Despair and Dystopia Next Door: ART SPIEGELMAN in conversation with HANS ULRICH OBRIST

|Hans Ulrich Obrist

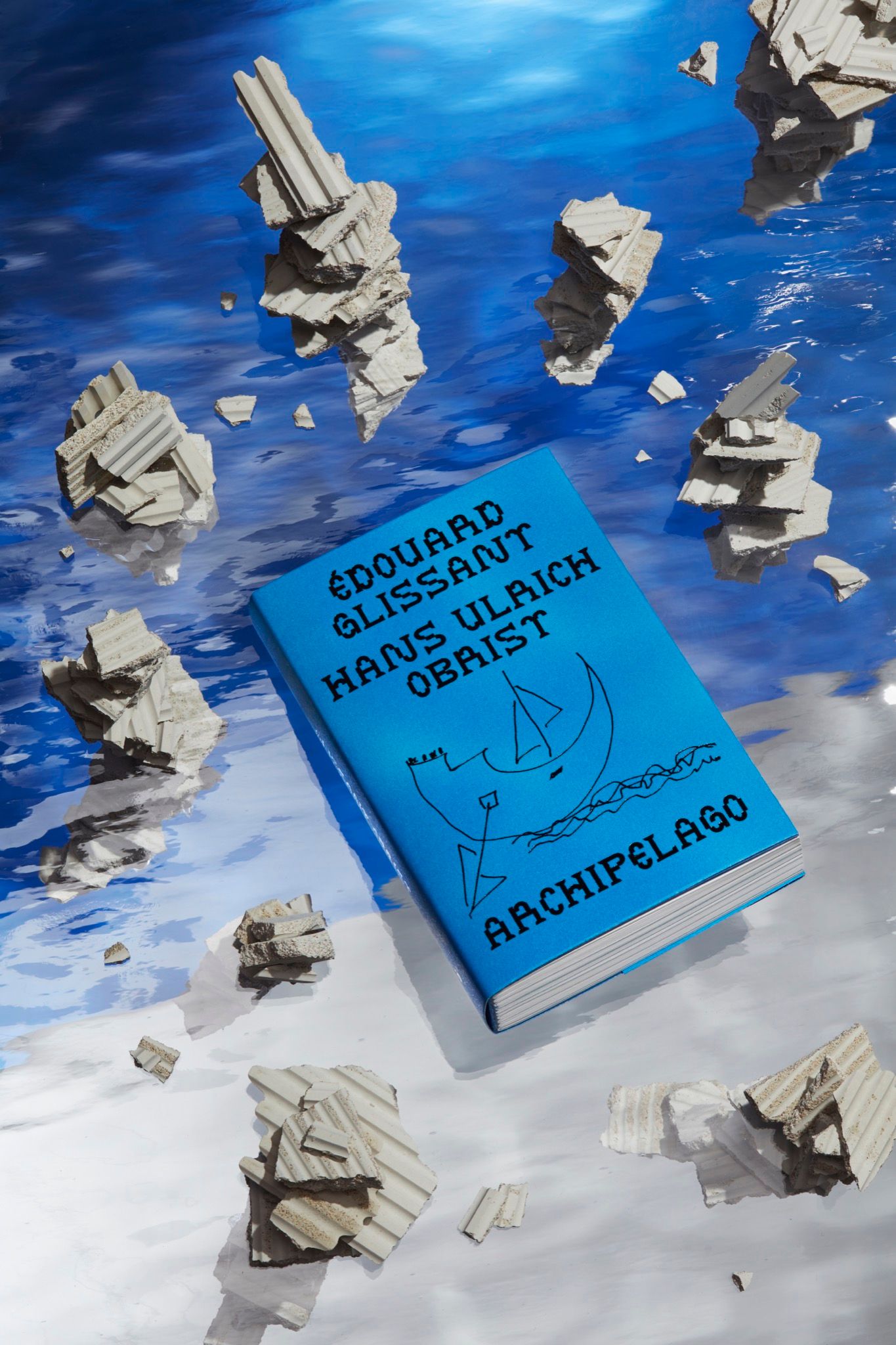

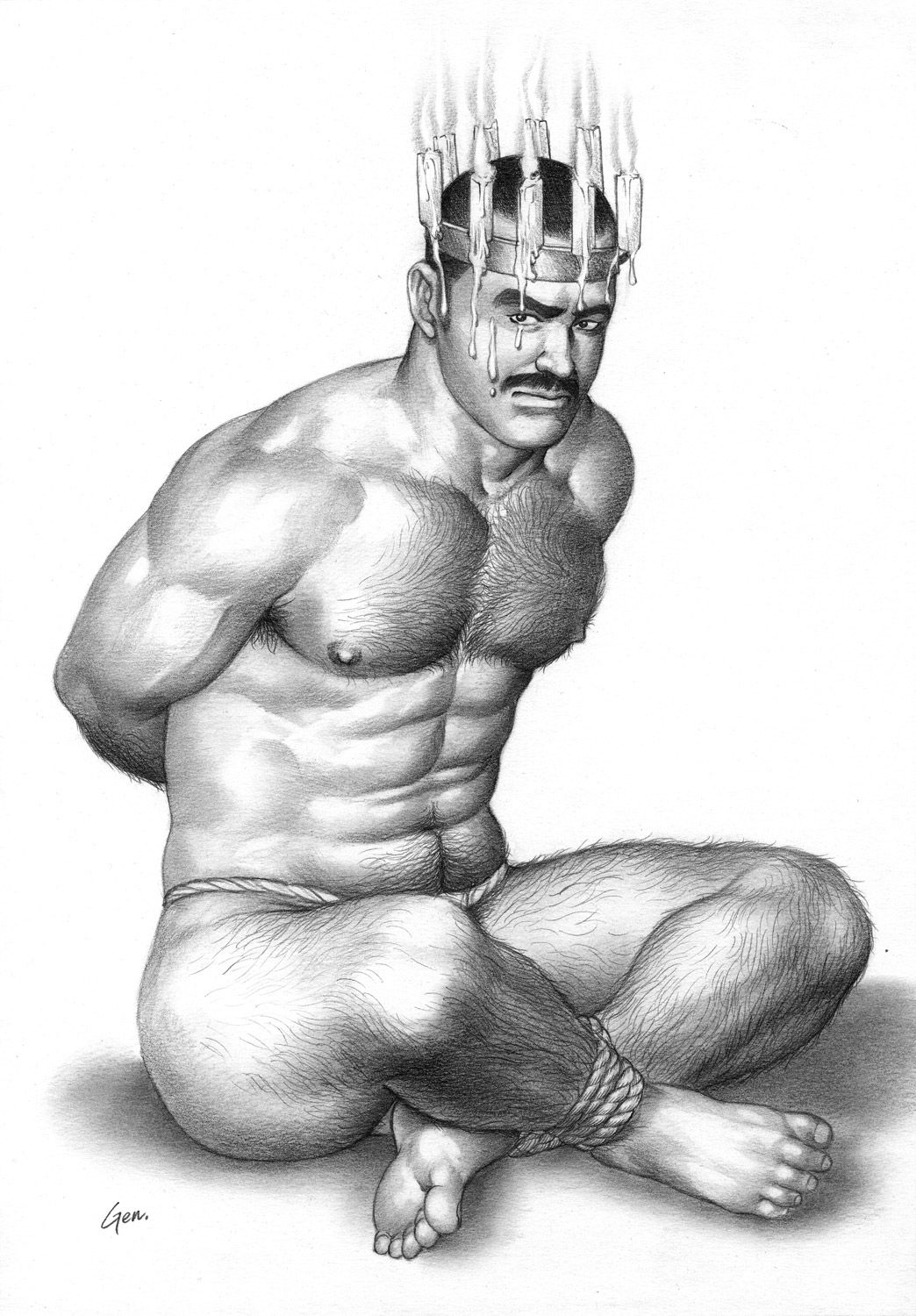

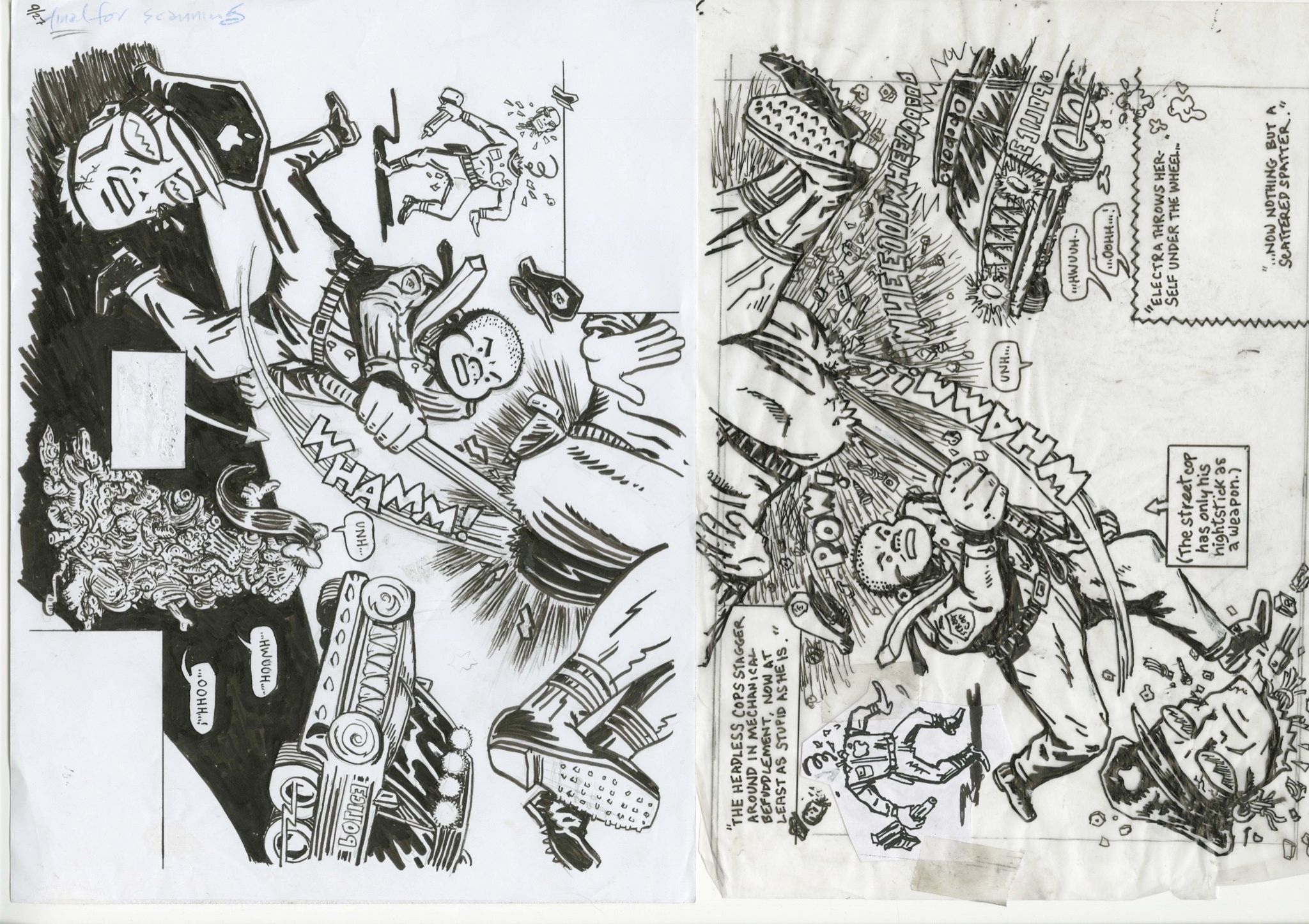

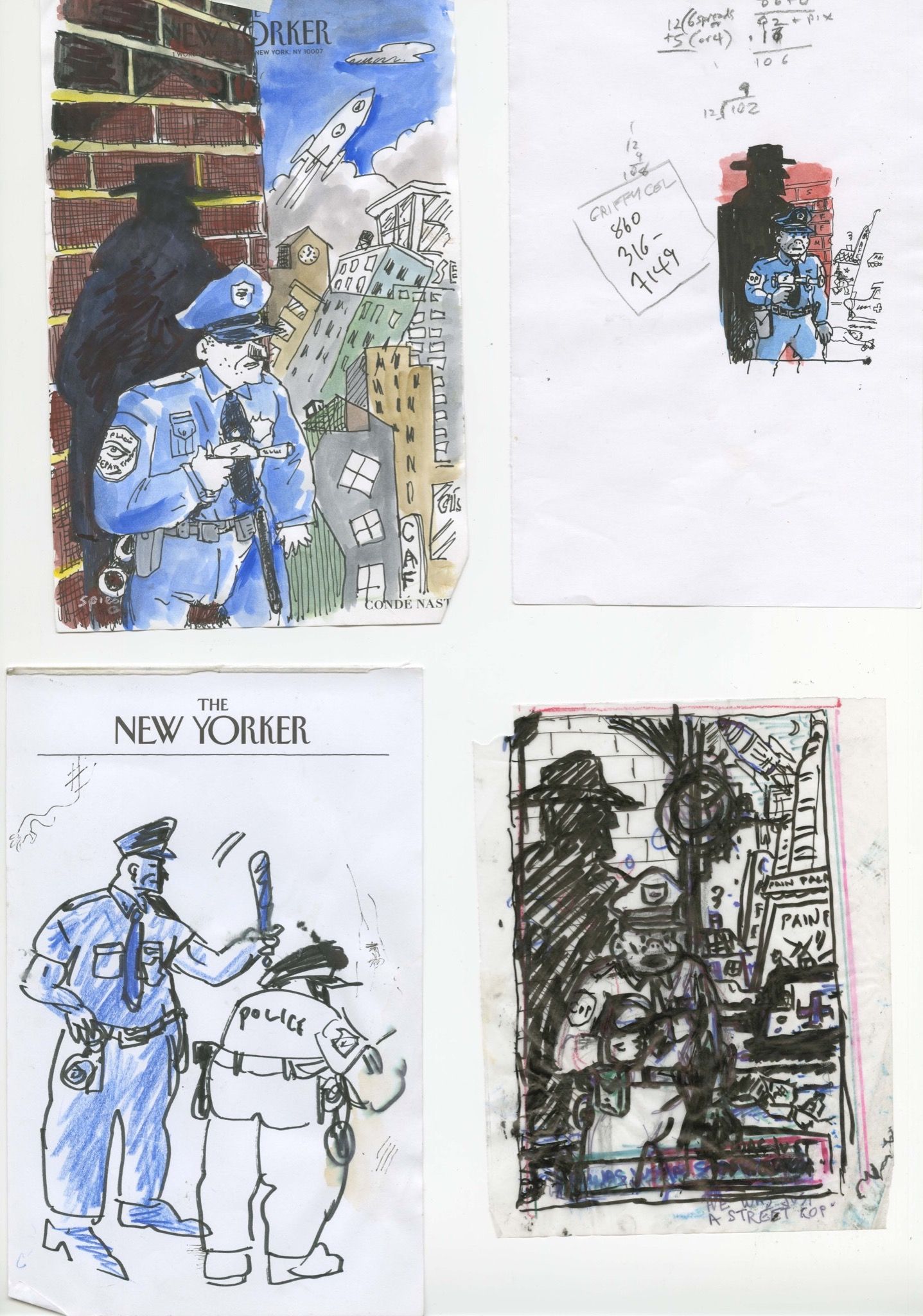

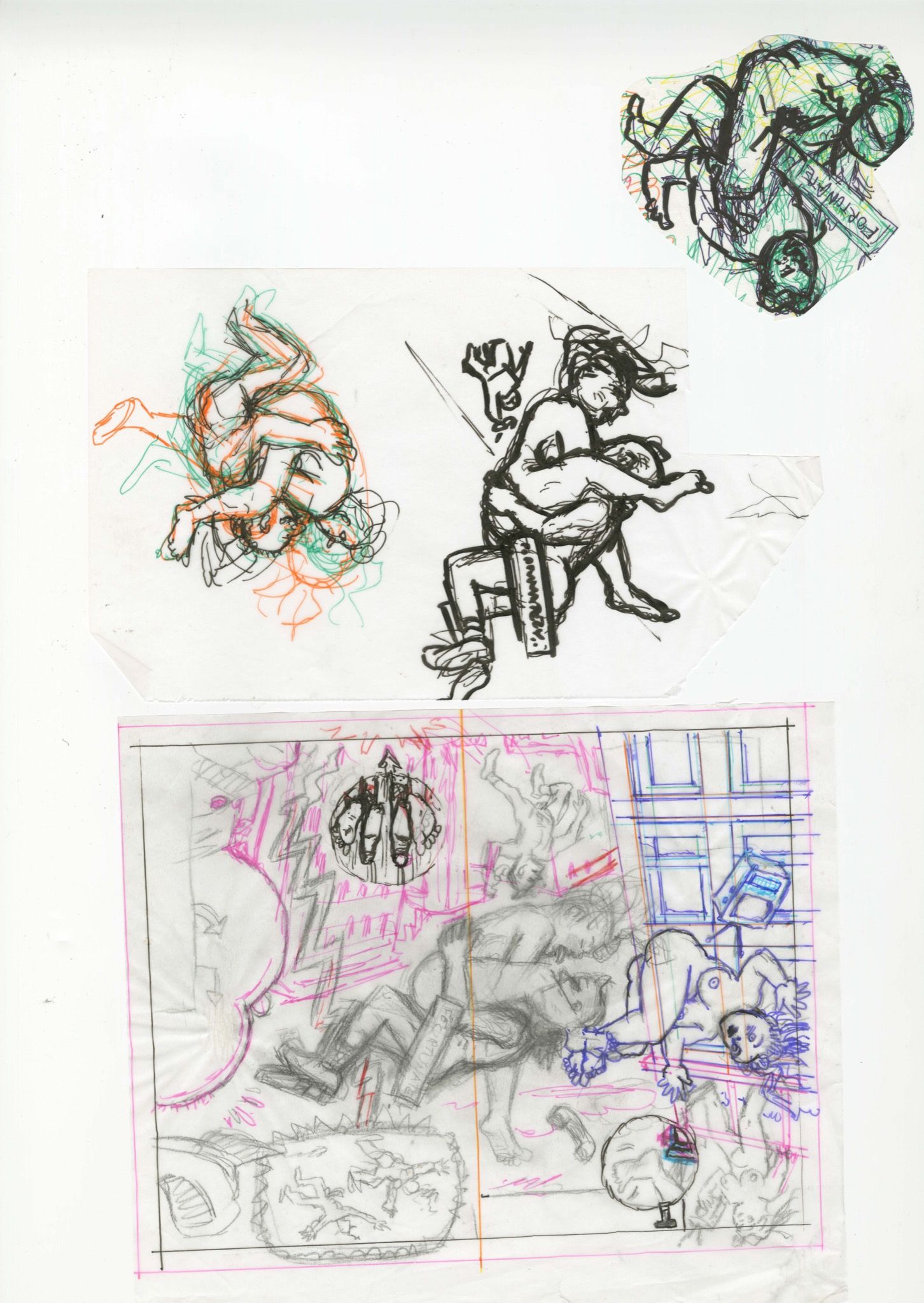

