ABC of CdG

Born in Tokyo in 1942, Rei Kawakubo started the clothing label Comme des Garçons in 1969. The shockwaves sent in every direction by her Paris debut, in 1981, continue to reverberate with power: every important designer of our time admits to her influence, and not so long ago, the critic Suzy Menkes declared her “one of the great fashion forces from the last decades of the 20th century to now.” Through it all, Kawakubo silently reigns over a business that is as meticulously crafted and complex as any garment to emerge from her famous patterning studios. In 032c’s Issue 20, we devoted a 40-page section to Rei Kawakubo at COMME DES GARÇONS. Here, our specially compiled alphabet, frozen in 2010, systematically uncovers the enormous diversity of response that Kawakubo’s work has provoked. Next, in a candid personal essay, American filmmaker John Waters shares his life with the label and its designer. Hilton Als, of The New Yorker, closes the dossier with a note on love, loss, and Comme.

A

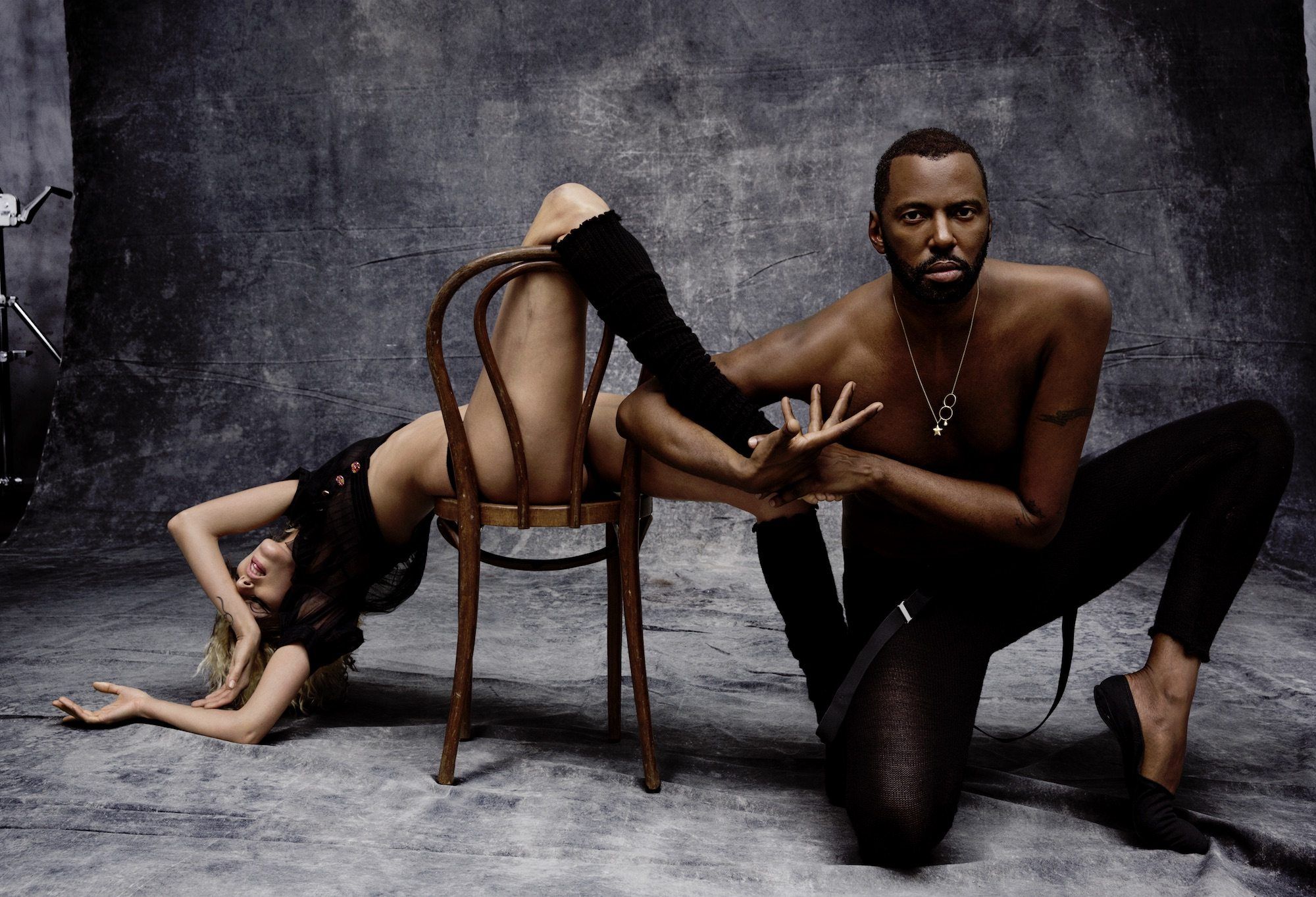

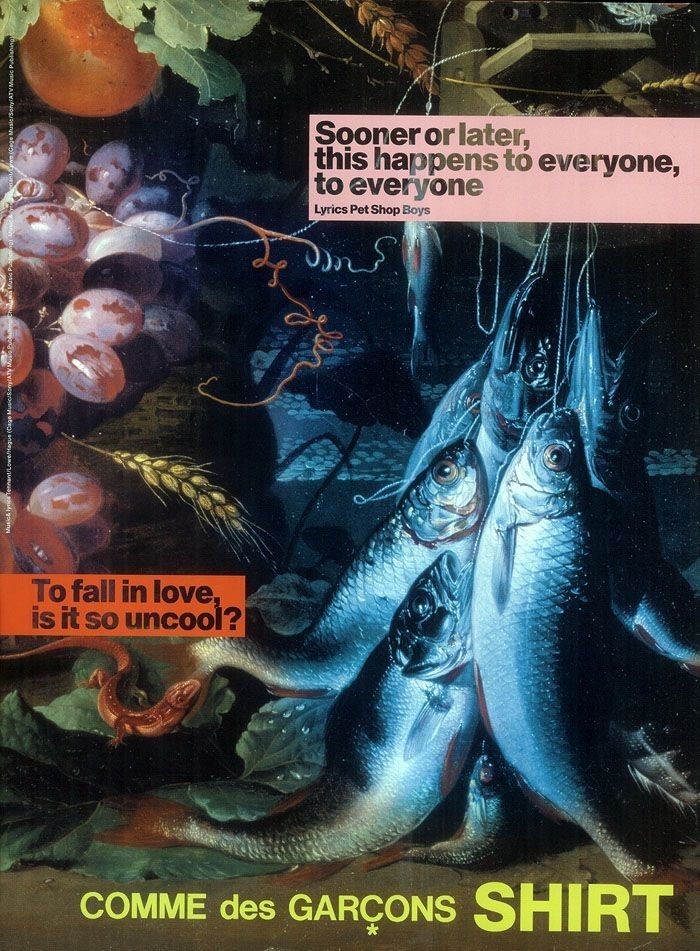

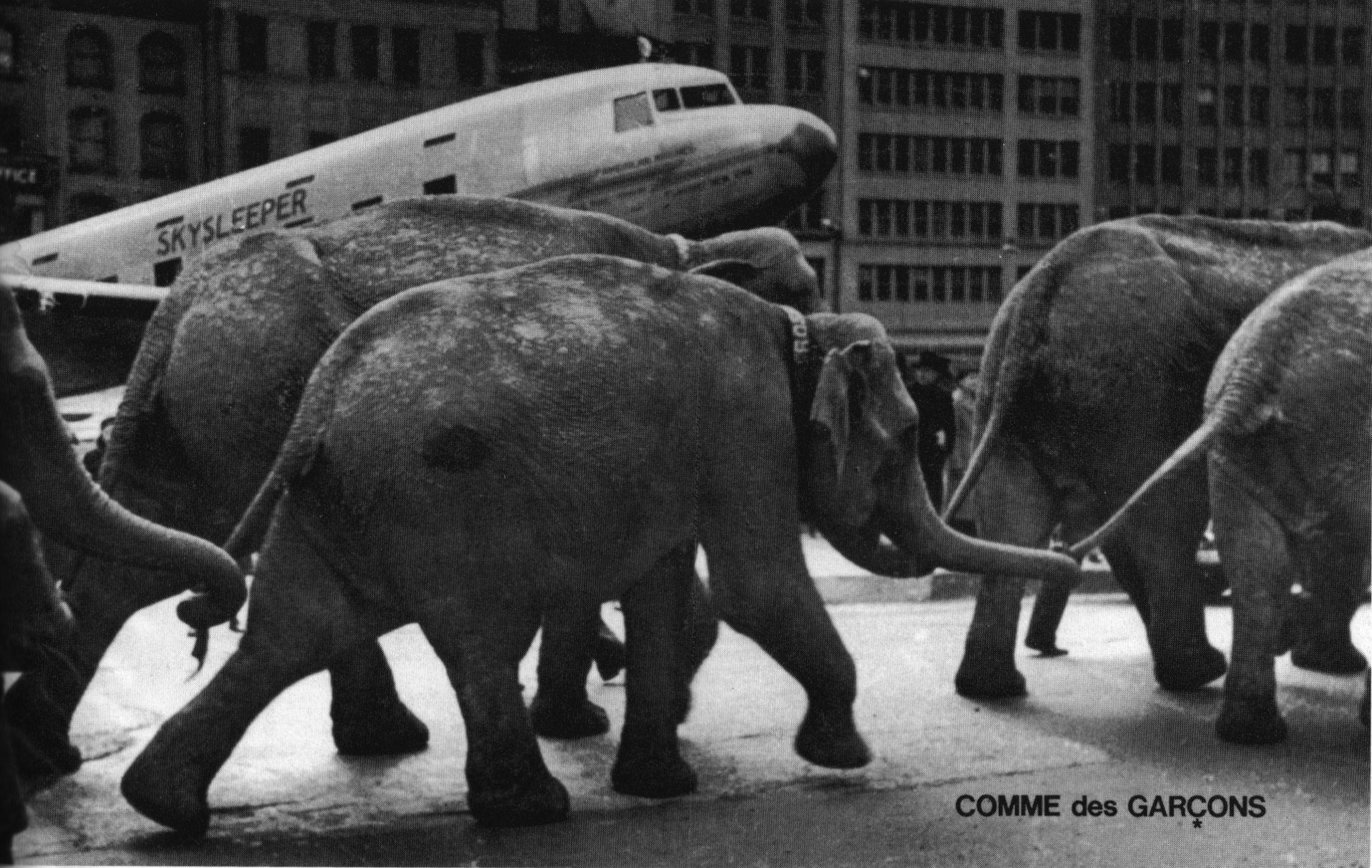

ADVERTISING

Alice Rawsthorn: “Comme des Garçons’s Shirt campaigns are a beacon of inspired eccentricity. Since they began 11 years ago, the ads have featured everything from icebergs, graffiti, blues lyrics, 16th-century Flemish paintings, trucks, dogs, birds, vintage pins, cave paintings, trucks, dogs, street photography, Pet Shop Boys’ lyrics, underground comics, punk poetry, shredded 1970s porn, the winners of a literary booby prize for the worst opening sentences of novels, a recycled trade advertising campaign, bizarre amateur inventions and the self-portraits of an unknown Danish amateur artist to – once but only once – a bunch of people actually wearing shirts.”

