Indefinite Optimism: A-COLD-WALL*’s SAMUEL ROSS

|Jack Self

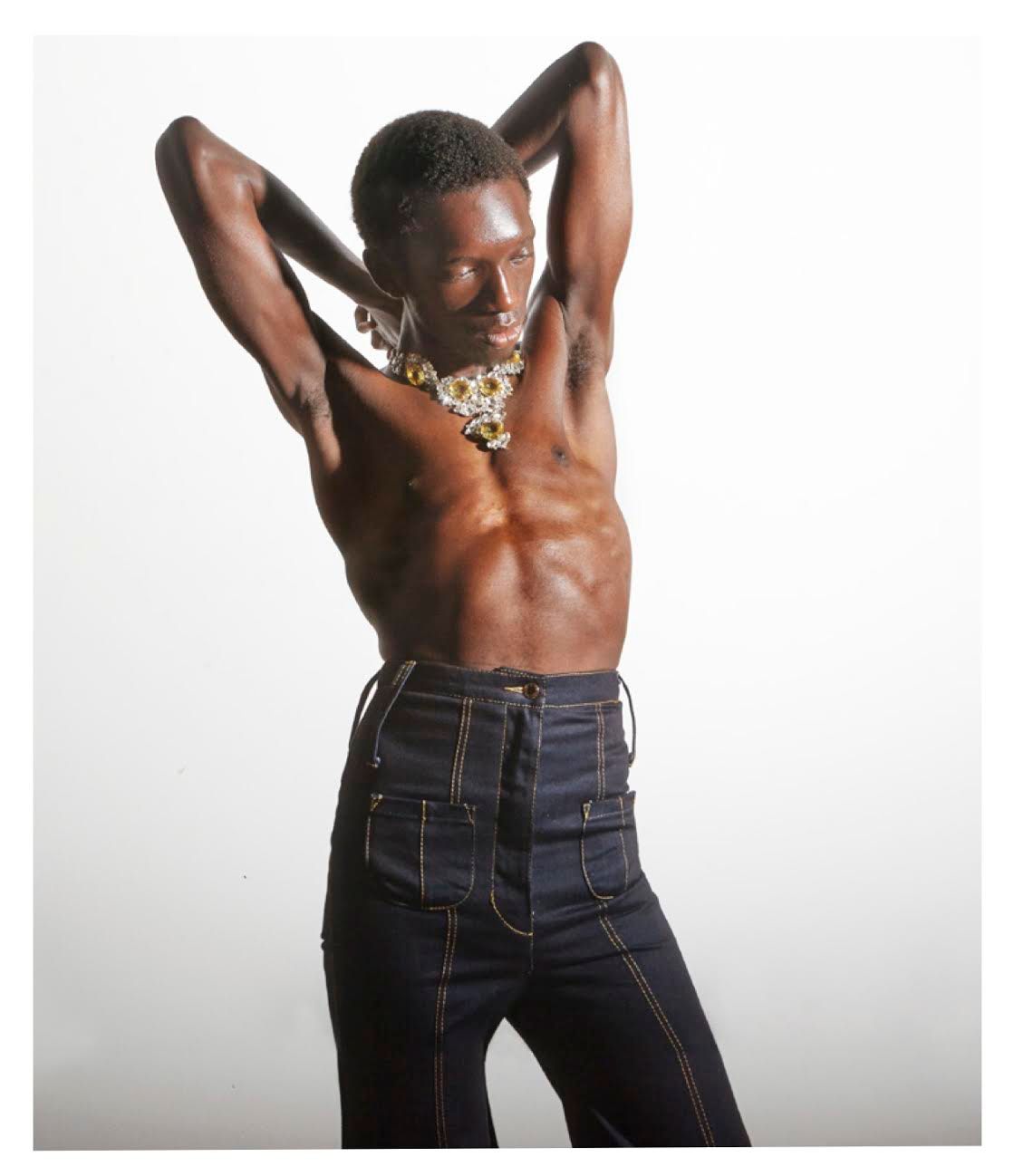

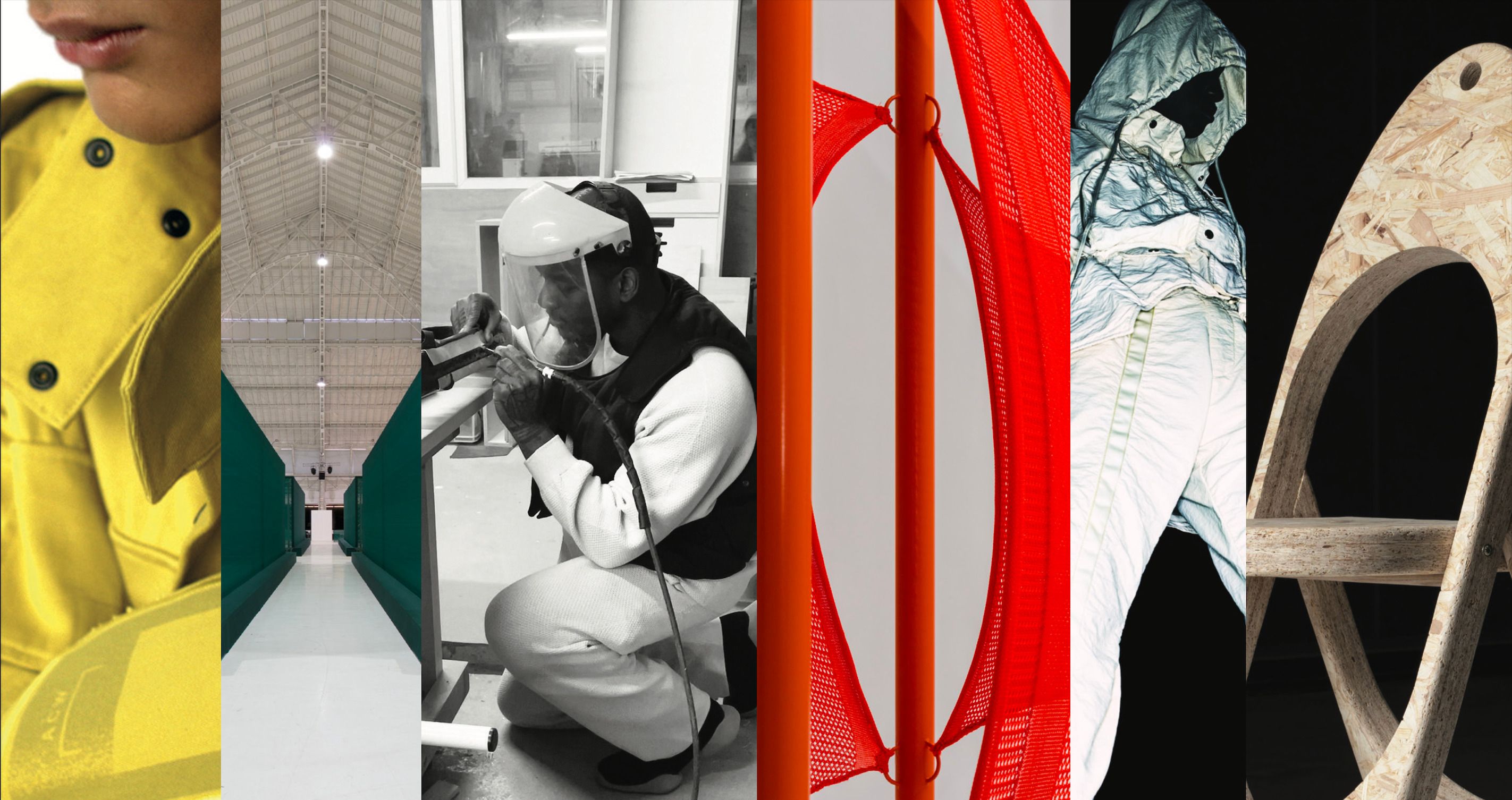

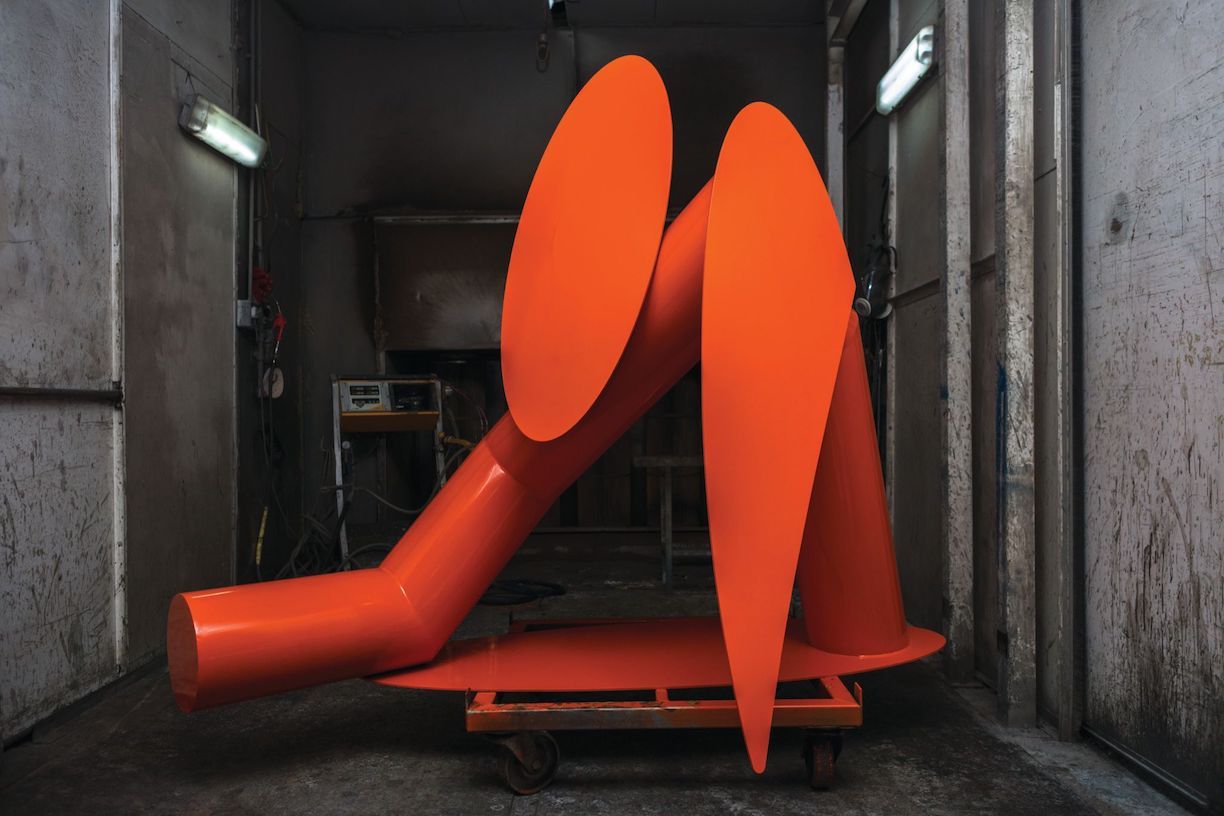

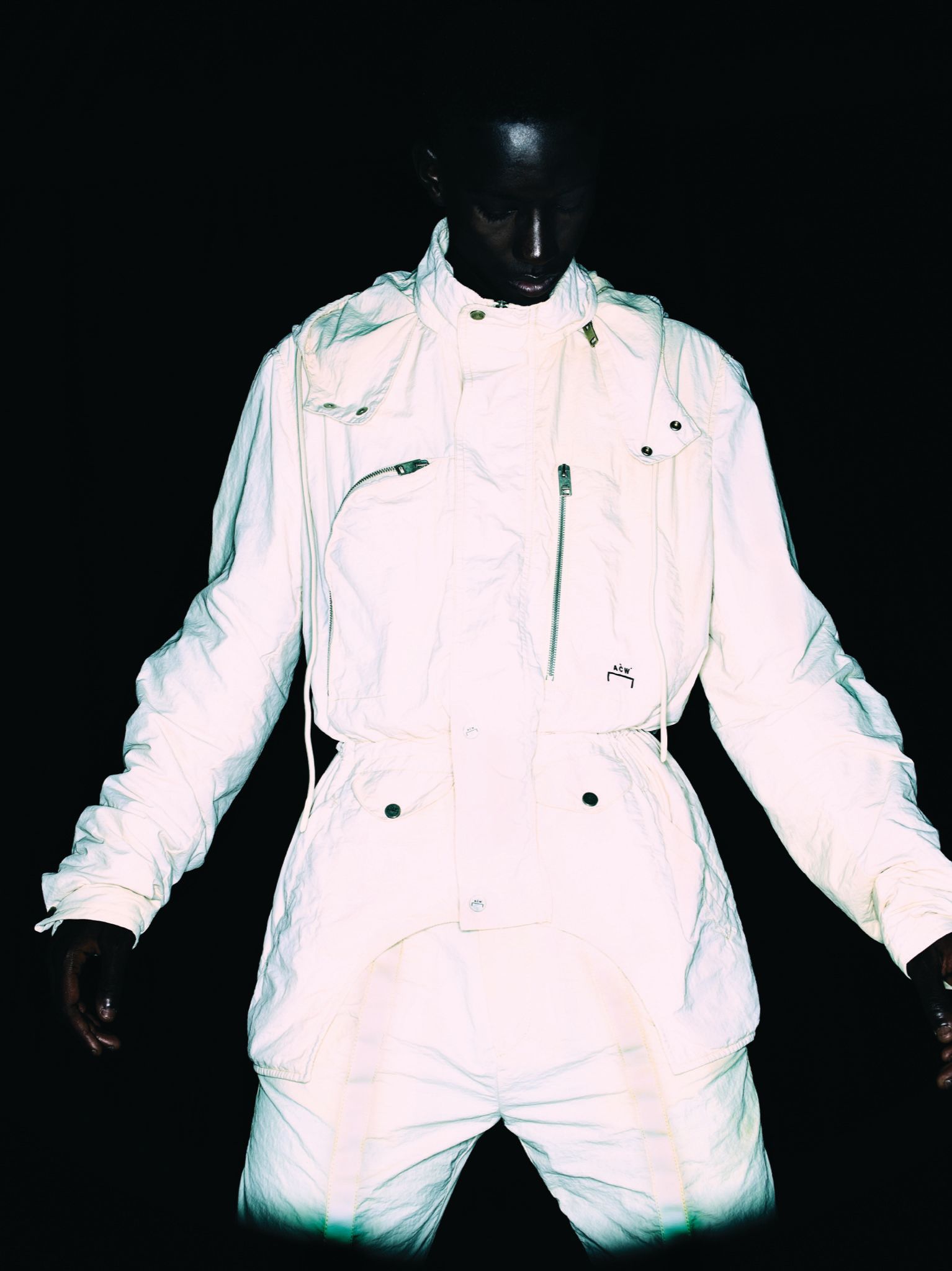

SAMUEL ROSS, who was born in Brixton to second-generation Windrush parents of Caribbean descent, is best known for his fashion brand A-COLD-WALL* and his design and artistic production under SR_A. He explores the social issues, disparities, and realities of both British and global cities through design, calling his approach a “material study for social architecture,” aesthetically informed by “graphic design, British class systems, and brutalism.” Last month, Ross released his first book, Object – Form. Form!, a 457 page celebration of his work thus far, which includes texts written by Virgil Abloh, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Grace Wales Bonner, and more. For Issue #39, we sent the London based architect Jack Self to speak to Ross to about the political disposition that has shaped his dynamic career.

