An Orgy of the Mind With Charlie Fox

|SHANE ANDERSON

Having been described as a “general purveyor of the macabre” by Vogue, Charlie Fox is a self-designated feral animal, who never shies away from the darker and kinkier aspects of culture. The author of This Young Monster (2017), a book-long exploration of monsters and monstrous thinking, Fox is also a curator, who has recently put together the two-part group show “Flowers of Romance” at Lodovico Corsini in Brussels.

Torbjørn Rødland, Boy with Japanese Knife, chromogenic print on Kodak Endura paper, 2023. Courtesy of Lodovico Corsini

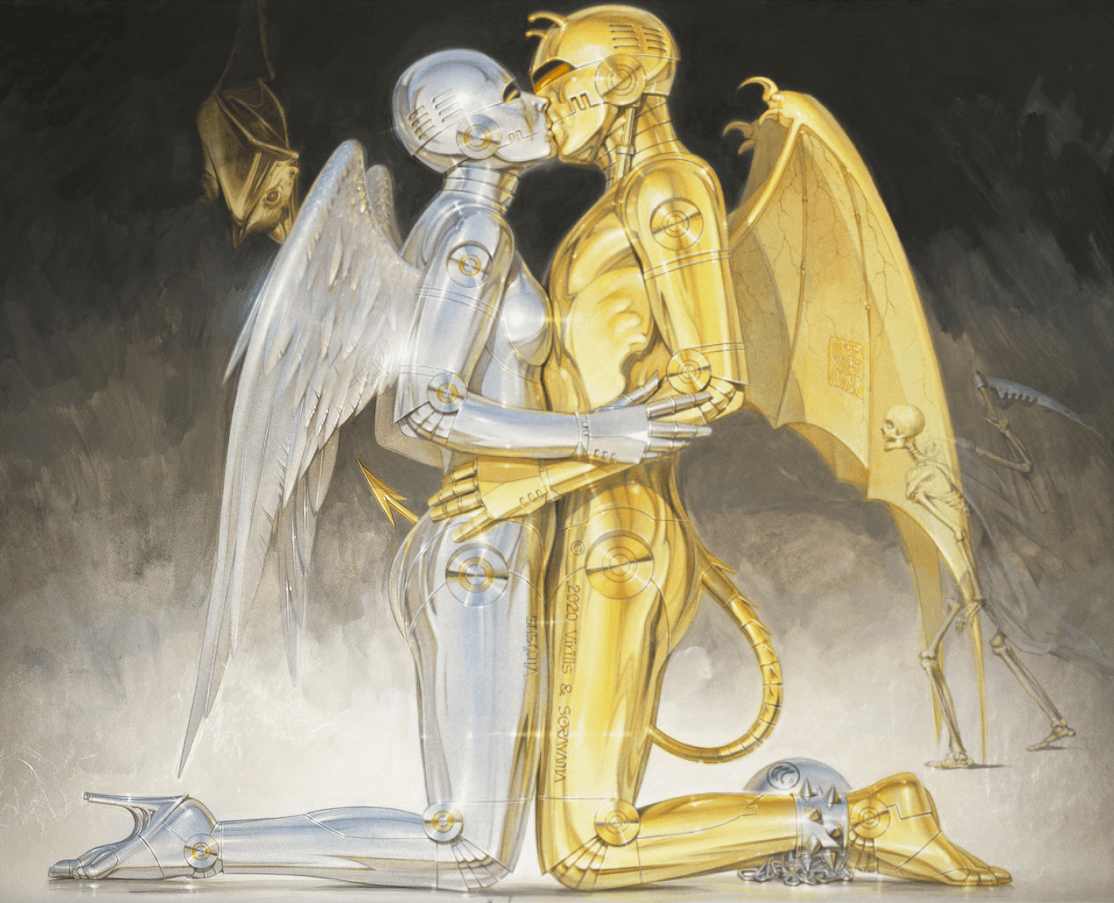

Act 1 “Day,” was a sweeter counterpart of the duet and featured works by Matthew Barney, Hajime Sorayama, Cy Twombly, and others, Act 2 “Night,” which is currently on view, is the more sinister twin and features different works by some of those artists alongside additions by Nan Goldin, and Ed Ruscha, amongst others. Prior to the opening of Act 2, Shane Anderson spoke to Fox about the orgy in his head.

