Welcome To Hell: Ben Ware On Extinction

|SHANE ANDERSON

The end is not nigh, it’s already here. In his book On Extinction (2024), philosopher Ben Ware confronts the end of the world and suggests that we have to face our conceptual stasis and imagine new possible worlds.

Bruegel the Elder, Pieter, The Triumph Of Death, 1562-1563. Courtesy of Museo del Prado, Madrid.

SHANE ANDERSON: You’ve recently published a book about extinction –

BEN WARE: Yes, and it’s the first work in a trilogy. The one that comes after is about violence in the broadest possible sense: aesthetic violence, linguistic violence, violence against nature, and, of course, the ugly jouissance of war. Book three is going to be a philosophy of nature, which is where the book on extinction actually started, and it will be about the relationship between what I call “first,” “second,” and “third” nature; about habit; about madness, and much else besides. This is what I was working on when COVID came along, which of course changed everything, as I discuss in the Preface to On Extinction.

SA: So, your thinking was forced to change direction. What, broadly speaking, is On Extinction about?

BW: Well, the first thing to say is that it’s not a conventional book about extinction. The title might be taken as something of a red herring, since its primary focus is not climate change, species loss, or the so-called sixth mass extinction. These things are all there, for sure, but they’re folded back into a bigger philosophical, psychoanalytical, and political narrative. Very simply put, the book does two things. It provides a new philosophical history of extinction, looking at the ways in which extinction has continued to fascinate and provoke thinkers from Kant and Hegel through to figures in the twentieth century such as Adorno and Freud. The idea here is that the history of modern European philosophy can, in one sense, be re-read as a history of thinking about extinction or the end of the world. And the other thing the book does, or at least one of the other things, is to rethink the relationship between time and catastrophe. Nowadays, we hear a lot about tipping points and doomsday clocks. I argue, however, that the catastrophe is not some existential dark cloud still looming on our horizon. It has, in one respect at least, already taken place; and it’s already having a clear effect on our economic, social, and political life. And so, the question becomes: how do we think and how do we act when it’s already too late?

SA: What do you think we should do?

BW: I think this is a crucial question, and it’s one that the book provides a number of answers to. To pick up just one thread: one of the arguments I make is that we need to return to the issue of time. Temporally speaking, we now appear to find ourselves stuck within an arrested time: an ever-expanding present, that has the character of a strange limbo state. We thus need to ask how we might emerge from this condition of stuckness? How might we imagine new forms of collective time opening up? The German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin points us in an interesting direction here, I think. His argument, which I develop in my own way in the book, is that we need to think about moving into the future not as a leap into some great unknown, but rather as a process that involves the repetition and completion of the unfinished past. In this respect, we free ourselves from problematic ideas of “progress” by aiming to actualize alternative potentialities that lie unrealized in history. This all sounds rather abstract, but it has concrete applications, for sure.

SA: In what respect? Can you give an example?

BW: First, we have to look at where the struggles are currently located. The things that are animating younger activists today are, very clearly, issues of ecology and war. And so, I think we should try to imagine how we can build new forms of collective politics—new forms of class struggle—around these particular issues; and then how we might use these as a lever to open up a whole set of other political and ethical debates. But organizing around war, for example, does not involve starting from scratch: it is an effort to begin again the great anti-war protests of 2003 against the illegal invasion of Iraq, which were themselves a kind of repetition of the massive protests against the war in Vietnam. Radical politics thus involves the attempt to bring explosively back to life what has, in one respect, already been started, but to make it appear as if for the first time.

SA: Is Extinction Rebellion a positive example of this?

BW: No. I’m rather critical of them. As I argue in the first chapter of the book, XR exhibit a kind of political masochism, which merely adds to the prevailing culture of the endless end: Spectacle of protest, Arrest by the authorities, Demand that the capitalist state “tell the truth” and “act” in a way that is no longer capitalist—a SAD politics repeated ad infinitum. Their politics is perverse and moves in the direction of what I call apocalyptic jouissance. In the big London protests just before the pandemic, XR activists dropped two banners, both thirty-seven meters long, off Westminster Bridge. One of them read “Climate Change,” the other, simply, “We’re Fucked.” The slogan “Climate Change: We’re Fucked” now appears as an infinitely repeated and endlessly enjoyed slogan; but it is one that should strike us as rather strange, connecting, as it does, the threat of extinction and sexual gratification, and thus perfectly summing up the political impotence of contemporary eco-masochism.

