Decolonize Your Trip

|Samuel Hyland

In today's media landscape, a book review is often a slap on the back. A handshake among colleagues that says, “well done.” But we have never been afraid to offer critique when critique is due. In our print section Berlin Reviews, we've always tried to take the propositions of a book seriously and push them to their extremes.

Archive Berlin Review from our issue #41.

R. Gordon and Valentina Wasson stumbled upon a batch of chanterelles on their honeymoon in the Catskills in 1927. Valentina, who had been fond of fungi in her childhood Russia, was overjoyed. Her US-born husband, who had not grown up in a mushroom-reverent house hold, was petrified. Intrigued by their own cultural differences, the Wassons went on to coproduce seminal research in ethnomycology. Unfortunately, and perhaps predictably, history really remembered only one of them. Valentina may have inspired her companion’s lifelong foray into fungus, but Gordon is the one who became the “face” of the modern (and magical) mushroom.

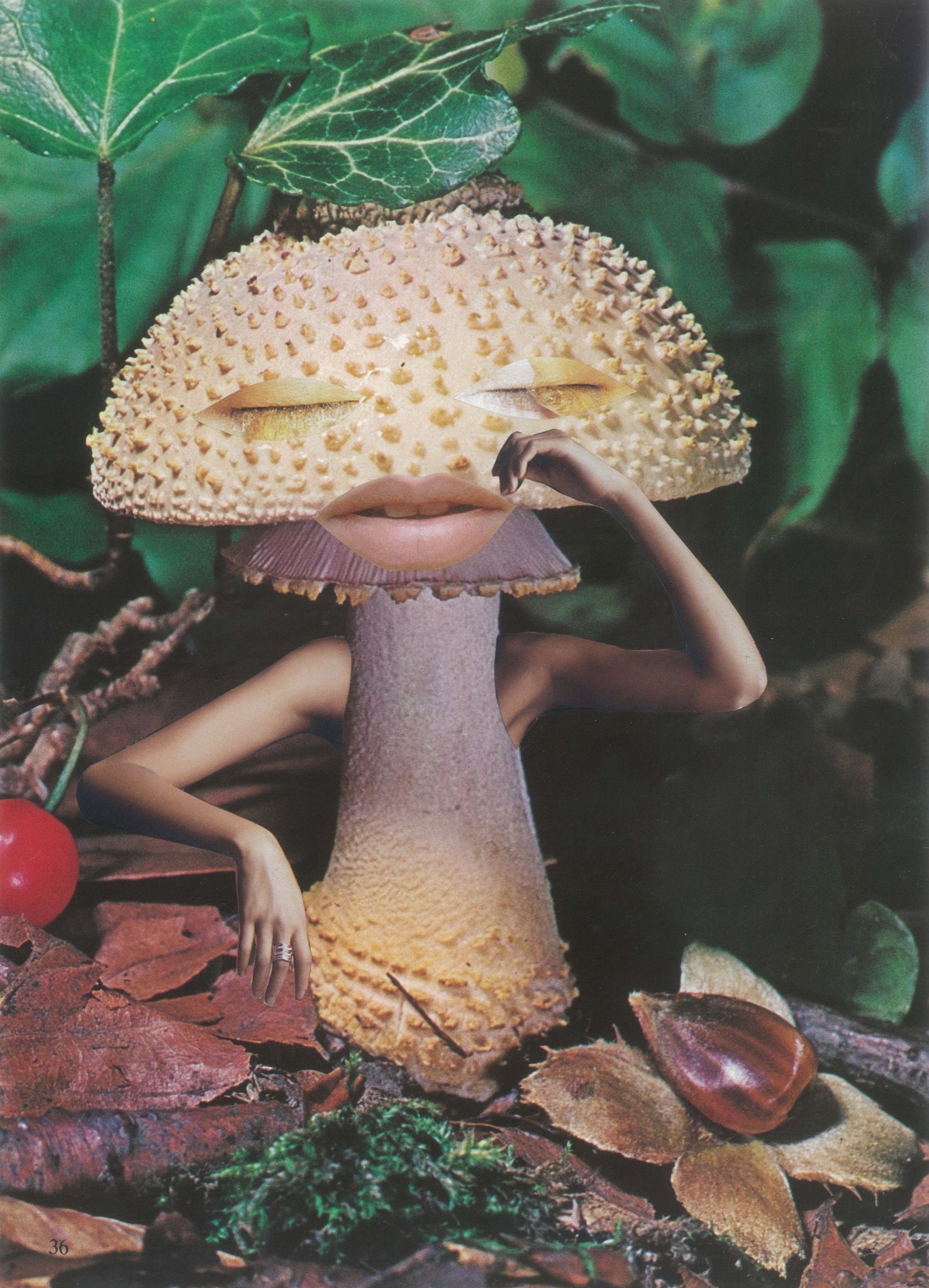

Published by Anthology Editions, Brian Blomerth’s Mycelium Wassonii represents an effort to spotlight the Valentinas of mycology — the discipline’s unsung pioneers. Blomerth, an illustrator known for his unique brand of tongue-in-cheek surrealism, tells the Wassons’ tale with visuals not far removed from those produced by actually being on ’shrooms. At little more than 100 pages long, the dense paperback is half comic book, half ancient book of spells, its unearthly spreads sandwiched between front and back covers scrawled with tripped-out script in unfamiliar languages.

We join the Wassons on their honeymoon, where Valentina’s pro-mushroom lobby is echoed in illustrations of vibrant fungi “speaking” in hieroglyphics. By the end of their trip (get it?), Gordon — reassured after Valentina eats but is not killed by her harvest — has developed an appetite for wild mushrooms, too. The two hone their newly shared obsession in the kitchen, a habit that, over the years, yields a publishable body of research — and a hybridized cookbook-slash-cultural-treatise that piques the interests of literary critics and the CIA alike. The latter agency funnels money into the Wassons’ project under the guise of something called the Geschickter Fund for Medical Research, which grants them the autonomy to pursue their study of nature’s hallucinogens — and the many rabbit holes such research entails. (True story: the government literally paid them to get high.)

