Hajime Sorayama: What I Draw Are Human Beings

|CASSIDY GEORGE

We have long depended on artists to help us visualize utopian futures and find beauty in what frightens us the most. Hajime Sorayama has understood the world of tech as primarily one of fantasy, and the world of art as one of entertainment. Cassidy George speaks to the erotic artist about objectifying women, his private obsessions, and intimacy with AI.

It’s the first thing you see when you wake up in the morning, and the last thing you think about before you go to bed at night. It’s beside you when you sleep, often suspended in your back pocket and most at home when held tenderly in your hands. It’s the window to your connection with others, the gateway to your memories, and the mirror through which you see yourself. Without it, you feel lost and alone––almost incomplete.

Half a century ago, the average smartphone user’s connection with their device would be completely unthinkable; this degree of intimacy between man and machine was once the stuff of dystopian nightmares. While we have come to accept our cyborg-levels of attachment to our phones as merely par for the course, fear still clouds the public discourse concerning the future of the next technological frontier: AI. Mainstream headlines about growing attachments to AI chatbots and girlfriends drip with judgement and position those already embracing the possibilities of new tech as outrageous or unwell. Meanwhile, many of the people stoking or searing in the flames of panic spend their free time on dating apps, keep vibrators in their bedside drawers, and wouldn’t dare leave the house without an Apple product.

We have long depended on artists to help us visualize utopian futures and find beauty in what frightens us the most. As the virtual realm eventually supersedes the real and our connections become less and less human, creative minds will be paramount in helping us see the light in a new dawn. Hajime Sorayama has long understood the world of tech as primarily one of fantasy, and the world of art as one of entertainment. As one of the greatest living erotic artists of our time, Sorayama—who is best known for his “sexy robots” (to put it bluntly)—has spent the past five decades celebrating post-human aesthetics and emboldening our lust for the inorganic.

Born in 1947, Sorayama came of age in post-WWII Japan, and traces his metal fetish back to childhood years spent admiring machinery in his industrial hometown. By high school, the self-taught illustrator shifted his focus toward a new “mania:” pin-ups. Despite his natural gift for drawing, Sorayama had plenty of other career ambitions—such as becoming a pilot, a sword smith or a temple carpenter—before enrolling in university to study Greek and English literature. He was forced to forfeit his academic pursuits after creating and circulating an erotic magazine on campus called Pink Journal. The publication, which lampooned his professors, resulted in his expulsion—and kickstarted his career as a freelance illustrator.