Ronnie Cooke Newhouse: “I’ve always been a big, big fan of Rei’s. I was one of four people who started Details magazine in the 1980s. Rei was a sort of demigod to us, and we were one of the first magazines to cover her, if not the first in America. When I later became creative director of Barney’s (the New York department store) I got to know Rei and Adrian Joffe. We stayed in touch when I left Barney’s, and when I opened my (design) studio in London they spoke to me about working with them.’

Alice Rawsthorn: “Perhaps because the Shirt campaigns are conceived by a creative director who edits the contents from ready-made imagery rather than by the fashion designer and photographer who produce them, the only consistent thing about them is their inconsistency. Yet collectively they build a compelling portrait of the brand as well as of its creators and the people who will wear the clothes.”

Alice Rawsthorn, “CDG Advertisements,” Paradis #5, Fall/Winter 2009.

ANIMAL

“I love all animals.”

Rei Kawakubo in Ronnie Cooke Newhouse, “Rei Kawakubo,” Interview Magazine, November 2008.

ANTI-FASHION

“In addition to consistently creating collections of clothes that challenge other designers to think outside conventional modes of production and beauty, Rei Kawakubo has also built a considerable international business. In this sense, her contribution could never be regarded as outside or ‘anti’ the fashion industry, though at times its aesthetic may appear to be delightfully at odds with prevailing trends.”

Penny Martin, The Power of Witches, Showstudio, 2004.

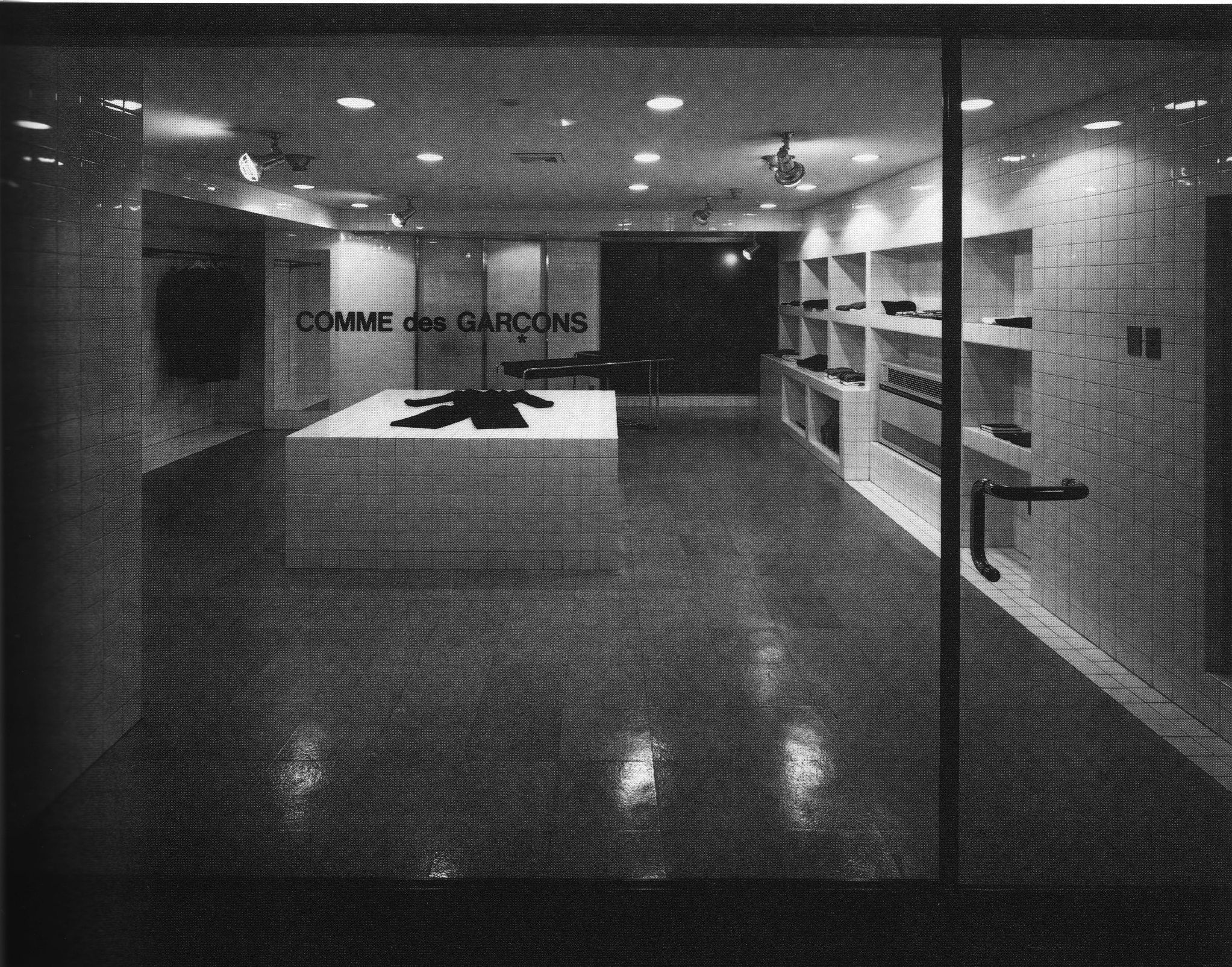

AOYAMA

The Tokyo neighborhood is the origin and continued nucleus of the Comme des Garçons universe, where the label’s first store opened in 1976, and home to this date of its offices, studios and mother flagship.

ARCHITECTURE

“Architecture has been largely unable to accept the excessive and formless nature of shopping.” So declared Rem Koolhaas, et al, in a well-known book from 2002. But since the late Seventies and Eighties, when she opened her first, then-radically minimalist boutiques – one was entirely empty, a stunt others are still repeating more than two decades later – Rei Kawakubo has been bringing both excess and formlessness to architecture. Consider her store design heyday of the 1990s and early Noughts – a golden era of blue-dotted glass and swooping hand-brushed aluminium (Tokyo Aoyama and New York Chelsea, respectively, both designed by Future Systems); of spinning stools in shocking red (Paris, by Ab Rogers and Shona Kitchen); of monolithic black (Kyoto, attributed to Kawakubo herself).

Working with other designers – or more frequently, with her longtime collaborator, the Japanese architect Takao

Kawasaki– Kawakubo has brought to retail architecture the same brilliantly warped, twisted sensibility that she’s given her fashion. That is to say, in her hands, the body becomes just as deformed as the space it inhabits with the result being, often enough, elusive. Her temporary Comme des Garçons guerilla stores can be given credit (or blame) for the recent pop-up shop mania. Her Dover Street Market, with all its tin shack and Porta-Potty accoutrements, blurs the distinction between department store, luxury flagship and flea market. With Kawakubo, you’re never quite sure where the thing itself begins and the idea of it ends; her shops are less like spaces than, well, concepts (but please don’t call them “concept shops”).

Which is why Kawakubo has in many ways been one of the most interesting architects around. To be sure, her stores have been chockfull of spatial

acrobatics; but they have just as easily disappeared. Koolhaas may have had his “epicenters” (as he called his Prada flagships), but Kawakubo was one of the first to realize that architecture, like shopping and fashion, is fleeting.

ARIC CHEN, design critic, for 032c.

ARRIVAL

“I never intended to start a revolution. I only came to Paris with the intention of showing what I thought was strong and beautiful. It just happened that my notion was different from everyone else’s.”

Rei Kawakubo in Judith Thurman, “The Misfit,” The New Yorker, July 4, 2005.

“It’s a choice, one that implies a different approach. French eroticism stands no chance in this game, as the sensitive points of our feminine mythology – waist, hips, thighs – are quite simply avoided.”

French journalist on seeing a Comme des Garçons collection in 1984, cited by Olivier Saillard, Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Paris) 2010.

AVANT-GARDE

Rei Kawakubo believes that being avant-garde has become a cliché.

B

BASQUIAT, JEAN-MICHEL

Jean-Michel Basquiat, model, on the Comme des Garçons runway; Paris, Spring-Summer 1987.

BERLIN

“Joffe and I spent a day in Berlin at a Comme des Garçons ‘guerilla store,’ which then occupied the former bookshop of the Brecht Museum, on a seedy block in the eastern sector of the city. It is part of an experiment in alternative retailing (inconspicuous consumption) which the company launched in 2004 … Each of the stores is an ephemeral installation that opens without fanfare and closes after a year. Their decorating budgets are less than the price of some handbags at Gucci and Prada and original fixtures, including raw cinder blocks and peeling wallpaper, are left as they are found. Brecht might have approved the poetic clothes and the proletarian mise en scène, if not the insurrectionary conceit. ‘But the word “guerilla” as Rei understands it isn’t political,’ Joffe says. ‘It refers to a small group of likeminded spirits at odds with the majority. She’s fascinated by the Amish, for example, and the Orthodox Jews.’”

Thurman, 2005.

BROKEN BRIDE

Universally admired collection, Autumn/Winter 2005.The audience received its presentation at the Ecole des Beaux Arts with a seven-minute ovation. Through it, Kawakubo remained backstage. “It wasn’t simply a collection about weddings, although that may have been the first word. By breaking the rules of wedding dresses, by going behind the idea, there was born the further information that marriage is not necessarily happy.”

Rei Kawakubo in Suzy Menkes, “Positive Energy: Comme at 40,” The New York Times, June 8, 2009.

BUSINESS

“Unlike many fashion designers who find themselves embedded in industrial or financial conglomerates, Kawakubo is president of her own company of 450 employees and retains overall responsibility for both creative and business decisions. Nothing she does is an indulgence; all her work is part of a carefully considered strategy in which economic success is an essential part of maintaining her creative independence.”

Sudjic, 1990.

“She’s in control of every facet of her multimillion-dollar brand Comme des Garçons… This mellifluous phrase characterizes a philosophy of freedom when it comes to clothing construction… as well as presentation style and marketing strategy.”

Dolores Slowinski, “Fashion is not Art,” Detroit Metro Times, February 2008.

As the fashion industry was being turned upside down by the Great Recession of 2008, desperately slashing prices and cutting costs, Rei Kawakubo chose a different strategy altogether. She launched Comme des Garçons Black, a brand new recession-friendly collection that reprised the best selling styles from the brand’s archive at honest price points. It was a characteristically business-savvy move by a designer who has deftly managed the fine line between creativity and commerciality. Loyal fans of the brand kept coming back to Comme des Garçons, even if times were tough and money was tight.

