Who Is an American Artist?

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

American Artist—whose official, legal name is actually “American Artist”—is concerned with thought experiments that address the history (and present) of technology, race, and knowledge.

“Hey Mom,

I saw your comment on my new blue profile photo. I’m doing an art piece about the present state of social media in our lives, and how the feed we subscribe to dictates our experience in the world […]

Love you :)”

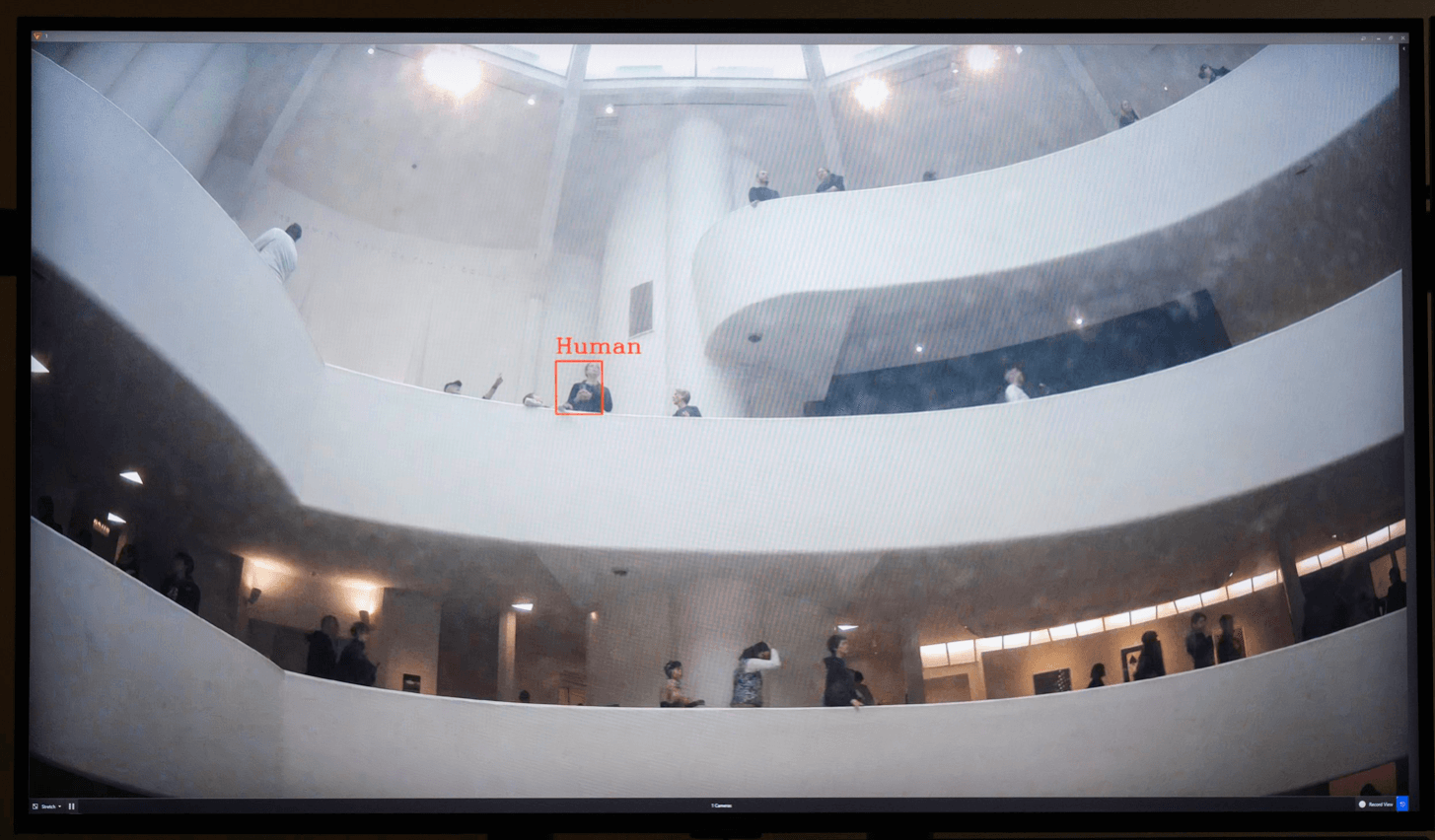

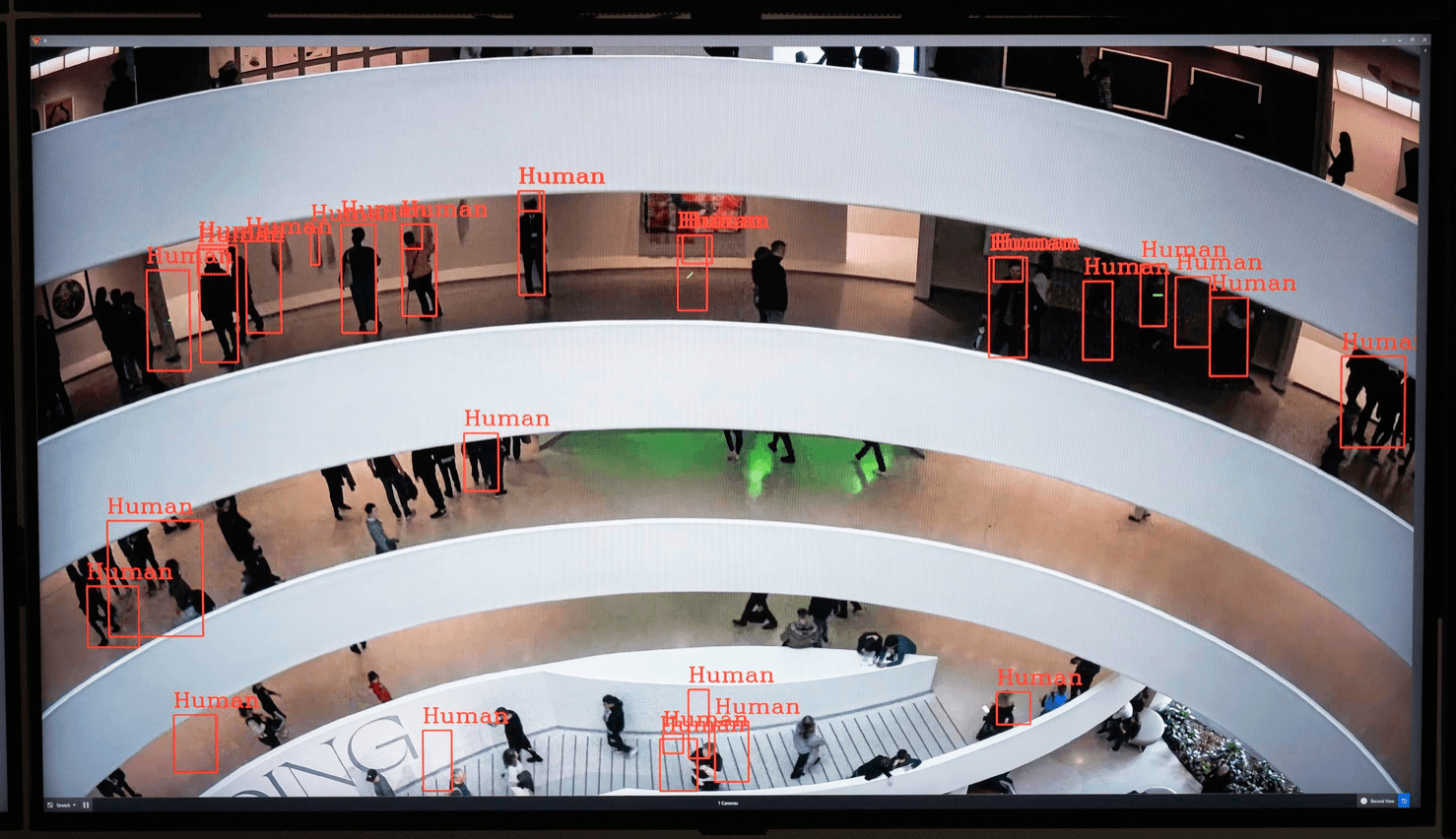

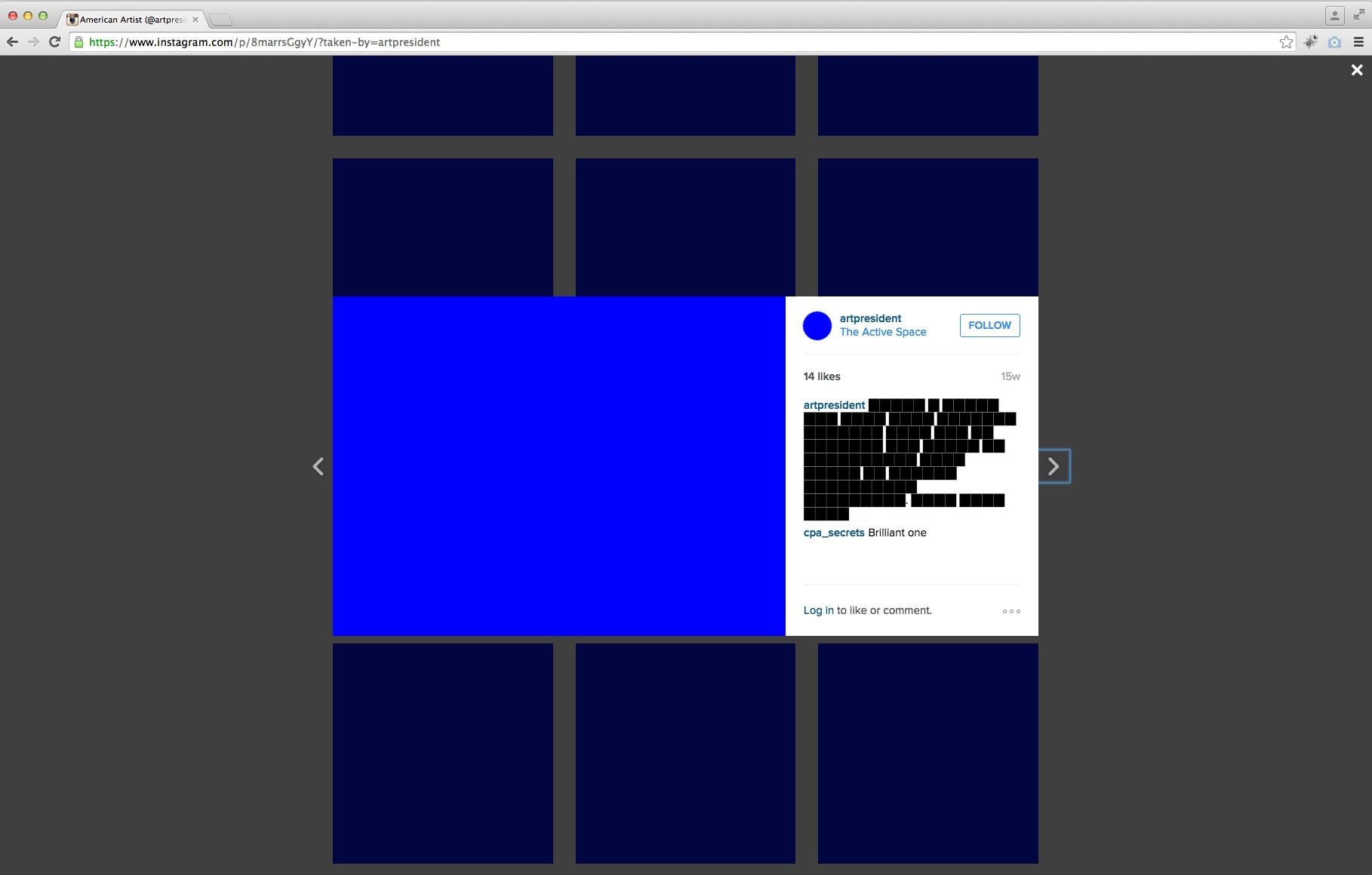

In 2015, American Artist stopped posting regular images on their social media, and instead replaced each photo they would normally post with a blank blue rectangle. If one of their followers wanted to see the actual image behind the seemingly blue void, they had to meet up with the artist in person and go through a physical album. While this work, titled A Refusal, is from 2015–16, it appears to be more current than ever. Our social media feeds design our identity—even the one that takes place outside of digital spaces. So, what’s left when all impressions have been stripped away from this identity?

The practice of American Artist—whose official, legal name is actually “American Artist”—is concerned with thought experiments that address the history (and present) of technology, race, and knowledge. Artist consistently asks throughout their work, how digital software and computer culture can reflect on knowledge, social connectivity, and identity.