SHANE ANDERSON: What’s the relation between your writing and curatorial practices?

CHARLIE FOX: It’s all the same thing, really. When I’m writing, I want a mixture of textures. I like making mutant entities. The same is true for the show. It’s all about a certain mood. Some kind of dreamy thing where the rules of reality are temporarily suspended and where normal logic melts.

SA: So, it’s all about collaging?

CF: One analogy is that it’s like a Still Life from the Old Masters, where they’d have tables with fruit, flowers, a silk glove, and other things. An exhibition is like a tableau or feast where you can have things from different planes coexisting. It’s a self-contained world. I don’t want to say world building because I think that’s something different but the attraction of art to me is creating a particular kind of world that couldn’t exist elsewhere and where things have a strange relationship. The experience of time is flattened and it’s all very psychedelic.

SA: How did the show come about?

CF: I was watching this Ozu film, Late Spring. There’s this bit where some married women are sitting on one side of the bench and some unmarried women on the other side in front of this tapestry of a faun and a nude figure. The married women are telling the unmarried women how awful their lives are, and the unmarried women are saying the same thing, but they’re both mocking one another. It’s a moment of social savagery in this very straitened society with erotic subject matter. Then I was lying in bed, thinking I should do a show about that. About spring and this vernal vibe but like walking around a Disney Garden of Eden while tripping. And then a few months later, I was on mushrooms in a park in London listening to My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless. The grass was alive and the treetops were mating and creating this stained-glass roof. It was so beautiful. It was like the Garden of Eden. That all fed into it.

Francesca Facciola, Two Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other Male (left) & Female (Right), “F is For Fun Part 2,” 2023. Courtesy of Lodovico Corsini.

SA: How did you go about selecting the pieces?

CF: You’re kind of inviting ghosts into the party and thinking, well, it would be good to have Matthew Barney and Twombly fuck, and it’d be good to have Dennis Rodman in a wedding dress. You could also say that Sade’s video for “No Ordinary Love” served as the source code. A lot of its imagery is the vibe I was going for. Heartbreak, longing, and desire are all themes.

We spent a lot of time trying to get Bear and Policeman (1988) by Jeff Koons, where the bear is showing the policeman the whistle, because to me that’s an illustration of Eve and the snake. That sculpture is from the Garden of Eden. But unfortunately, that piece would have been the budget of the entire show.

SA: And the title “Flowers of Romance” comes from a PiL album, right?

CF: Yeah. I love that album. It’s got these weird percussive bits, where it’s like someone’s going insane inside The Jungle Book. Sam [McKinniss] told me that it’s a terrible title. He said, it’d be like calling something “meals of food.” [Laughs] But I like how generic the title is. It’s almost like a pharmaceutical company. There’s something so flat about “Flowers of Romance” that you can refract everything off it.

Frans Snyders, A still life with dead game and a basket of grapes set on a red table cloth, oil on panel, ca 1614

SA: The show is divided into two parts. The first one is sort of sickly sweet—

CF: You’re right. Some of the imagery that I started to collect around the show was photographs of sweets. And, you know, when you look at photographs of Skittles, it hurts your teeth. But it’s also very erotic. And so, the second part is different but it’s not a straightforward light and dark contrast. The second part is more nocturnal, it’s more…decadent—and if it were up to me, it would always be night.

The point is, there used to be a time when you could do a show with naked bodies or something and that would be meaningful but today that’s totally played out. I was more interested in doing something where these things are sublimated, where even a dog’s teeth become erotic. There are loads of examples, like in Matthew Barney’s work where a car is substituting a body and a hole in the ground is a sexual orifice. That’s the logic of the show.

Installation view of Lodovico Corsini, “Flowers of Romance, Act 1 (Day),” Galerie Lodovico Corsini, Brussels, 2024

SA: So, if the different shows are not opposites, what are they?

CF: They’re a power couple. They have some things in common but there are dissonances. The first part is called “The Day of Smitten Leopards” and the second one is “The Night of the Heartbroken Raccoon.” It’s not like one is happy and the other is sad. There’s a continuity but it’s more like a Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers kind of continuity.

SA: One thing I’ve noticed about when you talk is that you have this sense of nodes and about what connects to what. Would you say this of yourself?