Samuel Ross is a designer whose medium is the field of design itself, in all its forms – interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, but never undisciplined. However, his philosophy of design extends far beyond its classical conception to encompass a holistic vision for contemporary life – implicating our environmental responsibility and the pursuit of social justice, and promoting class mobility. I began by asking Ross to summarize his attitude towards fashion.

SAMUEL ROSS: My attitude towards fashion is a purist’s. I came to fashion quite late, around 19 or 20. Up until that point, what I now understand as fashion was just this organic cross-pollination of ideas and semantics. I could read the codes of a garment: how it reflected your environment, your self-image, your demographic. For myself, that meant the semantics of working-class England.

I haven’t necessarily added color or race to that list above, because at the time, when I was going through school, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a lot more integration than before. This was largely down to the efforts of the British New Labour government. There were numerous shortfalls, of course, but there were also massive leaps and bounds made toward greater social mobility and multiculturalism. I benefited from free school travel and the Emergency Maintenance Allowance, a weekly payment to full-time students, and that support made it possible to get into free enterprise in fashion, to get out of the council estates and actually travel to my college. A lot of what I do today is politicized because of the leftist politics of that era – which were way more experimental at that point in England. They played a huge role in my being able to have a career versus just a job.

My first real engagement with streetwear fashion came from meeting a gent on my graphic design course in Northampton College. He would give me counterfeit and stolen Adidas and Nike on consignment; I would sell the goods and pass him back his share of the profits. This is how I became really well versed in training garments. But I wouldn’t say I had any real understanding of streetwear, because growing up outside of the main metropolitan cities, you’re outside of that zeitgeist. Streetwear wasn’t a look, it wasn’t affected, it was just a part of everyday life. I was always attracted to these types of garments, but I didn’t know there was a whole subculture behind them. Of course, when I look back, I see that we were literally living the subculture that is being so fetishized now, even if we weren’t aware of that at the time.

“I’d rather be with hypocrites than cynics.”

Jack Self: How did you begin A-Cold-Wall*?

I started working in fashion and streetwear after starting my first label at 19. Then I went to study graphic design and contemporary illustration; I graduated and became a product designer. I crossed paths with Virgil Abloh and became his first assistant. After traveling around Europe and North America for a while, I began to understand there was a kind of international cultural conversation that was exclusive to the world of fashion. This expression of the zeitgeist wasn’t happening in any other industries, which is why I moved from product design, graphic design, and advertising into fashion. After three and a half years working solely for Virgil Abloh and Donda – helping and assisting on all types of brands, from Hood By Air to Been Trill to A.P.C. Kanye to Yeezy to stage design to, of course, Off-White and Pyrex Vision – I decided to start my own endeavor. I knew this had to be an anthropological reflection on my own context: on working-class British society, on the social dissonance, and on the architecture that I had lived in and around.

It was a conscious decision to move into fashion – not necessarily because of clothing itself? I’ve seen this a couple of times among successful designers of your age, which I guess is now becoming a generation. It is a move in which fashion becomes a platform for a multidisciplinary approach. It also brings with it other types of benefits – social mobility, being able to enter a space which is nonjudgmental about background. Is that a fair categorization of how you experienced fashion at the time?

Yes. Fashion could be summarized as a kind of indefinite optimism. For some reason, I found product design to be pessimistic – a discipline with low expectation and a resistance to moving forward. I felt increasingly dissatisfied. I graduated with a first-class degree; I’d done everything right, everything expected of me; I got job interviews at traditional agencies. And yet, I didn’t feel any excitement, I didn’t see any desire to enable young creative minds. So, I opted out and moved to fashion, which is full of hypocrites, even if it is far less cynical. I’d rather be with hypocrites than cynics.