Not all of Kawakubo’s avant-garde peers have fared as well. Despite his immense creative talent, the recession brought Yohji Yamamoto’s business to its knees, just before it was saved at the last minute by a private equity investor. On the other end of the spectrum, fashion genius Martin Margiela quietly left his eponymous label when its owner, Staff International, began the crass commercialisation which served to alienate Margiela’s core cult customer base, even if it managed to grow the business’ top line revenues.

So what’s the secret to Comme des Garçons’ success?

Kawakubo has been discreetly building a multi-brand fashion business, all under the Comme des Garçons banner. From the runway collection to Comme des Garçons Black to Play Comme des Garçons, a healthy fragrance business including collaborations with Daphne Guinness and Stephen Jones, as well ongoing CdG labels for Junya Watanabe, Fumito Ganryu and Tao Kurihara, there is plenty of choice for all types of consumers. And all of it offers a special piece of that Comme des Garçons spirit, unadulterated. In short, Kawakubo has maintained her fashion integrity, while building an enviable global fashion business as well.

Kawakubo once told Suzy Menkes, “It is true to say that I ‘design’ the company, not just clothes. Creation does not end with just the clothes. New interesting business ideas, revolutionary retail strategies, unexpected collaborations, nurturing of in-house talent, all are examples of Comme des Garçons’ creation.” Perhaps this is the most important point of all. Rather than seeing business thinking as a blight on the face of her conceptual approach to fashion, she views it as central to her creative process.

IMRAN AMED, Founder and Editor in Chief, The Business of Fashion, for 032c

“If as Andy Warhol proposed, ‘Business art is the step after art,’ Comme des Garçons is its fashion manifestation. Kawakubo is a fascinating anomaly, since her artistic practice remains legible and assertive, even in the context of its uncompromised commercial intent. The disparate parts of her business – the architecture and fixtures of her shops, the typography of her graphic programs, the siting of her boutiques, the collaboration with artists, photographers, musicians, and architects, the selection of her employees, the unconventional models in her runway presentations and their hair and make-up, even her terse epigrammatic responses in interviews – comprise a unified project.”

Harold Koda, “Rei Kawakubo and the Art of Fashion,” Refusing Fashion exhibition catalogue, MOCAD 2008.

As Sonya Park, a stylist in Tokyo who knows Kawakubo well, said recently, “She makes her profit so that she can do something new the next season. It’s always about the next project.”

Cathy Horyn, “Gang of Four,” The New York Times, February 24, 2008.

C

CELEBRATION

“I went to the Comme des Garçons shop in Aoyama to see if there was a dress I could wear for the Pritzker ceremony. And I asked one of the store salesperson if there was anything good to wear for the ceremony. He kindly informed that to Kawakubo-san, and Kawakubo-san suggested to make something special for the special occasion. She first showed me some dresses from last collection and they were all so beautiful. She gave me some advice on which dress would look good on me. Kawakubo-san made some adjustments to fit to my body and made it very special. It was such an honor for me to wear that dress at the Pritzker ceremony. I received so many compliments from many people at the ceremony for the dress!” SEJIMA KAZUYO, principal, SANAA, to 032c. Interview by Vicente Gutierrez.

CHAMPIONS

Ten world records were broken by the U.S. men’s swimming team during the 2008 Beijing Olympics. All were achieved in suits from the Speedo LZR Racer line

with graphics by Comme des Garçons. “The suit was developed in association with the Australian Institute of Sport. NASA’s wind tunnel testing facilities, and Ansys fluid flow analysis software supported the design.” www.wikipedia.org

COLLABORATION

“Not that she ever approaches such a project as a brainstorming or a meeting of the minds. It’s more the case of a willful designer making a strong proposition with a partner who brings something new to the table, like production knowhow or distribution muscle.”

Miles Socha, “Comme and Go,” W, September 2008.

In the playful rulebook of the house of Comme des Garçons, collaboration has always been a cortex for the company’s inner sapience and variously articulated modi operandi. Rarely logical, these mutual efforts go beyond even their own expected aesthetic promises, issuing forth precise branding statements, and opening new outlets for the label’s continuous expansion – not to mention the added value they also give to guest

crusaders.

For more than 40 years, the company has elaborated a myriad of surprising and unexpected collaborative threads that few art or fashion historians could sufficiently document. Unleashed from an understanding of market-trend value, but also somehow solely guided by Rei Kawakubo’s progressionist love of all things cultural, artistic, and emotional, Comme’s collaborations are rarely executed at the behest of others (you never request, you are always invited – somehow mirroring the pyramidal structure of the company itself). Still and all, the list is endless …

There’s photography (Cindy Sherman, Daido Moriyama, Collier Schorr …); sculpture and installation (Fischli/Weiss, Roman Signer, Felix Gonzales-Torres…); advertisement (pretty much all of the previously mentioned above and below!); set design (Gary Card, Jan de Cock…); dance (Merce Cunningham with Scenario [1997]); music (Seigen Ono, Arto Lindsay…); architecture (among many, a recent project is Kazuyo Sejima [of SAANA] for Comme des Garçons [2009]); media (Visionaire 20 [1997], a “visual interview” with Kawakubo as the publication’s first guest editor; Vogue Nippon X Comme des Garçons Tokyo shop, featuring Chanel [2009]; A Magazine Curated by Jun Takahashi Undercover [2006]; Werk No. 10 in collaboration with Colette [2004]…); product and retail partnerships (Comme des Garçons X THE BEATLES with Apple Corps Ltd. [2009], Milan’s 10 Corso Como replica in Tokyo, Colette meets Comme des Garçons, the “Paris – Tokyo Speedconnexion,” H&M, Louis Vuitton…); creative direction (Christian Astuguevielle, the Comme des Garçons PARFUMS creative director since 1992; advertising conception with art director Tsugaya Inoue…); and tutti quanti…

Not only do Comme’s collaborations span many enthusiastically welcomed and established bodies of work in contemporary art and retail; they also include slightly unknown practices that seem to incarnate Kawakubo’s more personal fascinations. Illustrator Filip Pagowski created the PLAY CDG logo, and the highly-celebrated, successful commercial line has gone on to collaborate with many more illustrators and patternmakers. Kawakubo’s interest in documenting ethnic identities led to Brian Giffin’s photography of young Georgian women dressed in CDG in the birth village of the late primitivist painter Niko Pirosmani (1862–1918). Unearthing the work of female artists, both past and present, is also a mark of Comme and Kawakubo, and includes a joint effort with one of the first gild-bronze costume jewelry designers, Line Vautrin (1913–1997), as well as an homage to the French photographer and writer Claude Cahun (1894–1954). In 1992, Ndebele artist Esther Mahlangu created installations for Comme stores in Tokyo, Paris, and New York.

In 1988, Kawakubo launched her first stunt effort in print, Six magazine, which pushed the frontiers of art and fashion photography to spectacular results. The publication showcased extensive portfolios by leading photographers such as Peter Lindbergh, Paolo Roversi, Steven Meisel, and Timothy Greenfield Sanders, as well as multiple portraits and images by and of artists and designers, including Louise Nevelson, James Lee Byars, Gilbert & George, Azzedine Alaïa… As an ongoing extension of Six – and not even to mention CDG PAPER, which is distributed to the company’s staff worldwide – the house’s direct mailings always incorporate the power of art and visual culture. In 1994, Kawakubo wished Happy New Year to her merry followers with an image extract the Soviet-Armenian director Sergei Parajanov’s 1968 film, The Color of Pomegranates. An extension of the Mail art movement that originated in the 1960s? Potentially. But definitely a recurrent statement of the brand’s philosophy as a global communication vector.

And let us not forget the house’s fellow designers (Junya Watanabe, Tao Kurihara, Ganryu, and, to an extent, the “prodigal son,” UNDERCOVER’s Jun Takahashi) are freely expressing their personal vision through multiple labels inside CDG, as well as through retail. It starts and ends by being solely about mutual understanding and support, through which Comme des Garçons’ global label extends as a thinking method into a media of savoir-faire. This generosity brings not only economic power, but also new platforms of expression and diffusion to the label’s invited participants.

It’s all done for the simple love-value of the good, and for what simply has to be done. What is seen through and depicted in the eyes of Rei Kawakubo is cultural essor, and her edifying will to achieve is by now collective legacy.

CYRIL DUVAL (Item Idem) for 032c

“For me there’s no compromise, I do what I want, and they do whatever I couldn’t do myself.” Rei Kawakubo, W, September 2008.

COLOR

In Japan, Kawakubo’s early followers, dressed in head-to-toe BLACK, were popularly known as “the crows.”

In March 1988, Kawakubo resolutely declared: RED is black. She illustrated her point with a standout collection (A/W 1988) full of virulent red.

“Only someone such as Kawakubo, who has reached the deepest understanding of monotone, has such a feeling for colour and can create such a brilliant red.” Seiichi Minzuno in Deyan Sudjic, Rei Kawakubo and Comme des Garçons, 1990.

For the 7th issue of 032c, “At War With the Obvious” (Summer 2004), Kawakubo contributed five variations of blue based on the Pantone color code system. No text accompanied the plates. “The colour gold reminds her of “Dubai, of the Vatican and of teapots.”

Susannah Frankel, “Rei,” Another Magazine #18, Spring/Summer 2010.

“Throughout the 1980s, Kawakubo’s color palette was dominated by white, gray, and black, plus beige and navy. The theme of ‘darkness’ was omnipresent in her creations. Along with Yohji Yamamoto, she made black fashionable… Kawakubo’s use of black in the 1980s was so influential that she is still associated with the color. However, since she launched her red Autumn/Winter 1988 collection, black has nearly disappeared from her work. Moreover, Kawakubo’s color choices and combinations are at once radical and harmonious; she seems to have established her own chromatic sensibility. Kawakubo returns to black periodically. For her, black may not be just achromatic, but a ‘color’ in its own right.”

Fashion in Colors exhibition catalogue, Cooper Hewitt Museum, Smithsonian, New York 2006.

CREATION

“At Comme des Garçons, everything is connected by creation: clothing design, graphic design, interior design, business strategy, marketing. All these have their own causes and effects, and to bring them all together as one force, one image, is interesting but very difficult.” Rei Kawakubo in Menkes, 2009.

When we met in the 80s, that was a time when fashion distinguished itself with its creative muscle and while that’s diminished now, Rei remains an exception and a tour de force season after season. With Rei, she is all about the work, in the way that Michelangelo wouldn’t take his shoes off when he slept because he felt that time could be better spent painting – she’s in the same mold.

Gene Krell, Fashion Director, Vogue and GQ Japan, to 032c. Interview by Vicente Gutierrez.

“I really felt that I was on my own. I never felt my work had anything to do with being a woman. I am not a feminist. I was never interested in any movement as such. I just decided to make a company built around creation, and with creation as my sword, I could fight the battles I wanted to fight.” Rei Kawakubo in Lee Carter, “Connect the Dots,” T Magazine, August 28, 2005.

