Taylor Swift Is A Virus

|SHANE ANDERSON

When artist and writer Heather McCalden’s parents died of AIDS, she was still very young. Now, she has written a genre-defying memoir that reckons with their loss in a series of fragments while also revealing some shocking discoveries about her father.

The Observable Universe, which is written in narrative vignettes, Wikipedia-like factoids, and aphoristic bits, is much more than just a personal story of trauma. It is also an extended meditation on viruses, the internet, crime fiction, Los Angeles, family, and metaphor. Mimicking the experience of searching for information on the internet where you jump from one subject to another and then back again, The Observable Universe uncovers the intersections between these themes and shows, for instance, what “going viral” on the internet has to do with AIDS, and why the internet might actually be alive. In this conversation with Shane Anderson, McCalden discusses grief and loss as universal concepts, the importance of self-preservation, and why Taylor Swift is a virus.

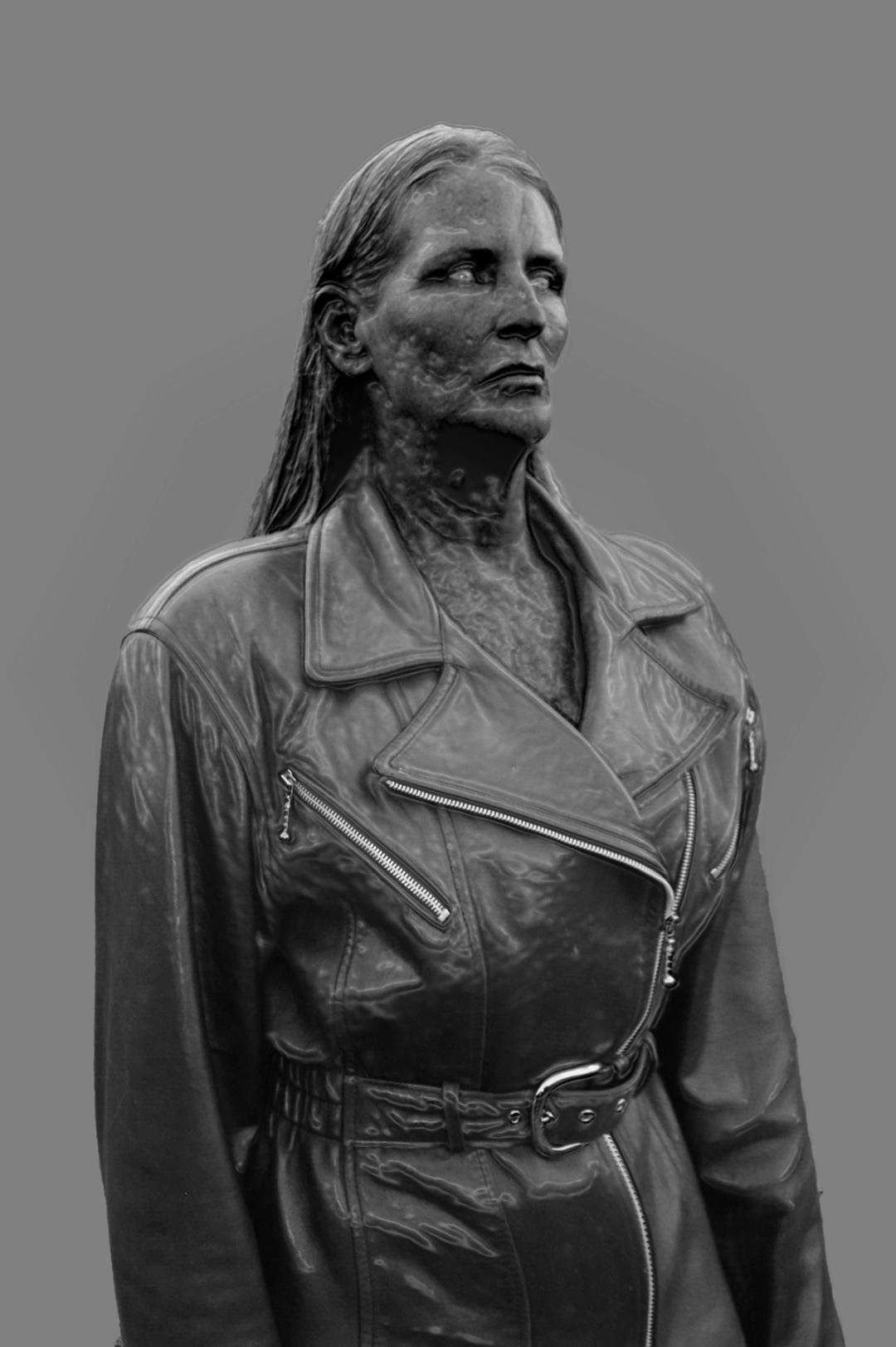

Two excerpts from The Observable Universe can also be read in 032c Issue #45, where McCalden’s words are paired with Petra Collins’ shoot of Rosalía.

SHANE ANDERSON: In The Observable Universe, you look closely at your trauma. I think it’s brave to open yourself to the world like that. What has the reader response been like? Have they opened themselves to you?

HEATHER MCCALDEN: I’ve had a bit of that. I was on the grief panel at the LA Times Festival of Books and a lot of people asked me, “How do you do life?” And I didn’t know what to tell them. I feel responsible to say something constructive but then… There’s this really great [Charles] Bukowski line where he talks about his phone ringing in the middle of the night. He says something like, people call me expecting I have all the answers, but my number’s listed in the phonebook precisely because I’m hoping someone will call me with all the answers.

SA: So, the book hasn’t given you any closure?

HM: It’s too soon to say. I feel like I won’t know what this chapter of my life means for probably another decade. People have asked me, “Has the book healed you?” but what they really want to know is if I still cry because my mom is dead. The answer is: yes, I’ll do that until I die. Nothing will change that. There are wounds that do not heal and the best thing we can do is use an art form to transmute the emotional debris they create into some beautiful or beguiling. That then becomes an object or energy that people can tune into and hopefully derive something positive from. I think the book shows that this type of growth is possible. It’s a type of healing, but it isn’t necessarily a personal one.