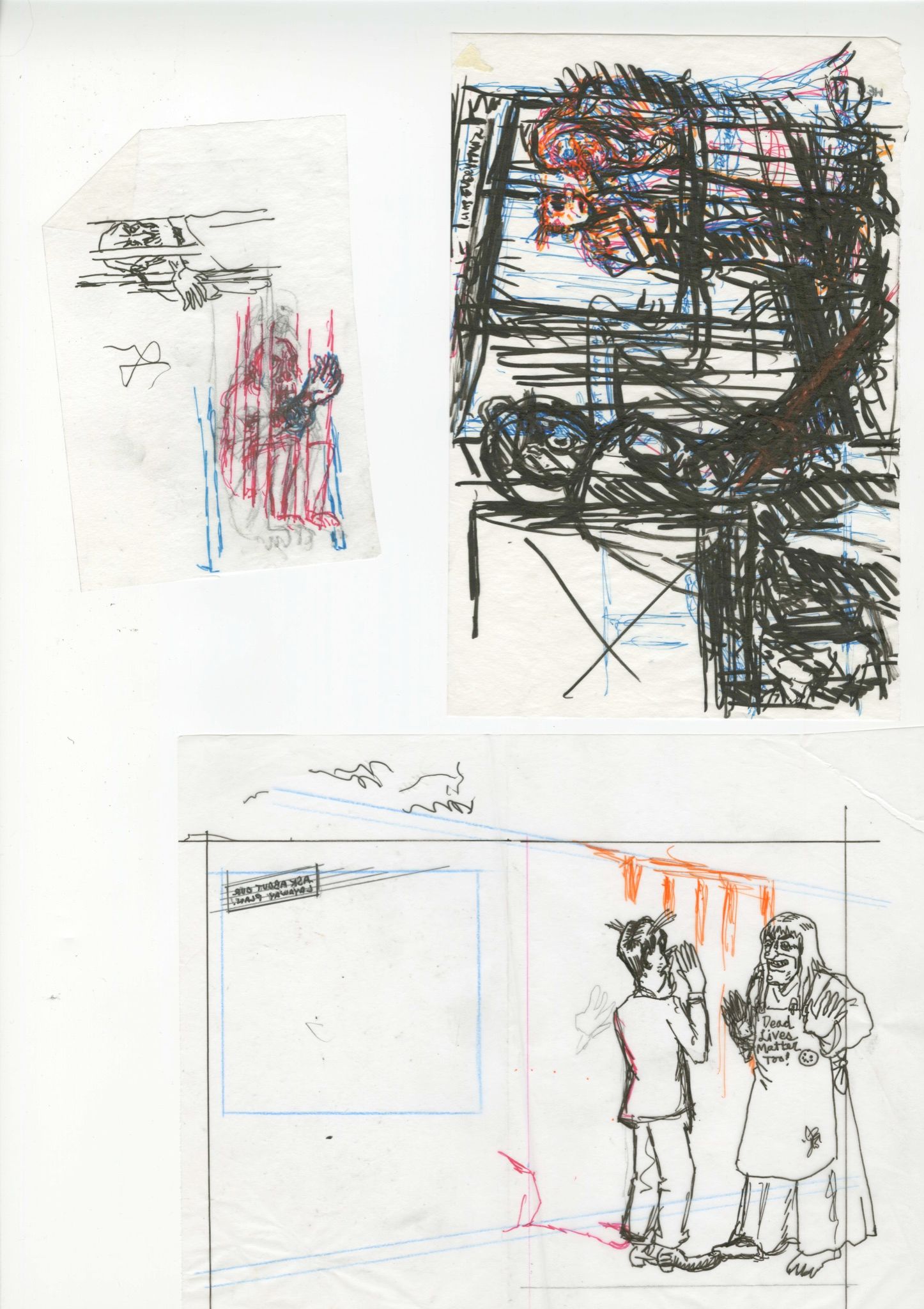

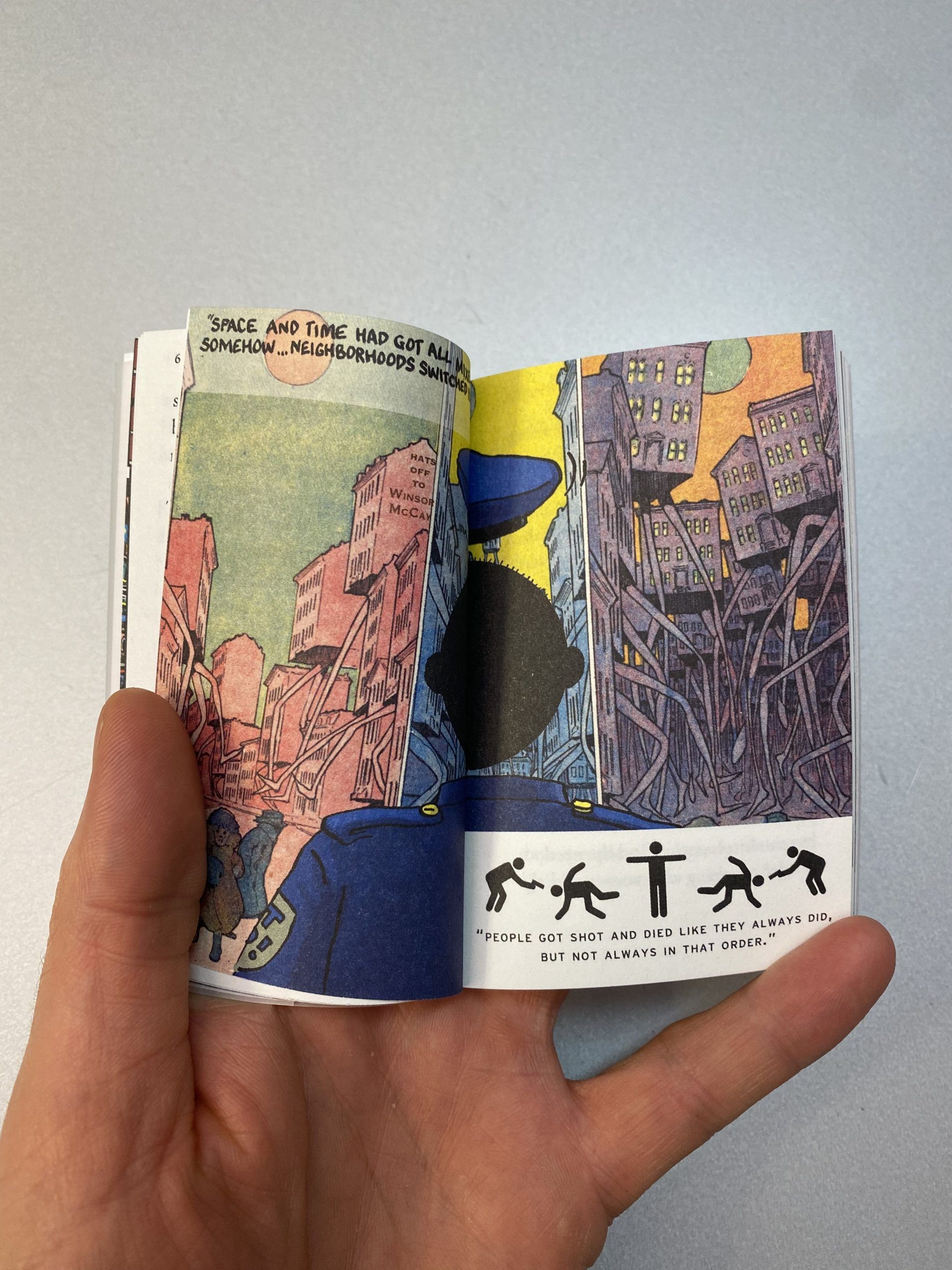

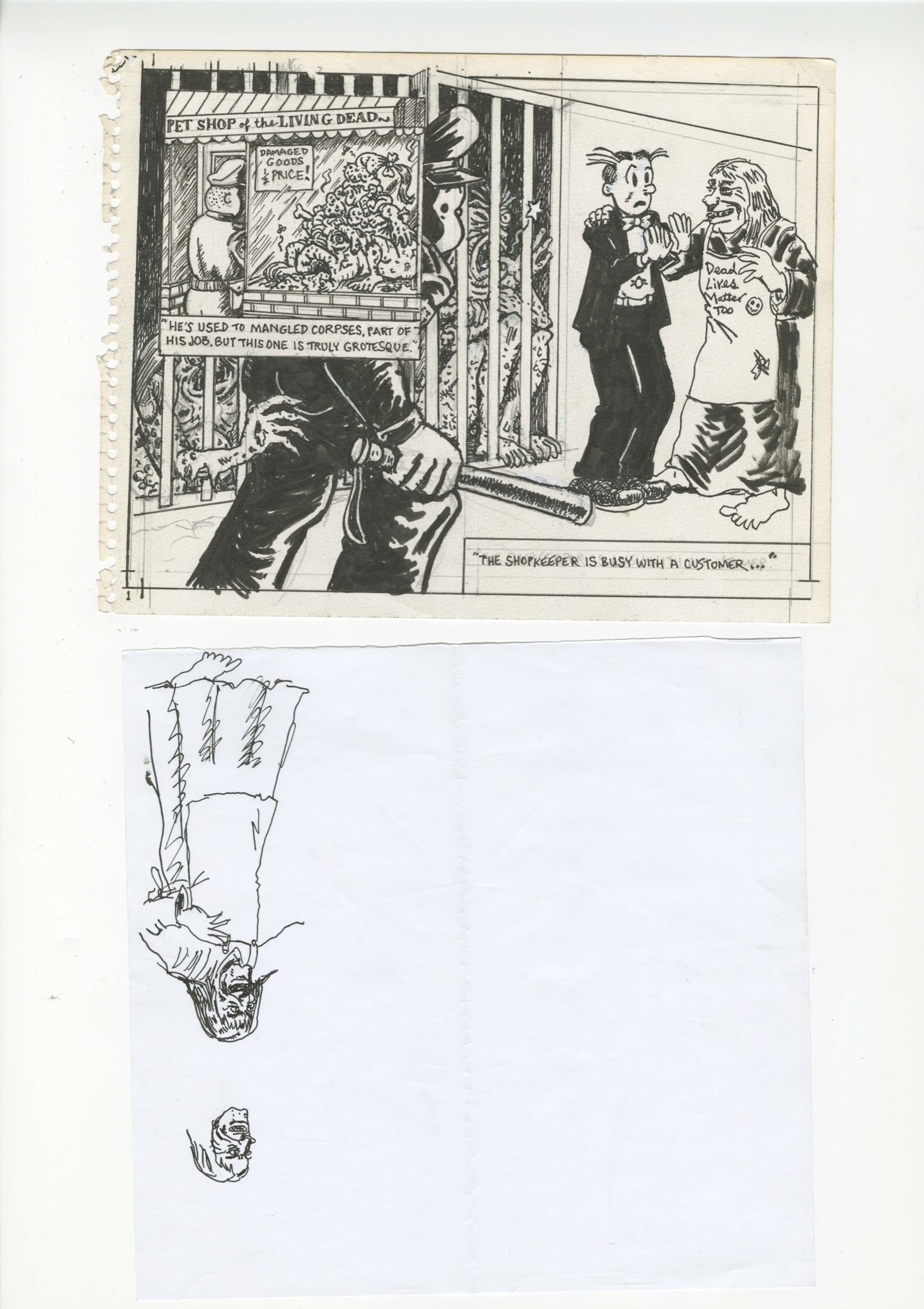

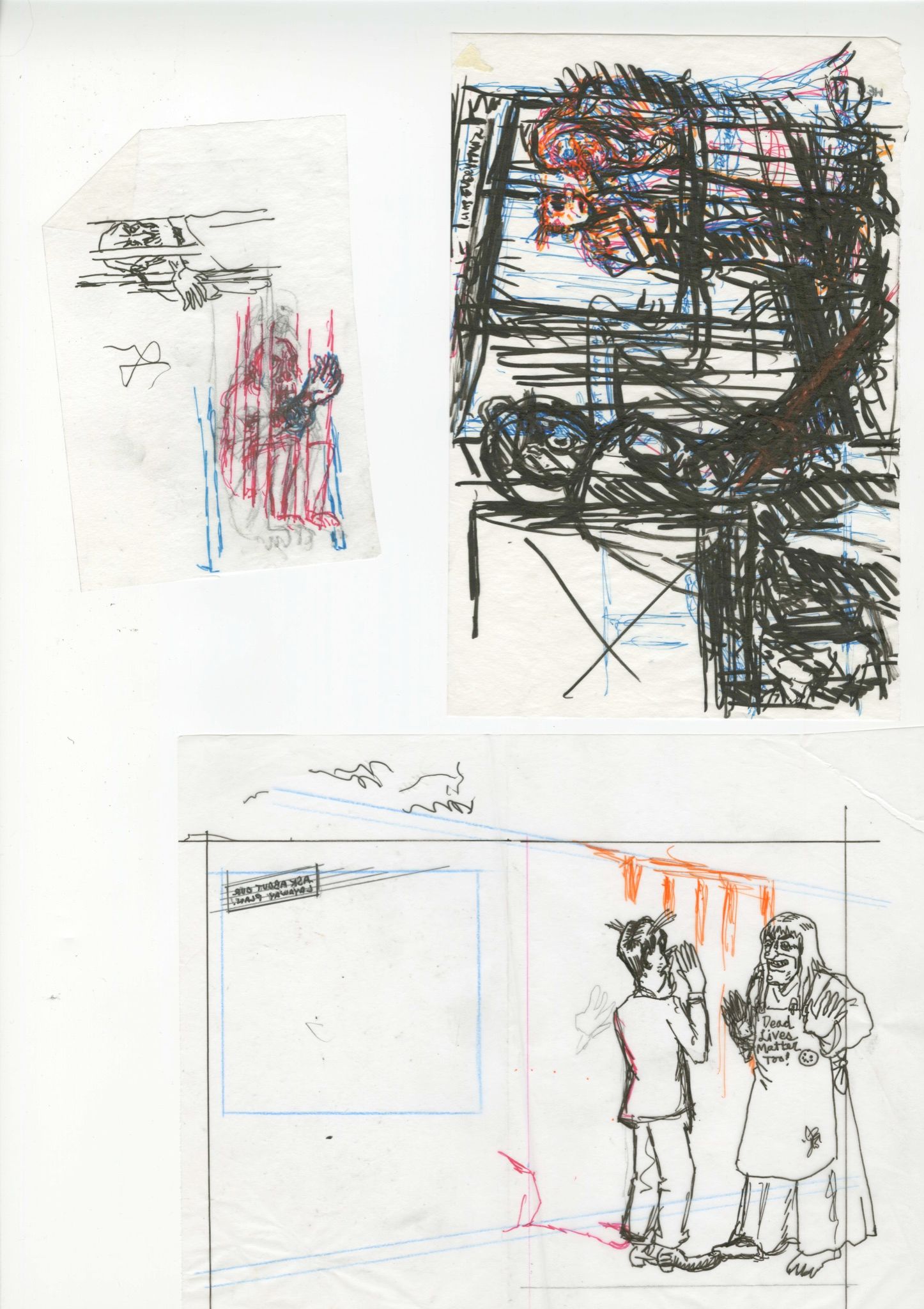

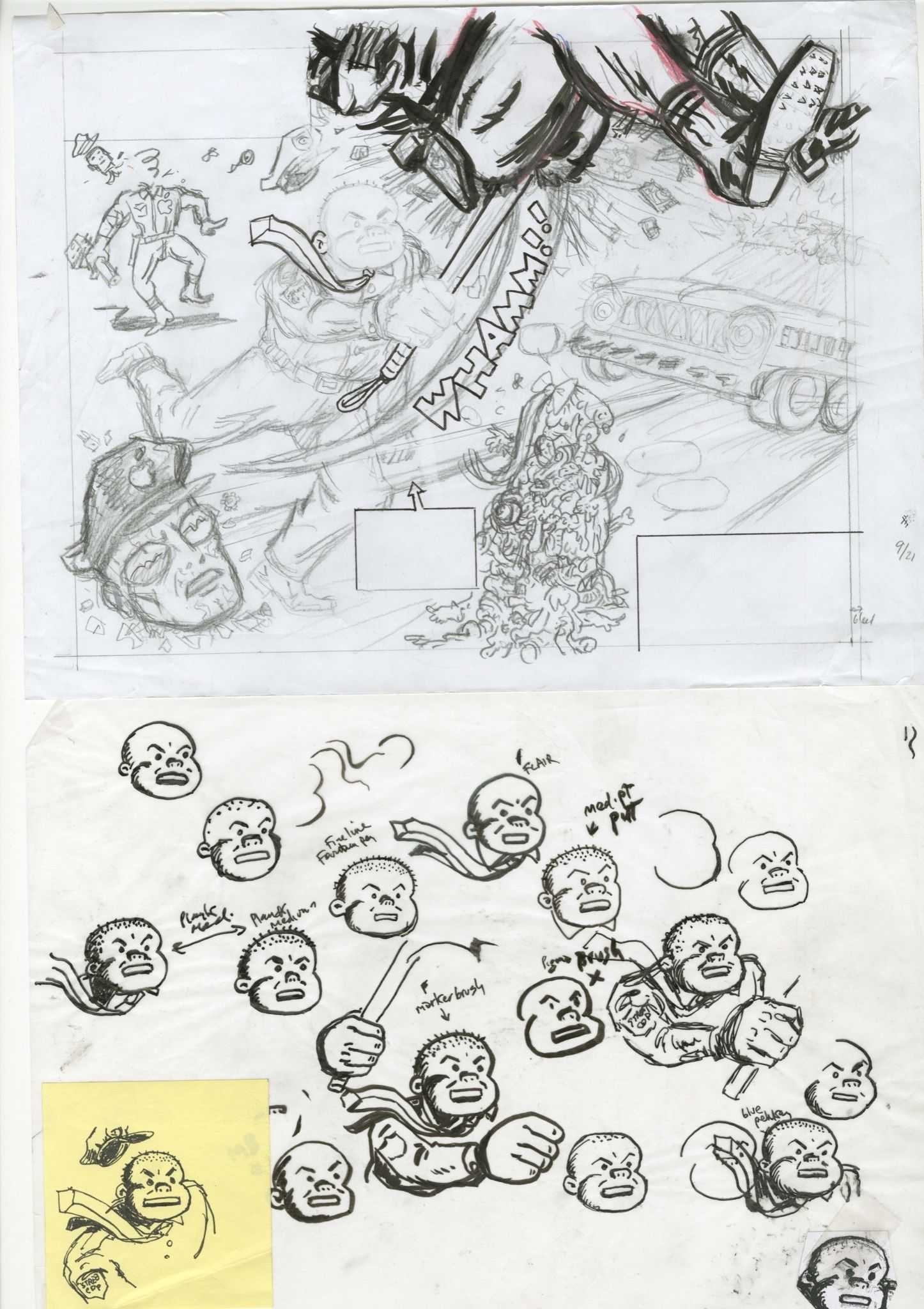

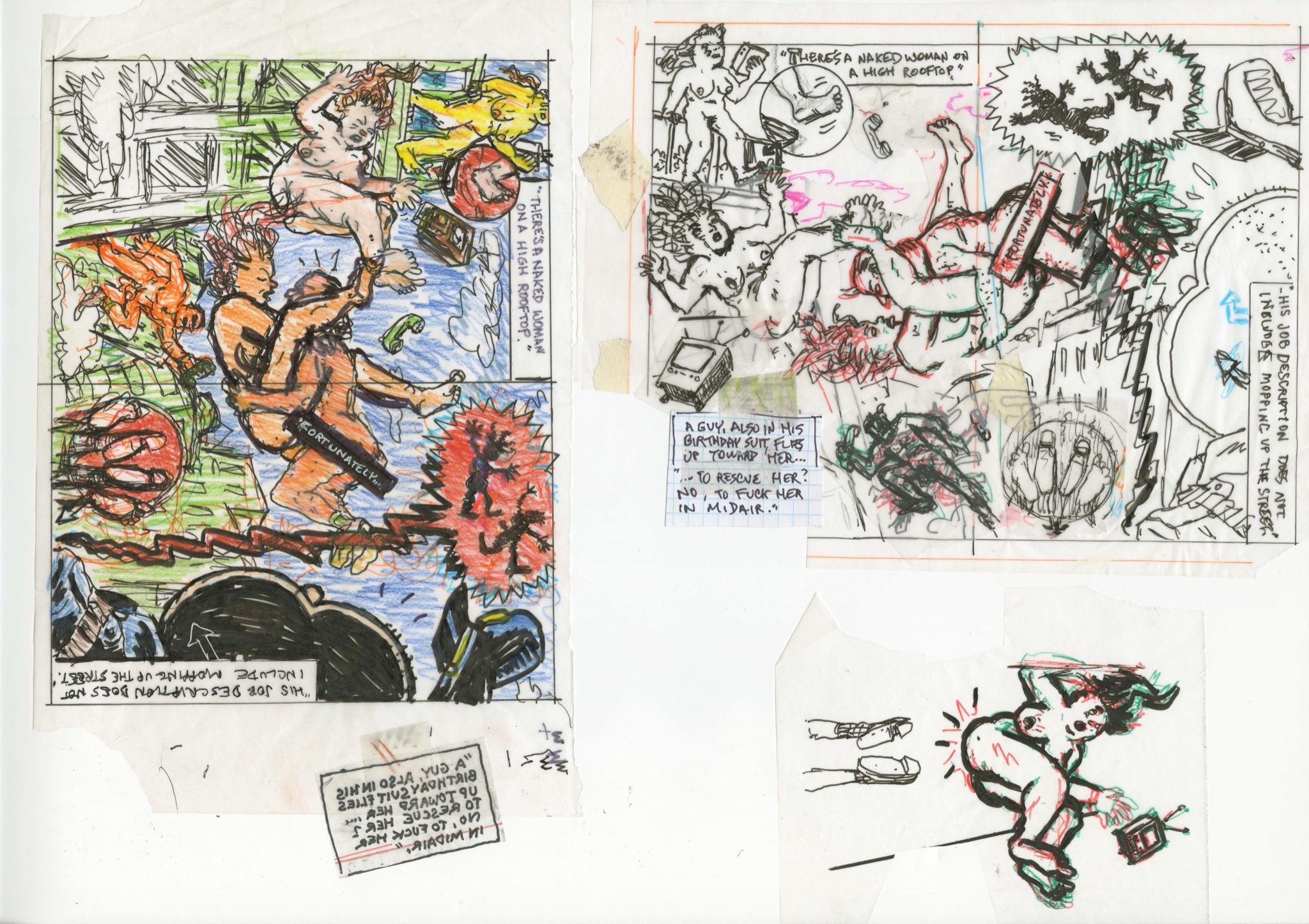

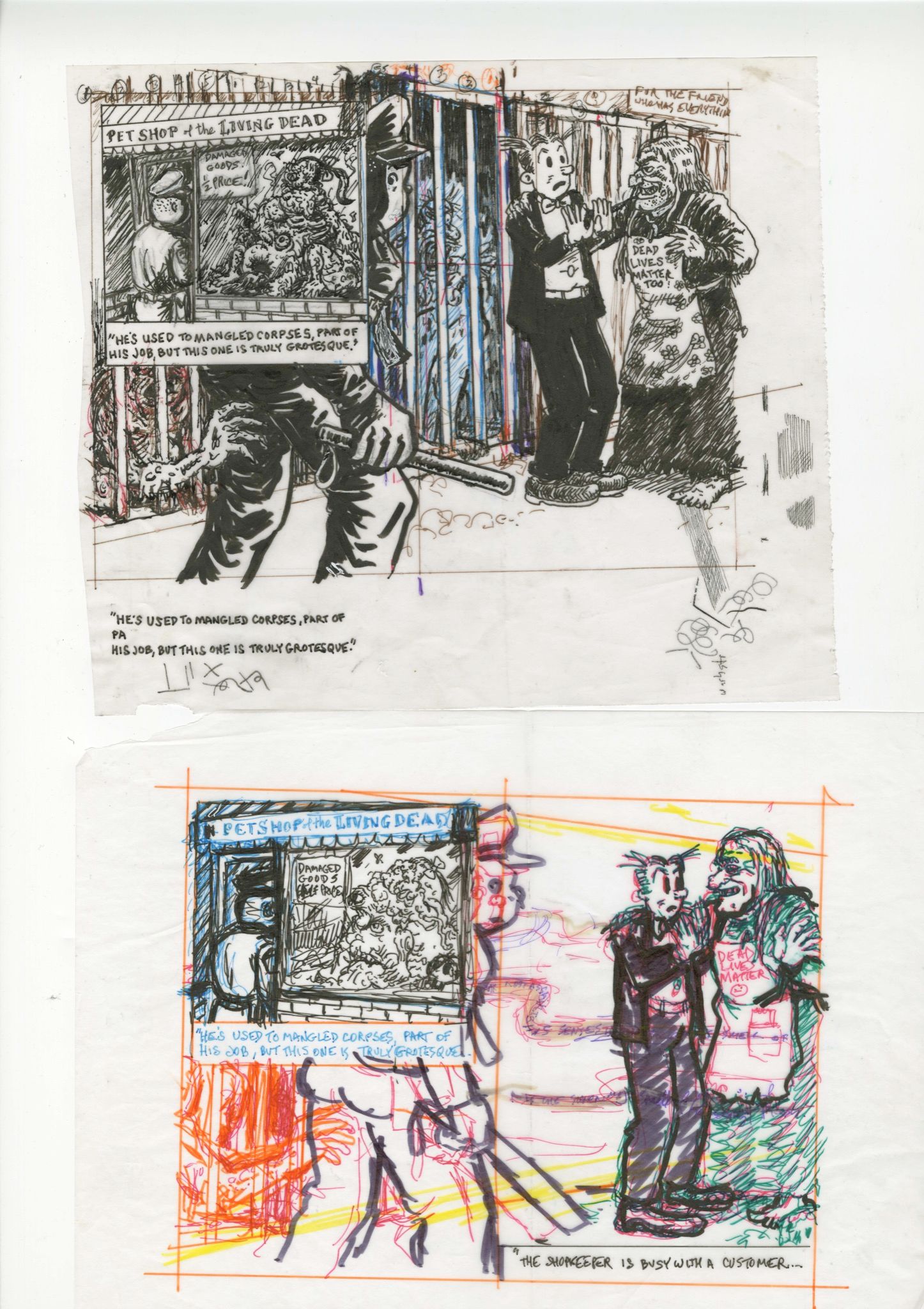

The Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist Art Spiegelman teamed up with Robert Coover for Street Cop, a detective novella that explores the American psyche, police violence, and the workings of memory in the digital world. Coover’s text – which is set in a dystopian world of living dead, murderous robotic cops, and streets that change locations – is accompanied by Spiegelman’s provocative drawings that are raunchy and wild and difficult to unsee once you’ve seen them.

Best known for his graphic novel Maus, Spiegelman, who also created the Garbage Pail Kids, spoke to 032c’s contributing editor Hans Ulrich Obrist about his collaboration with Coover for ISOLARII. In this far-reaching conversation recorded during the summer of 2021, Spiegelman discusses “schlubby” street cops, his “be a nose” creative process, the fluidity of time (in comics), and the importance of interviews.