In conversation with Claire Koron Elat, American Artist talks about racist and militarized intentions of early computer technology, the user/programmer relationship, and claiming American as part of his identity.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: In 2013, you legally changed your name to American Artist. What are the origins of this decision and in what ways has this name change altered your life?

AMERICAN ARTIST: When I decided to change my name I wasn’t a professional artist in the sense I would consider myself now, even though I was making art. I think part of it came from not knowing how to create a life for myself centered around being an artist, and it came from a place of wanting to manifest it for myself. If I say that I am an American artist, then it becomes true in a way. And I was also thinking about what it means to choose a name for oneself, and how to subvert the protocol of naming conventions. How can I use something that’s readymade and given to us as a standard of how we should move through the world to my advantage? How can I challenge it or turn it on its head?

That’s what I was thinking about when I decided to change my name. As a Black person in America, it’s also interesting to claim American as my identity. Not only claiming it, but acknowledging that, for better or for worse, this is who I am. So, in one sense, being an artist is a crucial part of my identity, but so is being American.

There was also an aspect of, “Why not change my name and see what happens?” I’ve always been interested in the conversations sparked in really mundane scenarios where people don’t know how to respond to my name. That’s when it becomes an artwork or artistic experience, someone having to confront that name or think about it as a person’s name, because usually they think it’s a fake name or they think it’s a glitch in the system. Getting people to see it for what it is, is an extension of the work that I do.

CKE: Do friends and family call you American Artist?

AA: My friends and family call me American. I think it was challenging for some family members. It’s more interesting how it alters my relationship to a stranger meeting me for the first time. That moment of misrecognition or misunderstanding is really fruitful.

CKE: The fact that you have a permanent artist name, for me, alludes to the evergreen question of whether you can separate the art from the artist. Do you separate your persona or identity from the art and the physical objects that you produce?

AA: I don’t think of my art and my life as separate, and I do think that’s something I wanted to tap into through the name change. Recognizing how integrated they are. For me, it felt like art is something that I live and breathe, and so changing my name to that didn’t feel too far removed. It is a way of acknowledging that integration. I’m increasingly trying to build that relationship between my life and my work, because I don’t want it to feel so compartmentalized. I want it to be more fluid and continuous. I want the values that I have in my practice, whether political or personal, to be present in every aspect of my life. So, it’s not like my work is saying one thing and then I’m living a different life. I want it to flow into one another.

CKE: To my understanding, you’re interested in technology, digital softwares, computer culture, and how these fields correlate with knowledge and social relationships, as well as in how we construct our identities based on this?

AA: I would say that my interest in technology in my practice came through my relationship to the internet. I’m part of a cohort of artists that grew up alongside the internet, especially Black artists who have made work using the internet, who have had really formative experiences on the internet. In the particular moment of the 90s/2000s internet, we were seeing it unfold and become something in real time. That’s a moment in history that we won’t ever witness again. Now it’s become commercialized, corporatized, hyper-secure, security focused, and very normative. But there was a time when it wasn’t. It was just an open space to explore one’s identity and connect with other people, and kind of fuck with the system in many ways.