The whole thing is rather absurd. As if politicians are just going to turn around and say, “You’re so right, our preoccupation with growth, our libidinal investment in extractivism, was so, so wrong. What were we thinking?” The eco-moralists seem unable to realize that capitalism is completely indifferent to the moral demand, in the same way that it is completely indifferent to spectacular action. If we want serious change, we will have to think beyond capitalism and not ask it to be nice and benevolent, which it is clearly incapable of being.

Installation view of Hito Steyerl, “Hell Yeah We Fuck Die,” Esther Schipper Gallery, Berlin, 2016.

SA: How do we think beyond capitalism?

BW: I think we might begin by reminding ourselves of Walter Benjamin’s powerful statement: “That things are ‘status quo’”—i.e. that they just carry on as they do—“is the catastrophe….Hell is not something that awaits us, but this life here and now.” I think we need to be aware of what we are up against; and that we cannot expect anything to get “fixed” within the framework of the existing system—and this includes any attempts to “change things from the inside” by so-called “left populists” such as Corbyn and Sanders. This, then, is where the activity of radical critique—or “ruthless criticism,” as Marx referred to it—comes in: critique can itself produce a cut in our present “reality,” a disruption of what we perceive as fixed “second nature.” As part of this activity of critique, we also need to keep alive a number of “old fashioned” ideas, not least the dialectic, totality, and the unconscious: ideas dismissed today as so many relics of an “outmoded,” “paranoid” style of theorizing. If we really want to uncouple from capitalist desire, some kind of synthesis between Marx and Lacanian psychoanalysis will, absolutely, have to be our starting point.

SA: You described earlier that philosophy could be understood through the lens of reckoning with the end. When you said that, it occurred to me that this was something Socrates also suggested: “to philosophize is to learn how to die.” Maybe this is the still the true goal of philosophy?

BW: Maybe. Or maybe, to paraphrase Hegel, the true task of both philosophy and politics today is to look extinction in the face and tarry with it!I think this is what Kant is trying to do in his great, late essay “The End of All Things.” And we can trace a line from here all the way through to Adorno’s comment in his essay “Progress” that the prospect of humanity only opens up in the face of its own extinction. Needless to say, this idea is also present in the great, modernist works of Kafka and Beckett, too.

Cover of On Extinction (2024), by Ben Ware. Courtesy of the author.

SA: And in the history of painting. I’ll never forget this one visit I had to the Prado in Madrid, where people were pushing against one another to get closer to Breughel’s The Triumph of Death. It was like a mosh pit to be near a famous representation of extermination and get a picture of it. This colored my entire experience of the museum and then, from there, I started noticing that so many of these famous paintings—from Goya to van der Weyden to all the depictions of Christ on the cross—were about death. Like your book, so much of culture is about beginning at the end.

BW: Indeed, and this idea of beginning again at the end—and beginning again out of the end—is an idea that I pick up again in the new work on violence. I’ve been going back to the paintings of Francis Bacon, an artist I’ve written on quite a bit—I edited a collection of psychoanalytic essays about Bacon for Thames and Hudson in 2019, and a second collection is forthcoming. And, of course, one sees violence everywhere, but, interestingly, not in the way that Bacon himself describes it. I don’t think that the paintings make a violent impact on the viewer’s “nervous system” as both Bacon and Deleuze believe. I think their violence should be located elsewhere. But that’s another story…

SA: One thing I appreciate about On Extinction is that it brings so many aspects of culture and politics together.