I think what you’re describing is typical of a certain millennial disillusionment with the pathways being offered by society. By the late 90s, it was clear the social contract of free education, rising wages, affordable cost of life was breaking down. The trend became irreversible after 2011, which in my eyes was the most insane year of this century so far – 2020 included. It was the year of the Arab Spring, the Occupy movement, and the UK’s August riots, when cities across Britain burned for days on end – a response to racist police violence, in a way that prefigured the Black Lives Matter protests. The Americans also killed Osama bin Laden, and there was a Royal wedding. It was an incredible turning point in the current era. The spirit of that period – between the global financial crash and the Brexit and Trump victories – seemed to be one of profound disillusionment, especially for working-class people. Did that turn influence your creativity, or how you advanced yourself and your ideas?

Completely. There was still this idea that you were obliged to physically commute from the suburbs to your job, and be housed in these fixed places, with stable communities, and aspire to own some nice Victorian prospect. But a decade into this century, that was quite clearly a fantasy. This description overlaps heavily with Mark Fisher’s thesis on “hauntology” and the death of the future. The future has become an inaccessible, static place, and is no longer an action we perform as a society. All of this was starting to become quite visible, and I felt there was a dissociation, a societal cognitive dissonance between what I was taught my future should be and what the immediate future could offer. That’s really why I decided to move out of the traditional system and pursue a much more adventurous and untrodden path. As a 21-year-old graduate, I was reading about the great artists and designers of the 20th century – and the options society was offering me did not look capable of leading me to any of those artists’ situations. I quickly figured out that staying complicit and submissive in this system of mediocrity was not going to take me anywhere I wanted to go. The only choice seemed to be to implode that whole process and take more risks.

“There is an extreme tension today: on one hand, a desire to replace old hierarchies – to send clear signals to other people of color that they belong, and they can exist in such spaces of privilege; and on the other hand, a need to completely dismantle and challenge the entire social system.”

The dimension of risk is a whole conversation in itself. But I want to come back to this description of fashion as “indefinite optimism.” In our description of the years around 2011, we are pointing to the moment that grand social narratives were completely dissolving. These types of big stories we tell ourselves are essential to confronting why society operates in the way it does – to answering the question, “What is it all for?” The old narratives about pacts between various structures of power are no longer functional – but they have not been replaced by any other clear sense of why our civilization exists. That leads to a lot of existential anxiety, at the individual and collective level. Against this, one of the things I admire most about fashion is the way in which it constantly generates new narratives and new meanings. Fashion is a vehicle for storytelling – whether literally, through the aesthetic references, or through art direction or branding. Was that part of your attraction to it as well?

To speak really simply on this, I came from an area where a lot of people in my immediate circle did not go into higher education. I was fortunate, I went to uni – not a great one, but it brought me to a new city, to a nucleus of education and ideas that were being thrown at me through how people dressed, how people spoke, the music genres I’d never heard before in my life. I’d come from a place where fashion did not exist. We only had uniform. People wore uniforms to work, and you wore uniforms to signal what tribe you were a part of – mine being nylon or Nike grey jersey. We didn’t have fashion. That wasn’t allowed in our space or scope or projection of our identity. Those ideas don’t exist in middle England for the working class at all. Unless I was to head back into central London, I would not see a Gucci or Louis Vuitton or Dior bag or Burberry overcoat. When I arrived at university, and I saw this incredible optimism about identity being expressed through objects and garments, it reaffirmed what I believed might be the importance of fashion.

Fashion is the ability to paint and transform and reinvent oneself. It is also the opportunity to almost encrypt a communication between different groups. It’s about how you reshape material around a moving form to then convey a spiritual, cultural, or societal virtue. That’s what I’d say fashion is. On the other side, garment design – and I’m just as passionate about garments and apparel, actually, as I am about fashion – is about innovative fabrication, sustainability, function, material and textile properties and capabilities. I sit right on this line between fashion and garment design.

You recently worked on a collection for which garments were sold separately from their hardware. For many brands, it is the hardware – zippers, buckles, clips, and so on – that fundamentally defines them. So to sell the hardware separately is to strip out branding from product, or mood and spirit from object. The gesture opposes the logic of maximizing profit and inserts an element of random, bespoke creativity that comes from the owner, who is now also a co-creator, an active agent in the fashion process. As a strategy, it seems to fit within a legacy of unpredictable, anti-establishment, and DIY British movements such as 1990s sound system and rave culture, and of course punk. Your mix of commercial logic with a certain memory of punk is resonant to me, and perhaps to others working at the intersection of more than one industry – which involves learning to speak the specific languages of different marketplaces and different contexts, in order to make oneself better understood and one’s ideas realized.