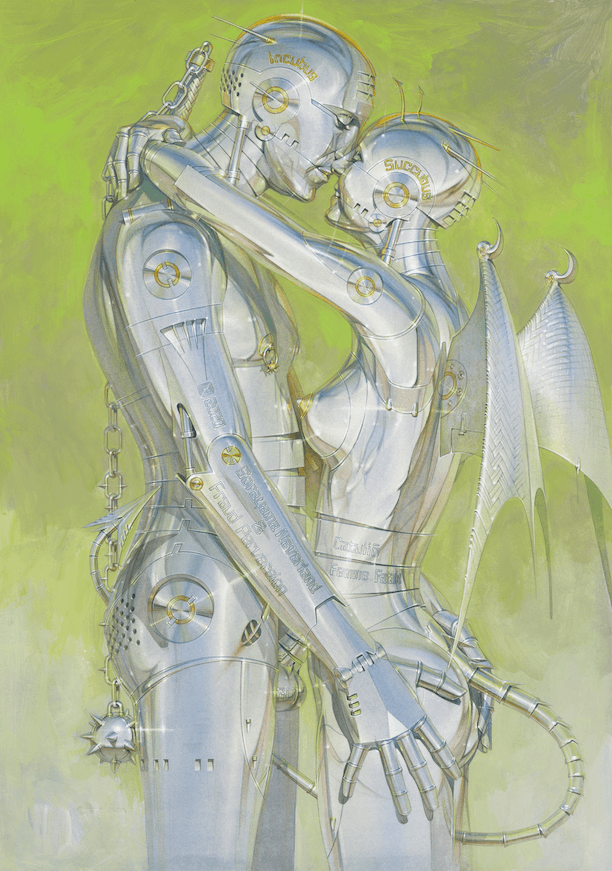

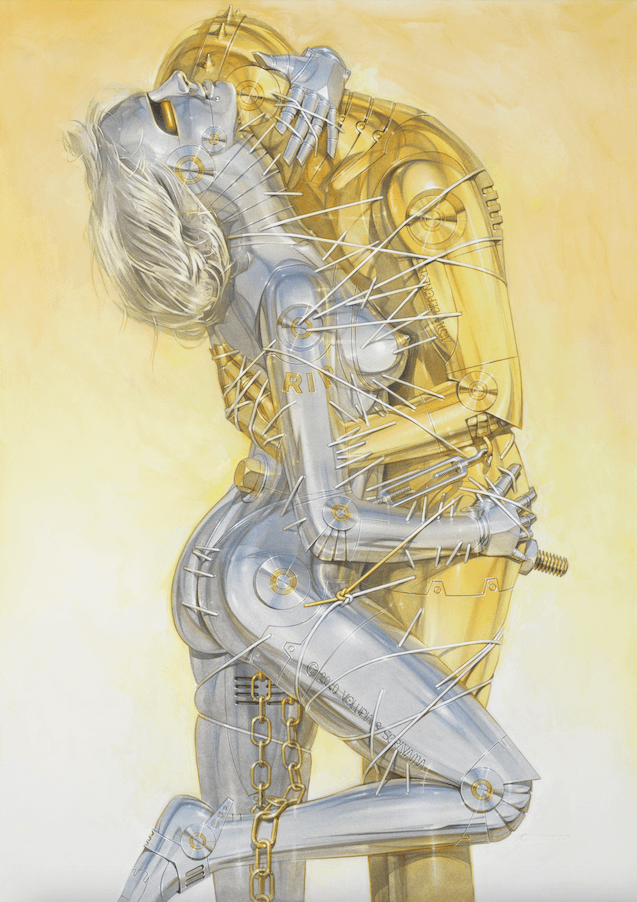

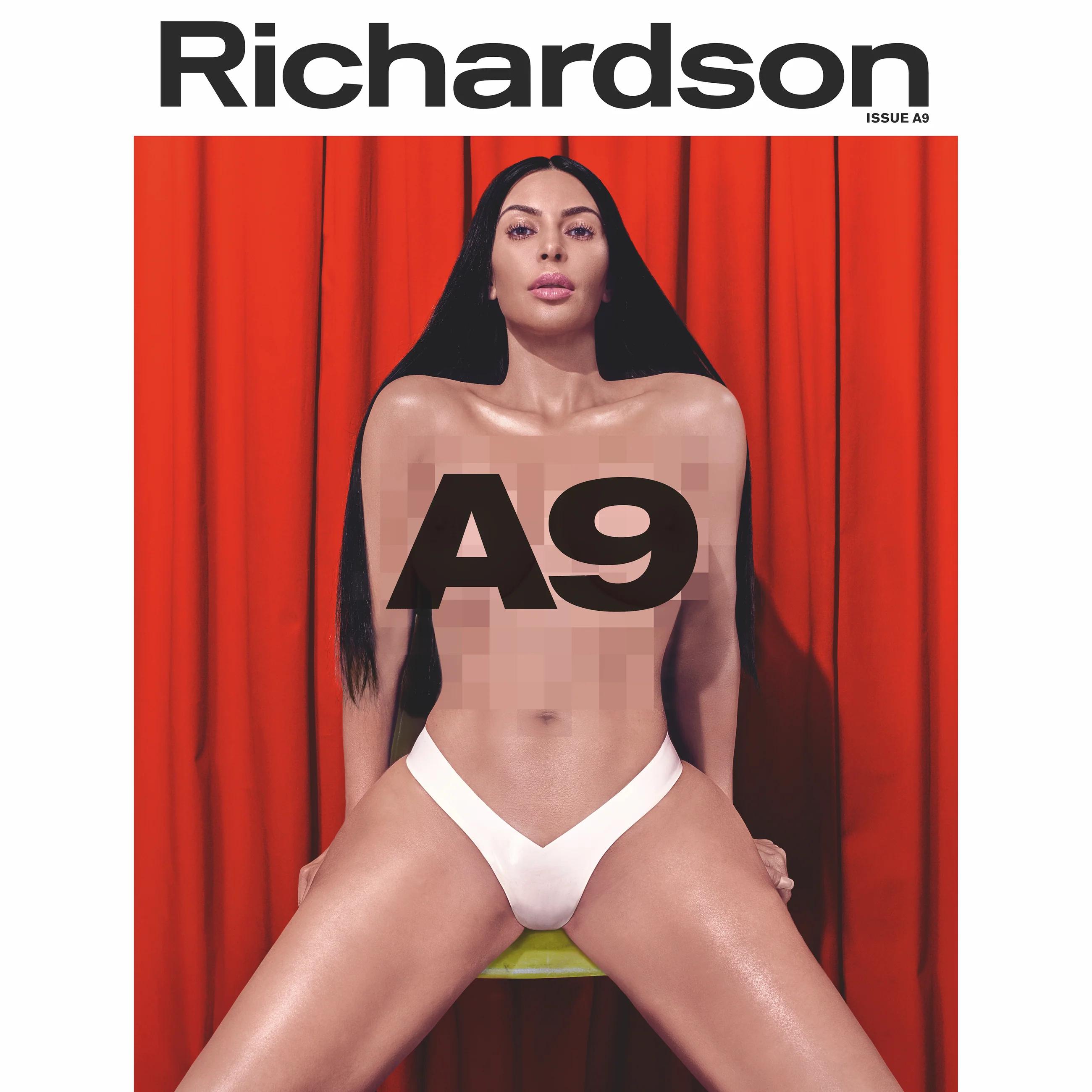

Sorayama’s love of ancient Greece has long loomed over his storied career, which is in many ways a contemporary retelling of the myth of Pygmalion: a sculptor who, in attempting to remedy the flaws of mortal women, creates a statue so perfect that he falls in love with it. In 1983, Sorayama fused his various fixations into singular artistic entities––pin-ups with metal flesh known as “gynoids.” In an almost Warholian fashion, Sorayama’s horny brand of futurism has become the stuff of legend. His iconography has transgressed the confines of the art world and reverberated throughout the realms of fashion, film and music, earning him a laundry list of esteemed collaborators such as Thierry Mugler, George Lucas, Dior, Aerosmith, Stella McCartney, Marvel, Richardson, and 032c summer cover star, The Weeknd.

Though his visions are high-tech, it doesn't take a rocket scientist to decode the timelessness and breadth of his work’s appeal or the immediacy of its impact. One of the most refreshing aspects of Sorayama's work—beyond its optimism—is its simplicity. In industries where depth and nuance are fetishized, Sorayama’s shameless obsession with things like beautiful women, weapons, robots and wild animals is delightfully straightforward. His infatuation with this subject matter will never expire, and neither, it seems, will the public’s attraction to them.

In recent interviews, he’s dropped zingers like: “hard work is proof of incompetence,” and “to be quite honest, it's porn,” when asked to categorize his work. On the occasion of the artist’s first solo museum exhibition, Desire Machines, at the MoSex in Miami, 032c asked Sorayama a few burning questions.

CASSIDY GEORGE: Firstly, tell me a little bit about the show at the Museum of Sex––how is it different than previous exhibitions? Your hardcore works are on display for the first time, correct?