BW: Maybe this is after 10 years of Lacanian analysis, but this is just how I think: which is to say, in a very associative manner, moving constantly between philosophy, politics, aesthetics, ethics, psychoanalysis. Anything to avoid my work lapsing into a kind of “university discourse.” Each section in each chapter offers, or attempts to offer, a new thesis, which means that the book doesn’t have to be read from beginning to end: one can simply read a few sections at a time and take the time to take things in. The rather intricate nature of the construction means that the books can take quite a while to complete; but this is the process, and, right now, I don’t know any other way—I’m sure new formal experiments will emerge over time. In more concrete terms, I think this mixing of culture and politics and everything else comes from a particular modernist impulse that has always animated my work; an attempt to find the new and also find it new! It is interesting that in his final lectures, which were recently published by Verso as The Years of Theory (2024), one of the things that the late Fredric Jameson laments is precisely the disappearance of this modernist impulse from philosophy.

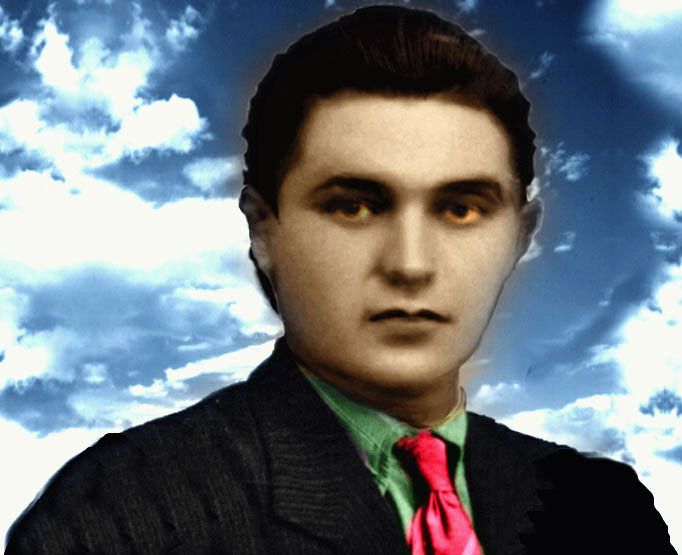

Portrait of Ben Ware. Courtesy of the author.

SA: Since governments and ecological movements are devoid of practical solutions, I’m wondering if you’re sympathetic to technocratic proposals to fixing the crisis through technology, such as cloud bombs.

BW: No, this kind of eco-futurism always raises the immediate spectre of eco-fascism. It gives me the creeps, to say the very least. I come at some of this stuff in chapter three of the book—in a slightly different but related way—when I criticize “de-extinction,” or so-called “resurrection biology,” the use of advanced genetic sequencing to bring back extinct megafauna. As I argue: “de-extinction is perhaps the most extreme instance of the anthropocenic sublime: the attempt to create wonder and awe on the back of global planetary wreckage…De-extinction asks that we put all our faith in accelerationist science to solve all of nature’s woes.” This is a new eco-modernist theology, which turns out to be apocalyptic through and through.

SA: So, you don’t see the government as leading the way nor the technocracts nor the protest movements… Are you an optimist or a pessimist?

BW: What do you think?

SA: That you’re a closeted optimist.

BW: That seems fair. You know, people have picked up the book thinking they’re going to get a very pessimistic tone, but it ends up being politically hopeful. I think there’s a moral obligation to think about the possibility for change. Pessimism can become its own form of negative enjoyment where you can enjoy the dystopia, but this is something I try to avoid.

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON

Related Content

All Networks Lead Through Kansas: The Shadowy Well(ness) of Masculinity

ZYGMUNT BAUMAN: LOVE. FEAR. And the NETWORK.

“We Cannot Assume False Neutrality”: Wu Ming—from the Luther Blissett community

Weaponized Irony: A Roundtable on Trolling and Politics

Abusing Technology with Kim Gordon

“It’s very serious”: BAR ITALIA’s THE TWITS

Mining a Counter-History from the Past: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS and Subcultures in Kansas

Making Money From Hiding the Truth with Liam Gillick

The New American Dream Is Sponsored by Meta: ANA VIKTORIA DZINIC

Image Spamming with Paul Hameline

Life Exists: Theaster Gates’ Black Image Corporation

Are We Artless? NATASHA STAGG