Come Tees Meets R. Crumb

|SHANE ANDERSON

While trying to settle on a name for her streetwear brand in the making, Sonya Sombreuil showed her brother a list of 100 ideas. “Call it anything but Come Tees” was his answer, which sparked Sombreuil to do exactly what he advised against.

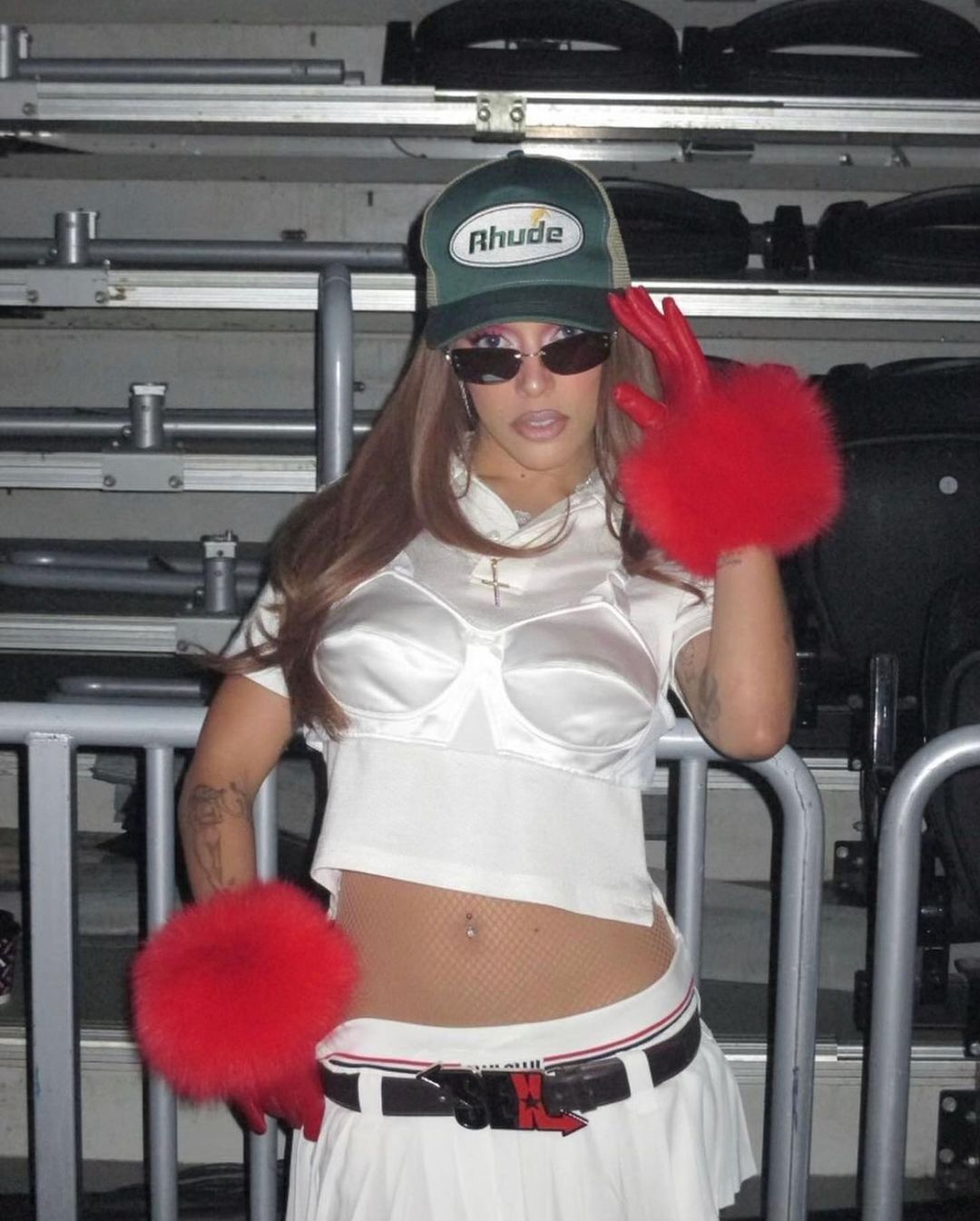

“It hit a nerve,” the painter and entrepreneur says, noting that she didn’t really think about its potential sexual connotation at first; she just liked the name “because it was cute.” Founded in 2010, Come Tees was originally imagined as a small label to create merch for her community of punk friends, but it soon reached much wider circles. The brand started being carried by many upscale stores and stars like Rihanna, Rosalía, Lil Nas X, and Tremaine Emory wearing her clothes. Collaborations with Comme de Garçons, Converse, Eckhaus Latta, Heaven, Supreme, and others followed.

