Lankum's Antidote To Alienation

|SHANE ANDERSON

In the middle of their set at the Unsound festival in Krakow, Dublin’s folk-doom outfit Lankum trade quips about the power of hangovers. “Those really bad ones when faces melt,” multi-instrumentalist Ian Lynch says, “are probably the only access we have to shamanism anymore.” People in the audience chuckle, but Ian’s brother, guitarist Daragh Lynch, says it’s no laughing matter, the song they’re about to sing, “On a Monday Morning,” is about the perils of alcoholism. Fiddler Cormac MacDiarmada agrees and notes that the song is by an English singer-songwriter who wrote a lot of drinking songs; and multi-instrumentalist Radie Peat suggests, “It’s terrible, really.”

Lankum photographed by Ellius Grace.

Though just banter between songs, the interaction serves as a synecdoche for the band at large: Taking traditional ballads that occasionally date back centuries, Lankum creates pieces that explore the darkness of the human experience and go against the standard narrative of Irish music, where it’s just about getting drunk and having a good “craic.” At times, the band’s sound is as heavy as a funeral procession and at others it is possessed by a raw, primal energy—thanks, in part, to the Lynch brothers’ background in the European crust punk scene. And although they’ve traded in their electric guitars for traditional instruments, such as Uillean pipes, tin whistle, fiddle, and harmonium, the band nevertheless upends tradition, stripping down the ancient folk songs and rebuilding them with haunting harmonies and dense droning soundscapes that are sweeping festivals and stages across the world, earning them the Guardian’s 2023 best album accolades for their album False Lankum (2023). In this interview with Shane Anderson, band members Cormac MacDiarmada and Ian Lynch explain why traditional Irish music sessions are the antidote to the loneliness of the modern world.

SHANE ANDERSON: The band name used to be Lynched, which was in reference to the last name of two members in your band, but you changed it because you felt it might be offensive to some listeners. Why did you choose the name Lankum?

CORMAC MACDIARMADA: We were on tour in Europe when we landed on Lankum after talking about the name change for a good couple of years. There were hundreds of hundreds of names suggested but Lankum was the one we all agreed on.

IAN LYNCH: We were very fond of a certain recording of a ballad called “False Lankum.” The recording was made by a Traveler singer called John Reilly Jr. in the 1960s in Ireland. He sang this very elaborate, lengthy ballad and the villain of the piece is called False Lankum. It’s kind of like the bogeyman in the story and it goes to a castle to murder everyone, including the children. It turns out that the False Lankum is the one who built the castle and was never paid for his hard work.

SA: So, the song has a very political dimension to it. And it seems to me this could be said of a lot of your work.

IL: It’s just something there in the music. Folk and traditional music is the music of the people.

SA: How do you find the songs you record?

CM: There are loads of different ways. The one thing about music like this is that it’s very much a living tradition, it’s very much in a constant flow. What I mean is it’s not a relic. It’s thriving. It’s very social and vibrant. It’s in the pubs we would have gone to, all the singers circles in and around Dublin as well as in other parts of the country. In the olden days, we would go and play a session, an informal gathering of musicians, after a gig.

