SECOND ACID WINTER: The Roots of Fashion’s Rave Revival

|Calum Gordon

Last month in Seven Sisters, London, Sports Banger hosted its first (off-schedule) fashion show. The brainchild of Jonny Banger – not his real name – the brand is best known for its streetwear, emblazoned with cheeky, subversive graphics, often with a political bent.

Turner Prize-winning artist Jeremy Deller was among the crowd, as models walked in tracksuits from Banger’s recent collaboration with English sportswear label Slazenger and day-glo pink patent raincoats. The most memorable look, however, the one that saw Deller and just about everyone else reach for their phone, was a man inside a yellow boiler suit bearing a comically large ecstasy tablet, stamped with the logo of Japanese car manufacturer Mitsubishi. For those that knew, this was a nod to the popular tablets that first flooded British nightclubs in the late 1990s. In a similar homage for Spring/Summer ‘16, British skateboard brand Palace released a t-shirt boasting a similar illustration with the slogan “Putting the E in Palace.”

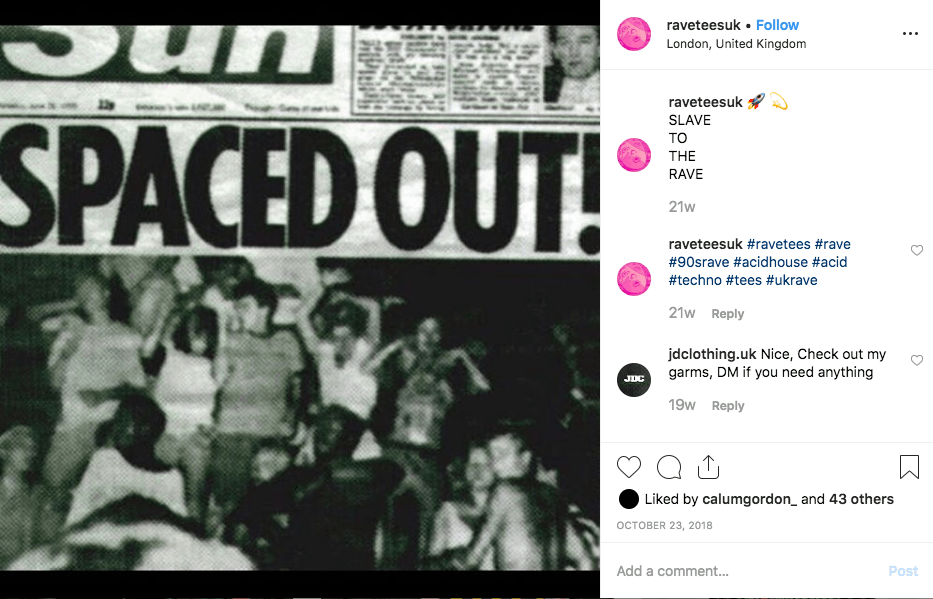

Earlier the same day, back on the official London Fashion Week schedule, Italian designer Riccardo Tisci, who has recalled his teenage club-kid days in 1990s London in multiple interviews, dedicated his new show to the concept of “youth.” It’s hardly a groundbreaking subject in the realm of fashion, but what was notable was the show’s soundtrack, overlaid with audio excerpts from the era when he first arrived in London as a fresh-faced 17 year old. As the models began to walk, the voice of newsreaders sliced through the music, stirring moral panic about pilled-up ravers flocking to warehouses and abandoned fields on the outskirts of towns and cities for one-night-only parties.

References to late nights and chemically-induced collectivism have been woven throughout recent fashion history. Much of the German label GmbH’s aesthetic is built around this sort of weekend hedonism, and 032c’s own label presented its first women’s Ready-to-Wear collection late last year in London, also nodding to its designer, Maria Koch’s, clubbing days. But this particular strain of rave, from impromptu warehouse get-togethers in the late 80s and early 90s, through to the more illicit happenings later in the decade fueled by Doves and Mitsubishis, seems to have been absorbed into fashion’s current lingua franca. Earlier this year, Jeremy Deller presented his latest film at Frieze – a documentary on acid house titled “Everybody in The Place,” sponsored by Gucci. In July of last year, Gucci launched another film as a sort of prelude, a near-facsimile 1989 night out, backdropped by London’s rave scene. A similar film was released by adidas’ Spezial line in December 2018, documenting the 30th anniversary of the north of England’s “Acid Winter.”

The interesting question to pose isn’t why fashion has always mined counterculture for inspiration, but why now?

