The Art Institution of the Future

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

What does the future of the art institutional landscape look like? If you ask Madalina Stanescu—one of the co-founders of the Berlin-based art and club collective TRAUMA (formerly Trauma Bar und Kino)—it could be a space with no labels attached. A space where site-specific art installations and club nights until 6am can take place simultaneously. TRAUMA’s aim is to present alternative models for Berlin galleries, art institutions, and clubs, and be part of an interdisciplinary dialogue between art, music, and performance.

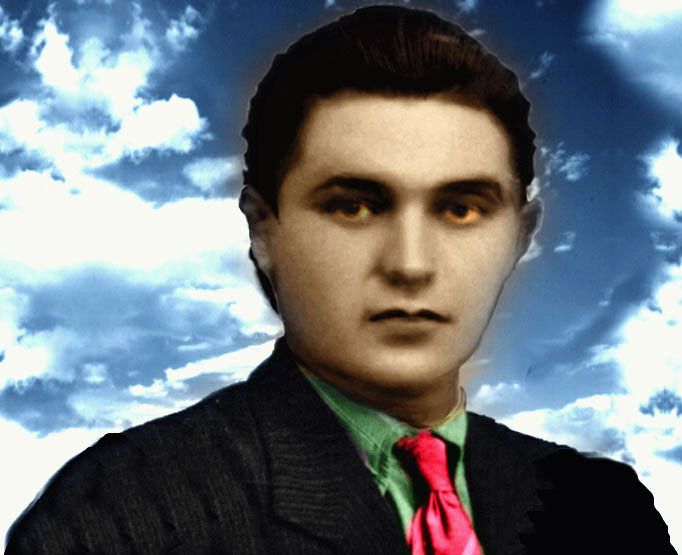

Esben Weile Kjær, “Milky Way,” 2024. Displayed at Trauma, Berlin.

In this interview the members of TRAUMA, Madalina Stanescu, Kyle Van Horn, and Troels Primdahl, are in conversation with Claire Koron Elat about going against the standard music industry, being reduced to a club only, and the “pics or it didn’t happen” ideology.