D

DESIGN

“In the Comme des Garçons fashion collections, Kawakubo has offered shirts with extra sleeves and neck holes, jackets cut to be misbuttoned, skirts and dresses with wildly irregular hemlines, jackets with slits up the length of the sleeve, jackets bearing only one shoulder, clothing with exposed seams, or asymmetrical padding in unconventional places, and knitwear with holes used to decorative effect: such clothes cannot be discussed in conventional fashion terms.”

Jessica Glasscock, “Bridging the Art/Commerce Divide,” Grey Gazette (exhibition booklet), Vol. 3, No. 1, New York University, November 1999.

“Ragged seams become ruffles. Yards and yards of ruffles. Ruffles appear in unexpected places poking out of seams. Holes in sweaters become gashes in the bodices of evening dresses. Jackets are dismantled and turned inside-out or put together in new ways. The inside of a cardigan becomes the outside with the bumpy texture of knitted roses close to the body. Or perhaps it is the other way around. One never knows.”

Brooke Hodge, “On the Work of Rei Kawakubo and Comme des Garçons”, Harvard University GSD, May 2000.

DESTRUCTION

Kawakubo titled an all-black collection from 1982 “Destroy”. It has become legendary.

“The cloth scars in the form of cuts, and the healing process in that of seams, bandages, belts and zippers … The silhouettes are tenderly presented and thus hide the vehemence of the intrusions that Rei Kawakubo makes on the normal way of tailoring dresses and suits… No one can destroy his own work more beautifully than the Japanese designer.”

Ulf Poschardt, “On the Nature of Destruction,” 032c #2, Summer 2001.

DOVER STREET MARKET

“Instead of setting up on the typical luxury shopping boulevards in London – the Kings Road, Bond Street and Mount Street – Kawakubo chose a corporate office space on a forgotten street in London’s Mayfair district, which must have been much cheaper. Since her arrival, other brands have followed suit and, Dover Street is now home to London flagships for Acne, APC and Vanessa Bruno.”

IMRAN AMED for 032c.

“The recent frenzied spate of museum building has seen unfortunate comparisons made between these cultural institutions and shopping malls. But I love malls the way I love museums. Comme des Garçons founder Rei Kawakubo’s Dover Street Market is rightly being described as the ultimate mall. Everything she thinks you should want is spread out over six floors. It is the most sublime, sensual shopping experience, carefully curated to include an Azzedine Alaïa boutique, a dozen Comme lines, and Terry de Havilland shoes. Dover Street is not the perfect mall; it is actually the perfect museum.” Thelma Golden, Director, The Studio Museum in Harlem, “Best of 2004: 13 critics curators look at the year in art,”Artforum December 2004.

“I want to create a kind of market where various creators from various fields gather together and encounter each other in an ongoing atmosphere of beautiful chaos: the mixing up and coming together of different kindred souls who all share a strong personal vision.”

Rei Kawakubo, www.doverstreetmarket.com

DISSENT

“The majority is always wrong”

Henrik Ibsen, “An Enemy of the People.” Printed on fabrics for Comme des Garçons men’s Fall 2003 collection.

E

ESSENCE

“Rei’s clothes have that weird mixture of Japanese minimalism and nihilism and Walt Disney”

Nick Knight, “Rei,” Another Magazine #18, Spring/Summer 2010.

EVERGREEN

CDG Homme Plus subline introduced in 2005, since discontinued, consisting of favorite items from past collections that have been re-issued with slight design alterations.

“I have one of these, trust me, they’re worth it! Their polyester fabric is very nice and comfortable and they do so many things with it, do it in a crisp twill, do a warped/wrinkled treatment, etc. I NEVER thought I would ever want to own anything polyester but I was suprised how much I like their synthetic pieces.”

Posted by brian_w in response to “$1,000 for a polyester jacket? I’m trying really hard to swallow this …” Posted by birdofparadise on The Fashion Spot online community, “Evergreen” thread.

F

FOUNTAINHEAD

“One cannot fight the battle without freedom. I think the best way to find that battle, which equals the unyielding spirit, is in the realm of creation. That’s exactly why freedom and the spirit of defiance is the source of my energy.”

Rei Kawakubu in Frankel, 2010.

FRAGRANCE

Since launching its first eponymous perfume in 1994, Comme des Garçons has steadily developed a small but significant line of innovative fragrances, many of them unisex. Over the years they have included such critically acclaimed and commercially successful scents as Comme des Garçons 2 and, most recently, Wonderwood. Odeur 53, the brand’s first “anti-perfume”, with cellulose and burnt rubber among other unconventional notes, was released in 1998 to mixed reviews. “Odeur 53 (Comme des Garçons)*** woody soapy

Historically important but artistically unsatisfying, this fragrance started as a minimalist one-line concept-art school of perfumery that has so far proved only a moderately good idea. This one was intended to smell clean and does that a million times better than the fragrances from the “Clean” brand which just smell vile. But it begs the eternal question: pour-quoi pas rien?” Luca Turin and Tania Sanchez, Perfumes: The Guide, Viking, 2008.

FREEDOM

“Feeling free inside oneself is being free.”

Rei Kawakubo, Interview Magazine, November 2008.

FUN

“I duly asked her what she laughs at, and she answered deadpan, ‘People falling down.’”

Thurman, 2005.

FURNITURE

Kawakubo has designed five collections of furniture. “Chair No. 1”, from 1983, was not characterized by comfort.

G

GATEWAY

Of all Comme des Garçons products, the classic zippered wallet is perhaps the single most sought-after item, even by people who know little else about the brand.

GONZALEZ-TORRES, FELIX

Candy Pieces by the Cuban-born artist was shown at the Aoyama store in May of 1998.

H

HISTORY

“Ms. Kawakubo, 66, is one of the great fashion forces from the last decades of the 20th century to now.“

Menkes, 2009.

“In fashion, it was the year of the Japanese. And no one in that ultra-sensitive land, where every stitch can set off an earthquake, rattled more sake cups than Rei Kawakubo – not even her talented compatriots Issey Miyake and Yohji Yamamoto. From Paris to Tokyo her followers are striding about in Kawakubo’s mournful, strangely cut garments, black socks and rubber shoes. Rei’s critics hold the 41-year-old designer responsible for perpetrating a formless, asexual look. ‘Her clothes don’t touch or mold the body,’ complains traditionalist French designer Sonia Rykiel. ‘There’s a lack of softness.’ But Rei’s supporters credit her with some of the most startling and influential designs out of Japan today.’Rei is an original,’ says Bendel Vice-President Jean Rosenberg. ‘She is a master of intricate cuts.” Kawakubo, the most radical of the new wave of Japanese designers, pronounces Western skintight garments ‘quite boring,’ adding, ‘I design for women who are beyond that.’ What sort of woman? ‘The bag lady of New York,’ Kawakubo replied fliply when asked by Women’s Wear Daily.

“Rei’s now historic advance on the West took place only two years ago. Her first show in Paris caused one of the biggest furores since Stravinsky introduced The Rite of Spring. Like Stravinsky, Rei coolly mocked conventions – shredding and poking holes in skirts, tops and dresses. In the US, where her clothes still baffle the uninitiated eye, Rei’s success is growing rapidly. She now has outposts in nine US cities, with her own boutique in Manhattan’s breathlessly fashionable SoHo district.’

“Japan’s Stravinsky of Fashion Rocks the World with her Atonal, Assymetric Sad Rags,” People Weekly, December 26, 1983.

Elsa Klensch: When did you first become interested in fashion?

Rei Kawakubo: When I was about 24. I’d been working in the adverstising department of a textile company, and I was asked to style the print ads and TV commercials. I liked the work so much that after two years I decided to leave the firm and work as a freelance stylist.

EK: Later, when you decide to become a designer, was it because you couldn’t find clothes you thought were right for your work?

RK: It wasn’t so much that I couldn’t find the kinds of clothes I wanted. I was frustrated by the way we chose the clothes.

EK: When and how did you get started?

RK: In about 1969 I rented a room that was part of a Tokyo graphics design studio and set up with two assistants.

EK: What sort of clothes did you produce?

RK: Clothes I felt were modern and new. But they were commercial as well; I was in business, and I had to support myself.

EK: How did you decide on the name Comme des Garçons?

RK: I don’t remember exactly. I know I wanted something long, something with a ring to it. One of the people working with me said, “How about ‘Comme des Garçons?’” And I thought, “Why not?”

EK: Your own name has a ring to it.

RK: I didn’t think of myself as a designer. It was a business, a group of people working together. I wanted a name that would represent the whole group.

Elsa Klensch, “Another World of Style … Rei Kawakubo,” Vogue (New York), August 1987.

KARI RITTENBACH: For a designer – or rather, aesthete – whose otherworldly ascent in fashion is accounted for by no less a creation myth than the flattest plateau of “starting from zero” (the uncouth postwar epithet “Hiroshima’s Revenge” attended CDG’s earliest presentations), it is certainly apposite to examine how Kawakubo allows herself to be historicized after the fact. A deconstructivist with a paradoxically tightly controlled image, Kawakubo toys with cultural and historical references as adroitly, or as murkily, as the most prodigious Postmodernist – and in so doing has fashioned a history all her own. But what came before the legend? What was the reception to early Comme des Garçons in Japan like during the seventies? (Kawakubo began producing clothing for CdG as early as 1969.) Does much clothing from this early period still exist? In her New Yorker profile of Kawakubo, writer Judith Thurman is best able to describe these pieces as possibly featuring “denim apron skirts.”

AKIKO FUKAI: For Kawakubo, the Seventies were, I could say, her training or trial period. She was well known among professionals, such as stylists, fashion journalists and buyers, who considered her a very talented new type of designer. In fact, we have just a few items of clothing from her earlier period. They are as Thurman described, and based mainly on “basic” daily clothes, such as Japanese traditional farmer’s clothes made of “Aizome” (Japanese indigo dye textiles or denim) and men’s tailored suits. They are baggy without holes and tiers – yet a flair for a new era can be discerned in her clothing.

What was women’s sportswear or streetwear like in the 1960s before Kawakubo?

So-called American sportswear had already been translated into Japanese women’s wardrobes in the 1960s. The Japanese apparel industry had developed enormously by learning the American ready–to-wear fashions around that time.

Was it more difficult for Kawakubo to control the presentation of her apparel as a young designer? (Which might necessarily have encouraged her to show in Paris?)

No, it was not. After having established her own company in 1969, she presented her first show in Tokyo in 1975 and opened her boutique at the same year. (I remember very well her first boutique. It was located on the second floor of a building in Minami-Aoyama, Tokyo and was discreet without a too nice welcoming-feeling but filled with a stimulating atmosphere.) Anyway, she debuted in Paris. It was unavoidable for her to present her works in Paris, the only place where her works might be judged properly, whether positively or negatively.