There are political parallels, particularly in the UK. The recent decision to jail two prominent rappers, Skengdo and AM, for performing their drill song “Attempted 1.0” at a London concert last December echoed the 1995 Criminal Justice Act which sought to stamp out illegal raves, giving police the power to shut down events playing music “characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.” The protracted neoliberal onslaught of the late 2000s and 2010s, which saw public services hollowed out by austerity, precipitated the political backlash of 2016’s Brexit vote by those that felt disenfranchised and disenchanted by the UK’s political system. In the late 1980s, after a decade of Thatcherism, a similar feeling of helplessness and political ennui sparked the first wave of self-induced euphoria as a means of temporary escape.

“I think whenever there is political instability and the youth are living in a climate where it’s near impossible to see any hope in the future, movements like rave are hyper-important,” says Louis Simonon, who runs @Raveteesuk, a brand that sells t-shirts emblazoned with old 90s rave flyers through Instagram. “It’s a release. It’s rebel music. It’s exactly the same as punk or dub to me in that way. [Rave culture] is a kick back against what we are told to be and how we are told to behave.”

The idea of rave as a response to the politics of our time is not simply a grandiose misreading. In recent years, theorists including Matt Phull and Mark Fisher have explored the notion that subcultures, such as rave, could be a key element in consciousness raising on the left. Fisher’s work on “Acid Communism” is, sadly, incomplete, following his death in 2017, but the name alone seems to deliberately invoke acid house and, in turn, what Fisher believed was the very best the UK has previously had to offer – creative, working class subcultures, capable of moving art, culture and politics.

Acid, as used by Fisher here, is an abstract concept, loosely conceptualized as a means of invigorating the countercultural spirit of the 60s and 70s, and a viable alternative to “capitalist realism,” which Fisher defines as our collective inability to imagine a world not governed by capitalism. As argued by his British anti-capitalist colleagues at PLAN C, this would function in the same way The Beatles’ experiments with LSD led to a new approach for the band that, in turn, permeated mainstream culture. The Beatles’ output of that era “embed[ed] a notion of a plastic and changeable reality,” they write. “We can think of psychedelia as containing the potential to expand social and political possibility because it undermines those elements of life that are presented as necessary and inevitable by revealing them as merely contingent and therefore, at least in principle, as changeable.”

Early rave was one of the few subcultures to emerge in the UK’s major cities and to simultaneously exist outside of them, connecting kids from the metropolis with those from smaller towns and the suburbs. That’s rare for subcultures, so often set against grey concrete backdrops. As cities like London today become playgrounds for oligarchs and estate agents, awash with identikit coffee shops and hot-desking spaces, the working classes are pushed further and further away from the center. According to the London Mayor’s office in 2016, the previous five years saw 50 percent of the UK capital’s nightclubs close. An escape to the country might be just the antidote to that.

Writing in The Face in 1991, as part of a piece about how acid house killed the football casual subculture of the 80s with rival hooligans hugging it out in fields, Gavin Hills mused on the scene’s future: “The most obvious thing to happen is that the rave scene will get the ‘Swinging Sixties’ sanitisation treatment. Our kids will be collecting the Panini ‘Great Pitch Invasions of the Eighties’ sticker collection. They’ll send off to K-Tel for a video CD of ‘Those Smiling Lucozade Days.’ We’ll develop false memories and start spinning tales.”

Perhaps that’s what’s happening here: an anodyne homage, a collective bump of that most seductive drug – nostalgia. As ever, when fashion brands – particularly those which are well-oiled, profit-extracting machines catering solely to an elite clientele – seize upon a particular subculture, even one that emerged a long time ago, people get protective. “I can’t really say whether or not I think that’s a good or a bad thing as I’m glad it’s being celebrated,” says Simonon. “But I think the DIY and underground ethos is something that needs to be carefully preserved. It would be awful if it was bastardised by some massive fashion house or something.”

There’s a potential dichotomy in this rave revival. Brits are gluttons for nostalgia and the collective passion for a past that never existed is a trait as British as queueing. But perhaps it’s something more, some sort of intangible shift. Fashion doesn’t exist in a bubble – much as it might try. Culture and political feeling seeps in. Right now, as the UK scrambles for something resembling hope, maybe this is an unconscious backlash, as subcultures have so often been in the past, to a lack of time, a lack of real freedom, to a system that’s saddled citizens with debt and an enclosed 48 hours at the weekend during which to forget it all. Make no mistake, this is not a rupture or a revolution, as so many things are framed in fashion, merely a temperature reading. However, that a 44-year-old Italian designer who spent his youth in the clubs of London, and a young, left-wing streetwear bootlegger (cheered on by a Turner Prize-winning artist) seem to feel the same way speaks to not only the unifying spirit of rave, but also its power as a means of moving culture, and dragging politics along with it.

Credits

- Text: Calum Gordon