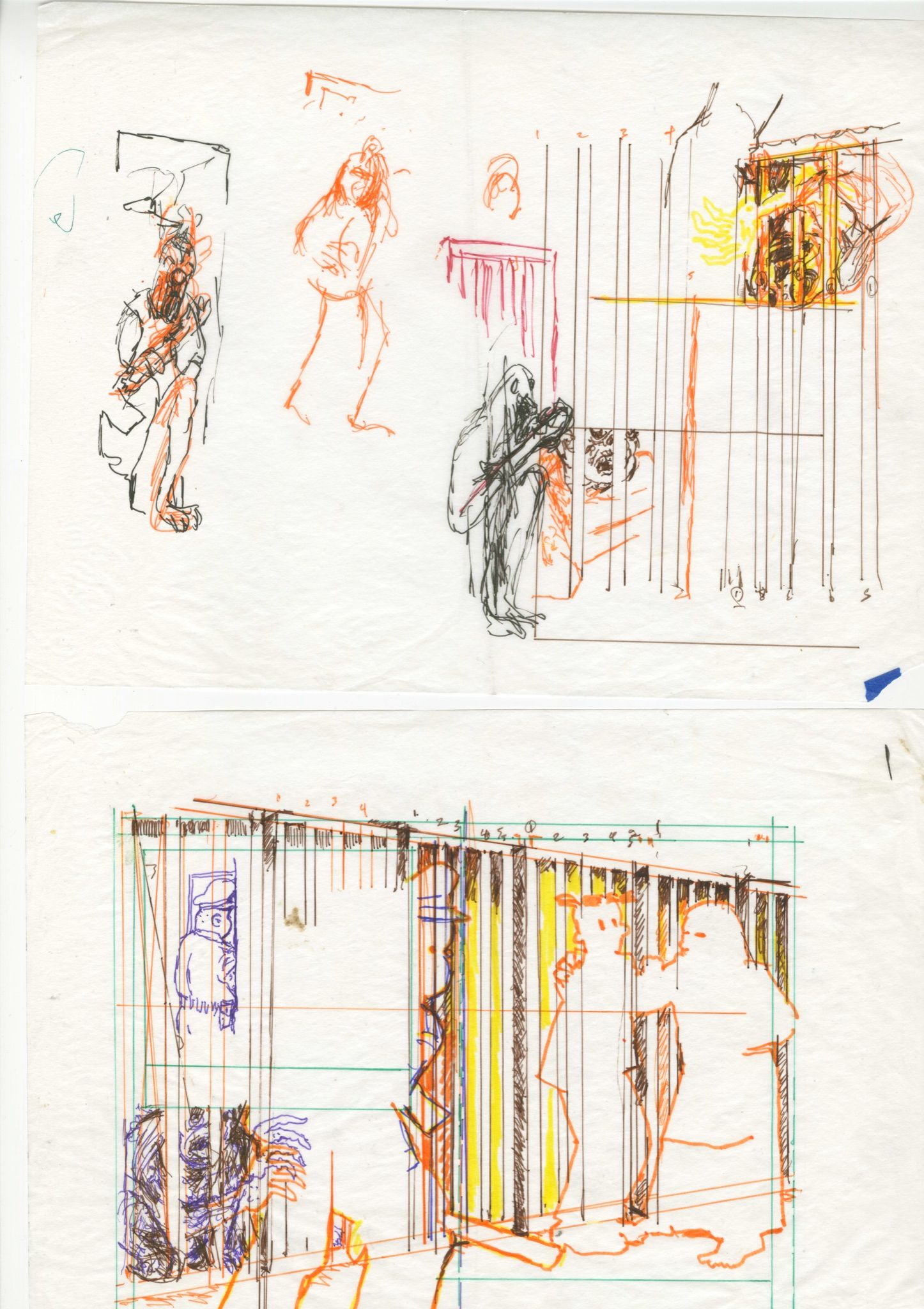

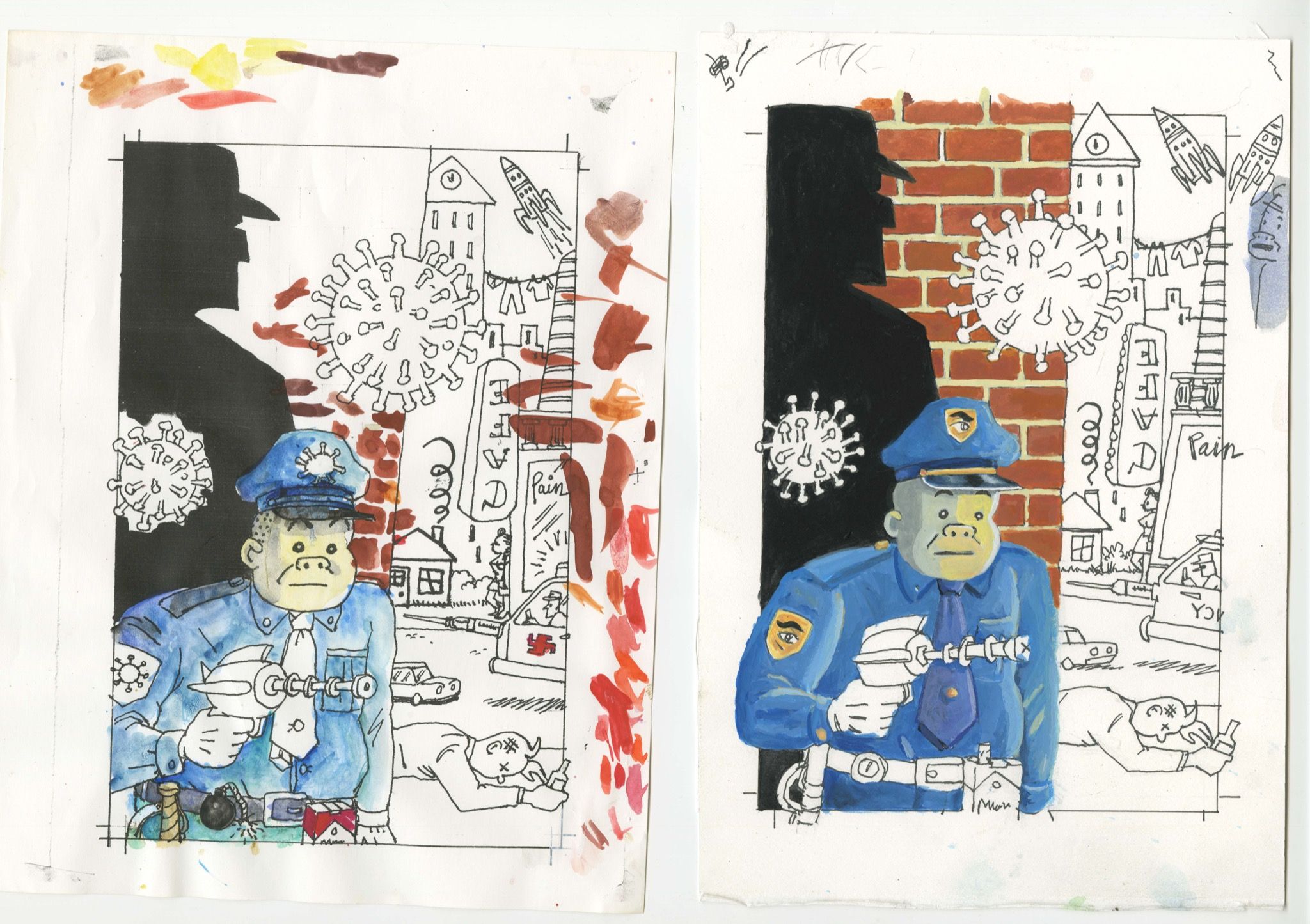

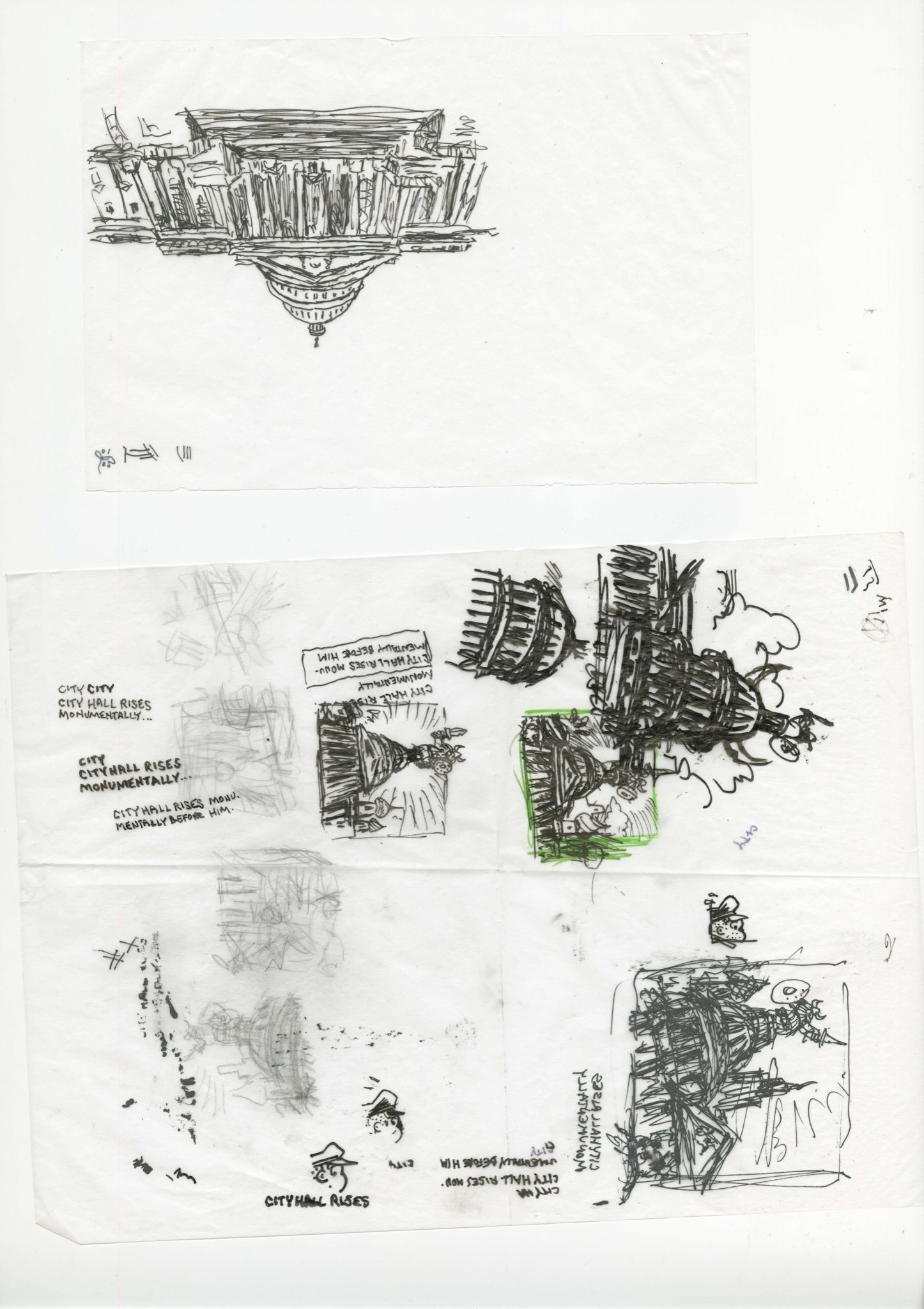

All images featured here are Spiegelman’s work-in-progress sketches for Street Cop, which were recently exhibited at Galerie Martel in Paris, courtesy of Art Spiegelman.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST: Where are you?

ART SPIEGELMAN: I’m in a cabin in northwest Connecticut, our bunker off and on for the last year or so.

You’ve been working in the countryside?

Yeah. I’ve been moving around a bit, but a lot of the time I’m up here.

Have you been working a lot during the lockdown?

Well, I did a whole project, Street Cop, and a pilot for Amazon Prime. And between times, I’ve just been lazy — when not fretting or worried about the world.

How did Street Cop begin?

My wife and I came to this log cabin the day after a lockdown was declared in New York, not knowing how long we would stay. I only brought this script I was working on and a sketchbook with me. My hand had gotten very rusty. I hadn’t been drawing much in the months leading up to lockdown. A sketch book is fine, but it often doesn’t have a real propulsive logic. So, I was very vulnerable when [Robert] Coover wanted to know whether I would illustrate a new book of his.

When I saw that the format was so small, I thought, that’s ideal because it’s something I can plunge into. It’s the size of a teacup. It’s not like plunging into an ocean. And yet, I can turn teacups into oceans with a flick of my brain! It ended up being an incredibly immersive project with Coover, a writer I’ve admired since his collection of stories Pricksongs and Descants came out.

I had never met Coover, but we talked on the phone for an hour. I was really happy to find a dystopia next door. It seemed like a good place to escape.

Did he tell you about the book?

Not so much. But he did say a few things that were very useful. One was, “Well, it’s about a dystopia. So that means, of course, it’s about the present.” The other useful advice was “just draw whatever you want.” It was a nice, open-ended invitation that made me do just the opposite, of course. I tried to stay very close to the story because I’m not really used to being an illustrator. At least insofar as I’m illustrating somebody else’s ideas rather than my own.