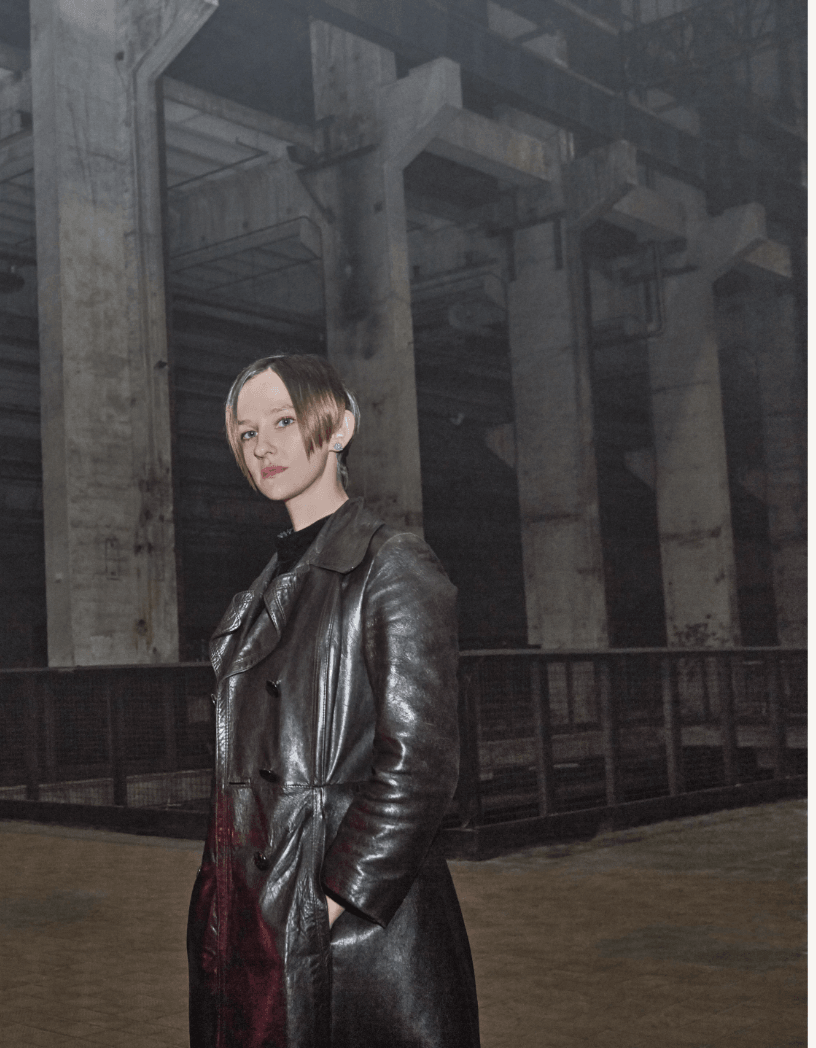

Lankum photographed by Jacob Lillis.

SA: Your sound has changed a lot over the past ten years. What brought about this change?

CM: One of the key things with the last two albums in particular was getting our producer, John “Spud” Murphy, who plays with us now, too. He was on the Dublin Irish scene for a long time and recorded a lot of amazing records. And he brought a different energy that hugely boosts our sound. When we are recording something and are making arrangements now, we’re like, “OK, this is really good, but it’s going to be absolutely stratospheric once he gets his hands on it.”

IL: I think trying to constantly evolve that element of the band’s sound that is darkly meditative is what drives us. But I do think there were certain things we were trying to do previously that were in this direction. Even tracks on Cold Old Fire, say, the middle segment of “Tri-Coloured House,” or, later on, the drone underpinning “Déanta in Éireann” or “What Will We Do When We Have No Money?” We were trying to delve more into doom and drone there and do it with our traditional instruments, but we hit a brick wall before we met “Spud” since these instruments are used in a very specific way.

SA: Another part of your process that interests me is that you decided to record a little-known version of “Wild Rover.” It’s very different than The Dubliner’s version, which feels like Ireland’s second national anthem. Could you talk about that choice and deciding to go against the grain?

CM: When we found that song, it was a bit of a revelation. We were all like, “fucking hell, this is unbelievable.” And that’s half the battle. Once you find one of those songs, it creates a collective energy and drive.

IL: I think it’s safe to say that a lot of people are very sick of that standard version of “Wild Rover.” And so, it’s really nice to bring a different version of the song and use that as an example to say, “Look, a lot of these big traditional songs used to exist in so many different variations around the world. This is only one version and there’s a lot more out there, you just have to dig deeper.” I made a podcast episode about “Wild Rover,” and there are hundreds of versions of that song that exist all around the world. But because of the nature of the recording industry in the 20th century and the nature of mainstream music, when one song is recorded and becomes a hit, it halts this very natural process of variation and evolution that happens to traditional songs when they’re allowed to just exist in their own way in the world. The way that traditional songs change and vary and evolve and travel around the world is important to talk about.

SA: So, it’s about offering a counter-narrative to the boisterous drinking song that is well known?

CM: 100 percent. And you know, the lyrics are fucking depressing. They’re about someone descending into alcoholism and having a huge degree of regret. And that’s not to say that there isn’t a place to have the contrast between the darkest, saddest lyrics with a quite upbeat and merry tune, like in the American Old Time tradition, but we wanted to recontextualize something that is very much a mainstay of the tradition and is done quite a lot and give it a different energy.

SA: What was the reaction like?