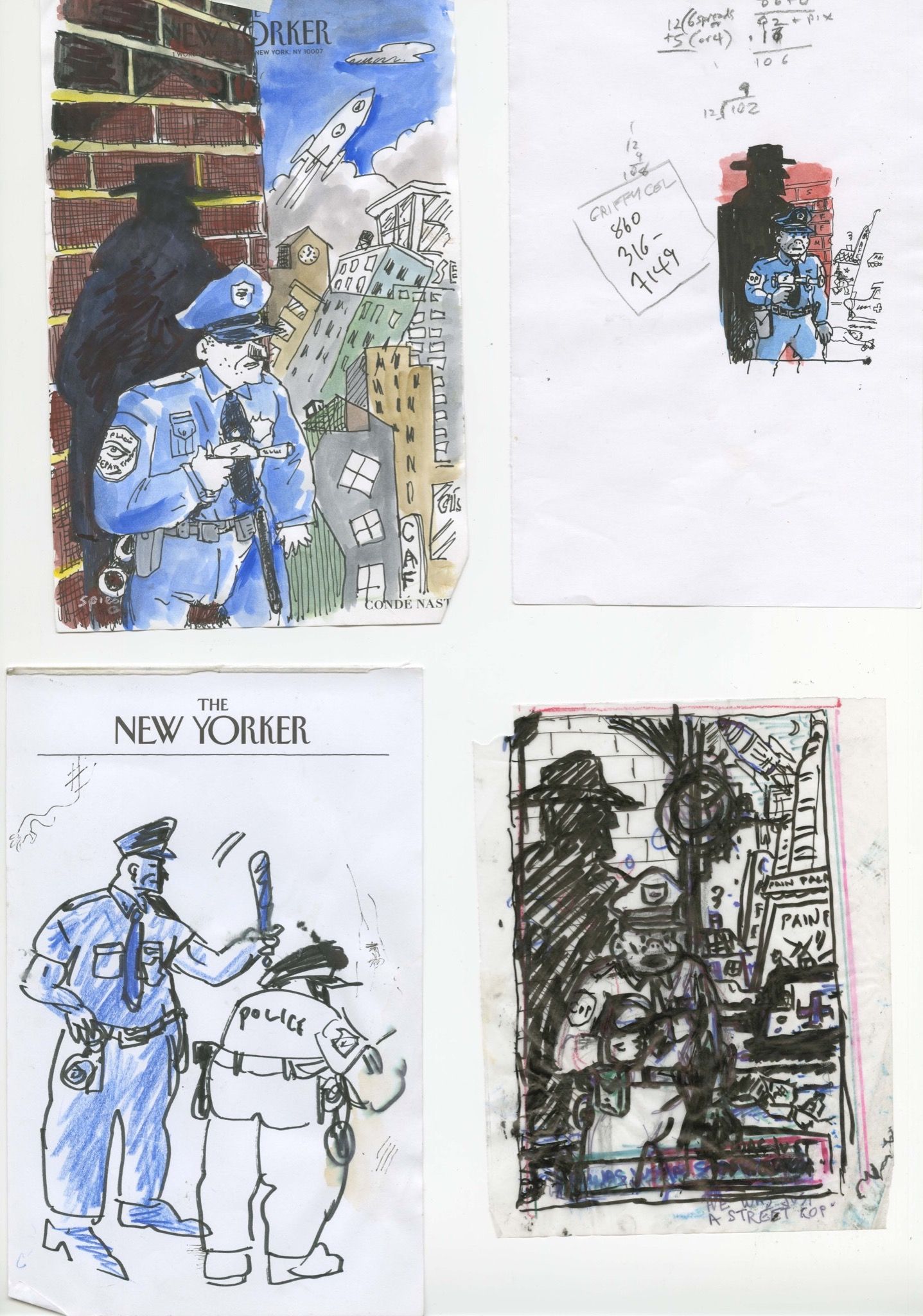

In conversation, Sombreuil suggests that Come Tees often “dances on the line” of unacceptability, which is on full display in her new collection Comes Tees x Crumb, released on the occasion of Dan Nadel’s new biography Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life (2025). The t-shirts feature somewhat lewd drawings by the legendary comix artist R. Crumb as well as illustrations from some of his most-famous strips like Fritz the Cat and Mr. Natural. In the 1960s and 70s, Crumb reimagined comics and cartoons as countercultural artforms capable of addressing the problems of the era while also delving deep into his own pathologies. Today, his depictions of women are highly controversial, with some calling for him to be cancelled, yet it is exactly these themes that Come Tees works with as it fits Sombreuil’s own ethos of line dancing.

