Who the fuck is Vaquera?

|AGNES MAGGIE SHU

It was a happy accident when Patric DiCaprio drunkenly bought a sewing machine off the internet and taught himself how to sew via YouTube.

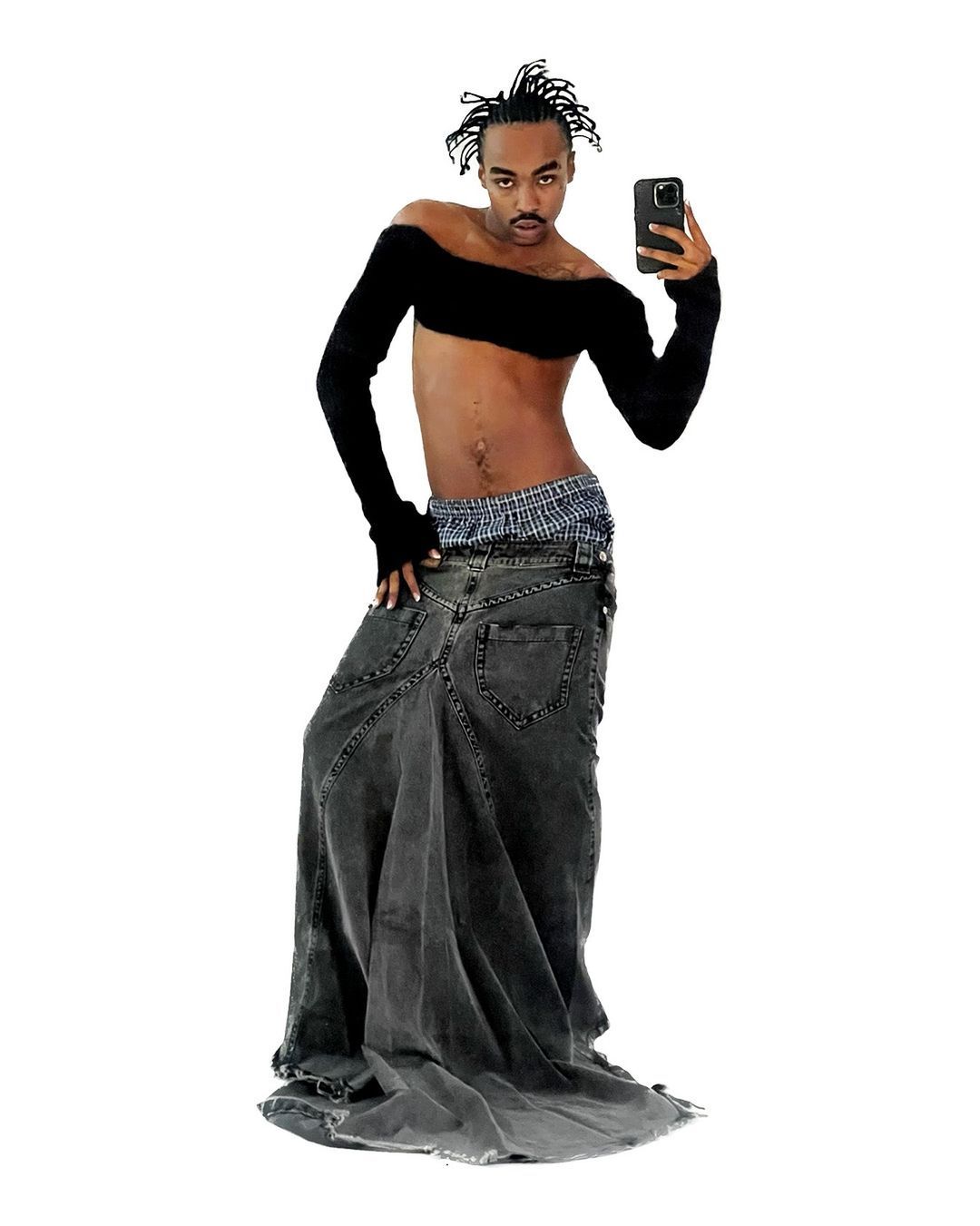

Out came Vaquera, a brand born out of this DIY approach to fashion and relentless referencing to past icons in tandem with present-day tropes. Under the direction of DiCaprio and Bryn Taubensee, Vaquera first appeared on Tumblr in 2013, using the platform to present their collections. While initially faced with criticism for “appropriating” their heroes such as Miguel Adrover or Martin Margiela with such overt references (in the early days, copy-pasting a whole Chanel look and slapping the Vaquera logo on top), Vaquera has proven to be an example of the future nostalgia trend, except that they don’t pretend to hide it.