I found a way into the work when I realized that Coover, who is in his late 80s, and me, past 70 at this point, are both very comfortable in what he calls the old part of town. For this poor street cop schlub, it’s not because the old part of town is any better than the ugly, dystopian world he was living in. But he felt like the old part of town was more forgiving, more like him. I found that my old part of town is always related to comics, and so I started casting around for characters in this story that is very conducive to the language of comics. At first I searched for the street cop and tried things that looked like Humphrey Bogart, Broderick Crawford, or Dick Tracy, and eventually found a comics character named Sluggo.

Sluggo was a homeless kid, a pint-size friend of the titular heroine of the comic strip Nancy. If he were ever to grow up I thought he’d be kind of hapless and schlubby, like the street cop. I tried that as a drawing and liked it, and made a sketch of what became the frontispiece. When I sent it to Coover, he said, “By God, that is the street cop, you’re a genius!”

It’s ironic because I was trying to get away from the present, find a way to not think about the virus or street cops — which became front page news about a month after I had already started working on the book. But it inevitably inflected what the whole story was, and Coover’s vision, was large enough to encompass those things.

I was able to make myself at home in the dystopia next door, and find ways to make tiny pictures for this palm-sized book that didn’t feel like it was a shrunk-down miniature. It felt like its own size, and it should feel full, maybe even over-full, but not impossibly full.

“I think of illustration as a very pleasant decoration that helps make you interested in the book as an object, but that is somehow a kind of pillaging of the art of the writer.”

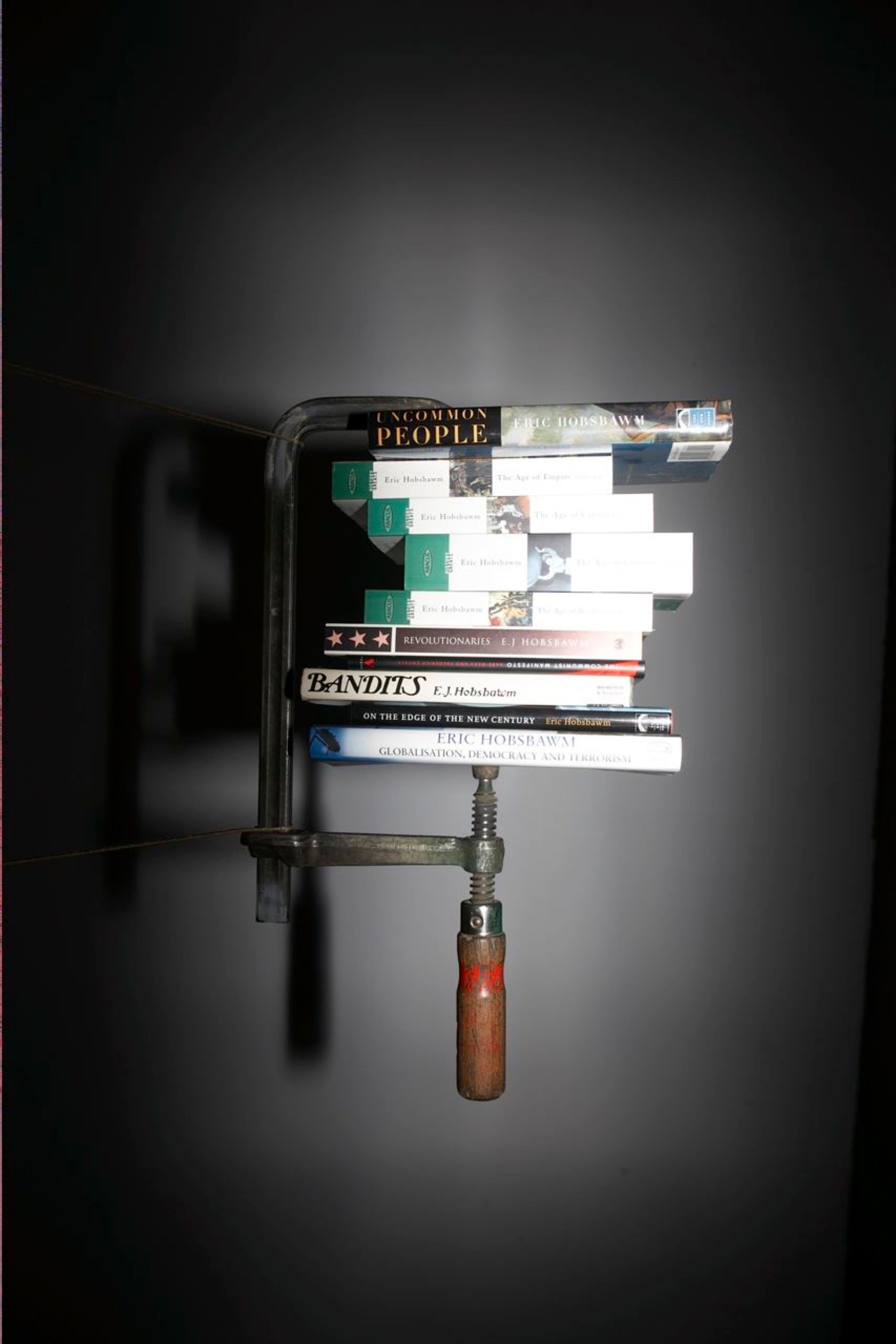

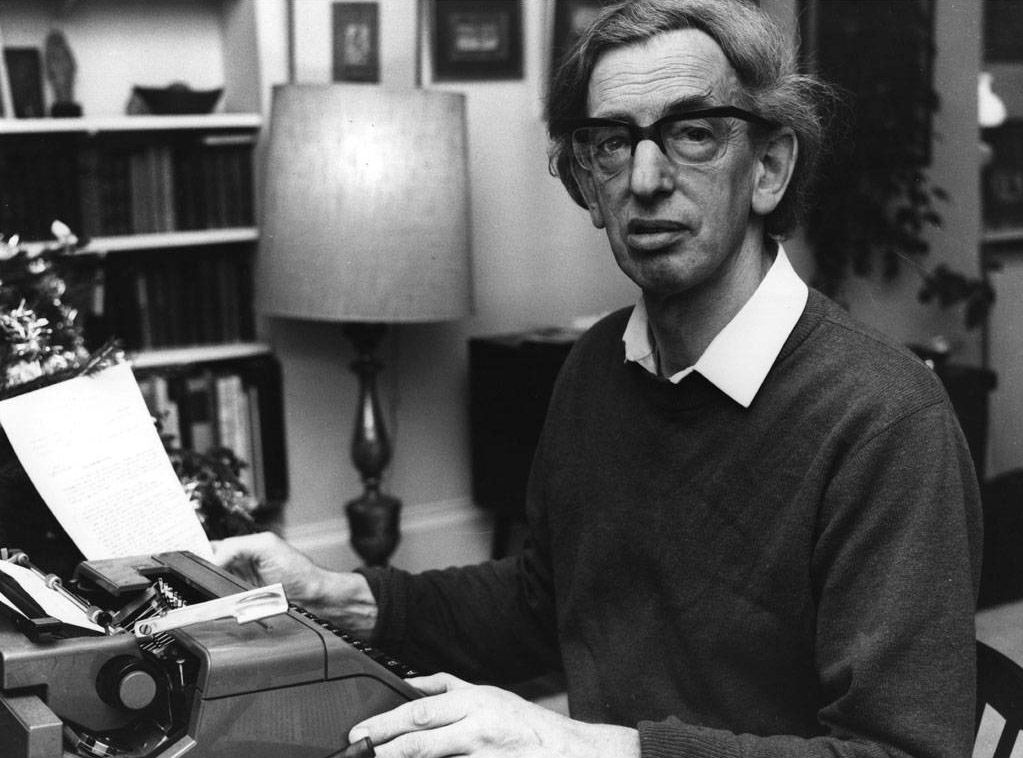

The book is also concerned with memory in the digital world. The late historian Eric Hobsbawm told me that even though we have more and more information in the digital age, it doesn’t necessarily mean we have more memory. He believed that amnesia might be somewhere at the core of the digital age.

I think we’ve outsourced our memory to the virtual world. I remember less and less, even before the brain fog of the last year and a half. Although I never had Covid-19, I had the brain fog that came with the Covid-19 era — my memory gets more and more faulty. But Google was invented as a kind of prosthesis for memory. One can just look up what one can’t remember, and pretty much get there within two or three moves.

I was interested in the aspect that relates to memory, which is tied to time in Street Cop, because it’s very fluid. You’re living in some kind of present/future with somebody who’s trying to go back to the past, by hanging out in dive bars and things like that, and finds a refuge in that other time.

Comics do this very naturally. When you look at a comic, you’ve got panel one, panel two, and panel three. The first panel is the present, because that’s what you’re looking at. The next one is the future. Which means that when you look at panel two, it’s the present and the panel to the left becomes the past. And from the corner of your eye, you’re seeing panel three, which is the further future. And of course, you’re seeing them all at once and shifting back and forth before you focus from looking to reading.

My favorite sentence in Street Cop is: “People got shot and died like they always did, but not always in that order.” I wanted to make pictures that would echo the fluidity of time in the text. I found that by having a picture on a double page spread, it could refer back to something that happened a page or two before, hence in the past, but then as you look at the picture from left to right, it moves into things that you haven’t read about yet, and you’ll see them a page or two or three in the future. So you’re kind of caught in this little wedge to move you through a different dimension.

It’s very unusual for you to work with an existing text, isn’t it?

It is. That’s why I said I’m not really an illustrator. I think of illustration as a very pleasant decoration that helps make you interested in the book as an object, but that is somehow a kind of pillaging of the art of the writer. You’re stealing something from the writer in order to give him a nice-looking book, but you’re stealing his vision of what the monster Electra looks like, of what the cop looks like, of where they are, and making it much more specific and replacing what would otherwise be whatever you have to construct in your own mind.

This has made me shy away from illustration of anybody else’s work. This book is only the second time I’ve entered into a book-length illustrating project. The first time was a book right after I finished Maus. Back then, I wanted something to draw that would be decorative, a little bit transgressive, maybe a little sexy, and more visually pleasurable than Maus, which had a very specific function with its pictures. So, I did a book in scratchboard illustration that mimicked the woodcuts I liked from the earlier part of the 20th century. It was for a book-length poem in rhyming couplets, The Wild Party, that was banned in Boston when it came out, about a party that leads to a murder.