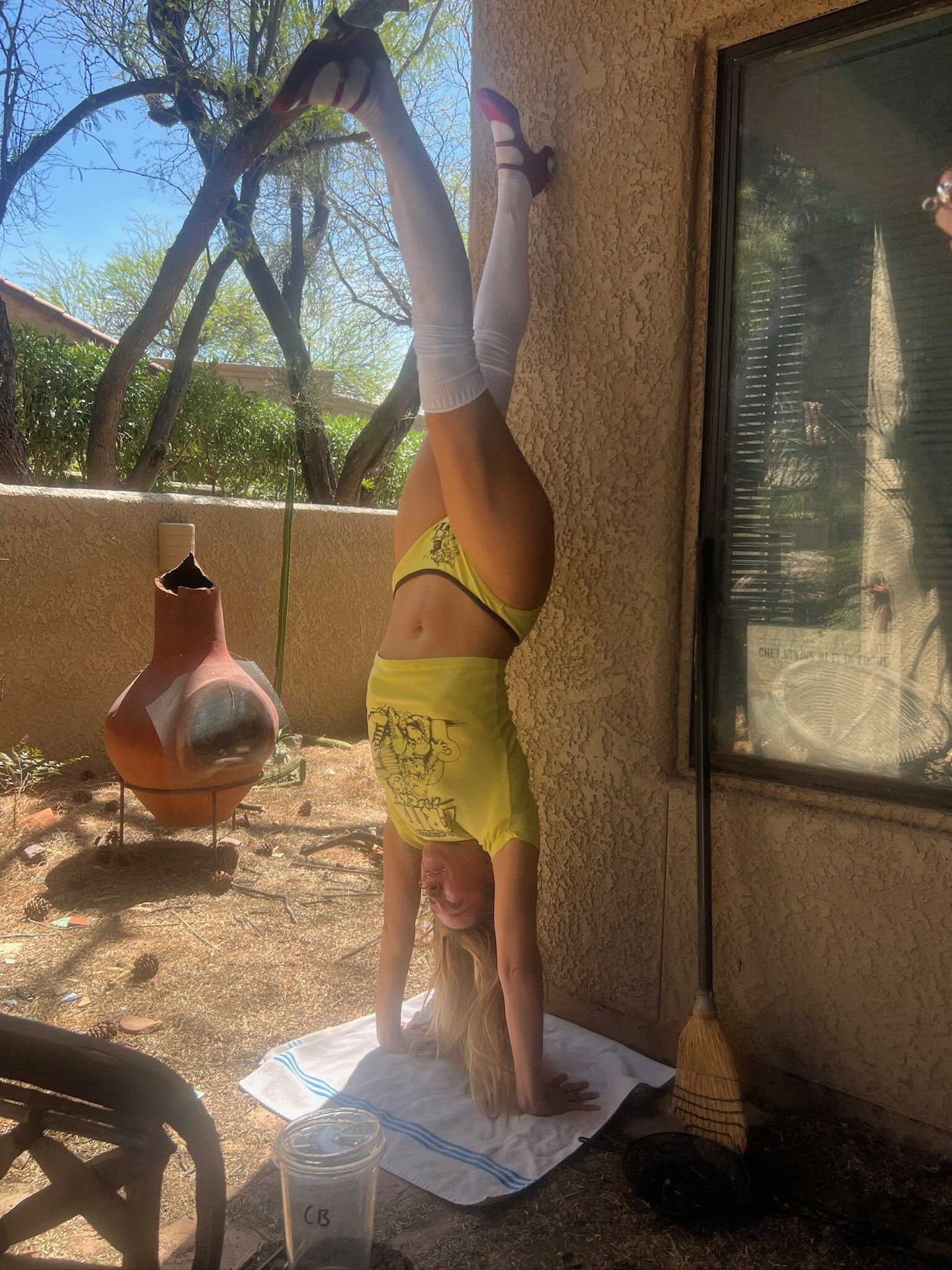

As such, working with Eric Kroll for the collection’s campaign was a perfect fit for Sombreuil. Although Kroll worked as a photojournalist in New York of the 70s and 80s, he is best known for his fetish images. Shane Anderson spoke to Sombreuil about punk aesthetics, working with two old perverts, and the dark depths of the collective unconscious.