Kawakubo is a virtuoso of contradiction. The title of her women’s line is French for “like boys,” yet for all of her androgynous apparel, she has been careful to resist being labeled a feminist. Kawakubo also established herself squarely in an industry dominated by men. How were her early accomplishments viewed in Japan, and has it had any affect on gender politics in fashion there since?

In Japan before her, there were already several female fashion designers who had met with success in the business. For example, Hanae Mori was received as a member of Paris Haute Couture in 1978. The naming of her brand CdG is not related to feminism but more to the attitude that Kawkubo does not compromise on conventionality. She said, ”I try to create clothes by breaking away from the clothes (or thinking) that already exist” (“Deconstruction and Elegance,” interview by Akiko Fukai, Dresstudy, Vol, 24, [Fall 1993]). Therefore her accomplishment had little affect on gender politics in fashion. In any case, Japanese feminists didn’t pay so much attention to fashion.

Do you consider Kawakubo’s quasi-feminism, then, to be reflected in her designs for women, which drape and abstract the female body rather than reveal or sensualize it? Or is the “style” of Comme des Garçons apparel simply more culturally amenable to the domestic consumer? In other words, is her treatment of the body considered radical in Japan?

As I mentioned before, she is not a feminist. Therefore I think it would be incorrect if we read her designs in the context of feminism. Her design reflects the indigenous notion of Japanese clothing (the kimono, for example) that it is not necessary to obey the body’s form, in contrast to the Western notion that clothes should obey the body’s form; in other words, clothing has the autonomy. In the Japanese tradition, clothing tended to conceal the body line rather than reveal it. Therefore Kawakubo’s treatment of the body did not shock Japanese people. But what shocked them was her fervent and strong expression, through the dynamic volume of form, intricateness of construction and devotion to black in her clothing.

What is most appealing about Comme des Garçons to the domestic consumer? Kawaii (Kawaii contains a feeling akin to Japanese version of femininity). At the same time, the label’s very edgy and artistic quality.

In a 1983 interview with Women’s Wear Daily, Kawakubo insisted: “I’m not very happy to be classified as another Japanese designer. There is no one characteristic that all Japanese designers have.” How do you respond to this statement, today? I agree with what she said. She can be classified by her own characteristics but not as particularly Japanese. However I am sure that any creators – whether designers or artists – can’t escape from the influence of Zeitgeist on their works; the circumstances, the time, and of course the culture.

What do you consider Kawakubo’s relationship to history? Would it be wrong to question the veracity of her claiming a starting point of conceptual “absolute zero”? That later Comme des Garçons collections have riffed on countless historical references (Magritte’s The Red Model of 1935 or designs by Elsa Schiaparelli, for example) certainly indicates that fashion and art history – and not only contemporary culture, high or low – maintain a certain significance for her.

In fact in 1993, Kawakubo curated a small fashion exhibition entitled “Essence of Quality” by mixing KCI’s historical costumes with her works in Tokyo. As she said, “I can’t create without being inspired by nothing.” She knows about art history and fashion history. But in her work, the relationship to the history is ambiguous; it is not simply revisiting the past. She catches elements of inspiration with her sensitive antennae and absorbs them. Then she restores them to the level of “zero”, where her own creation starts.

Western journalists have used adjectives like “esoteric,” “severe,” “tricky,” “fervent” and “innovative” to describe Kawakubo’s influence on the world of fashion via Comme des Garçons. How have you generally described her aesthetic?

Stimulating, dynamic, strong, intricate, and new-feminine. The femininity of the new era has been created by Comme des Garçons following after Coco Chanel. New-femininity looks sometimes androgynous; it is not determined by men’s eyes.

AKIKO FUKAI, Chief Curator, The Kyoto Costume Institute, to 032c.

The KCI holds a total of 1500 CdG pieces from the early 1980s to today.

Interview by Kari Rittenbach.

HOME

Kawakubo owns an apartment in a modern tower on the edge of a cemetery, not far from Comme des Garçons’ headquarters and three stores in Aoyama. The apartment’s precise location is a secret.

HONORS

In 2000 Kawakubo was awarded the “Excellence in Design Award” from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design.

I

IDENTITY

“I came across Comme des Garçons in the early 1980s, a season or two after Rei Kawakubo first showed in Paris. At the time I was a trainee journalist with no money and still dressed by customising jumble sale bargains. But as soon as I could afford to, I started buying a piece from Comme each season. Fashion was much more politicised then, because feminism was so important. What you wore said so much about your own identity, and how you wanted to represent your gender. Comme was the perfect solution. Swathing yourself in those black folds felt super chic, super uncompromising, super radical and super feminist – like waving a very elegant two-fingered salute at the establishment.”

Alice Rawsthorn, “Rei,” Another Magazine #18, Spring/Summer 2010.

INFORMATION

“What is important to me is information (in the journalistic sense of relating news.) Through my collections, other product projects and through my graphic work, or by collaborating with artists and photographers, I like to tell a story. Without news, nothing is alive. The final result of everything must say something. Information deepens the work. So, if anything, I am maybe more of a journalist than an artist!” Rei Kawakubo in Menkes, 2009.

J

JOFFE, ADRIAN

Married to Rei Kawakubo since 1992, the South African is the president of Comme des Garçons International. He is the company’s main spokesperson and Kawakubo’s chief interpreter.

K

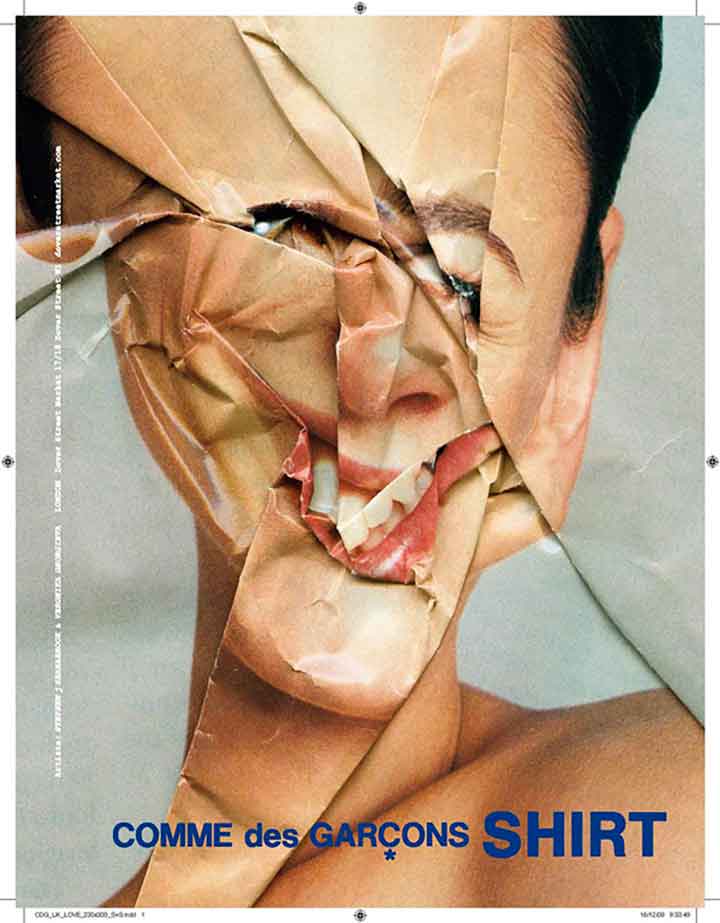

KISS

Models in the Comme des Garçons women’s Fall 2009 collection wore tulle masks embroidered with red sequins in the form of a lip smudge.

L

LOVELY

Kawakubo has said she starts out by giving form to ideas she considers “lovely” or “smart.”

M

MATERIALS

“Over the years the designer has also incorporated textiles thought to be cheap, ostentatious, cute, vulgar, or kitsch, and repositioned them in the aesthetic hierarchy.”

Koda, 2008.

- “It was Hiroshi Matsushita who devised the rayon criss-crossed with elastic that allowed Kawakubo to make the garments in the women’s collection of 1984 bubble and boil as though they were melting. And it was Matsushita who formulated the bonded cotton rayon and polyurethane fabric Kawakubo used for her asymmetric dresses of 1986 … For Matsushita, the distinctive character of a Comme des Garçons garment can be traced back to the thread that will be used to weave the fabric from which the collection will be made.“

- Once she gave us a piece of crumpled paper and said she wanted a pattern for a garment that would have something of that quality. Another time she didn’t produce anything, but talked about a pattern for a coat that would have the qualities of a pillowcase that was in the process of being pulled inside out. She didn’t want that exact shape, of course, but the essence is that moment of transition, of half inside, half out.”

Sudjic, 1990.

MEMORY, erased

“Continuity of tradition and history is present in varying degrees in all cultures, but learning to forget these rather than inheriting them is far from easy. In place of ‘forgetting’, we could substitute the words ‘destruction’ and ‘rebirth’. This is because in order to create a new memory, we must first erase the old memory. One of only a handful of examples where the mechanism of destruction and rebirth has been adopted in the context of handing down a tradition is the shikinen sengu ceremony at the Ise Shrine, according to which the shrine is completely dismantled and rebuilt every 20 years. The meticulousness with which this renewal ceremony is observed, which means that not only the buildings but everything down to the artefacts inside the buildings are replaced, results in the crystallization both of the skills of the craftsmen involved and of the time in which they act. A certain purity is also achieved as a result of this process. The old and the new appear to be the same, but because the cells themselves have been replaced, strictly speaking they are different entities. The primal spirit in the form of the object of worship housed inside is embodied in the design of the shrine.

“A shrine that remains forever 20 years old or less could be thought of as an analogy for someone who rejects maturity beyond childhood and is reborn over and over again in order never to attain adulthood. This isn’t the same as equating growth with the rejection of development, but entails forgetting by denying one after another the things that accumulate inside one. The only things allowed to accumulate would be practical skills and pure technology. As soon as one declares oneself an heir to, or destroyer of, history or tradition, one begins to age towards ‘adulthood’.

“A feature of the work produced by these creators, who could almost be described as ‘Ise Shrine-like’, is that they help extinguish and regenerate the cells and contaminated memory neurons of the people who set eyes on them. Kawakubo Rei and Sejima Kazuyo, whom I rate as two of the greatest creators alive today, both fall into this ‘cell regeneration’ category.”

Hasegawa Yuko, Chief Curator, Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, “The Art of Forgetting,” Art iT Magazine, Fall/Winter 2006.

MODERNISM

Kawakubo has always functioned as a modernist. Her fashion is serious, singular, sensitive, full of energy and it always makes impertinent demands on our feelings. She works only for the satisfaction of her own ideas, season after season. She has used the skills of her pattern-makers in Tokyo to attack and explore a variety of human conditions, including randomness, unreality, our literal and metaphorical burdens, and our complex ideas about eroticism and beauty. She makes us see these things in her fashion.