CF: That’s just how my mind works. It’s very natural for me to have a lot of stuff mixed together. It’s like a weird orgy inside my head. To take an example, let’s think about the guitar sounds in “Maggot Brain” by Funkadelic. And then think about the performance art being made at the time, which was about stretching or deforming the body. And I can hear [that track] in work like that. Then, I empathize with the material and think about what other material it would like to be near. And so, I think it’s quite obvious that Matthew Barney’s work would fancy that. It’s like two wolves whistling at each other. Everything is flirting with each other.

Certain people find this way of thinking very weird. Like with [This Little Monster], people asked: why do you put all these things together? There have been other coherent books about David Cronenberg, “Hammer horror,” vampires, and stuff, which is great, but I’m all about things mutating. It’s all about watching material distort or transform and seeing what you can do with it. It’s more monstrous that way.

Matt Copson, Baby, Bronze, UV reactive pigment, UV bulb, 2024. Courtesy of Lodovico Corsini

SA: Would you say then that you’ve adopted monstrous thinking?

CF: Yeah. And the whole formal structure of [This Young Monster] is that it transforms. It begins as a history of the idea of the monster and a conventional essay but then the form begins to stretch. I want it to riot. I want everything to be anarchic. The same goes for the book coinciding with the shows, where we didn’t feature any essays. I’m not interested in doing a monograph on the “de-terretorialization of the uncanny.” All of that imagery is trying to create the mood of the show and that’s much more interesting to me than elucidating some sort of aesthetic position. It’s more dreamy. There’s a kind of weird chaos, a semiotic debauchery of all things together. And that’s at the heart of everything I do.

SA: One thing I noticed is that the book to the show is very 90s.

CF: I guess the conventional read would be that it’s nostalgic. Everybody has this anxiety about the 90s, imagining it as the last innocent time before the internet or cell phones, but that’s just Instagram shit. Before the internet there was TV. Everybody was just stopping to look at the TV. Nowadays, people think the only relationship you can have to the past is nostalgic. But my relationship with a lot of those things is haunted. That’s something we don’t want to talk about. We don’t want to talk about the terror of the past, we just want to imagine it as some kind of utopia. That isn’t there in the past though.

All the images in the book are things I am attached to. There’s the footballer Roy Keane, Sinead O’Connor in Butcher Boy by Neil Jordan, Hunter Schaefer in Euphoria, and a lot of my childhood dog who’s dead. There’s a lot of strangeness to it all and the texture is important. Think about Frasier. What is Frasier? It’s this beautifully designed sitcom about two brothers but they’re really a gay couple. It was a way of sneaking a gay sensibility into mainstream TV. There’s that one image in the book where he’s doing a blind wine tasting but it could just as well be a fetish dungeon. There’s an internal perversity or sadness to the images a lot of the time.

I gave a copy of the book from my haunted house show at Sadie Coles to John Waters, and he said, “This is great. It’s like performing brain surgery on you.”

Promotional invitation for Lodovico Corsini, “Flowers of Romance, Act 2 (Night),” curated by Charlie Fox. Galerie Lodovico Corsini, Brussels, 2024

SA: Are you writing nowadays?

CF: Yeah. Everything begins with the writing for me, and I just finished a book. There have been all of these supernatural folktale-but-now fiction books about a woman giving birth to an owl or whatever in the last few years, but the prose has always been so numb for such an insane thing. And I thought, wouldn’t it be more amazing to imagine your sensuality going into overdrive because you’ve been infected with this creature? Wouldn’t it be amazing if you could smell everything? If you could eat roadkill and it tasted delicious? There needs to be room to celebrate that. Rather than stories where the character is just lying in bed unable to recognize their feet and it unnerves them. That kind of magic realism is dead. I thought, fuck that, I’m not having it. I mean, a lot of my work is stimulated by being so bored. It’s like, but we could do this and why don’t we?