It’s a weird one, because my personal beliefs are socialist and anarchist and anti-capitalist, but I’m really good at communicating through the capitalist lens. In the last decade, we’ve seen the political pendulum swing back toward a social-minded perspective, one that is far more left-leaning and decentralized in terms of power distribution. On the other hand, there’s also an understanding that this is late capitalism, that it probably won’t last very long, so it is getting really extreme and wild – almost as though we need to ride the wheels off it prior to this impending macro-change.

The macro-change is already underway. The last year has had the feeling of an imminent new renaissance. I don’t mean that we’re already within an incredible moment of rebirth and creative explosion – the Renaissance was not an endpoint in itself; it was a bridge between the medieval and modernity. But what I feel right now is that we’re at the end of a particular model of capitalism, and although we don’t know what the next great paradigm will be, it’s very clear that the old paradigm has ended. We’re at the end of our own medieval era.

If that is true, then we also have to discuss throwing off the feudal aristocracy. Maybe that’s already beginning to happen – I think of my ancestors, who didn’t have the opportunity to be in any of the spaces I occupy today. There is an extreme tension today: on one hand, a desire to replace old hierarchies – to send clear signals to other people of color that they belong, and they can exist in such spaces of privilege; and on the other hand, a need to completely dismantle and challenge the entire social system.

Becoming fluent in the language of capitalism is not ultimately useful if you end up becoming coerced and incorporated and co-opted. It’s a question of learning the language of your oppressors precisely in order to overturn or diminish their power.

I completely agree.

At least since 2011, when “we are the 99%” was coined, and more clearly in the last five years, we have entered a new civil rights era. Black Lives Matter, Extinction Rebellion, #MeToo, and many other social movements have all arisen from urgent contemporary struggles. However, one of their main effects has been to reframe the past – to change historical narratives to increasingly include the voice of the oppressed and not just the oppressor. I’m reminded of a quote from Nineteen Eighty-Four: “He who controls the past controls the present, and he who controls the present controls the future.” Taking control of the means of production is the 20th-century model of socialism. Today, we must take control of the means of the production of time if we are to be free.

It’s impossible for me to avoid mentioning Sondra Perry’s brilliant piece of literature Typhoon Coming On, which talks about the Black diaspora operating as a decentralized “monolith,” as a sprawling network of communities, fractured and encrypted, which has really flourished during the Internet age. I have some minor issues with the term Black in this context – because it erases a lot of diasporic qualities which are not only Black – but what it does highlight is the fact that the diaspora has been extremely successful as a model of resilient, horizontal, lossless communication: the Black diaspora possesses such dynamism and fluidity. The success of a movement like Black Lives Matter is in part tied to the strength of this sprawling network, which is still essentially invisible to those who are outside it. What fueled BLM was this combination of a network primed for mobilization with the sudden spike of pain linked to Covid and racial injustice. The squeeze of inequality has intensified in the midst of this global pandemic, and of course it’s the bottom layer and the underclass of society that are really inflamed – the majority of which is people of color. If we turn this organic condition into a strategy, it involves cooperating with capitalist systems only in order to rise within them and so propagate disillusion and deconstruct them. I think that’s exciting, where we take capitalism and take the screens associated with it, then reverse or syphon that capital and redistribute it. That is happening now, today, in real time, as we speak.

W.E.B. Du Bois proposed the idea of double consciousness – which is the theory that Black people must first think of how they want to be in the world, and then second think about how white culture will perceive them through the lens of Blackness. A contemporary articulation of this idea, developed by Ekow Eshun, says that the ability to view the world twice – through one’s own eyes and through the eyes of another – is an inherent advantage of the Black diaspora. We are starting to see the emergence of a Black diasporic philosophy that is no longer built upon Western ideals of political economy, Marxism, or feminism, but from and for itself.