CATHY HORYN, fashion critic of The New York Times, for 032c

N

NEW

“I want to design clothes that have never yet existed”

Rei Kawakubo in Koda, 2008.

O

OFFICE

“The first thing you should know about the Comme des Garçons headquarters is that it occupies five floors of an ordinary office building on a busy road, each floor as drably functional as the next. Nothing to reveal here except its nothingness. There is no receptionist to greet you or to direct you to the appropriate floor. This would only be a problem if you were actually expected at Comme des Garçons, but very few people are welcomed there, and that also applies to family members. ’No husbands, boyfriends, wives, daughters – never,’ said Joffe. Which brings us to the second thing you should know about Comme des Garçons: it’s a very secretive place.”

Cathy Horyn, “Gang of Four,” The New York Times, February 24, 2008

P

PATTERN

Design assistants at Comme des Garçons are patterners, and as patterners they must develop a feel not only for shape and texture but also, more tryingly, for what Kawakubo is feeling at the start of a collection, whether she is “happy” or “angry,” sentiments she rarely communicates in any detail. As she once explained, “At the start, I am not exactly certain what I am thinking myself. It is guesswork with us.” What Kawakubo hopes to achieve from this open process is that the patterners will think more intuitively and come up with things that will surprise her. Horyn, 2008.

“When she uses these abilities as a springboard to think freely and radically, patterns from the basis of her work. ‘Patterns are design. Designing actually begins with patterns.’ The concept is conveyed to the pattern makers using simple drawings and the nuances of language. Each person’s interpretation comes back to Kawakubo, and an exchange develops from there.

Something made once is never made a second time. This unequivocal statement of intent was made clear at Comme des Garçons for Comme des Garçons 4, a show for Comme des Garçons employees put together in September at the company’s head office. Patterns for 93 garments that had previously been produced were displayed in the form of bold, black graphics in a space whose floor, walls and ceiling had been painted white. Each pattern had been made into a garment using neutral sheeting and displayed on a mannequin torso placed next to the corresponding pattern. Set against a stark white background in a style reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s dance step paintings, the bold graphics seemed to borrow heavily from the pop/conceptual art form. Combined with the almost unbelievable variation of the forms standing like monotone statues in the spaces between the graphics, this resulted in a show that was extremely sophisticated and powerful.

But there was no so-called message or ideological theme there. The entire show consisted of displays of patterns, which take shape only after a process in which Kawakubo gropes around in an effort to come up with forms, relying for guidance on the most primal aspect of her work – the images in her head – and of the three-dimensional entities to which these two-dimensional patterns had given rise.

This approach of pursuing to an extreme the autonomy of the garment rather than fitting it to the body finds its ultimate expression in the bold pattern experiments and endless studies of the pattern makers. Because the actual form of the pattern is not bound by any conventions such as having to cut along the grain of the fabric, the garment develops a shape all of its own. This puts the onus on the person wearing a Comme des Garçons garment in the sense that it tests their ability to make the clothes look good on them.

The overall image depends on the experimentation with the form and the development of the patterns rather than the production of the three-dimensional garments on which they are based. For example, when one sees ‘Ultra-simple’ (October 1992), which despite the garments themselves being varied and complex in the extreme, is a quest by the designer to see how many clothes can be made using a minimum of patterns, one realizes that Kawakubo’s concept image is not found on the surface of the clothing, but at deeper level.”

Hasegawa Yuko, Chief Curator, Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, “The Art of Forgetting,” Art iT Magazine, Fall/Winter 2006.

PEERLESSNESS

There are few women who have exerted more influence on the history of modern fashion, and the most obvious, Chanel, is in some respect her perfect foil: the racy courtesan who invented a uniform of irreproachable chic and the gnomic shaman whose anarchic chic is reproach to uniformity. They both started from an egalitarian premise: that a woman should derive from her clothes the ease and confidence that a man does. But Chanel formulated a few simple and lucrative principles, from which she never wavered, that changed the way women wanted to dress, while Kawakubo, who reinvents the wheel – or tries to – every season, changed the way one thinks about what a dress is.”

Thurman, 2005.

PHOTOGRAPHY

“It was a Harper’s Bazaar layout that precipitated (Cindy Sherman’s) collaboration with Kawakubo. After seeing that layout in 1993, Kawakubo contacted Sherman and provided her with clothing from each of the Comme des Garçons collections, to be photographed however Sherman wished. The resulting images were then used in the direct-mail campaign for the Comme des Garçons autumn/winter 1994–95 collections and also displayed in the company’s SoHo boutique. These photographs are less depictions of saleable product than challenges to the expectation of what a fashion photograph should be, breaking virtually every rule of fashion photography.

“It was a Harper’s Bazaar layout that precipitated (Cindy Sherman’s) collaboration with Kawakubo. After seeing that layout in 1993, Kawakubo contacted Sherman and provided her with clothing from each of the Comme des Garçons collections, to be photographed however Sherman wished. The resulting images were then used in the direct-mail campaign for the Comme des Garçons autumn/winter 1994–95 collections and also displayed in the company’s SoHo boutique. These photographs are less depictions of saleable product than challenges to the expectation of what a fashion photograph should be, breaking virtually every rule of fashion photography.

As philosopher Roland Barthes has observed, fashion photography is generally governed by a garment-photograph-caption formulation, an apt description that cannot, however, be applied to Shermans interpretation of Comme des Garçons clothes. Her photographs center on disjointed mannequins and bizarre characters, forcing the clothing itself into the background. The lithe, physically ideal fashion model, so integral to the pages of Vogue, Glamour, and Elle, is nowhere to be seen. In her place are a menagerie of confrontationally unpretty surrogates, like the garishly made-up mannequin in Sherman’s Untitled (#302).

In the context of Kawakubo’s destabilizing approach to the established way of doing business in the fashion industry, her collaboration with Sherman, whose work also undermines the reality of particular images, seems almost predestined.”

Glasscock, 1999.

PLACE VENDOME

Number 16, Paris 1st Arrondisement: World Headquarters of Comme des Garçons outside of Japan since 1981.

PROTEGE

Tao Kurihara, own line under CDG umbrella since 2005

Junya Watanabe, own line under CDG umbrella since 1993

Fumito Ganryu, own line under CDG umbrella since 2007

Q

QUASIMODO

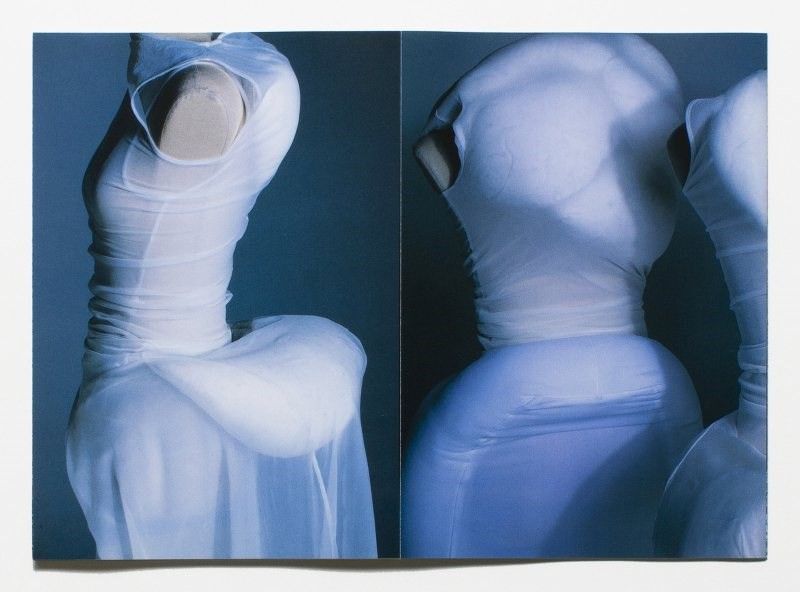

In October of 1996, Comme des Garçons presented its collection for spring/

summer 1997, titled “Dress Meets Body”. It is the most discussed Comme des Garçons collection to date, brought up in almost every interview, text or conversation about the label and its founder.

“The small invited audience sits in a square in the Musée d’Art Afrique et d’Océanie in Paris … There is no music and no catwalk. The first model comes on in a slender, white, semi transparent dress with two little buds at the back, like nascent angels’ wings. As the show progresses each model comes out in increasingly larger and, to most commentators, odder swellings, all under long, fitted dresses in stretch fabrics. Some are in red, white, or blue; others in a range of ginghams: black, pale blue, pink, or red and white. All are padded, with goose-down fillings. The feather pads are arranged asymmetrically; they run over a shoulder, diagonally across a hip, down the back, or coil round the torso, to form half-bustles, raised necks, or prominent backs. It is hard to find the words to describe the effect of these down pads under sheer dresses: if words fail perhaps it is because the dresses do not engage with the everyday language of the fashion body. ‘To make a form in which a woman looks pretty in a conventional way is not interesting to me at all,’ says Comme’s designer Rei Kawakubo. And it is true that she does not emphasize its conventional assets: small waist, flat stomach, curving hips and bottom, small, high breasts. Yet neither does she deny them particularly, even when she obscures some of these body parts. This is not a collection which engages tyrannically with fashion, and its requirements that the body be honed, exercised, produced. It seems, instead, to be a speculation on what else the body could be, other than.” Caroline Evans, “Paris 1996,” 032c #4, Winter 2002/03.

“Kim Novak’s protuberances in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Godzilla pores, pus flowering on top of pimples, nineteenth-century bustles and false fronts, Veronica Cartwright’s bug-eyed expression of horror in Ridley Scott’s Alien, prosthetic cocks or a ‘real’ erect one, cellulite and diagrams on how to combat it, the male/female character in Silence Of The Lambs regarding his image in the mirror, dick tucked between his legs – all these tabulae non rasae sprang to mind as I watched models garbed in Rei Kawakubo’s Spring/Summer ’97 collection walk down the runway this fall, their backs, shoulders, and hips made ecstatically, imagistically associative by the down humps planted in Kawakubo’s wool, polyurethane, and organdy gowns.” Hilton Als, “Bump and Mind,” Artforum, December 1996.

One of my favorite fashion moments of all times is, for different reasons, Rei Kawakubo’s “Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body” collection from 1996. At the time, I was in Paris doing an internship for Thierry Mugler; it was the season when Mugler and Gaultier did their first haute couture shows, and Galliano did his first Dior show and McQueen did his first collection for Givenchy. It was also the time when that Comme des Garçons collection was hanging in the CDG shop in Paris, not the new one, but the one at Etienne Marcel – I love that shop so much, and I loved the smell of it, it smelled like Comme des Garçons, the first perfume. And while it was really great to work at Mugler and get to look at all that great Parisian fashion, seeing Comme des Garçons was special because it was so different. Imagine, to be surrounded by haute couture and then go to Comme des Garçons and see all those weird clothes and those amazing skirts in paper and all the shapes and the colors, like little bulbs made of what had to be polyester in orange and turquoise. And you could try these things on – it was amazing. Even the simplest pieces; I remember this black T-shirt that just had like a bulb protruding on one side. Every time I think about it, I regret not having bought anything, because the clothes were relatively not that expensive at the time. And I know that even now, 14 years later, if I went to any party wearing that T-shirt with a bulb, it would be something. That collection will always be great.