IL: I think a lot of people were like, “Holy shit, I’ve heard that song so much throughout my life and I never even realized that it was a song about a person whose life has been ruined by alcoholism and now they have all this regret of a life that’s spent away, and they wish it had been different.” I think people found that really refreshing. I don’t think it would have been the same if we had recorded the “Wild Rover” that everybody knows. The way Irish music has been packaged and sold by the industry is a very one-sided view. It’s all very happy go lucky. We’re all drunk and having a good time. And when we do that, it sounds like this.

As far as we’re concerned, that’s not true to the tradition at all. If you’ve spent time investigating traditional music and song, you find that every single aspect of life is described and comes out in the songs. There are all these other emotions that can be expressed by the music as well.

CM: There is a huge variety out there. I live in Sligo, which has a population of 50,000. A couple of musicians I never met before came to a session that we play regularly and I didn’t know a single tune they played. It’s probably indicative of the huge amount out there and how the repertoire changes from county to county.

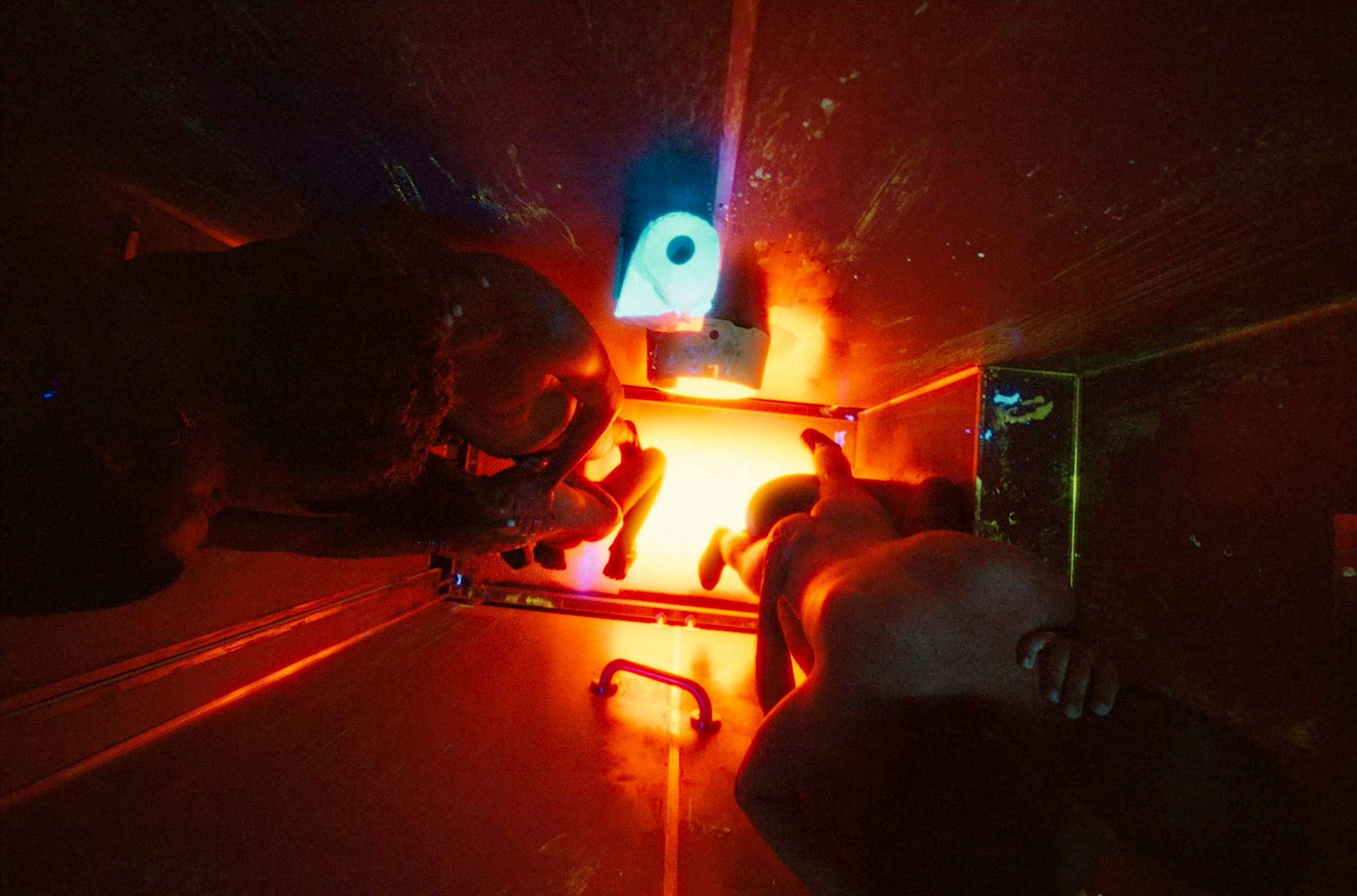

Lankum photographed at Unsound Festival 2024 by Michal Murawski.