In some of my earlier work, I was really interested in this type of relationship to the internet. I viewed it as an alternative social space that represented values contrasting with what we see in the formal art world. The formal art world is extremely institutional, it’s very classist, and there’s a lot of gatekeeping. And so there was something interesting about the internet when everyone was using it—there was a breakdown of barriers between different people and different social groups. So that’s always been really fascinating to me, and through that, I really became interested in new technologies.

Looking into the history of software and hardware development led me down a rabbit hole where I began to understand the racist and militarized intentions of early computer technology. And this led to my first significant body of work “Black Gooey Universe.” In this body of work, I considered the history of computer technology and how it was designed by a very specific subset of people. And how the decisions that they were making would then go on to inform every device that everyone uses around the world. And so, I was trying to look back at how that happened and why, to point out some of the pitfalls of technology becoming so ubiquitous.

CKE: Would you say that the internet has always been classist? You were saying that, at the beginning, it was an open space for exploring your identity, but at the same time you said that it has been designed in a very specific way and by very specific people.

AA: It was a mix—as with many new technologies. If you think of NFTs, there’s a lot of culture around it, or verbiage that’s used to say that it’s “community-oriented” and that anyone can access it. It feels like that sometimes, like it’s something you could access without already being in the know. But I do think there’s a social space around it that is very prohibitive. It very much centers white male tech workers or tech hobbyists. Even at its best, it often ends up carrying that bias.

You could say within the space of the internet at large, like in the early 90s, it was more open than what it is now, but inevitably, you would still have a similar level of inaccessibility—if someone isn’t able to purchase a computer, it doesn’t really matter how open the internet is socially, there’s a financial barrier to access it. But I would say that, in the early 90s, the internet offered a space of openness that was unprecedented within the realm of technology and doesn’t exist in the same way now.

CKE: What would be your proposition to make the internet more accessible? The question of accessibility is always tricky though since you can quickly end up tokenizing the marginalized groups that you want to include.

AA: I’m not suggesting that it’s possible to bring the internet back to where it was. I think it’s an entirely different thing, because we’re in a moment where the platforms that are considered the most open, such as Instagram or X, are run by individuals who have their own agendas, and the platforms have become politically restrictive. It’s really easy to get censored for certain behavior. With this model that we’re operating under, which is extremely commercialized and privatized, I don’t think it’s possible to have the level of accessibility that was present in the earlier phases of the internet.

CKE: In your work A Refusal, you redacted all texts and images from your social media posts for a year. People had to reach out to you personally and schedule an in-person meeting to see the posts.

AA: The project A Refusal was one of my earliest works that I really felt was intentional. It was not long after I changed my name, and I created it in a moment where I was thinking about the ability for a social media platform to permeate the boundaries of a physical institution. Before that, I’d been posting artworks on Facebook, and asking my friends to look at them wherever they were, as a way to challenge this idea of needing to be in a specific place in order to experience the work.

With A Refusal, I wanted to use that same context but do something more conceptual, something that would challenge people’s idea of how we’re meant to operate within social media, because there is an expectation for you to perform in a certain way and produce certain content. As users of these platforms, we are the product. So, what does it mean to intentionally use the product but challenge it in a way that is visible and conspicuous within the platform itself? Rather than just leaving the platform, how can I, within the platform, make it clear that there’s been a redaction or a refusal to participate?

I used a solid blue image. It’s the blue you see on a computer screen back in the day on Microsoft when it would malfunction, you would get the “blue screen of death.” To me, that blue represents the possibility of another image appearing after we see it. So, for every image that I would have posted on social media, I posted a solid blue redaction instead. I printed out the actual photos, put them in an album, and told people they could see the photos if they reached out to meet me in-person, as a way to reinvigorate the social part that was missing from social media. I thought, “how can I force a real interaction out of this?”