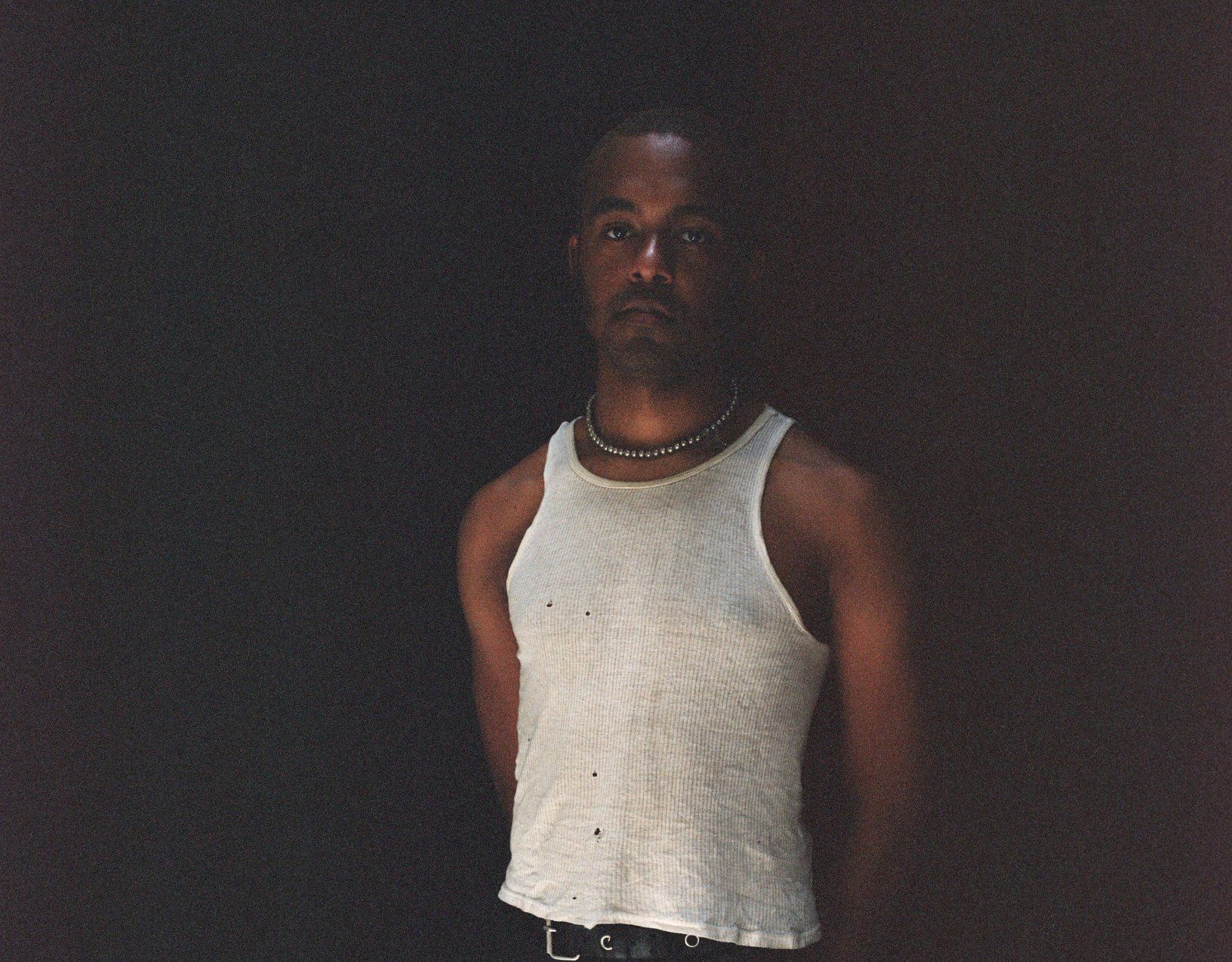

Right to left: Troels Primdahl, Madalina Stanescu, Kyle Van Horn. Photographed by Tobias Kruse.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: You operate at the intersection of club, performance space, and exhibitions. How does TRAUMA identify itself as a space, particularly given that your former name include the words “bar” and “Kino”?

MADALINA STANESCU: Over the years, we have transformed, and we’ve taken different shapes and forms. The name itself is rooted in the initial concept, because Trauma had a small, 56 seat, boutique cinema with a digital and analogue projector. We had a curated cinema program at the very beginning and slowly it became part of our club nights. It brought a very special experience to the club nights because there were multiple visuals screened. In early 2020, we changed the space because of soundproofing matters. The theater space we have right now can still operate as a cinema. And the bar is very straightforward—we have two bars in the space.

KYLE VAN HORN: The bar and kino are a relic of our origin story. I mean, it’s cute, it’s quirky, but it doesn’t really reflect what we’ve done over the last six years. We’ve been pretty deep into this project and gone through a lot of changes. Now we have different ambitions than we did in the beginning. Ditching the “bar und kino” in our name and moving forward as TRAUMA opens us up to be more of a creative concept that can be applied to all sorts of different spaces. We’re really looking forward to expanding to different locations internationally and applying our concept elsewhere.

MS: Yeah, it’s what we did with our birthday event Private Party in May, or with Eartheater and Anna Uddenberg in Basel, or the project with Neue Nationalgalerie. We don’t identify with the space. We are a concept. We are a curatorial collective and a production house.

CKE:Was there a specific point when your ambitions changed?

MS: They are ever changing. I think they’re changing while we speak.

KVH: Our aesthetics have changed, morphed, and switched with time. Everything has developed cohesively into emancipating ourselves from the bar und kino and being more flexible with our concept.

Esben Weile Kjær, “Milky Way,” 2024. Displayed at Trauma, Berlin.

CKE: Heidestraße is not known as a place to go out or as a cultural or gallery hotspot, yet you’re located here. Is this intentional?

KVH: Our location has proven to be a unique filter for our audience. It’s unintentional, though. The most significant filter we have is our programming. Whenever you do creative programming, it tends to weed out a lot of event goers that would otherwise want to have a more predetermined or expected experience. Our programming speaks to a certain segment of the creative and creative adjacent community in Berlin. I have heard that as well about the location, that it’s kind of exclusive and it’s kind of secret—but it’s a pretty open secret.