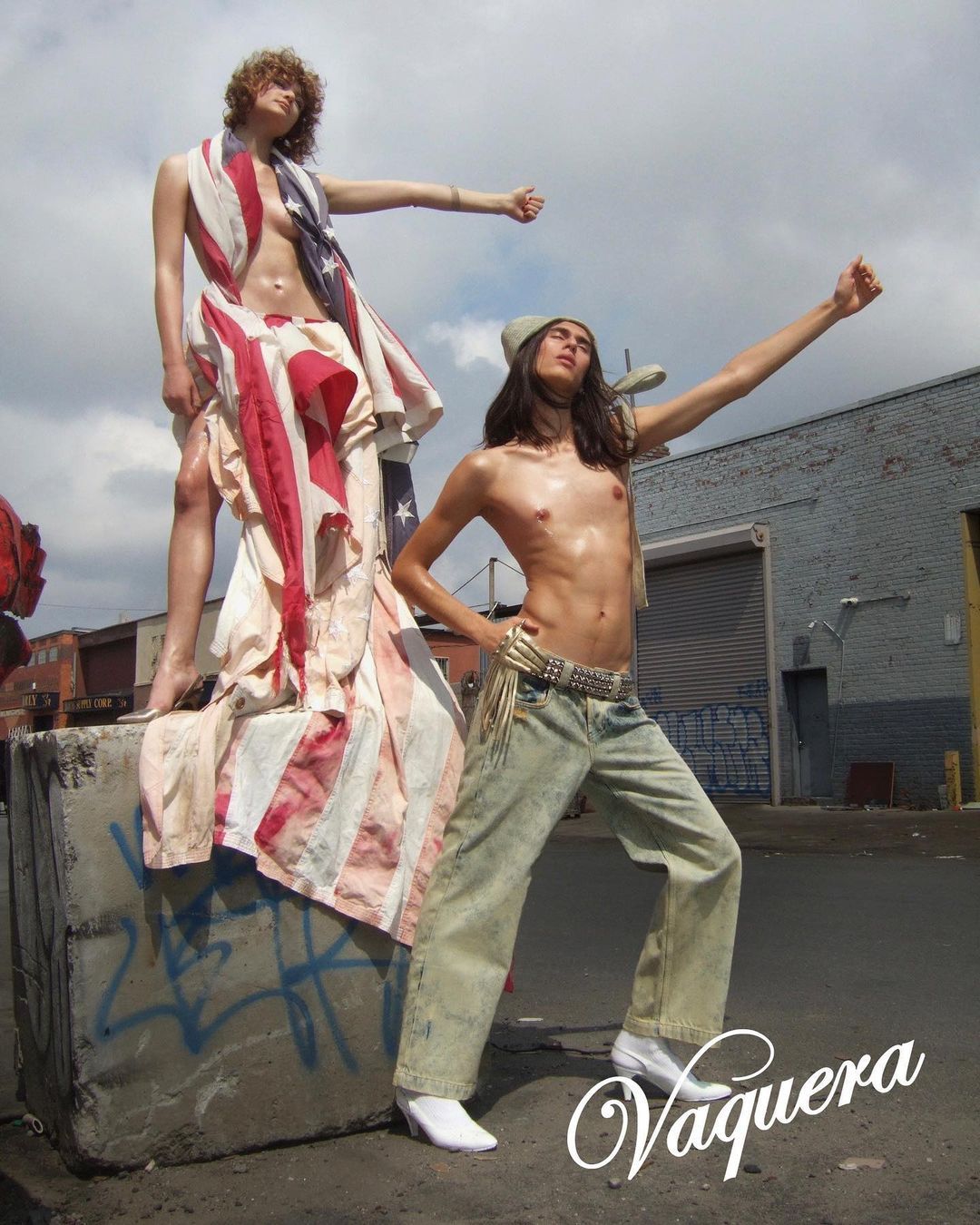

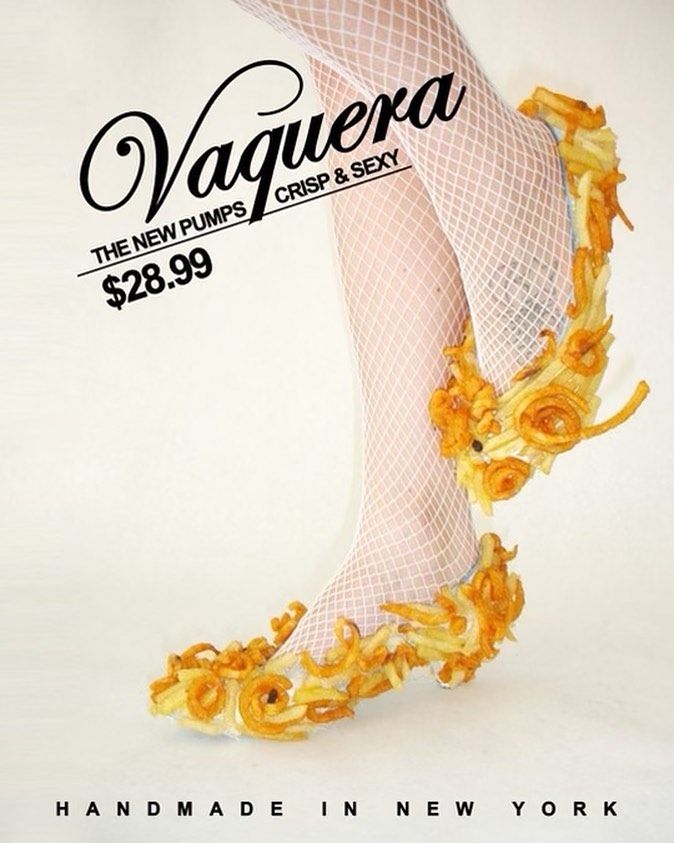

With an official Pornhub collaboration in 2024 and unofficial Tiffany & Co. thong in 2017 (one that Diet Prada was quick to post), one might mistake Vaquera for trolling the industry. But that wouldn’t do them justice. Alongside their quintessential American essence (sometimes so literal as to be a deconstructed American flag debutante dress), Vaquera belonged to the golden age of 2010s downtown New York fashion, alongside contemporaries in Ekhaus Latta, Telfar, and Opening Ceremony.