SA: At the beginning of the book, you have two epigraphs, one from the crime fiction writer Raymond Chandler and the other from Aristotle, which you amend with “at least according to the internet.” While these two quotes set the tone of the book very succinctly, what interests me is the way you bring uncertainty into the game from the very beginning.

HM: Yes, I wanted to highlight the fact that existence is not a certainty, and that grief is also a state of flux. It’s a state without grounding where the compass ceases to function. There’s also a recursive element in the book’s language that’s supposed to give you a sensation of this instability. Certain phrases repeat, but their meanings shift ever so slightly.

SA: The lack of certainty or being in an in between state runs throughout the book, such as when you look at viruses.

HM: Right. Our human understanding of viruses is partially characterized by what we do not know about them. In fact, what a virus even is gets frequently updated and reconceptualized depending on research advancement. But to be more general, knowledge and our relationship to it is mutating. The goal posts for what we classify as knowledge, and what constitutes mental processing keep shifting. Nothing is solid. Online we’re constantly interfacing with representations or portrayals of ideas, but rarely connecting to actual experiences or direct texts. What could be more unstable than that?

SA: Which brings us to metaphors, which are also unstable.

HM: We think metaphors are a very precise way to define what cannot be defined but they’re dependent on a person’s context, their spectrum of information, feelings, and experience, which is of course different for each of us. This is an inherently unstable configuration, and it leads us to hit walls in our search for specificity.

SA: In the book, you keep searching for specificity and clarity about your mother and father, but you keep reaching limits about what can be known. One thing that interested me is that you even imposed some of these limits. When you learned that your father was a right-wing extremist, you basically stop the search.

HM: Part of that is self-preservation. I guess part of my psyche or spirit knew that this would have overwhelmed my conscious existence, and I have to respect that. It’s valuable to understand that some things don’t need to be conquered, or rather, cannot be conquered.