MS: We don’t want it to be secret.

KVH: We are super down to be known by a lot of people, but the location does provide an interesting challenge.

MS: We chose this location because of the size, because of the flexibility, because what we were able to do in terms of interior design there. Whoever resonates with the universe we’re building gets to come.

CKE: How is your process of choosing the artists you work with?

MS: With the project we did in Basel—Eartheater being a high-profile music artist and Anna Uddenberg being a high-profile visual artist—we thought it was a great idea to show these two artists together, especially since they had a previous collaboration. However, this previous collaboration was only accessible to the public via their screens. So, we wanted to show people what they had only experienced through their screens before—a real-life extension of the internet. Everything is really flowing, we get inspired by one artist, make associations, and envision people together. This is how it happens. It’s something organic and also deeply rooted in our personal interests.

KVH: Taste plays a big role. I can’t really comment on the selection of visual artists here because Madalina leads the visual arts department, but I’m heavily involved in the music booking, and we’re always eager to work with contrasts. Essentially, one of the things we really like to do with this project is to try to lift up as many artists as we can. Let’s say we’ll have a really high-profile music booking, but we aim to create a creative lineup that accompanies it, so it becomes a full experience. In a lot of cases, it’s not possible when you’re working with high-profile artists, but we strive for opportunities to do creative event-making, even with a headline artist. The standard music industry isn’t really open to that, so we have to knock on a lot of doors, and we have to push for it. What I mean is, for example, you book a really hyped artist, and their first impulse is to not want you to book alongside them. They want to choose their own supporting acts and things like that. But we try to pursue, as much as possible, artists who are open to collaboration and trust our taste––though it’s obviously a lot of gut instinct and the collective taste of our creative group.

Esben Weile Kjær, “Milky Way,” 2024. Displayed at Trauma, Berlin.

MS: I think we’re making a collage by putting together these artists, and we really try to reflect something about today and about the zeitgeist and what we are actually experiencing. This is what I think every curation should be––a collage of people’s art reflecting today.

KVH: And we’re only putting on stuff we would actually go to if it wasn’t ours.

CKE: When it comes to headliners, do you usually know them personally, which would make the booking process easier?

KVH: It depends. Even if it’s a close friend, if they get big enough, you still can’t book them directly. You have to talk to their agent, talk to their manager––things like this. Now that we are known by enough people in the music industry, they already expect that we’re going to have some level of creative collaboration with them when they get in contact with us, which is really nice.

MS: And it’s also a matter of credibility, because the more we do, the more credibility we have, and the more flexibility there is on the other end.

KVH: There’s a big element of trust there as well. We have a profile now where artists that are way too big to play here actually would like to play here because they want us in their tour schedule––they want to be associated with our project, which we’re really honored by.

MS: And the same goes also for visual artists. The space here on Heidestraße often gets a little bit tight, because the installations we do keep growing in proportion.

KVH: For the opening of our current show, we were working with doubled the capacity of what can absolutely fit at one time in the venue for the attendance on the night.

MS: We had a queue up to the Döner place. It was crazy, and we were very flattered. But this is why we cannot be location-bound.

CKE: You mentioned that you’re intending to go against the standard music industry. How would you locate yourself within this industry? And where would you place yourself within the art world?

MS: We definitely exist in between traditional labels. From the very beginning, the project has strived to go against the classifications of, “This is a club, this is a museum, this is a gallery, this is a music venue.” I think that nowadays, with the way social media behaves and makes everything so homogeneous, it is a bit anachronistic to talk about spaces with such labels.

KVH: We don’t talk about the visual arts and music as separate entities. We each speak to our own specialties here, but since we’re one team and one curatorial collective, these boundaries are always being mixed. For example, there are still people who think that we’re a club. You also used the word “club” a few times, and that’s totally chill, but we’ve actually never identified ourselves as a club.

MS: Just because it shows club content, does it have to be a club?

Esben Weile Kjær, “Milky Way”, 2024. Displayed at Trauma, Berlin.