The Wassons’ curiosity lands them among the Mazatec, an Indigenous people of Mexico known to use mushrooms for their psychic and healing powers. They endear themselves to Mazatec elders, who guide their visitors, on horseback, through physical terrain and supernatural territory in rituals, the Wassons marveling with reverent curiosity. More accurately viewed, it is only the Wassons who are endeared: at some point, one Mazatec elder is illustrated communicating in a whistle-based dialect with nearby trees. Per Blomerth’s transcription: [Tree] “What are you doing?” [Elder] “Baby sitting these eggheads for cash!”

This dynamic becomes an issue on their second visit, when a photographer accompanies Gordon. Wise woman María Sabina agrees to consult the fungi for the Wassons, with the caveat that they keep the experience to them-selves. “Showing the photos or telling anyone,” she says, “would be a betrayal.” The documentation, and the details, soon appear across American newsstands. As high-seeking beatniks overtake Mazatec lands, an elder sets them ablaze, determined to get rid of the colonizers. By the time nature is restored, María Sabina can no longer communicate with the mushrooms — but the beatniks can. Blomerth’s characters are rendered with the artist’s signature “dogface” anthropomorphism, traveling between universes, realms of being, and theorems with springy tongues hanging out of their wide-open mouths. It is Blomerth’s visual glimpse into a niche front of American colonialism, where supposedly well-intentioned cultural aficionados become complicit in the exploitation of Indigenous people and lands. The beatniks’ theft of María’s supernatural prowess points a hazy finger at every reader with a penchant for fungal psychedelia: our own highs are direct descendants of those first felt by the snazzily dressed hipster-colonists who appropriated them so many decades ago, and we are no less guilty than they. This lesson is especially relevant considering that the magic mushroom, complete with all its political associations, is “back.” The micro-dosing trend, wherein users take tiny doses of psychedelics to experience mental health benefits (without all the snakes and skulls), banks on the repetition of a much bleaker history: lay waste to a spiritual tradition — for which certain users were probably once punished — repackage it for luxury consumption, then cast it aside for another era to make sense of.

Still, we can pay homage to the mycological Valentinas, to the barrier-breakers, while condemning the lack of consciousness of their second- and third-degree followers. Perhaps things would even go differently if we let people with mushrooms in their cultural DNA lead. We might not be in this predicament, Mycelium Wassonii seems to imply, if we had done so in the first place.

Credits

- text: Samuel Hyland

Related Content

MICHAEL POLLAN Changes His Mind

Golden Teachers: Can Mushrooms Save the World?