SA: You talk about genetics and viruses in the book, and I was wondering if the interest in the former was because you inherited genes from your father and you were trying to reckon with that.

HM: Not really. I don’t think I’m a monster because I have a weird father and we share genetic information. My interest in genetics and viruses comes from the fact that we’re composed of code and we’ve created an entire universe composed of code and yet, we don’t know how to navigate this arrangement. It’s like we’re trying to mimic the mechanics of nature, but in doing so, we lose corporeality. The program malfunctions and we disembody ideas, our icons, everything just becomes information… Taylor Swift is basically a virus now, circulating through the air and permeating our thought streams. But what does it mean when a person becomes a viral cloud? Ultimately what viruses do, besides make us sick, is challenge our conception of what life is, so when “going viral” is the objective for so many people on this planet, we find ourselves in a bizarre existential crisis.

Also: no shade to Taylor. I think she’s a genius with the language of pop.

SA: According to the book, a virus is a hacker. You also suggest that it took new technology for us to finally be able to understand it. But since our language about viruses has changed over time, might it not be that the hacker metaphor will be dated in, say, 50 years?

HM: I think that’s totally possible, and it’s also how it should be. Our understanding of the biological world should evolve with time. When viruses were first discovered, we missed a lot of information about them because our assumptions literally rendered us blind. Like, we couldn’t see viruses in focus because our mental construct of pathogens, informed solely by bacteria, interfered with reality…

This is something that keeps me up at night. I keep wondering: What are we not seeing right now? What are we missing? What don’t we know? This is true in culture as well. Look at Cowboy Carter. I’m not sure we have the intellectual framework to discuss what this piece of work is yet, kind of like how we initially misunderstood viruses. I don’t think we’re evolved enough or see enough to have a fruitful discussion about how culture gets refracted through other types of culture and produces something new.

SA: But isn’t that just culture in general? Aren’t all artists influenced by others?

HM: Yes, but today the references are so dense and layered and also in conversation with each other – they’re coming from memes, Susan Sontag, what someone wore at the Met Gala, and whatever else, and it’s all in this huge tangle of self-awareness, history, and time. But we need a new language to talk about this interaction. We have the language for the individual parts, but not for the matrix of their forces, not for the tangle itself. I don’t know what the future discourse will look like, but I can’t wait for someone to dismantle it all and explain its mechanics, because I don’t want to read autofiction for the rest of my goddamn life.

SA: Do you think the interest in autofiction might come from us all growing up with reality TV?

HM: That’s a large part of it but it’s also the market that’s pushing it. I was talking to this bookseller who read a recent novel by an author whose name I won’t mention and after he got off work, he went home and read Moby Dick because he couldn’t handle another autofictional title. It’s an interesting choice, and I understand it on some level. We don’t have narratives, or novels, in the way we once did. Maybe we could blame the Kardashians for why no one is writing Moby Dick anymore, but I think it’s more complicated than that.

SA: It’s interesting that you bring up Moby Dick, which is supremely weird novel and has all these long sections on whaling and mythology interspersed in the narrative. In a way, your book reminds me of that. While ostensibly being about your grief and your attempt to learn more about your dead parents, there are countless detours on the history of the internet, Los Angeles, detective stories, metaphor, AIDS, and viruses.

HM: There are two reasons why the structure of the book is the way it is. First, I just think and write in fragments. That’s what trauma did to my brain. That’s what I can handle. And writing this was very difficult because I had 255 chunks of text, and I didn’t know how they would fit together. It was a huge gamble, but I somehow trusted that there would be a layer of connective tissue underneath that would eventually join them. And second: it’s a browser tab approach to experience. We explore day to day info on like 49 browser tabs. There might be an article I read that mentions a place I have never heard of before, so I look it up on Wiki, then go to Google Maps, and then I think, oh, I want to buy this skincare cream, but I can’t afford it, so I go to Reddit to see what the dupe is. As we zigzag between all these things it creates a certain foam. And I think that’s how people live right now, through this foam. I wanted to write into that, and it just so happens that my weakness, or what I consider my weakness, has a relationship to what’s going on, to how people currently experience information.