The one time I met William Burroughs, I didn’t know what to talk about after we talked about cats, because I knew nothing about guns, so we talked about books a little bit. I asked if he had ever heard of the The Wild Party because I was staring at it on my shelf behind him and he answered “By Joseph Moncure March? It’s the book that made me want to be a writer.”

Then he recited, “Queenie was a blonde and her age stood still/ And she danced twice a day in vaudeville.” And proceeded with about 40 pages of this poem by heart that he hadn’t seen in decades. That helped me decide that this was a poem worthy of illustrating, even though most people would look at it and see an extended limerick — doggerel rather than poetry. When my version of the book came out, it had a quote by William Burroughs on the back and way more illustrations than I bargained for — I made upwards of 60 pictures.

Coover is famous for short stories — “The Babysitter,” for example — which are basically meta-fictional short stories. And I thought since we’re doing an interview, it would be interesting to move from meta-fiction to meta-interview. Could you tell me about the role of interviews in your practice? Even though you mostly do the drawings and write the text, you do use interviews in your work; the interviews with your father, your wife, your children were very important for the second volume of Maus.

Well, Maus grew rather organically, and had no choice but to be an interview. Or, let’s say, a deposition. Mainly, I was trying to solve a mystery for myself: how the fuck did I get born? Both my parents are supposed to be dead. And I didn’t know much about what happened to them. I just knew that they lived through this monstrous thing that was very hard for me to visualize.

It started with a conversation with my father that I taped back in 1972, I think. As I listened to the tape at the time, I realized this is what I have to work on. In 72, it led to a three-page strip. Then I went on to do a lot of other things, most of which were not interviews. But when I moved back from San Francisco — which was the capital of underground comics and where I was happily living as if it was Paris in the 1920s — I realized I have to let my father know I’m back in New York and see him, even though we got along rather poorly.

For a while I was doing a trick I learned from a Dick Tracy comic strip. I would call him and put a towel on the phone, because it makes it sound like you’re calling long distance. Or at least that’s what Dick Tracy Sunday pages said. So I pretended I was still living in San Francisco for a while. And eventually I realized the jig was up and I called him and said I’m back in New York and I went out to visit him. Very quickly I realized that by working on Maus again, I had a way to be with him that was actually comfortable. If I had a microphone between us it could act like maybe a crucifix held up to a vampire — it would provide protection and distance. So that’s interview one.

I revisited Maus in MetaMaus, which was built around several years of conversations with the comics scholar Hillary Chute. I followed this with shorter things that were — you’re right — based on memories of interactions with people or literal interviews. I did a comic strip based on my meetings with Maurice Sendak, and another one with Charles Schulz, who had written me a fan letter, which I thought was a joke or somebody pretending to be Schulz. It said: “If you’re ever out in Number One Snoopy Place in California, please come by and visit.” I went out and visited him after I found out that such a place existed. I also did a three-page comic for The New Yorker that was really built around a conversation or interview. So, you’re right, interviews appear more often than I would have thought.

Many years ago, I met Claude Lanzmann, who had spent 11 years conducting his own interviews for his documentary about the Holocaust. He divided the witnesses into three categories: survivors, bystanders, and perpetrators. Did you ever meet him?

I met him once and we talked about his three categories, which were then represented by cats, mice, and pigs in my book. I also told him how much I admired the fact that he didn’t use borrowed imagery and create an ersatz past and make it present, which is what most Holocaust movies do.

I found an interview where you said Primo Levi was a main inspiration.

Primo Levi really was important for me. In contemplating Maus, I really needed to find things that didn’t veer toward “holokitsch,” as I called it, or that tried to find meaning in what had happened. Primo Levi’s last book, The Drowned and the Saved, which is his most brilliant I think, is whatever’s on the other side of despair but still a neighbor of despair. Talking about the things that happened, and also the ways it still reverberates.

Another book that was really important for me was This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen by Tadeusz Borowski. He was a non-Jewish Auschwitz prisoner who was a leftist. The stories have a kind of quality that’s only available, perhaps, to somebody who wasn’t as immediately threatened with death. He has a hardboiled voice, almost as if Raymond Chandler had been in Auschwitz. All that hardboiled fiction has a kind of sentimentality to it as well as a gruff exterior. That was also important for me — not veering towards sentimentality, but still allowing for emotion to be present in an overwhelming narrative.

“I am followed by ghosts, first by the ghosts of my parents and ancestors and then by the ghosts of things I tried and abandoned.”

Drawing, you said, is always a struggle. Is writing always a struggle too?

Yeah, they’re both struggles, but drawing is way more difficult. When I did these 12 or 14 drawings for Street Cop, there were at least 20 sketches for most of them. I was trying to locate what I saw in my head and wanted to make. I’d have to make little sub-images to find the corners of the picture, how they worked.

Do you have any unrealized projects? We know a great deal about architects’ unrealized projects, because they have the habit of publishing them. But we know very little about artists’ or writers’ or poets’ or scientists’ unrealized projects. Of course, the range of unrealized projects is pretty wide, there are a lot of reasons why a project isn’t realized. It can be too big to be realized or too small to be realized or it can be too expensive to be realized or simply utopic or partially unrealizable. It can be also a dream, or it can be a forgotten project somewhere in a locker. But it can also be a project which was censored. And as my friend Doris Lessing always said, there are often projects which are self-censored, the projects one would have loved to do or would love to do but hasn’t dared to do.

Absolutely. I am followed by ghosts, first by the ghosts of my parents and ancestors and then by the ghosts of things I tried and abandoned. Many, over the years. Some of them just live in my sketchbook.

When I was starting Maus, I was actually working on another project that is now a phantom project — A Life in Ink. My wife Francoise had a printing press in our loft at the time and I had the idea of making a project about the life of a fictional cartoonist who is born at the dawn of comics at the end of the 19th century and lived up into the underground comics era. We were going to make this box that had all these books and booklets in it that would include collections of his comic strips when he was a successful comic artist, some of his lesser known projects, things that were licensed from him, his diary that had pictures and writing in it, and would compositely make up a life of comics and his life. I abandoned it after I decided to start on Maus.

After Maus, I had an idea for a book, but it was really only an idea. And maybe there’s a degree of self-censorship involved in walking away from it. I had a great title and a great concept, but I didn’t really want to spend the next 13 years on it. It was called A Land Without People. This is how our people used to refer to Israel — Jews used to refer to Israel as a land without people for a people without a land. And there’s a deep fallacy in this, since there were people on the land.

And after having done Maus, to populate this land without people for people without a land with different animals was going to be a way to dive into this Gordian knot of what the hell Israel is and why it is. The more I read, the more I was grateful that my father and mother came to America rather than to Israel, and that I could then continue to be part of the rootless cosmopolitan world of the diaspora rather than having to dive into misguided nationalism.

That project is unrealized. That was just notes and a lot of reading and a lot of little attempts at making something. And then there are millions of things that I’ll one day wake up and go, yeah, that’ll be great, and the next day it just remains a couple of pages in my sketchbook. Those would be the main landmarks.

You’ve referred several times to your notebooks — can you tell me about your notebooks, and have they ever been published?

There’s one moment, I don’t remember when anymore, where I decided to make something every day no matter what. For a short period of time I could pretend to be a cartoonist who had a daily practice. McSweeney’s published it as part of a multi-volume issue and then they asked whether they could have more notebooks. I realized I could give them an anthology from different notebooks as well as one other intensive notebook I had done years earlier. So, I did that plus a very short, fragmented notebook, and a booklet explaining why I don’t keep sketchbooks regularly. And they made that into a bundle called Be a Nose.

The title came from the way I approached drawing, which reminds me of an obscure movie called A Bucket of Blood from 1959. This movie’s about a hapless protagonist who is working as a schlub in a coffee bar. The other people at the coffee bar are all artists, poets, writers, and he’s very envious, because they get all the girls. So he decides to become an artist. At the start of the movie, he’s trying to become a sculptor, and he’s living in a rooming house. And he’s bought this giant wad of sculpting material. And as he’s chiseling at this thing that he wants to turn into a bust, he’s going, “Be a nose, be a nose, be a nose!” And it’s not looking like anything, but he’s chipping off little bits of the marble or whatever. And then he throws it into a wall in frustration. It goes through the wall, hits a cat, and kills it. The cat then falls into a bowl, and gets covered with plaster that was cooking in this bowl.

The next day the protagonist goes out and successfully picks up a woman who’s intrigued by the fact that he’s a sculptor. She comes back with him to see what he’s sculpted but isn’t interested in most of what she sees. But when she sees this plaster-covered cat — hardened plaster with a blade sticking out of it that had been thrown, and the chisel — she says, “That’s great, what do you call it?” “Dead Cat.” And she says, “Wow, heavy.” And that becomes his art.

He kills her and that becomes the first of his other sculptures in this horror movie. But that moment where he’s sculpting has stayed with me forever. It’s the way I approach drawings, like, “be a nose, be a nose, be a figure with the arm twisted at this angle and the head seen from over here that looks distorted but not ungainly.” It takes just blind stab after blind stab of chiseling until it finally turns into what I want.

Rainer Maria Rilke wrote this lovely little book which is advice to a young poet. And I was wondering what would be your advice to a young graphic novelist, cartoonist, or writer in 2021.

I’m afraid my advice wouldn’t be a whole book, it would be more like a haiku. Something like, “Follow your own compulsions and your needs.”

What I liked about comics and still like about comics is that when it’s done for its own sake you have no choice but to do it. You need to use both words and pictures, narrative and visual ideas that can’t be reduced to words, together. You find your way; and after a while, some surprising things can happen and do happen. So, I can’t really give you advice beyond, “If you’ve got to do it, please do it.” It’s a little bit like that great line by Wallace Stevens who was told, “There’s no money in poetry,” and responded with “Yes, but there’s no poetry in money either.”

Credits

- Interview: Hans Ulrich Obrist