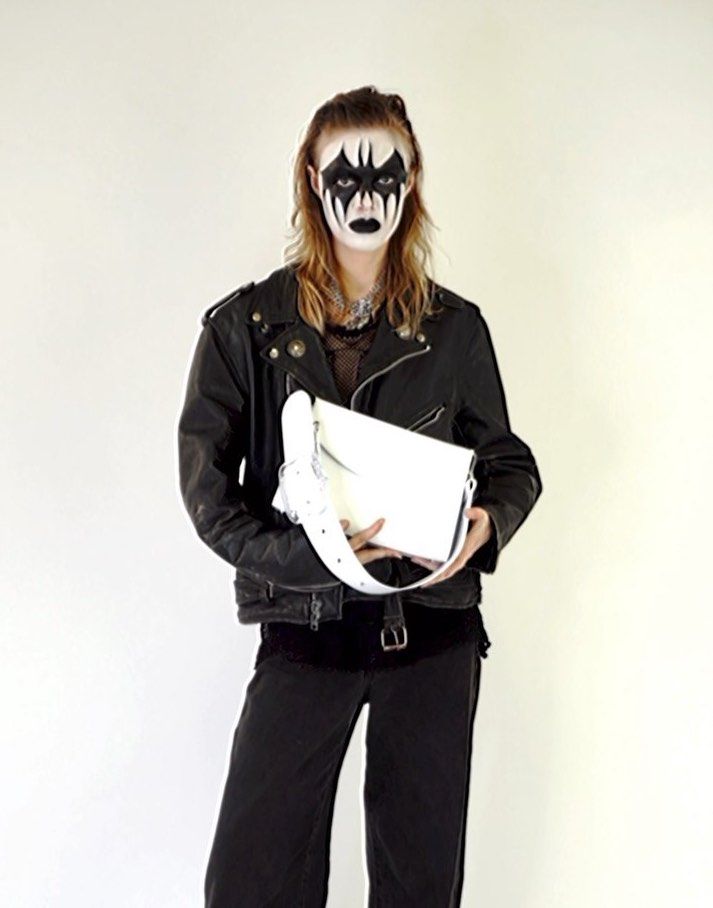

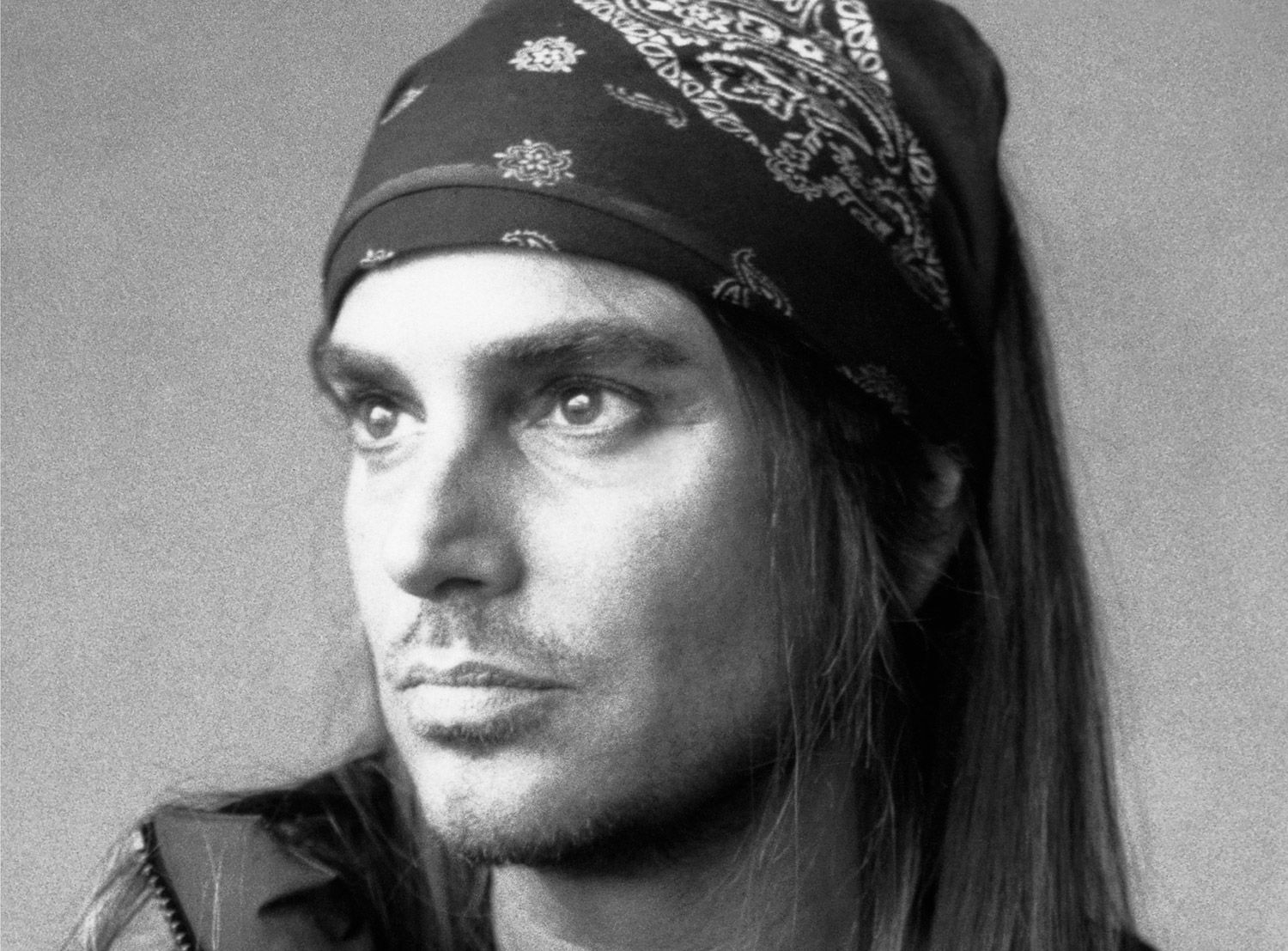

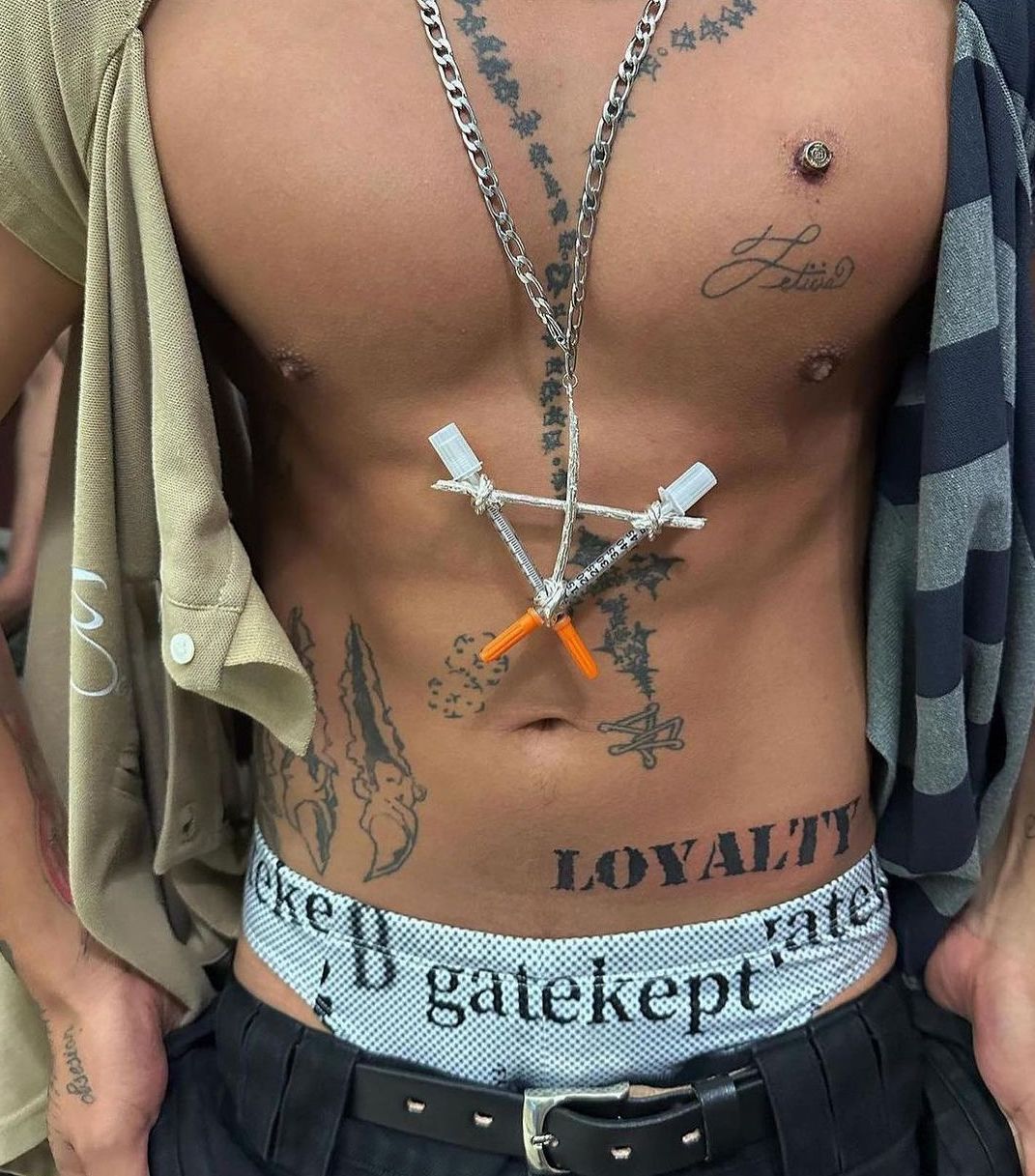

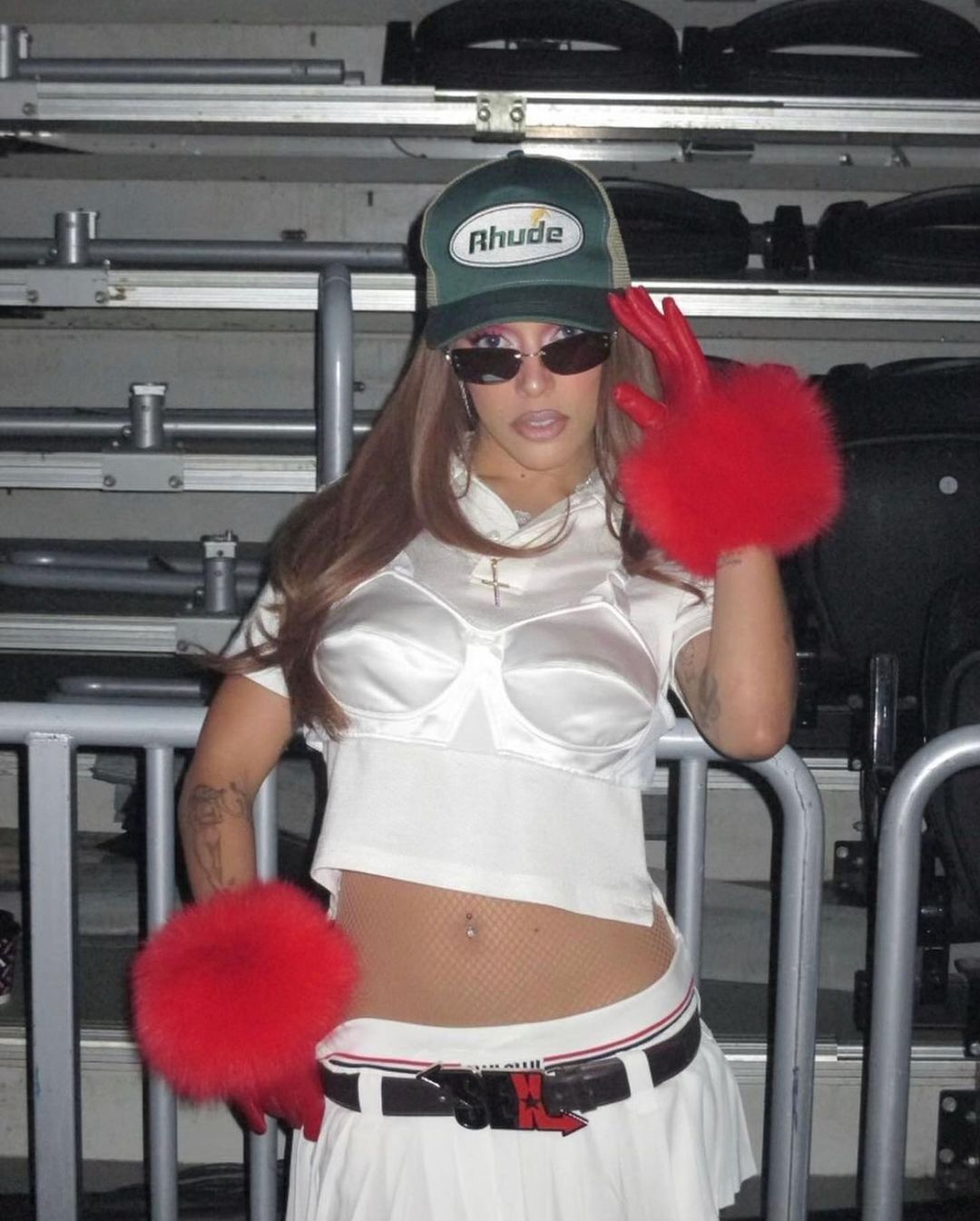

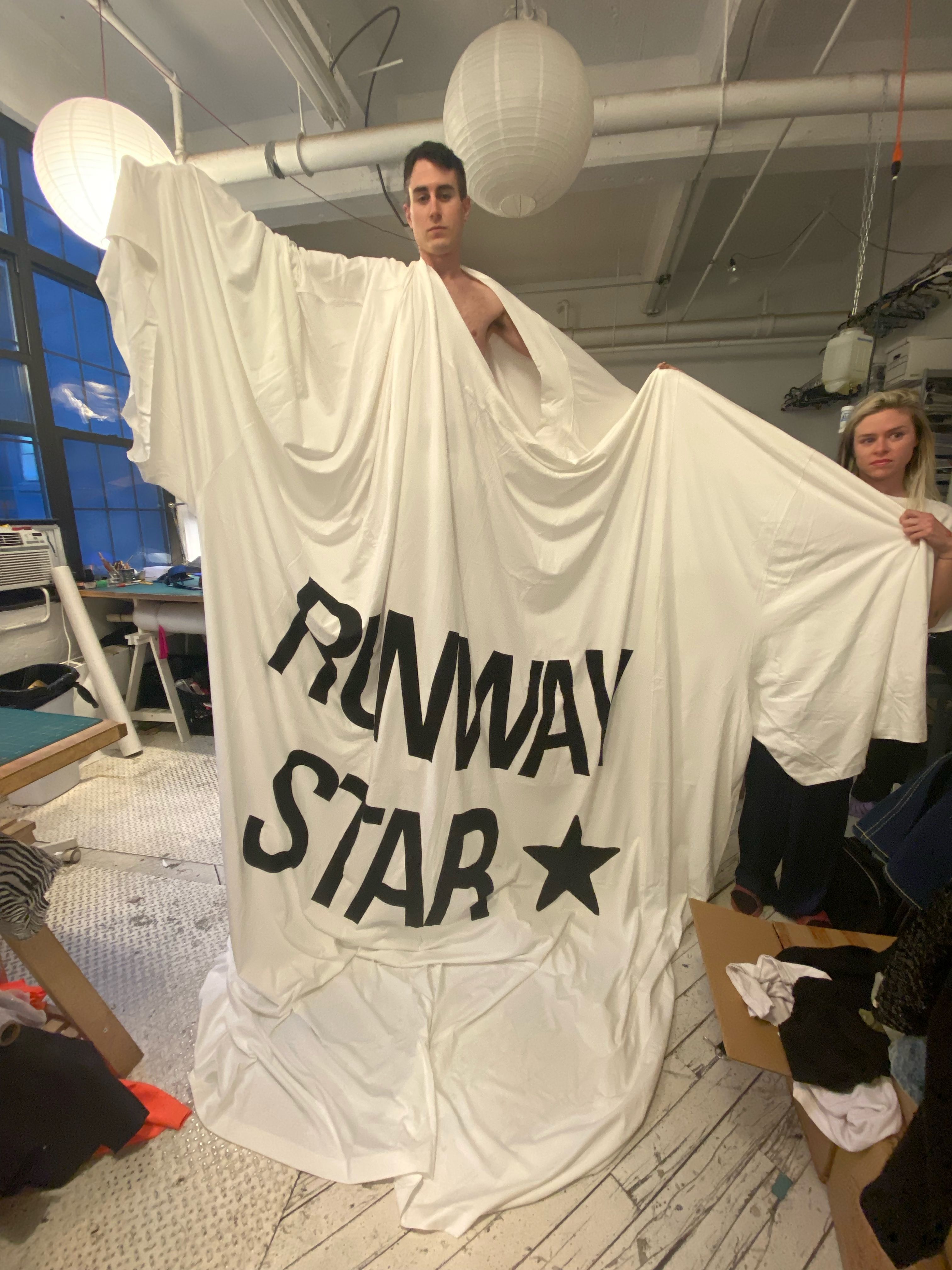

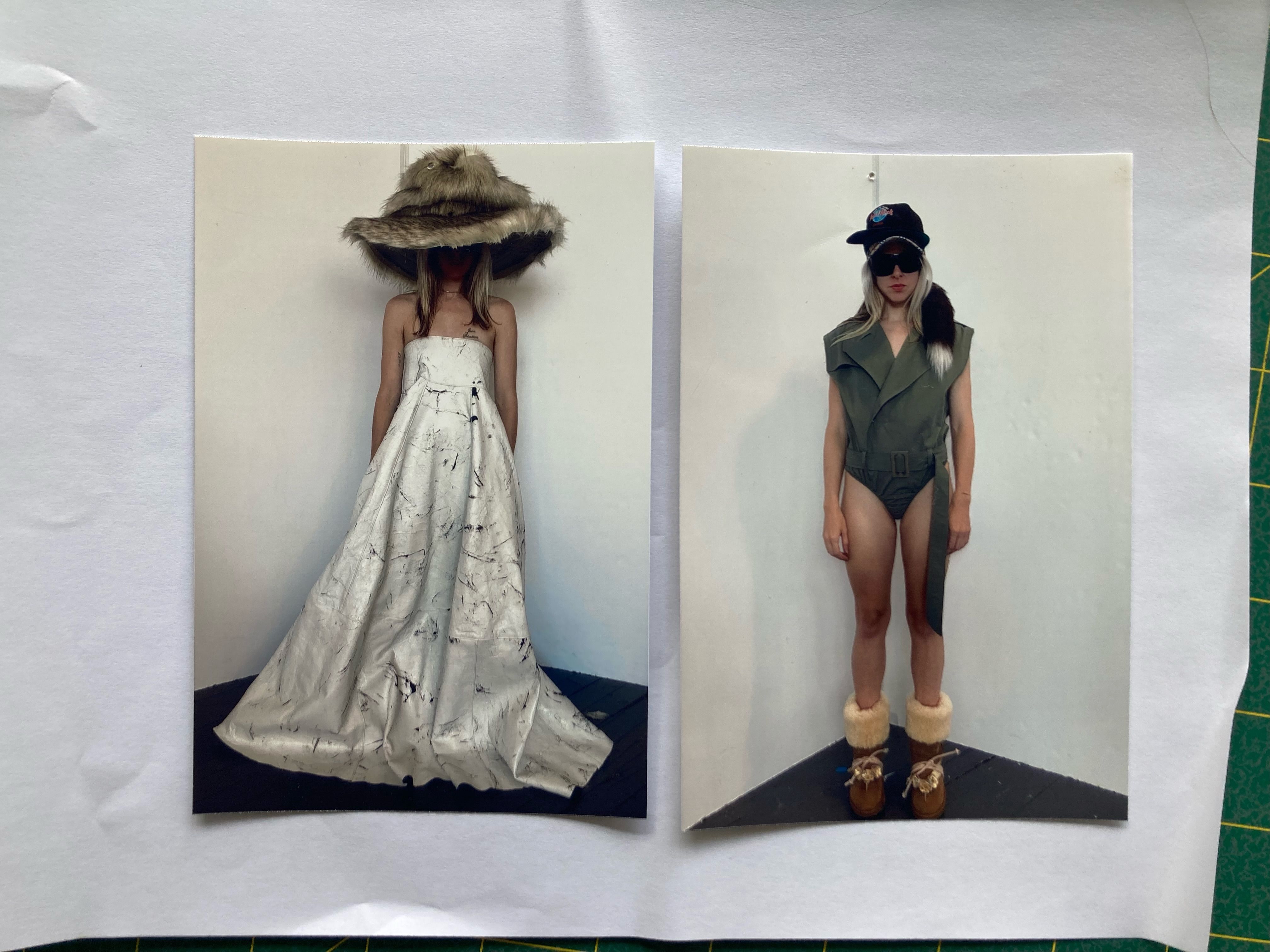

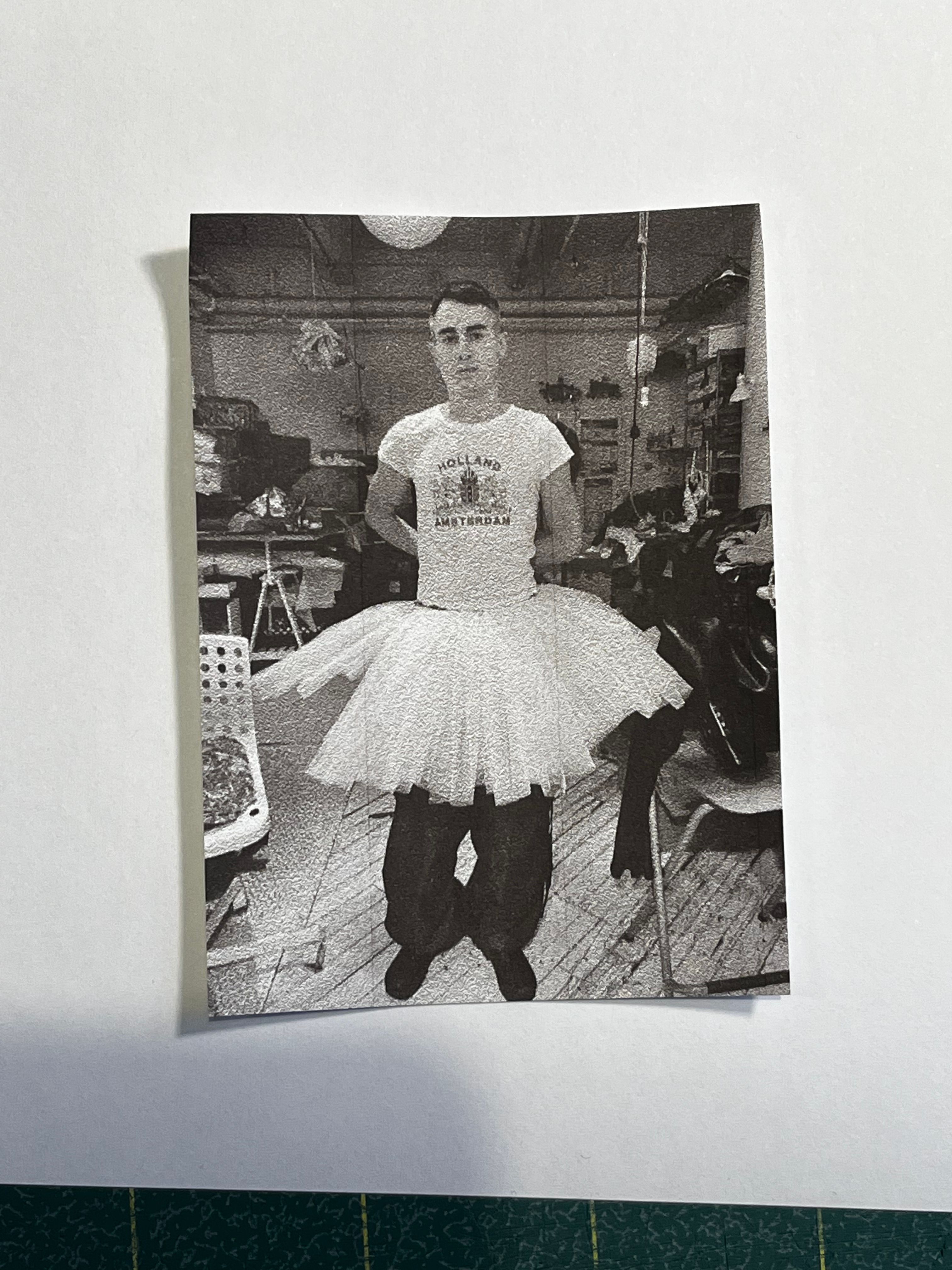

So, “Who the fuck is Vaquera?” For a brand based on the referential, the answer can be difficult to discern. Maybe it’s just the slogan on someone’s shirt—and indeed the brand released such a product for SS-18. Alongside exclusive, unreleased BTS taken from DiCaprio and Taubensee’s iPhones, I spoke to the designer duo about such an answer, their adamant Americanness, theorizing what “pure” fashion means, and being punk like Avril Lavigne.

AGNES MAGGIE SHU: Vaquera started on Tumblr, which speaks to the unconventionality both in your practice and route into fashion. Does Tumblr still inform your practice today?