HAJIME SOROYAMA: There are many works that other museums and galleries would not allow me to exhibit because they are considered obscene. The Museum of Sex has only allowed me to show my hardcore works within their rules. While I am happy that they have been given the opportunity to be put on view, I want to flag that there is surveillance around the pieces and viewers' interactions with them.

CG: How drastically have societal attitudes toward sex—both in the field of art and in the public arena—changed over the span of your career?

HS: Nothing has changed in me personally. Sex based on the instinct of survival is natural and beneficial, as is having an intellectual curiosity about sex. If we deny ourselves this, humans will simply perish. People just misjudge themselves, thinking that they have become smarter by a distorted society. Who benefits from banning talking about or expressing sex? I don’t understand it at all. A distorted society is one that calls it “pornography” and brainwashes us into thinking it’s bad. I hope that the day will come when women, men, and everyone can proudly say that they like what they like.

CG: Your father was a carpenter—did he instill a love of craft in you? Was your attraction to metal in some ways a kind of rebellion?

HS: It has nothing to do with rebelling or resisting my father. I was born and raised in a small town and in an era with little entertainment, so I became obsessed with metal before I truly knew it. My first experience of ecstasy was on my way home from school as a child, watching the way metal absorbs and reflects light as it was being processed at the factory.

CG: I think one of the most overlooked public arenas for erotica is advertising. You used to work in this industry, can you tell me a little bit about that chapter of your life? How did it inform what you do, how you work, and how you reach your audiences?