SHANE ANDERSON: Tell me the origin story of Come Tees.

SONYA SOMBREUIL: I started the brand because I had just graduated college with a degree in painting in 2008 and the economic situation was really bad, so painting didn’t seem viable. At the time, I was interested in the primacy of my social life and always had a proximity to underground music. I wanted to make something relevant for my friends, something they could circulate, and it seemed to me that a painting show would have much less impact on them than making merch. I really wanted to participate in the world I cared about, which was punk.

SA: Come Tee’s aesthetics often lean into punk, right? But there’s also something else there.

SS: Yeah. I mean, I have a knee-jerk reaction to aesthetic mandates. I’m not the first person to observe that punk has one of the most conformist styles associated with it, and I’m not into that. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to love the really narrow, very pure anarchist or crust aesthetic, but I was more into fantasy and didn’t want to wear the same the patches on my pants like everyone else in the crust scene. On top of that, I feel like I have generational dysmorphia. I grew up immersed in my parents’ hippie culture and I didn’t really connect with things of my own time.

SA: So, hippie culture is an influence?

SS: To me, hippie is punk and punk is hippie. I inherited 60s and 70s counterculture and had some sort of over identification with it. That’s why I always loved R. Crumb. I have a pretty vast collection of his work. Whenever people found some R. Crumb piece, they’d give it to me because they knew I was into it. There are only a few artists in your life that you have a life-long relationship with.

SA: Is Crumb punk?

SS: He would hate that. The problem is that punk is undefinable. As soon as you define punk, it self-destructs. But in my approximation of punk, Crumb totally is because he’s opposed to being punk—which is really punk. In my view, punk is about impugning reality. And you can’t stay in that place or it stops. So, I think he’s punk in that sense. And I think he’s also very punk since he’s into music that nobody thinks is cool. There are all these statements about how much he hated the Grateful Dead and long-haired hippies and never wanted to fit in with them. He’s also a prodigious 78 collector of calypso music, which is so great. I mean, in a time when almost every single subculture and genre has been subsumed into being cool in a mainstream sense, calypso—

SA: Bad Bunny would like to have a word with you.

[Laughter]

SS: True. Bad Bunny is super cool though. And the name Bad Bunny is kind of like R. Crumb.

SA: Why did you decide to do R. Crumb t-shirts after fifteen years?

SS: I was approached by his biographer Dan Nadel, who has been working closely with Crumb for the last eight years or so.

SA: How did you make your selections?

SS: It was really difficult because he has these images that are truly iconic and almost ubiquitous. They’ve been bootlegged at such a high volume so I wasn’t sure if I should pay homage to something that was already culturally resonant or if I should somehow reflect on his entire career, which has changed a lot over the decades. He used to draw these psychedelic acid drawings but then you can see he matured in life and his subject matter changed. He also used to draw women, which he no longer does, and the style also changed. I mean, he even drew The Book of Genesis (2009). I felt torn between these different responsibilities. I’ve never done any kind of artistic collaboration—all of Come Tees is my work. But then, one of my best friends, Jessi Reaves, told me that I should just do whatever I liked, which sounds obvious, but was totally liberating. So, I just thought of the different comics that were in my head and they all happened to be these truly comical and benign characters of women. I really like the lewdness and obscenity. There’s a lot of rage, perversion, and discontent in Crumb’s work but there’s also a lot of love and humor.

Humor is contingent on stigmas. Crumb isn’t denigrating these stigmas as much as enforcing that they exist. The point of his work is to make you feel uncomfortable.

SA: Why is such lewdness something you wanted to work with?

SS: I play with eroticism in my work in general and I’m interested in female lead characters. Crumb’s drawings of women always resonated with me. There’s this paradox there. He’s accused of the worst kind of objectification but I always loved his drawings of women because they were big and muscular and didn’t fit in with the actual cruelty towards women, which has to do with them having to be really thin or proportionate. There’s something demonstrative and loving about drawing big women. Obviously, it doesn’t resonate with everybody, but from an early age, I really identified with him as an eternal outsider. And I identified with his subjects—these interesting, goofy women. All the things I chose are playful. They’re funny. Some of them are recognizable, like Fritz and Mr. Natural. But I also included Teenage Pigeon Girl, whom I love.