I didn’t get that many requests to see it. It was a couple of professional people that were curious about it, but mostly, it offered a meditative experience for myself and friends who would see the blue come through their screens. They described it as a palette cleanser. Every now and then, amidst all the bullshit on your screen, you would just get a blank blue image, and it would take you out of your trance.

CKE: Especially with the internet and social media, identity and identity building has never been so fragile. It is constantly being stimulated by a myriad of options of how to design yourself. Boris Groys wrote an interesting essay about this called “Self-Design, or Productive Narcissism,” where he claims that we cannot be certain of our own taste today, we are unable to like ourselves if we are not liked by society, whereas in the past the narcissist was able to identify himself with an objective perspective. How would you apply this to a context of looking at marginalized communities and Black people, who are historically not liked by society?

AA: I think we’re no longer in a context where social media feels like a new concept. I think it’s become normalized to the point where people can comfortably choose not to participate and there’s less judgment around that. I feel like everyone’s relationship to social media is becoming more organic and reflective of their own desires.

Earlier on, I think people felt obligated to be public and not participating was really shunned. And since it’s becoming more organic, people are able to shape their identities more holistically and realistically. For that reason, at least in what I’m experiencing personally, I feel like my real-world connections outside of the Internet are becoming more important, and so much of what I experience is not reflected in what I put online. As you mentioned, the public is only interested in a certain kind of content. It’s like, if it doesn’t make sense to post, then there’s no reason to post it. But there was a time where the saying was “Pics or it didn’t happen.” If I don’t post it online, it didn’t happen or doesn’t matter. I don’t think that’s the case anymore.

People are realizing the limitations of what can be represented through social media, and so they’re like, if it’s not valuable to social media, that doesn’t mean it’s not valuable to me. It just means I’m not going to bother trying to make it shareable to someone else. I think that this is where Black people, people of color, queer people, and people that typically don’t have spaces created for them within mainstream institutions are recognizing their own power to self-organize or be in community with each other, whether or not that’s considered valuable to some external system like a social media platform.

There’s just less of a desire to perform for this speculative audience or try and fit oneself into the model of what the platform is expecting.

CKE: In an essay, you said that all users can also be considered programmers. I was thinking about this idea in the context of how fashion brands or any big corporations tackle their marketing, for example, of user generated content. The entity that tries to get you to consume basically makes you consume yourself or your own content, which reminded me of your claim that all users also program.

AA: I was thinking about the user/programmer in relationship to early computer programming. There was a time when computer programmers were the only people using computers, so they were the users and the programmers. And when computers became mainstream, there was a desire to make it accessible and usable by someone with no computer-science background. This led to a certain breakdown: now someone was on the backend, doing the complex math and putting it into an aesthetic interface, so that someone on the frontend with no knowledge of that would feel comfortable using it and feel like they have a good understanding of how it operates.

I think that dichotomy was much stronger at that time. Since then, computer-science has become much more accessible, and even if you are on the backend doing higher-level programming, you don’t have access to all the software that you’re using, you are relegated to one specific part of the system.

There’s been a breakdown in the idea of a user and a programmer to the point where everyone has some relationship to both using and programming. Essentially, when you use a computer, you’re doing some amount of programming, even though it’s on a very low level. But the idea of deconstructing the dichotomy is useful for empowering people to feel like they have the authority and the intellectual ability to identify as programmers. So, it’s also about giving people that confidence to consider themselves a programmer. I would relate that to what you described about content creators. There is an idea that, as a content creator, you must pursue existing trends, tap into what kind of content is going to go viral, or do what has been proven to generate the most revenue. At the same time, you have moments where content creators shift the entire energy of the internet, because they figure out something new that no one knew was going to be popular, and now suddenly everyone’s doing it. That’s one of those moments where I would use the analogy of the user becoming the programmer. The person that is seen as the subject of the system masters it and is able to shift it in a new way.

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

- Photography: TEREZA MUNDILOVÁ

- Fashion: ABBY BENCIE

- Production: LOLA PRODUCTION

- Photography Assistant: MATTHEW PERINO

- Fashion Assistant: JACKSON PRUS