BRING ON THE WATERWORKS! A History of Pissing in Art from 1280 to the Present

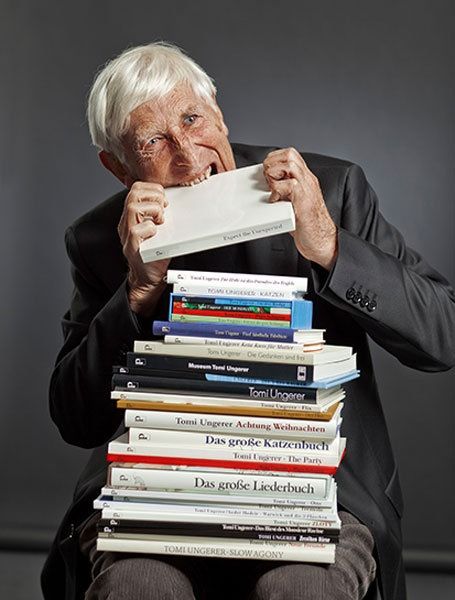

TOMI UNGERER (1931-2019): Waiting for Godot

“We trust our friends. And we trust ourselves.” ELVIA WILK on Berlin’s Cultural Class, Grief, and her Debut Novel

BENOÎT JEANNET’s index of the Earth explains why we love rocks

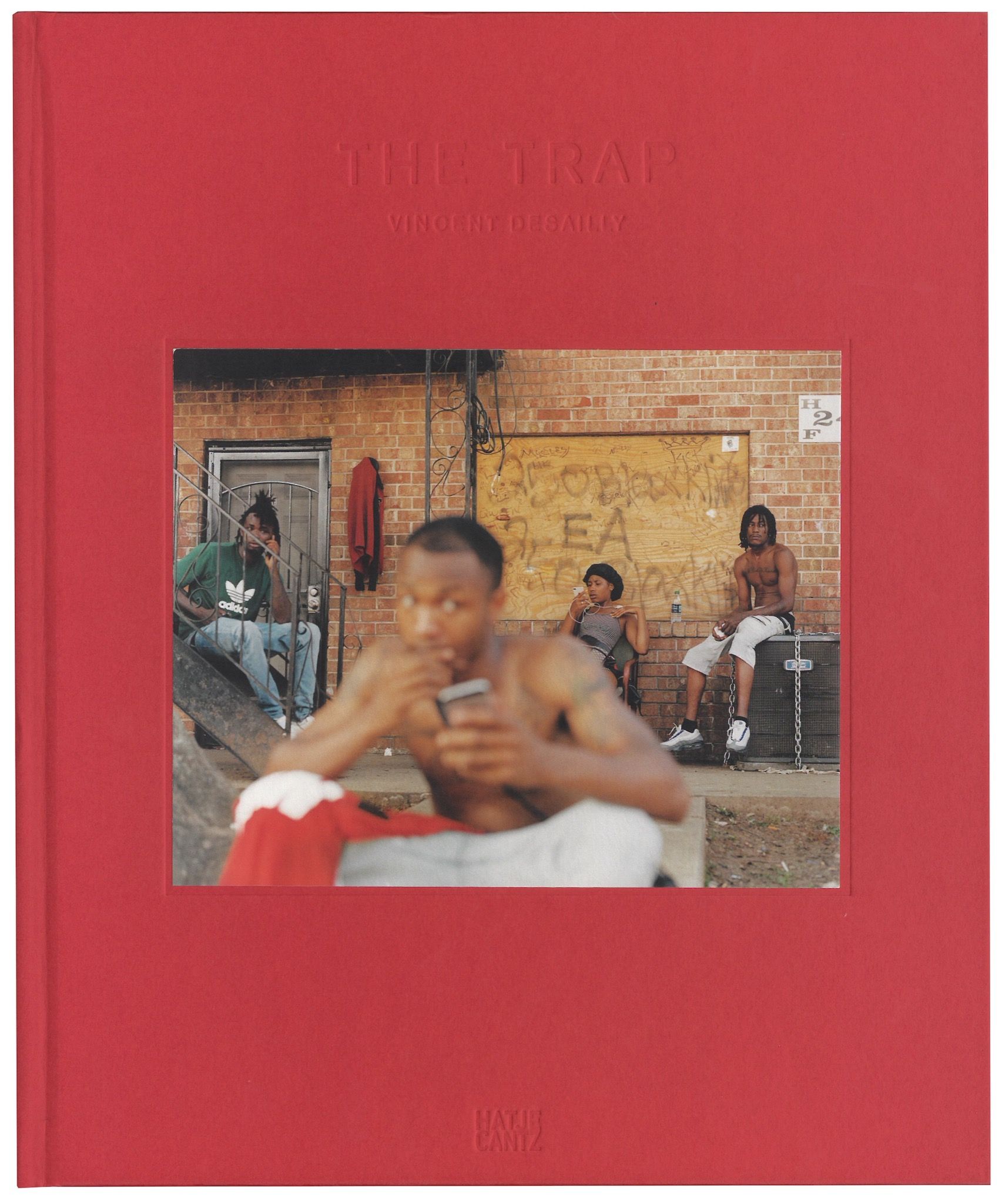

The Trap

Pre-Teen Modernists: THE PLAYGROUND PROJECT