SA: It sounds like the tradition is alive and well.

CM: It is… but a lot of places are closing.

IL: Pubs that would have had sessions for a long time around Dublin closed down and a lot of sessions feel a little bit different after lockdown to me. I can’t put my finger on it exactly. But, for all intents and purposes, the music is definitely alive and well. And when you look at the amount of young people who are playing the instruments at a very high standard, it’s definitely safe for another couple of generations at least.

SA: Why do you think people are returning to traditional music?

IL: I think there are a few different reasons. Probably the strongest one is that you can get a depth of satisfaction and very positive feelings and experiences through traditional music that you just don’t get from mainstream culture, where everything is based on having to buy things. It’s like the difference between McDonald’s and cooking a meal at home. One of them is fast and easy and accessible but afterwards you feel a bit sick and still hungry. But the other one keeps you alive and nourishes your soul.

CM: Getting to share in that collective energy is such an important thing. And sessions are one of the few contexts where you can just sit and listen and learn from other musicians in a pub before you play. It’s also free.

IL: As our society becomes more and more insulated and isolated, where most social interactions are online for people, I think it offers a very strong sense of community, and it’s an excuse for people to get together in real life and spend time with each other.

CM: When you live with this toxic aspirational element on social media where you just assume that everyone’s having a good time all the time, it’s very grounding to separate yourself from that and actually engage with others. There’s a release.

IL: And there’s something more to the singing. By singing these songs, you’re putting yourself inside the mind of somebody who existed 200 years ago. You’re thinking about the travails and hardships that they went through, and there’s something very humbling about that. It puts you in check and you get to see through the words of somebody who existed in a very different situation in a different time.

SA: And yet you see how similar we all are in some ways.

IL: Yeah, there’s a reason why a lot of the songs we sing from different eras and areas still resonate with us today. They speak truths that we all experience as human beings in the world and sometimes you’ll come across certain lines or songs and be like, “Damn, that was written 100 or 200 years ago.”

SA: What’s the oldest song you perform?

IL: I think it’s “Wild Rover.” I think the earliest iterations might have been like late 17th century.

SA: Your albums don’t only feature traditional songs made new though. You also have songs that you’ve written.

IL: On every album, we usually have two or three songs that we wrote ourselves. It’s a lot more difficult writing our own songs within the Lankum world because you’re dealing with traditional songs that have been through the greatest filter of all. Every song has probably gone through 20 different people’s brains before it got to you. It’s a constant process of distillation. Folklorists talk about the Darwinian aspect of folklore whereby if something doesn’t resonate with people anymore, if something fails to capture somebody’s imagination, it will get dropped from the song. You can see how a lot of songs shed off verses and became more distilled down to their core emotion. And so, by the time we’re listening to these songs now, a couple hundred years after they’ve been written, they’ve become these really amazing polished nuggets. And that’s a process you can’t really replicate. When you’re writing a song, you’re going back to the very start of that process. Putting these songs side by side with these traditional songs kind of puts more pressure on them than if you were a band that just did your own songs.

CM: When you’re met with infinite possibilities, it can be intimidating.

IL: But it’s also rewarding. We really like to do it because sometimes people forget that the traditional songs had to be written by somebody. Sometimes it’s almost like they just kind of coagulated out of the ether and they’ve always been there. But all songs have to start somewhere. And I think it’s important to keep that process going.

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON

Related Content

The Art Institution of the Future

Where Does The Puppet End And The Human Begin?

Blackhaine: Harsh Realities

Hajime Sorayama: What I Draw Are Human Beings

An Album is a Tragedy: AMNESIA SCANNER & FREEKA TET

L’RAIN: The Musical Doula

Notes From Underground: Slime Fetish

BILLY BULTHEEL and ALEXANDER IEZZI: Sculpting Music in Churches

Disco Isn’t Dead. It Has Gone to War

ON MESSAGE: MATT LAMBERT and ERIKA LUST

CATERINA BARBIERI’s Landscape Listens

ATONAL, Decentered: What is a festival?