LUIS VENEGAS, Creative Director and Publisher, EY! Magateen, Fanzine 137 & Candy, for 032c

“This season, Ms. Kawakubo might have pushed the hand-picked audience of supporters a bit too far. There is a delicate balance to her Comme des Garçons admiration society. Most important each season is her concept, which this time was ‘body meets dress, dress meets body and becomes one.’ But typically she throws a bone to those who still believe clothes are for wearing outside fashion focus groups without being gawked at. “This time there wasn’t much for this contingent. Ms. Kawakubo was experimenting with new forms and new bodies. So beneath beautiful stretch-fabric dresses she stuffed lumpy masses that looked a bit like collagen injections run amok. Shaped like kidney beans, sometimes they sprouted above the breasts. Sometimes they ballooned out of the back. Hamish Bowles, the European editor of Vogue, suggested that the clothes looked like something from ‘The Piano’ as if costume details like bustles had been interpreted by the Maori tribe. But others were less kind. At one point, as a model emerged, her shoulders stuffed, a photographer yelled out ‘Quasimodo’ into the deathly silent presentation, with no music and certainly no chatting. If the pads were removed, of course, there would have been painfully pretty layered stretch dresses with high necks, in colors like lavender and gray, or modern prints of melded watery colors, pale green, yellow, orange and pale blue. But mostly the dresses invented whole new deformities for women. The only mass with a positive connotation was one that jutted from the front like a pregnant body. There were some lovely dresses within the show, equally as conceptual and equally unwearable, some big bubbles that rose up from the hips so the model became an unopened flower, some giant swaths of red fabric that rendered models virtually immobile, and some that had skirts resembling waxed brown paper bags with big, bright jackets of what looked like crinkled crinolines. Ms. Kawakubo said she was looking to the future, and it’s true that ideas she started in the past – deconstruction, for instance – were hard to get used to. So, years from now, perhaps it will seem remarkable that these new shapes met resistant eyes, but it is highly unlikely.”

Amy Spindler, “Is It New and Fresh or Merely Strange?”, The New York Times,

October 10, 1996.

R

REI

“In person, the designer is as difficult to pin down as her clothes.” Frankel, 2010.

“People have the wrong idea about her, she’s not hard at all – she’s a gentle soul who loves old trees and cats and dogs… and big fat diamonds!” Adrian Joffe in“Anti-fashion Designer,”

The Star Online, Malaysia, July 11, 2004.

REI-ISMS

“A collection is never not an exercise in suffering.”

“What doesn’t sell today, sells tomorrow.”

“For something to be beautiful, it doesn’t have to be pretty.”

“Clothes are my views.”

REFUSAL

“There may be many reasons why Kawakubo resists verbal communication – one might attribute it to a deep mistrust of members the press who, let’s face it, were plain antipathetic when she started out or, simply to the fact that the designer may well just be shy.” Frankel, 2010.

- Said to have been exploring the boundaries of malleable form in movement with padded bumps at bust, rear, and midriff combined with a stretchy synthetic gingham, Kawakubo has never verbally confirmed a frustration with fashion’s passion for fit, even emaciated models and mannequins.”

- “Kawakubo, who has been labeled melancholic for her early use of black, has declined comment on these criticisms and allegations.”

The Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (www.metmuseum.org/toah)

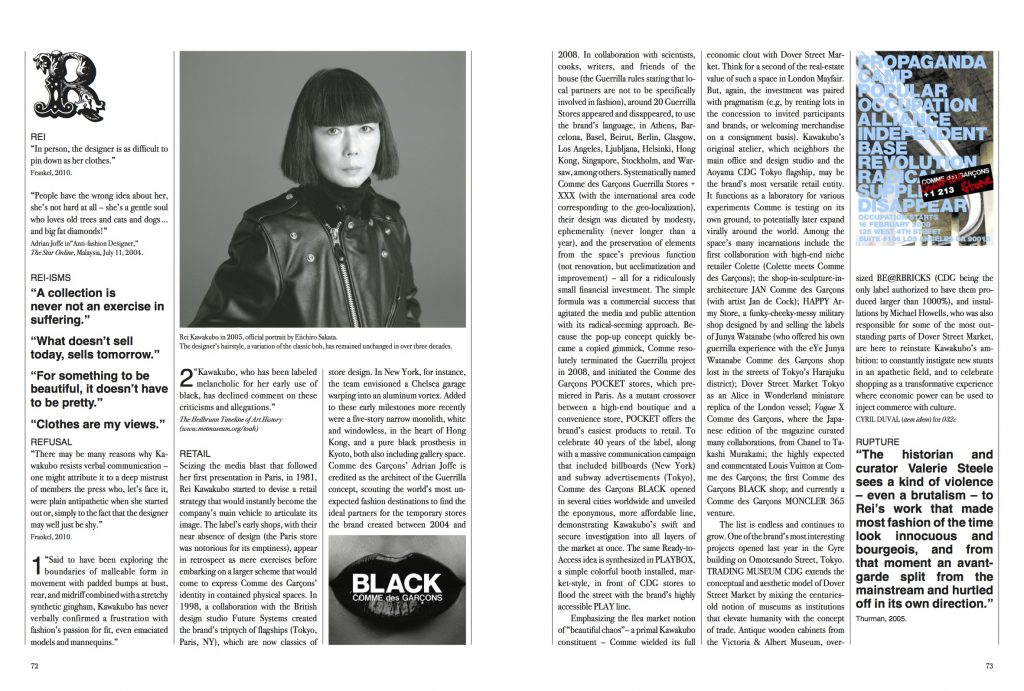

RETAIL

Seizing the media blast that followed her first presentation in Paris, in 1981, Rei Kawakubo started to devise a retail strategy that would instantly become the company’s main vehicle to articulate its image. The label’s early shops, with their near absence of design (the Paris store was notorious for its emptiness), appear in retrospect as mere exercises before embarking on a larger scheme that would come to express Comme des Garçons’ identity in contained physical spaces. In 1998, a collaboration with the British design studio Future Systems created the brand’s triptych of flagships (Tokyo, Paris, NY), which are now classics of store design. In New York, for instance, the team envisioned a Chelsea garage warping into an aluminum vortex. Added to these early milestones more recently were a five-story narrow monolith, white and windowless, in the heart of Hong Kong, and a pure black prosthesis in Kyoto, both also including gallery space. Comme des Garçons’ Adrian Joffe is credited as the architect of the Guerrilla concept, scouting the world’s most unexpected fashion destinations to find the ideal partners for the temporary stores the brand created between 2004 and 2008. In collaboration with scientists, cooks, writers, and friends of the house (the Guerrilla rules stating that local partners are not to be specifically involved in fashion), around 20 Guerrilla Stores appeared and disappeared, to use the brand’s language, in Athens, Barcelona, Basel, Beirut, Berlin, Glasgow, Los Angeles, Ljubljana, Helsinki, Hong Kong, Singapore, Stockholm, and Warsaw, among others. Systematically named Comme des Garçons Guerrilla Stores + XXX (with the international area code corresponding to the geo-localization), their design was dictated by modesty, ephemerality (never longer than a year), and the preservation of elements from the space’s previous function (not renovation, but acclimatization and improvement) – all for a ridiculously small financial investment. The simple formula was a commercial success that agitated the media and public attention with its radical-seeming approach. Because the pop-up concept quickly became a copied gimmick, Comme resolutely terminated the Guerrilla project in 2008, and initiated the Comme des Garçons POCKET stores, which premiered in Paris. As a mutant crossover between a high-end boutique and a convenience store, POCKET offers the brand’s easiest products to retail. To celebrate 40 years of the label, along with a massive communication campaign that included billboards (New York) and subway advertisements (Tokyo), Comme des Garçons BLACK opened in several cities worldwide and unveiled the eponymous, more affordable line, demonstrating Kawakubo’s swift and secure investigation into all layers of the market at once. The same Ready-to-Access idea is synthesized in PLAYBOX, a simple colorful booth installed, market-style, in front of CDG stores to flood the street with the brand’s highly accessible PLAY line.

Emphasizing the flea market notion of “beautiful chaos”– a primal Kawakubo constituent – Comme wielded its full economic clout with Dover Street Market. Think for a second of the real-estate value of such a space in London Mayfair. But, again, the investment was paired with pragmatism (e.g, by renting lots in the concession to invited participants and brands, or welcoming merchandise on a consignment basis). Kawakubo’s original atelier, which neighbors the main office and design studio and the Aoyama CDG Tokyo flagship, may be the brand’s most versatile retail entity. It functions as a laboratory for various experiments Comme is testing on its own ground, to potentially later expand virally around the world. Among the space’s many incarnations include the first collaboration with high-end niche retailer Colette (Colette meets Comme des Garçons); the shop-in-sculpture-in-architecture JAN Comme des Garçons (with artist Jan de Cock); HAPPY Army Store, a funky-cheeky-messy military shop designed by and selling the labels of Junya Watanabe (who offered his own guerrilla experience with the eYe Junya Watanabe Comme des Garçons shop lost in the streets of Tokyo’s Harajuku district); Dover Street Market Tokyo as an Alice in Wonderland miniature replica of the London vessel; Vogue X Comme des Garçons, where the Japanese edition of the magazine curated many collaborations, from Chanel to Takashi Murakami; the highly expected and commentated Louis Vuitton at Comme des Garçons; the first Comme des Garçons BLACK shop; and currently a Comme des Garçons MONCLER 365 venture.

The list is endless and continues to grow. One of the brand’s most interesting projects opened last year in the Gyre building on Omotesando Street, Tokyo. TRADING MUSEUM CDG extends the conceptual and aesthetic model of Dover Street Market by mixing the centuries-old notion of museums as institutions that elevate humanity with the concept of trade. Antique wooden cabinets from the Victoria & Albert Museum, oversized BE@RBRICKS (CDG being the only label authorized to have them produced larger than 1000%), and installations by Michael Howells, who was also responsible for some of the most outstanding parts of Dover Street Market, are here to reinstate Kawakubo’s ambition: to constantly instigate new stunts in an apathetic field, and to celebrate shopping as a transformative experience where economic power can be used to inject commerce with culture. Cyril Duval (item idem) for 032c

RUPTURE

“The historian and curator Valerie Steele sees a kind of violence – even a brutalism – to Rei’s work that made most fashion of the time look innocuous and bourgeois, and from that moment an avant-garde split from the mainstream and hurtled off in its own direction.”

Thurman, 2005.