PATRIC DICAPRIO: I’m from Alabama, Bryn is from Indiana. I think sites such as Tumblr, Instagram, Blogspot, and other social media platforms erased that distance from fashion capitals. Where I was, fashion was just Coco Chanel—a very cliché iteration. Basic. Tumblr allowed me to discover something that I didn’t even know existed, which is pretty powerful. I think about it all the time: if I hadn’t been on Tumblr, what would I be doing? Would I still be in Georgia? I guess Truman Capote made it to New York eventually. By helping me to solidify my interests, Tumblr fast tracked my success and movements.

AMS: Thinking about social media more generally, you’ve previously talked about social media being too easy of a medium to digest fashion.

BRYN TAUBENSEE: We missed the criticality that people had in the past. Social media enables that, where you can just see and flick by something, not actually make an educated opinion about it.

PDC: With social media, it’s either “like” or “don’t like.” If you don’t like it, it’s ignored, and if you like it, you literally just “like” it. People aren’t critical anymore. It’s more exciting when there’s a conversation around something. Martin Margiela quit designing because of this. The speed at which the images were being shown eliminates the thrill of the wait. Our show comes out before we even leave the venue. It’s sad not to be able to experience fashion in a physical way that is exciting and novel, where you don’t know what’s going to come out next, where it all feels cool and exciting. Exclusive, in a way. Now, a physical fashion show is available for everybody