SA: What is it that you find funny about Fritz?

SS: I think Fritz is funny because of his arc. He’s this disgusting guy who’s murdered by a woman because he won’t have sex with her. In another story, he saves Teenage Pigeon Girl from being sexually assaulted by the police. He takes her back to his place and then eats her. After all, he’s a cat and she’s a bird and that’s just what cats do.

SA: That’s so dark.

SS: Crumb used to say that too. He would say that he doesn’t know where this stuff comes from but that it’s from something collective and very dark. There are so many different forces acting on the psyche and artists are often extremely sensitive to invisible forces. To me, Crumb’s a wounded healer who illuminates his own psychological pathologies on behalf of the entire society. There’s this great quote from the Gospel of Thomas where Jesus says, “If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.” He’s taken his contempt, fears, perversions, and everything he is ashamed about, and put it in the light and exposed what’s really shameful about the American psyche, which is violence and cruelty. Obviously, some of his work is offensive and I don’t want to be in a position to defend it, but I think the body of work is important right now. I have a great love and passion for the fact that humans are super complicated and messy. To error is to be human and to be human is to error.

Also, humor is contingent on stigmas. I think it’s very important cultural work to challenge or even address cultural taboos—after all, Crumb isn’t denigrating these stigmas as much as enforcing that they exist. The point of his work is to make you feel uncomfortable. Nevertheless, if you look at the imprint R. Crumb has made on culture, you’d see that he is a very ethical person and notoriously upstanding. It’s also funny how we choose who we want to see cancelled and crucified and those we want to save. But somehow the pathos of someone like Crumb is really resonant with me.

SA: Does the work of Eric Kroll resonate with you in the same way?

SS: It’s like my private fixation. I have bought a bunch of his work on eBay. I reached out to him years ago to see if he would shoot something for me and he responded, “I’m not interested. I don’t see how I fit in your world.” When this project came up, I really wanted him to shoot it. I could see it in my mind’s eye, so I approached him again. And he was like, “Oh yeah. I shot something for R. Crumb and I charged them a bunch of money.” He shot the cover for the documentary, which I had no idea about. It was like kismet.

He also totally understood the assignment. I knew that Kroll knew what a Crumb girl is. There are as many similarities as differences between his and Crumb’s work but there’s something about the tone that’s similar to me. They’re playful, fantastical, and intelligent—they’re not just sexualized women’s bodies. What I loved about these two perverted artists is that they definitely do not subject women to the quotidian cruelty inflicted upon women.

Two of my really close friends, Jessi Reaves and Flannery Silva, who are both artists, offered to model and we all went to Tucson. There were so many question marks: Who is this person? Why does he live in Tucson? Why is he such a prolific poster on Instagram? Is this going to be feasible? When we got to his house, we were all totally blown away. It was more incredible than I could have anticipated.

SA: What was he like?

SS: He’s amazing. Really fun but also mercurial. He has this quality that I couldn’t quite figure out at first. Then I realized that he’s personally fulfilled. He did what he wanted to do and he’s content. It feels really good to be around him. I kept saying to my friends that he OD’ed on beauty. There are beautiful photos of women—he has this unbelievable archive of pin-up and fetish photography, amongst other things—as well as beautiful women’s clothes and boots everywhere. He has like 30 cowboy hats in his bathtub. The house is beyond a museum. He knew everybody and has so many portraits of Downtown artists from the 70s. He had photos from this one very obscure, fetish photographer who took photos of women’s hair in public. Every drawer you open is completely filled with boxes of photos that are somewhat organized. Then there are stacks of photos a couple feet tall on every surface. You can only stand in the house. So, we had this whole education. It was really magical and such a fluid experience. He’d show us some erotic photographer and explain the importance of that person, then would pick up his phone and take a few pictures. The next day he took us thrift shopping. He just wanted to go from store to store.

SA: How long were you there?