The W.E.B. Du Bois point, and the notion of double consciousness, is something that Grace Wales Bonner and I speak on at length fairly regularly. When you asked earlier about how I navigate those two nodes of capitalism and subculture, it’s really a case that mirrors double consciousness. The capitalist side of me is operating within a more or less anglophone space. And the subversion is coming from a moderately radical and reasonably educated upbringing moved by Du Bois’ writings. It’s a reality that most go through, but understanding how to harness this double consciousness and not go to war with it is important but difficult.

Trying to destroy a particular political and economic system without being able to locate one’s ideology outside of it is a paradox. If we take the example of the brilliant Caribbean Black Marxists congregating in Brixton during the 1970s and 80s, the problem that you rightly raise is that that Black Marxism is still Marxism, and that is a system that is not enabled by Black thought or the Black body.

It is too soon to talk about what the consequences of the pandemic might be, but I see the potential for a hard reset for a lot of the social processes that were in play before Covid. It’s been a period in which injustices and inequalities that existed previously have been accelerated and exposed, in extreme ways. Most people, I think, have had some form of transformative experience with their relationships with time, and with the meaning of their own lives. I wonder what your experience of 2020 was, and whether there’s been any impact on your thinking about the present and about the future?

The overlap of the pandemic and the new civil rights movement has probably been the biggest turning point of my life. Although an idea of glossy individualism has been celebrated for the past six or seven years, the pandemic highlighted an idea of shared liberty, and a collective spirit. I think we lost that between 2012 and 2019, when individualism was in vogue. A civil rights movement coming to the forefront has reaffirmed my views of how capitalism should and can be used against itself. I took no pleasure in seeing global society on its knees – although you could argue that now is the moment of the system’s greatest weakness. For me, the pandemic has been more about reflecting on new ways to divert privileges that have been awarded and push them back into just causes. The idea of the “just cause” also returned in 2020. Individualism has been challenged, and we are talking more and more about community. The idea of independent communes is returning, and that feels good. As you know, every 20 years we get this cycle, and with it a small window for society to change. Being conscious of that, on my side, I’ve redoubled my efforts to push for change.

It’s ironic that this has occurred at a moment when the public sphere is suspended. It’s difficult to protest physically, yet we’re seeing higher levels of solidarity, communality, pluralism, and inclusivity – even among people who have been alone for more than a year. To return to the idea of risk, someone who is not afraid of losing everything, or who has nothing left to lose, becomes a threat to authority. We’ve arrived at a position in which many people who are at various types of structural disadvantages are no longer interested in performing the kind of empty rituals they were performing before. And many people who have some privilege appear decreasingly concerned about losing that. The risk of calculation has changed. Many of us are desperate and depressed, but simultaneously hyperactive, with a kind of mania driven by claustrophobia and grief. People who feel this way will be prepared to take greater risks.

It’s funny, it’s taken a physical arrest of free movement for people to actually sit and reflect – on the lost idea of utopias, on the idea of progress – and to really pay attention to injustices, to really understand the illogical decisions made by governments. That’s been the silver lining of all of this: the time to just think.

The final question I want to ask you is really directed at the people who might just be graduating from high school now, or who are in their early 20s. It can be very hard to remain optimistic at the moment. Do you have any advice to those who might be seeing opportunity slip away from them, or feeling the long effects of this suspension of the public sphere?

I’d say this: push forward into those far-flung places of radicalism and experimentation that may be drawing you in. We are all at a crossroads, and we must all pick a path. If age is on your side, then you’ve got nothing to lose. Don’t meander around in an assumed reality that is completely speculative and fictitious – go right down the rabbit hole. Whatever the pull of the zeitgeist might be for you, go there. Explore the unknown territory; don’t go where it’s safe. No, don’t go there. Let the journey be unexpected.

Credits

- Text: Jack Self