on Google. I know that exclusivity has this negativity to it, but I think that there used to be something that was exciting about how you had to be there to understand it. Now, it’s become so common to experience that, it’s become numb.

AMS: Bryn, you’ve previously spoken about the inevitability of selling out to survive and losing the DIY attitude that Vaquera is founded on. Is there a ceiling that shouldn’t be broken in terms of brand growth to stay away from the mainstream? How has your commercial growth influenced your design practice?

PDC: It becomes a problem when you give away part of your company, and are at the mercy of these people who have ownership over your work. We’re thankful to be working with Comme des Garçons and Dover Street Market because they are one of the only major fashion houses that remain independent. We use them as a model, and don’t ever want to limit our growth.

BT: We still do a lot of the patterning and sewing personally, which is why we have the shapes that we have. Since we didn’t study fashion properly, we have a kind of naive touch.

PDC: In the beginning, we were making it up as we went, choosing fabrics because they looked cool. Then it would be what we would make out of those. Which led to some interesting, but very uncommercial, and honestly strange collections.

BT: We were almost into choosing fabrics that were hard to wear or gross. We’ve always been into things that are gross because it’s funny to propose something that’s unrealistic or unappealing. Being commercial meant finding fabrics that are interesting but that we also want to wear. Early on, we wouldn’t even want to wear the clothes that we were making.