SA: At some point you ask whether the internet is sentient.

HM: If the internet is sentient, it won’t look like, or behave like, anything we’ve seen before, and as to whether or not it’s sentient now, well, it’s not, but I appreciate how it would be very appropriate to this weird moment we’re living in.

SA: What’s your take on recent developments in AI?

HM: I guess my answer is that I don’t know how to feel about it. It’s still changing and sorting out its shape. I’m not against it but I’m not excited about it either. In terms of art, it seems like it could push people further and deeper into their practices, but I don’t know if that’s a great benefit if it’s also going to fuck up healthcare coverage.

SA: Let’s go back to the beginning. The first fragment is an instruction for the reader on how to read the book and you talk about it being like an album and that the reader should have an experience. Was there a specific experience you were hoping the book would induce?

HM: I didn’t have a specific objective in mind. I just wanted it to feel like strolling through a photo exhibition. You walk by the first image and take it in and then move to the second image and take it in, but the experience of the exhibition is not found in any one of the images, it’s in the spaces between where you’re cognitively processing the narrative of your walk. In the case of my book, I wanted the reader to feel their mind working, piecing together these fragments and bits of information.

SA: So, in a way, the reader is the detective in the crime novel?

HM: Yes. That’s the pattern of cognition I wanted to instigate. I was definitely going for a marriage of form and content.

SA: But the reader isn’t only a detective trying to understand a whodunnit. At least for me, the book created a feeling of empathy. And I thought that was very interesting because even if the book mimics a browser tab approach, it didn’t generate this sense of being overwhelmed and distracted like the internet often induces.

HM: I address this in the book when I talk about how something different happens in your body when you’re absorbing information online versus in real life. There is a clear biochemical difference that kind of prohibits empathy through screens. As a writer, I’m not trying to induce empathy. I’m just trying really hard to explain what a thing is, and I’m limited in that I can only explain it through myself, which as a byproduct, tends to generate empathy in a reader.

SA: It’s like when you write, “We turn information into matter and exist through it.” But does that equally hold for loss?

HM: Yeah, and that’s why loss is so fucked up. Death is out of our dimension of experience, and so when something is lost, it shouldn’t feel heavy, right? It shouldn’t have mass because it’s something that’s vanished, atoms literally disappearing. And yet we feel a heaviness in that. We don’t really understand what this is, a disappearance of matter that has a paradoxical, very real material feeling attached to it. Every loss that happens to us, transforms us. They change our day-to-day interactions, how we eat, how we sleep.

I remember how at the beginning of Covid-19, there was this line in The New York Times about an elderly couple crying in their car in a grocery store parking lot because they were so afraid of catching the virus they were immobilized. I don’t know what happened to these people—but someone witnessed this event, wrote about it, and I read it—and now it’s a part of me. It will never not be part of me. It’s like a part of my spiritual DNA now. And we don’t have ways to really talk about how things like this, how tiny pieces of information we peripherally encounter, haunt us, infect us, and join our frames of reference. That’s what I meant by that sentence.

SA: Not to get too pop psychology here, but it’s interesting to me that even though we have so much information and are connected like never before, things feel lonelier than ever.

HM: It’s because we don’t have any way to talk about these experiences. I mean, you could pay a shrink 200 dollars an hour to share with her what I just told you about this haunting couple but that would be insane. I would never do that. I don’t think anyone should ever do that. At the same time, it’s like what I meant when I said that I lie awake at night thinking about all the things we don’t know. All of this is so new for the human experience. Maybe in 100 years we will have a way to talk about how the patchwork of information we absorb reconstructs us emotionally on a regular basis. Maybe we will be able to process and explain how a weird thing we read about changed us. I think once we have a way of sharing that doesn’t feel ridiculous—like posting on social media—we will all feel a lot less crazy.