CKE: I think if you come from a more conservative art background—like many people from galleries and institutions who visit your space do—as soon as they see that you’re hosting club nights and you have Shygirl playing there, it immediately becomes something different than a traditional art show, and in this case something club adjacent.

MS: But then we’re also doing art shows…We’re presenting performances, art exhibits, and we’re featuring Shygirl and organizing club nights. Where does the label fall?

KVH: Most institutions do end up labeling themselves as one thing or another, and that’s something our programming has shown that we don’t want to do. Our ambitions, capacities, tastes, and everything else don’t fit well into one category.

MS: What makes our curation so special is that we invite our visual artists to co-curate the music program for the time their shows are on, so people can really immerse themselves into the universe of the artist.

KVH: After all, the inspiration and aesthetic upbringing of many visual artists involves a lot of music. They tend to be very nerdy and have specific music tastes.

MS: Let’s be very ambitious and say we really believe that the art institution or cultural institution of the future looks like this.

CKE: In our contemporary Instagram age, people very much feel the need to document art and post it online—it’s almost as if, if you don’t post that you went to the exhibition, you weren’t really there or you didn’t truly appreciate it. What do you think about that?

MS: Kate Brown has a really good article about this. We’ve rejected the idea that social media reproductions are better than the real event, right? But since people are constantly bombarded with images, sounds, and information from events around the world, there’s this pressure to create high-intensity experiences—something that people can actually experience firsthand, which matches the overwhelming amount of noise and information they’re exposed to through their phones. With what we do, people don’t just scroll past the whole thing; they experience it for themselves firsthand.

KVH: We’re definitely in a “pics or it didn’t happen era.” As long as we can all agree that photo documentation or video documentation of an event or an exhibition will never accurately represent the experience in real life, then all this documentation can just be a tool to grant access to people who can’t make it, who don’t live nearby, and who otherwise can’t attend the event. So, I think it’s a good tool, but I understand the shift. Do we prioritize the photo moments, or do we prioritize the experience on site? For us, content has always been the priority, and the artwork has always been what we set our focus on first and foremost. The rest of it, the promotion and post-promotion, has been something we’ve learned to do along the way. I feel like for a lot of what I see online, the photos are probably more interesting or more impactful than the event itself.

MS: It shouldn’t look better on camera than it feels in real life.

Esben Weile Kjær, “Milky Way,” 2024. Displayed at Trauma, Berlin.

CKE: On the other hand, it could also be a strategy to not allow any images at all.

MS: I mean, that’s a case-by-case issue, I think, because prohibition is such a strange thing. We want our artists to get as much attention as possible—attention that goes beyond just the attendance of that night. So, I think it would be a disservice to the artists if we prohibited cameras.

KVH: It’s always a fine line between documentation and infringing on privacy and related matters. But then, first off, being buried in your phone doesn’t really allow you to experience what’s happening in the moment. It also doesn’t necessarily allow other people to feel as free as they can if they know they might end up in your stories or be documented somewhere they don’t want to be. I think this whole thing about prohibiting cameras or forbidding image creation during events is more about encouraging people to be discreet. Forbidding doesn’t mean that cameras won’t be used by people—they’ll just be more chill about it and won’t make it a big deal. I just don’t believe in abstinence policies for anything. But I still have this kind of utopian vision that everyone can agree on a specific collective vibe for the night, and they won’t do certain behaviors that would fuck it up.

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

Related Content

Harry Nuriev’s Critique of the Industry

As Long as it Lasts: Ari Versluis

Artist and Distribution Master MARCO BRAMBILLA’s Hyper-saturated Pop Iconography

Mire Lee’s Fountain of Filth

“We Cannot Assume False Neutrality”: Wu Ming—from the Luther Blissett community

The Dare Knows What's Wrong with New York

Reinventing Mike Kelley

Making Money From Hiding the Truth with Liam Gillick

HR GIGER & MIRE LEE: Horror, Slime, and Satanic Eroticism

An Exorcism of a Prior Identity: Jasper Marsalis (Slauson Malone 1)

Abusing Technology with Kim Gordon

Art World Resorts: A Remedy for Chronic Anxiety