AMS: Since switching from the New York to Paris Fashion Week calendar in 2022, you’ve become more adamantly American than ever. Was this triggered by your imminent move to Paris? Or perhaps with finding a sense of stability within your collections, given the tumultuous state of America?

PDC: It’s both. You definitely feel more American when you’re surrounded by people who aren’t American and when you’re presenting a very American-looking collection to a French audience. Going back to what we were talking about, with access to Tumblr and social media, places aren’t so insulated, but rather it’s an [American] attitude that you can bring anywhere.

Part of the reason why we want to move to France is because we feel so unstable in New York with the political climate and inflation. We’re unable to even exist in a way that feels comfortable, and on top of that, we’re expected to think about the way luxury shoppers live and work, yet we can’t even relate to them while shopping at Trader Joe’s.

BT: I feel like we’ve never really fit in, so we’re always watching and using our collections to reflect our observations and thoughts as Americans. Even when we move to Paris, I think that we’re going to still be very American. I think we always will be.

AMS: You often position your work relative not just to the fashion moment but the current political state, such as the colossal American flag train back for AW-17, which was quite apt coming on the tails of Trump’s inauguration. You even prophesied the cultural narrative in AW-19, where you were looking into people’s homes, which was a rather apocalyptic vision of the COVID-19 years. How often does the sociopolitical context come into your practice?

BT: It’s always in our practice. We never want to make an overt statement like “America sucks” or “Trump sucks,” that can be a bit tacky. But we’re obviously thinking about those things. We want to present it, have people notice and wonder why we’re doing that. With the American flag dress, it was a really long train, so in that way it can feel like a homage to America. Yet, you technically can’t drop the American flag on the ground, and if you do, you have to burn it. So, there is no black and white. I think we’d like to present all of these thoughts within our work and allow our audience to draw their own conclusions.

PDC: I think we can access a certain truth, and even predict things, because we are so light-hearted about it. If you set out to do a very political collection, I think there’ll be less truth to it, because it feels so put on. I want to be a mirror. Let me take in what’s happening, allow myself to get out what I’m feeling, and in that way show the truth. When someone has a mission, they’re going to be biased and one-sided. That feels less real, less true, less diverse, and less likely to have a lasting statement. By having fun and being real about it, we are more truthful and impactful.

BT: I feel like you ultimately reach more people when you’re being a bit more neutral. No one wants a misrepresentation of something by being aggressive and overtly political.

AMS: Vaquera has been labeled as anti-fashion or even trolling the rest of the industry. With the consideration that fashion is founded in performance, I’d argue the opposite—that, by centering collections around caricatures of everyday personas, Vaquera is pro-fashion at heart by performing these tropes. Was performance ever your intention?

PDC: I feel like everything is performative. I think that is missing from fashion. This brand was built on that because we were like, “It’s so boring and depressing. What’s going on?” We moved to New York to have fun with fashion and feeling the fire when we got here. And we thought [the fashion scene] was so elitist, so boring, so commercial. The performative, exciting aspect of fashion is what’s missing, and what drives us to do what we do.

BT: I think there is no such thing as pure fashion. Even the negative parts of the fashion industry that we’re rebelling against, like commercialism, they’re part of fashion too, so technically that’s also a pure form of fashion. You need to have the negatives to react against.

PDC: It’s letting go of that idea [of pure fashion]. Letting go of that ownership or need to define something. Letting go of that need for authenticity, or the need for a pure form of anything, is really liberating. That’s what makes our work exciting. Aspiration to do the impossible. Even in the beginning, being broke and starting a fashion label, it was all about the pain and the hustle. Working towards something that seems impossible is how you make exciting work, and that inspires us.

AMS: What serves as a reference point for you now?

BT: I’m most impressed by people on the street who are kind of naive in their look. Maybe they’re a bit older and don’t know what they’re doing. But they look amazing. That’s my favorite look. That does feel pure in that way when they have a clear sense of style, but not necessarily informed, either.

PDC: I saw this guy the other day, I have to show this photo to you. An old man was walking across the street and he had a t-shirt on a hanger hanging off his collar. So fab. So cool. So avant-garde. Like, “I need to carry this shirt. I also have to carry my cane. So I’m just going to hang it on my shirt.” A pure form of fashion, maybe, is something that looks cool, but really is born out of necessity. This attitude of “whatever.” That’s punk. Someone who dresses a full look from Prada is not punk. Thinking of Avril Lavigne, with that video where she says, I’m not punk, I’m just a rock chick. Do I sound like her? Because she did have a point. I’m not punk, I’m just a girl who likes to rock out. Don’t call me punk.

AMS: For emerging designers, you’ve graduated from being the one making references to being the reference itself. What would be a Vaquera reference?

PDC: It’s looking at a mirror and seeing all these different reflections. That’s a rather mushroomy metaphor. It’s very full circle, because Vaquera is about the reference. In the early days, we were obsessed with recreating looks from Karl Lagerfeld’s Chanel exactly as they were and just changing the logo to Vaquera—it was very explicit. Now that we have found our own voice, we don’t rely on that as much. But something that is very Vaquera is the reference itself. If someone wants to reference us, then referencing other designers is what they could do. It’s meta.

BT: Everything right now has become about the reference, recreating things from the past and putting them back together. It is disappointing in a lot of ways, because it’s outside of the context that it existed in originally. It’s more interesting to reference while bringing it to current relevance, rather than doing it literally. I think that’s what we’re about, referencing the past and building off what has since happened, in a way that feels relevant to now.

PDC: Steal from the best, make it your own, that’s what they say is the recipe for success. And it’s real.

Credits

- Text: AGNES MAGGIE SHU