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON

Related Products

Related Content

Home is a Place That Doesn't Exist Anymore: CHRISTOPER KULENDRAN THOMAS at the Schinkel Pavillon

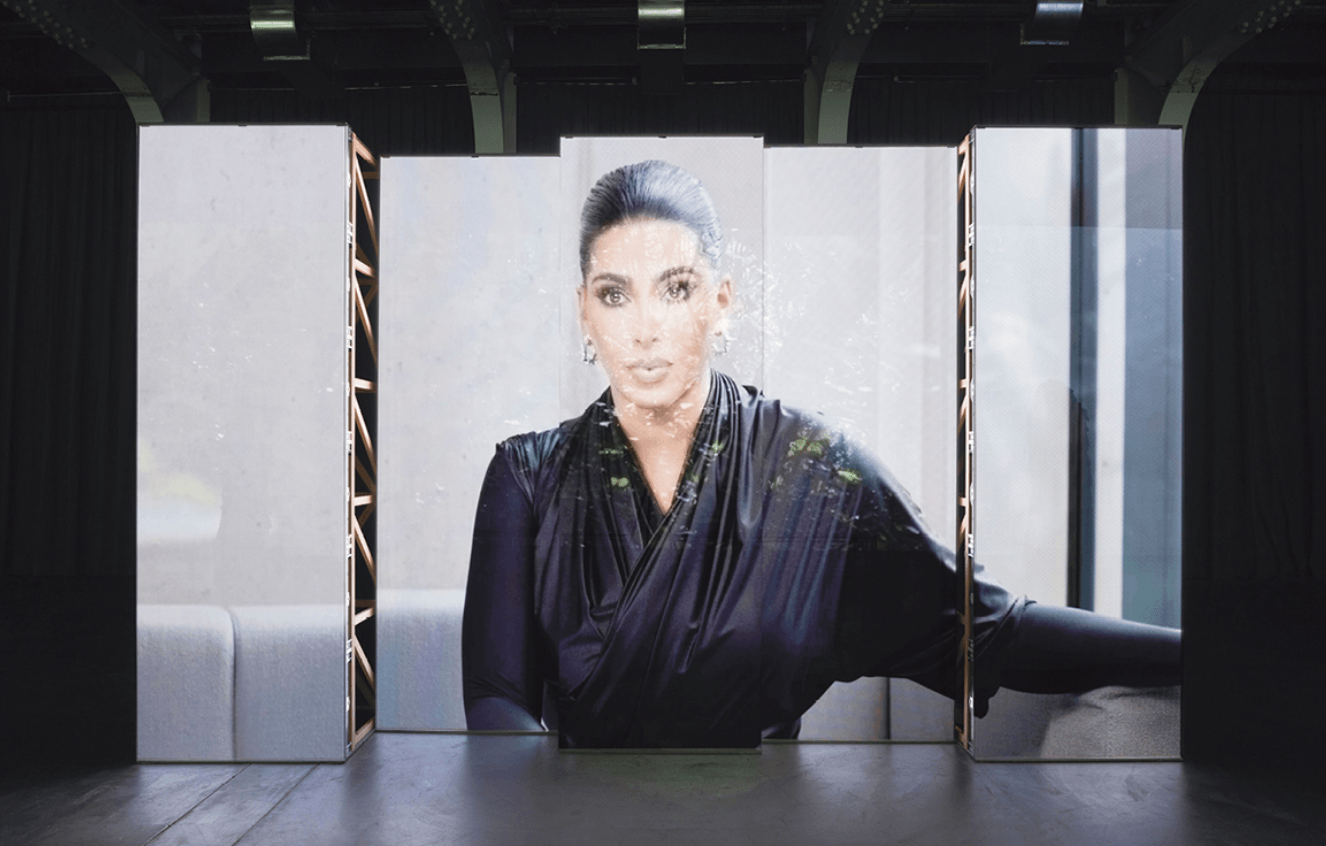

INVENTING KIM KARDASHIAN: CHRISTOPHER KULENDRAN THOMAS