SS: We were only in Tucson for less than 72 hours and we shot the campaign in one day. I haven’t really talked about this, but he really wanted to shoot with his iPhone. I really wanted him to shoot on film since I love his film photography. In the negotiations, he would say “yes,” then a couple of weeks later, he’d say, “I don’t think I’m your guy. If you care about an artist, you have to let the artist shoot with what they’re comfortable with and I only like shooting on my iPhone.” My friends were like, “Don’t let him shoot on his iPhone, we’re going to look terrible in the pictures.” When we got there, I arrived with all these fancy cameras he had whimsically requested, but he only shot on his phone. I was having a small crisis, thinking, “Oh my God, now I have to shoot backup stuff.” I will say this though: the more I looked at his selection, the more I was like it’s very him and very special. I showed him the pictures I took as a backup and he was like, “These suck. Good thing you hired me.”

SA: What makes his photos so good?

SS: Good question. I think it’s because he really understood the second when things crystallized into a moment. I have like 30 photos of the same subject where he took maybe one or two. His just have the whole vibe. Another thing I realized is that he really loves action. He kept saying, “Now, floss your teeth!” or “Open the fridge door! Go in there!” It was very cinematic and not the typical kind of still modeling. It was also very absurd.

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON

- Photography: ERIC KROLL

Related Content

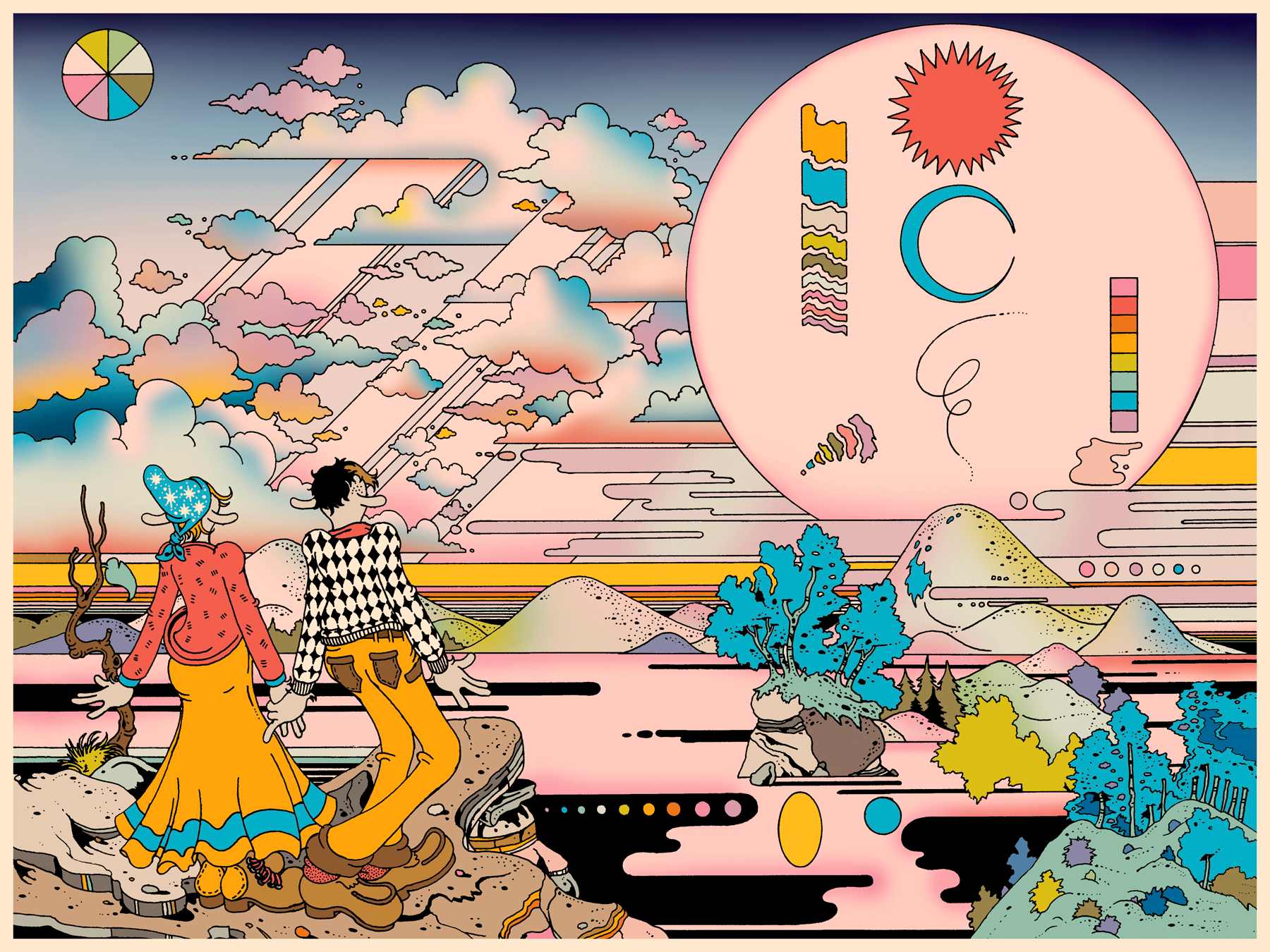

Despair and Dystopia Next Door: ART SPIEGELMAN in conversation with HANS ULRICH OBRIST

