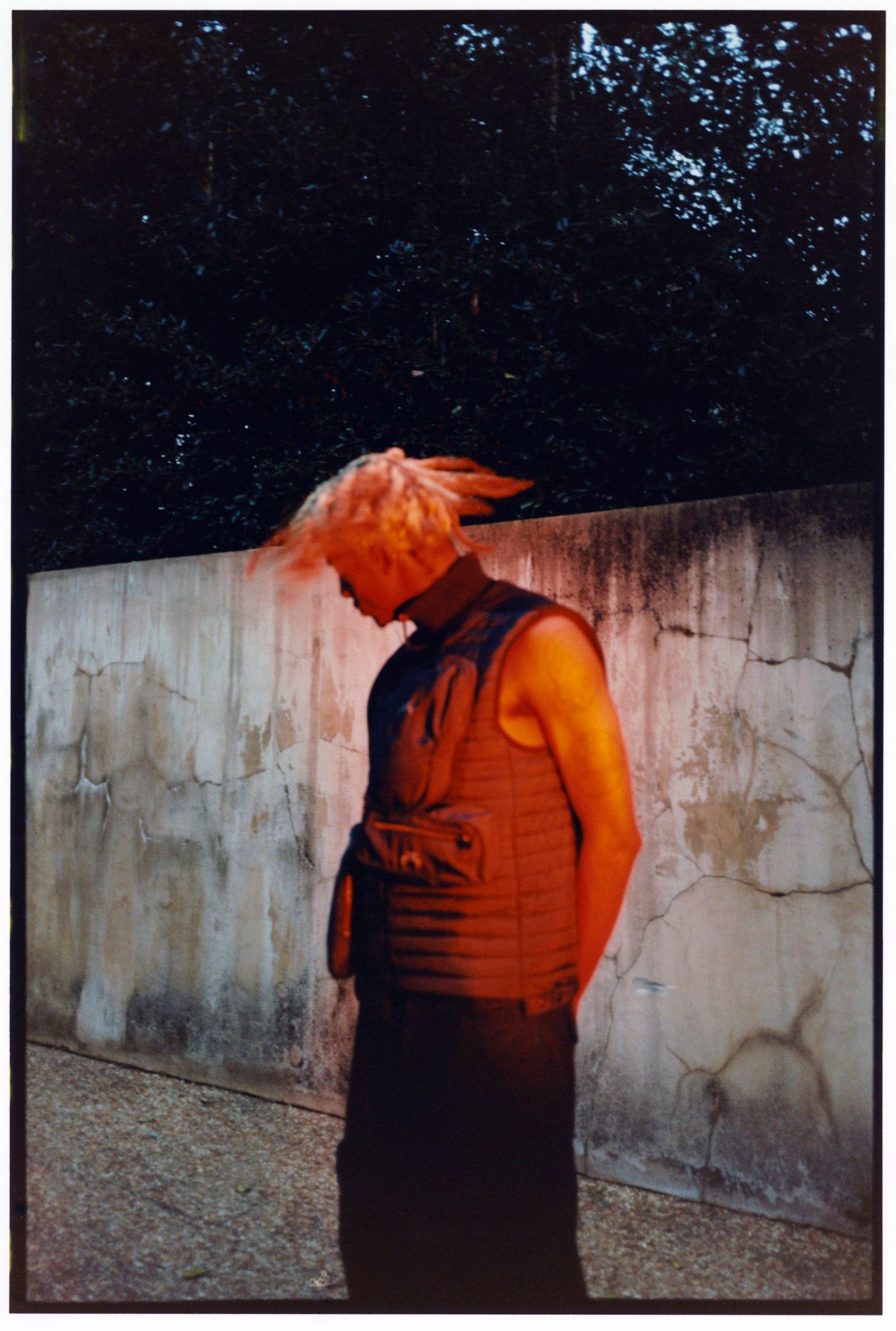

- Photography: Renell Medrano