Gross AI Spam with Cory Arcangel

Image Stacks With ISABELLE GRAW

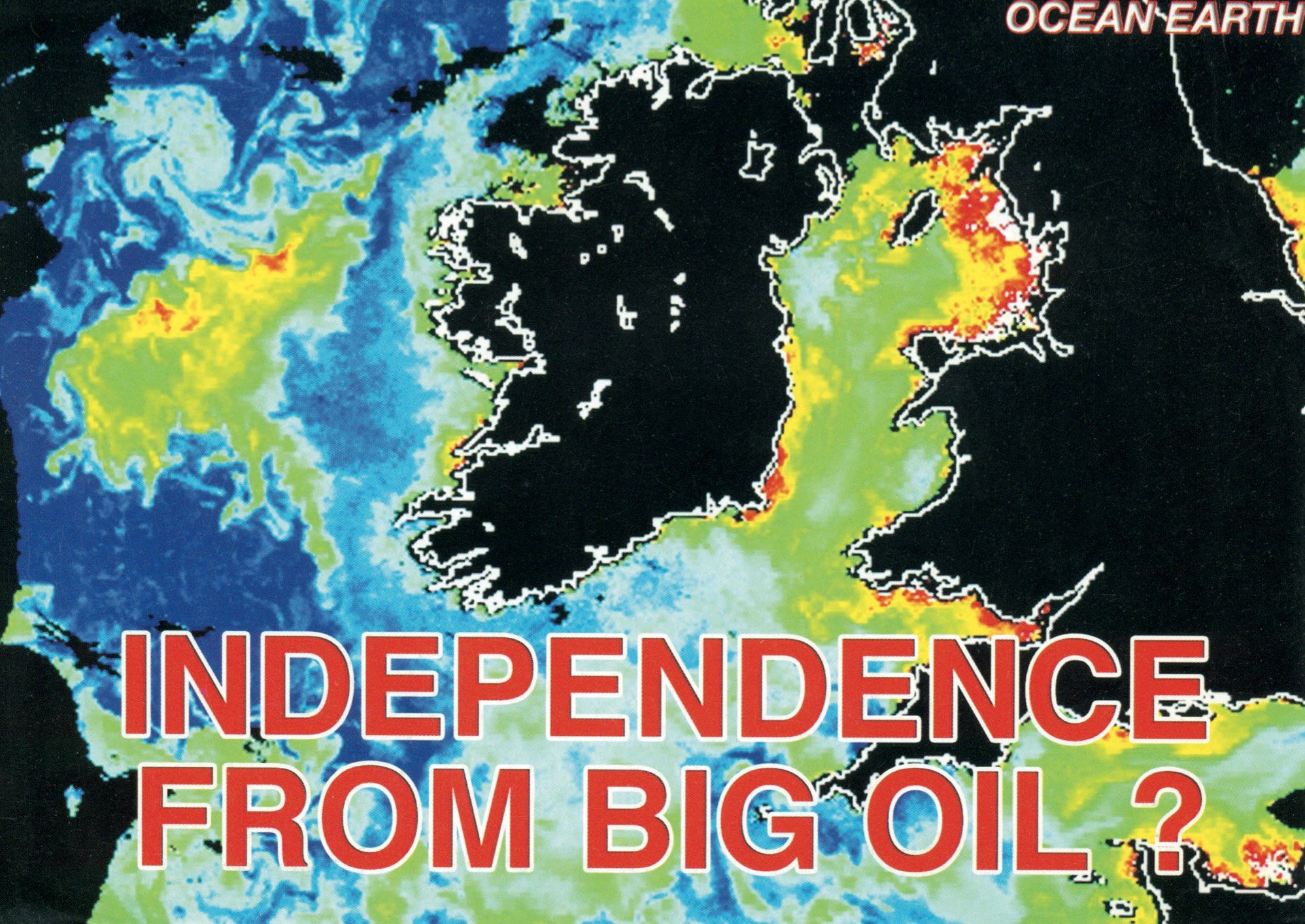

Artists as Messiahs: PETER FEND

The TRUMP-BALENCIAGA Complex

The World’s Biggest Gay Social Network Now Is a Publishing House, Too!

KRISTINA NAGEL’s Landscapes of Depersonalizations