S

SALVAGE

“Rei used to love going through the garbage to find things we’d thrown out – now I bring our garbage can with us.” Ronnie Cooke Newhouse in Rawsthorn, 2009.

SCENARIO

On October, 14 1997, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company premiered Scenario at the Brooklyn academy of Music. The dancers were wearing costumes designed by Rei Kawakubo.

“The costumes stole the show. The first, colorful section suggested a tropical utopia, an undiscovered island of weird cultural signifiers, of Others dancing away. When the dancers came out in their black Kawakubos, I thought of French poodles groomed for show; or Victorian widows, their bustles askew; or the precarious black hair-buns of geishas; or Dior’s New Look, with its fertility goddess swells. I had not considered just how ubiquitous bumps and humps are in fashion history, how natural to the landscape of artifice. Nor had i ever seen the Cunningham dancers look glamorous in quite this way – in a fashion context. The women’s strong, slim, lower legs were suddenly gorgeous, feminine legs – eroticized. Gams.” Laura Jacobs, “Computer games: Merce Cunningham,” The New Criterion, December 1997.

SECRECY

“The quest proceeds behind closed doors, like a papal election, and successive meditations on the koan produce more or less adequate results.”

Thurman, 2005.

SEX

Falling somewhere between an amish smock and a Coogi sweater on the hotness scale, Comme des Garçons is, without a doubt, the least sexy of any fashion label today. More platonic than erotic, more comical than come-hither, the clothes simply do not hug a woman’s curves in the way French designers do or leave the flesh bare in the way Italian designers do. They don’t even subliminally echo, suggest or point to a person’s naughty bits. “Like boys,” it would seem, is just a name.

Not even when Rei Kawakubo began showing her collections in Paris in 1981 did her designs become any more titillating or romantic. While suggestive, the spring 1997 collection known as “lumps and bumps” (ascribed by the press) was more about bodily extremes than carnal desire. And the Rolling Stone tongue-and-lips prints of the spring 2006 men’s collection was less about male libido than riffling on a trademark. No, to this day the Comme des Garçons look has more to do with its original inspiration, rustic Japanese peasantry, than a romp in the hay. But let’s be clear. It isn’t that Ms. Kawakubo takes a clutch-pearls, Victorian view on sex. It’s as if the subject doesn’t ever enter her thought process.

Not even that most sensuous of designer offerings, the perfume, is remotely arousing when it comes from the Comme des Garçons camp. Among its best-sellers, odeur is in fact an “anti-perfume,” and touted as such. With notes that include nail polish and burnt rubber, it’s a far cry from the pretty florals, sweaty musks, and pheromone-laden wannabe aphrodisiacs on the market. Perhaps there is a sexual innuendo in the more recent fragrance, Wonderwood, but it’s doubtful.

Only two Comme des Garçons advertisements have ever come to my attention. One was for PLAY, a secondary line, and the other a fragrance. But even if Comme advertised its scents as heavily as Dolce & Gabbana or Roberto Cavalli do, you would never, ever see a windblown, spread-eagled, airbrushed model draped in a near-orgiastic state over shirtless, swarthy men. Of this you can be sure.

So, okay, sex is off-limits in the Comme des Garçons universe. Which is to say, of course, that Comme, that most ironic of labels, is utterly, unequivocally, impossibly sexy.

LEE CARTER, Founder and Editor in Chief, Hintmag.com, for 032c

SIX

“Begun in 1988 and published biannually, that is, for the Spring and Fall collections of Comme des Garçons, Six was never intended to be merely a means of itemizing what was for sale, that much is clear. Large format (15.5 x 11.5) of folded loose leaves, it is not a pocket book! Its format imposes a presence and physicality upon the reader or viewer, since each issue is much more a folio of photographs and collage in performance than a picture book of pretty glossy snaps, hence the preference for black and white (rather than color) as though in line with art house black and white film. It brings an approach to content and style that is wholly avant-garde: beginning with the (relative) use of anonymity in order to facilitate the sense of the review as a collective creative endeavor; the fact that the journal is given away free to all interested parties (a form of potlatch, then); the range of materials and subjects brought together: furniture, photography, fine arts, poetry, architecture and urbanism, portraiture, clothing; the recovery of out-of-the-way materials (the photographs of the people, landscape and folkart of Georgia, for example, a sort of contemporary Pont-Aven of the Gauguin and Nabis symbolistes; of the Surrealist-inflected photography of André Kertész along with the Constructivist cinema of Dziga Vertov), and all of this in the presentation of a view (an image) of living as integrated phenomenon, above all, the way in which these materials are brought together to make of the journal Six a laboratory of ideas, ideas which will then take on a life of their own in different forms (lines in furniture, clothing, interior architecture, photography, no less than dance in at least one case).”

Michael Stone-Richards, “I am a Cat,” Refusing Fashion, MoCaD 2008.

“From 1988 to 1991, Kawabuko embarked on a bold experiment that transformed the notion of a fashion catalogue from a documentary listing of individual items into a bold, avant-garde fine arts magazine that incidentally included images of the season’s line. She called the publication Sixth Sense, or Six for short, explaining in the premier issue, ‘”Six” is the sixth sense. It is the sense of the surreal. Although the sixth sense is impossible to describe, “flair” may be one aspect of this sense.’ Each issue mixed newly commissioned works by the hottest contemporary fashion photographers showcasing Comme des Garçons wardrobe with iconic images created by the masters of photography. Contemporary artists frequently appeared in the issues, both with their art and as models. The overall gritty quality of the prints is evocative of Kawakubo’s design aesthetic, which in the early days of the company was considered ‘Hiroshima chic.’”

Abstract from library catalogue, Sterling and Francine Clark art institute.

SPACE

“Her clothing is not so much about the body as the space around the body and the metaphor of self … the garment as a construction in space, essentially a structure to live in.”

Sarah Bodine, “Kawakubo, Rei,” www.fashionencyclopedia.com

‘Kawakubo’s clothes are architectonic or sculptural, concentrating on structure rather than surface. The garments are constructed and assembled, rather like a building, and because they are almost always spatial in nature they require a body to inhabit them, to supply the missing volume – often they are inconceivable without the body and, for this reason, are often much better off the rack and on the body.’ Hodge, 2000

T

TASTE

“I played with notions of bad taste and then did them the Comme des Garçons way. Of course, bad taste done by Comme des Garçons becomes good taste.”

Rei Kawakubo via The Fashion Spot, 2008

TYPEFACE

“It’s fashion’s first non-logo, it captures Comme’s spirit of complicated simplicity.” Paola Antonelli, Design curator, The Museum of Modern art, NY, regarding the font, with a star instead of a cedilla, that is the company’s de-facto logo.

“The World’s Top 50 Logos”, The Globe and Mail (Toronto), October 27, 2000

U

URBANISM

“Let it be said that Kawakubo’s enterprise has an urbanism. Prada has locations, many of them urban, but it doesn’t have an urbanism. Comme des Garçons is never on the main street of the most obvious shopping neighborhood. When Kawakubo established stable and proper showrooms, they tend to be invisible from the street – polka dot curved glass is inset from the building line, windows are spare and lack the loud broadcasting design of traditional storefront display and tunnels, and other kinds of passageways are constructed to keep the destination itself always at bay. Of course the guerilla stores – moving around like nomads or squatters who adopt places as they are found – take this urban principle and put it into action. If most stores today simply make static urban monuments, Comme des Garçons is an active urbanism of stealth and evasion, where shops walk around the world like updated flaneurs who can find privacy and secrecy only when exposed and in the midst of the chaotic city.”

Sylvia Lavin, “Pas Comme des architectes,” Refusing Fashion, MoCaD 2008.

URINE

In September 1994, Comme des Garçons introduced its first perfume. It was presented as a urine-yellow liquid in plastic bags laid out around the swimming pool at the Ritz Hotel in Paris. The fragrance’s concept was “WORKS LIKE A MEDICINE, BEHAVES LIKE A DRUG.”

V

VEHICLE

“Despite her wealth, her only apparent major indulgence is a vintage car, a monster Mitsubishi from the 1970s, which attracts the kind of stares in Tokyo that her clothes attract in Houston.”

Thurman, 2005

W

WEIWEI, AI

Concurrent to his sunflower seed installation at Tate Modern, Dover Street Market sells T-shirts by the Chinese artist for £15.

WORD

“I start every collection with one word, i can never remember where this one word came from. I never start a collection with some historical, social, cultural or any other concrete reference or memory. After I find the word, I then do not develop it in any logical way. I deliberately avoid any order to the thought process after finding the word and instead think about the opposite of the word, or something different to it, or behind it.”

Rei Kawakubo in Horyn, 2008.

WORK

Elsa Klensch: “What personality traits have contributed most to your success?”

Rei Kawakubo: “It’s not personality. It’s hard work. When Estée Lauder accepted her achievement award at the Fashion Group last fall she said she didn’t get where she got by chance. She worked. It’s the same with me. I worked hard every day. That’s all it is – a lot of hard work.”

Klensch, 1987.

X

XY/XX

Comme des Garçons, “like boys”: it’s been a gender game from the beginning. Girls who are boys who like boys to be girls… A graphic upending of sartorial orthodoxy in which the image of a man in a skirt is essential, because of the questions it poses about tradition, perception, aesthetics, and gender – or so it seems. But nothing is ever what it seems with Rei Kawakubo – and so it is with a man in a skirt. Walter van Beirendonck, a designer Rei Kawakubo happens to admire, once said, “When it is properly balanced, a skirt is without gender,” and, “Whether clothes are for men and women is all in the head.” Rei’s head is clear of preconception. Comme des Garçons integrates traditional elements of menswear and womenswear in the most matter-of-fact manner. Just how matter-of-fact becomes clear when you look at the ways other designers have proposed skirts for men: subversive, or provocative, or sexual, or aggressive, or satirical. There is none of that in the sight of Cole Mohr marching down the Comme catwalk in an ensemble that marries the monochrome rigor of clerical gear with the strictness of an Edwardian governess. But these are my preconceptions, not Rei’s. The two greatest influences on the evolution of the silhouette and attitude of contemporary Japanese fashion are Edwardian England and Vivienne Westwood. Rei Kawakubo mirrors both, the disciplined ego of one, the unleashed id of the other. But what really defines her interpretation is the notion of a kind of transcendent tribalism: indigenous Japan finding primal kinship with the Celts. it is also transcendent in that it rises above prosaic categorizations to explore a post-gender universality. So “comme des garçons” is ultimately also “comme des filles”. No wonder Rei’s clothes are increasingly knotty. They’ll take centuries to untangle.

Y

YAMAMOTO, YOHJI

The designer and Rei Kawakubo were a couple from the Seventies till the early Nineties.

Z

ZERO

“Collection after collection, Kawakubo obliterates her past.” Koda, 2008.

Credits

- Edited by: SULEMAN ANAYA and JOERG KOCH