Installation view of Lodovico Corsini, “Flowers of Romance, Act 2 (Night),” Galerie Lodovico Corsini, Brussels, 2024

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON

Related Content

Hajime Sorayama: What I Draw Are Human Beings

Welcome To Hell: Ben Ware On Extinction

Lankum's Antidote To Alienation

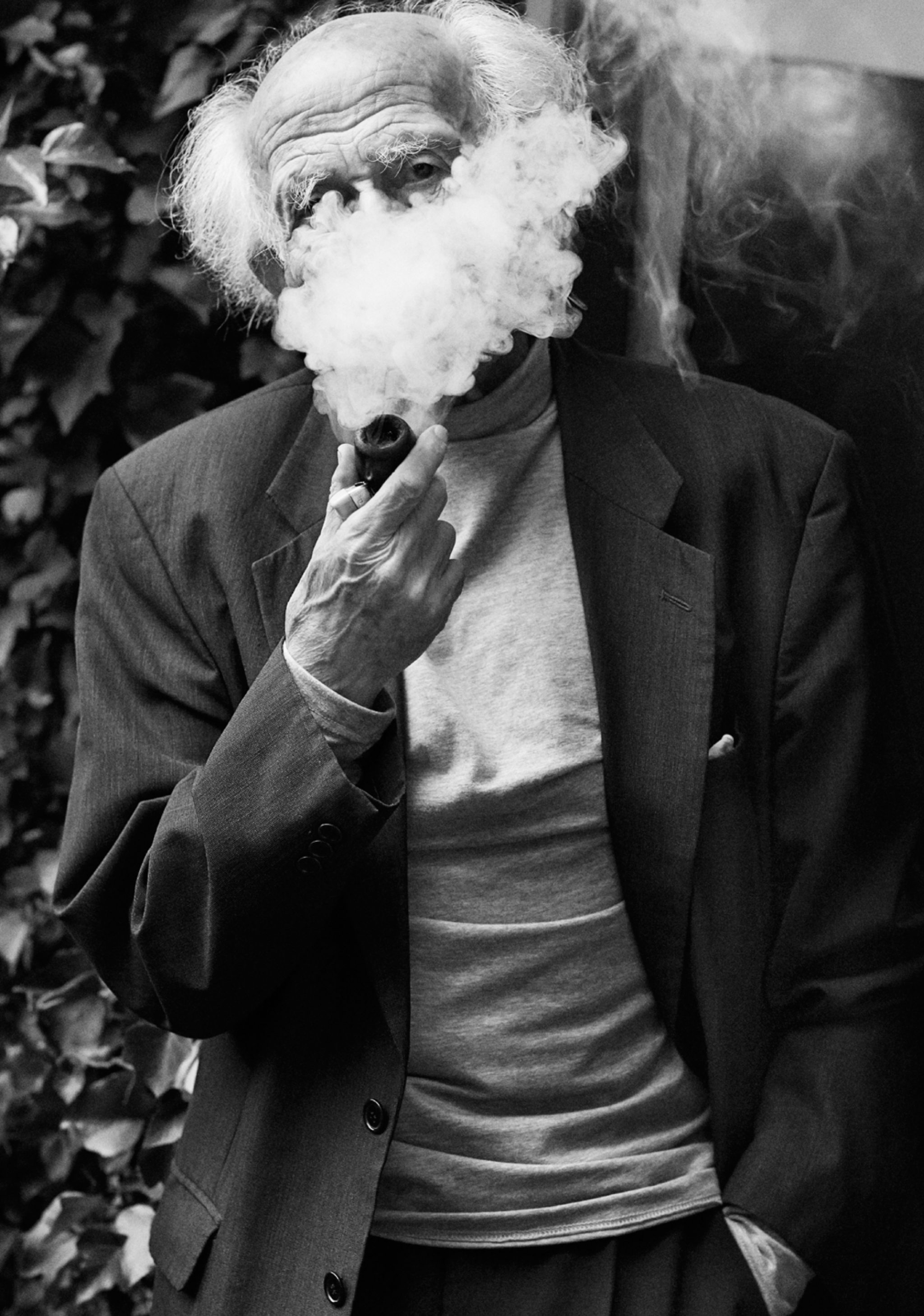

ZYGMUNT BAUMAN: LOVE. FEAR. And the NETWORK.

All Networks Lead Through Kansas: The Shadowy Well(ness) of Masculinity

Mire Lee’s Fountain of Filth

The Art Institution of the Future

Maggie Dunlap’s Teenage Murders

Who Is an American Artist?

Reinventing Mike Kelley

The Denatured Machine

The Politics of Beauty: Tyler Mitchell