Reinventing Mike Kelley

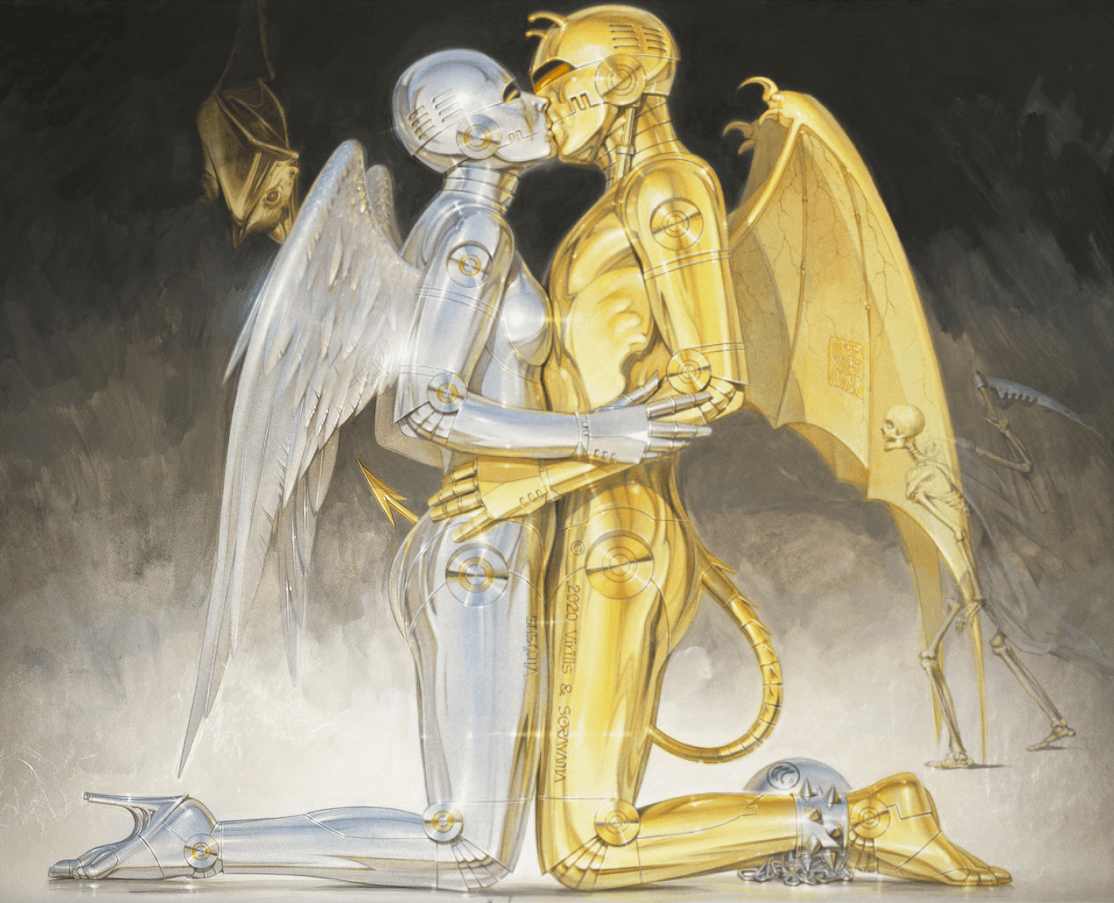

Hajime Sorayama: What I Draw Are Human Beings

Decolonize Your Trip

The Play-Doh Bunny: A History of Playboy

The Aggressive Attacker: An Interview with Chess Grandmaster Judit Polgár

The Erotics of the Nerd

Eckhaus Latta Prefers Glitches To Filters

Who the fuck is Vaquera?

The Metaphysics of SUPREME: Decoding Branded Objects with Philosopher Graham Harman

Taylor Swift Is A Virus

ABC of CdG