HS: When I started my illustration career in the 1970s, pin-ups were mainly used for advertisements for luxury goods such as alcohol, cars, and cigarettes. I was working my ass off drawing what clients asked me to do. Luckily, I drew women more beautifully and skillfully than anyone else, therefore I became famous for drawings in that genre, but I actually have drawn hundreds of drawings that are not pin- ups. In the world of hyper-realistic illustrations, there was no context, and we were living in an age where skill was the key to success, so I revealed my techniques as I was pretty confident that none could copy my skill.

CG: Your work explores fantasies of intimacy with AI––

HS: Honestly, I am not really interested in AI. AI can perform calculations and analysis but it’s impossible for AI to perform the function of the human mind wherein humans find each other desirable.

CG: You mentioned in a previous interview: “I am not drawing robots.” Does that mean that the vast majority of people who look at your work are misunderstanding it?

HS: What I draw are human beings. It’s the fantasy about humans having metal skin and being able to design themselves however they want. That’s why the figures in my drawings have sex, drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes, and sexually stimulate.

CG: Your work has existed in many mediums and has various points of entry for the viewer, be it in a fashion collaboration, an album cover, a sculpture, or a large-scale painting. Does it carry the same weight, hold the same meaning, and offer the same messaging, regardless of its form?

HS: I have never called my work art. My work is entertainment. I am aspiring to be an entertainer in the vein of a magician. I have long been insisting that people who view my work should enjoy it as they like. For me, a fashion collaboration is a job. As long as we create something of good quality, I am happy.

CG: How have you responded to criticisms that your work objectifies women?

HS: I believe that fans of my work—especially women—understand that the women I draw are not “objects” but real humans with strong willpower. People who think they are objects probably only see it from that singular perspective, but I don’t object to such criticism. I am OK with whether people like it or dislike it.

CG: Who are some of your favorite erotic artists from the past? Which have had the biggest impact on you and why?

HS: I think Katsushika Hokusai is as genius as me. I won’t explain why, so if you don’t know Hokusai—please Google it.

CG: Do you have any other private obsessions or things that deeply fascinate you that maybe don’t appear in your work?

HS: I am the happiest person when I lock myself into my studio drawing all day long. But in order to keep my social skills, I go home to have dinner with my wife and go on cruises with friends. I am interested in anything that will help my work, but I rarely get excited about anything.

Credits

- Text: CASSIDY GEORGE

Related Products

Related Content

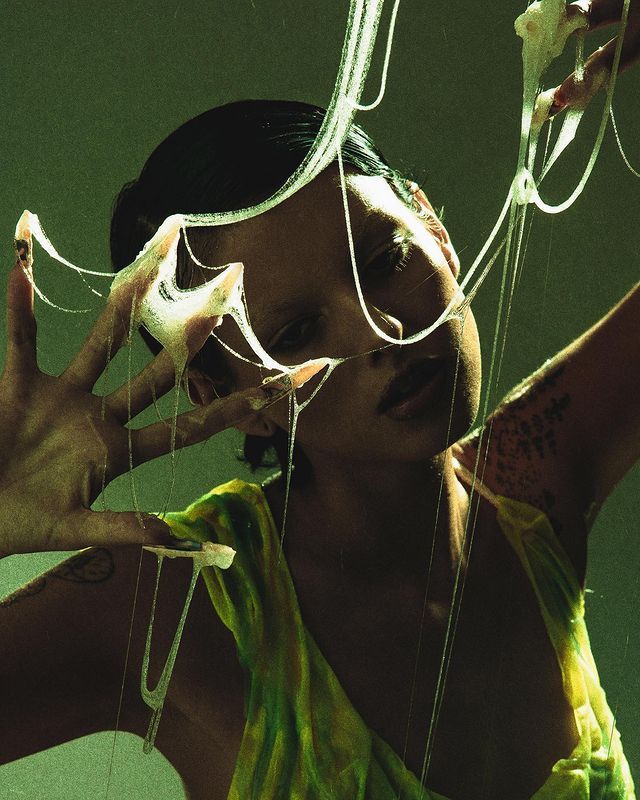

Notes From Underground: Slime Fetish

Notes From Underground: LUKE NUGENT’s AI Editorials Fictionalize Subcultures

Wong Ping’s Golden Shower

Shimmering, Twisted, Tangible: Meet the Sci Fi Cinematographer Behind Ex Machina

RICHARDSON Magazine Rethinks The Seedy

Drain Gang

HR GIGER & MIRE LEE: Horror, Slime, and Satanic Eroticism

From Sex-Tech to Global Warming: The Chronicle of 17 Artists Who Created BMW’s Acceleration Aesthetics

Girlhood Is Not A Moment: SHUSHU/TONG