ZYGMUNT BAUMAN: LOVE. FEAR. And the NETWORK.

The sociologist holds a mirror up to our generation.

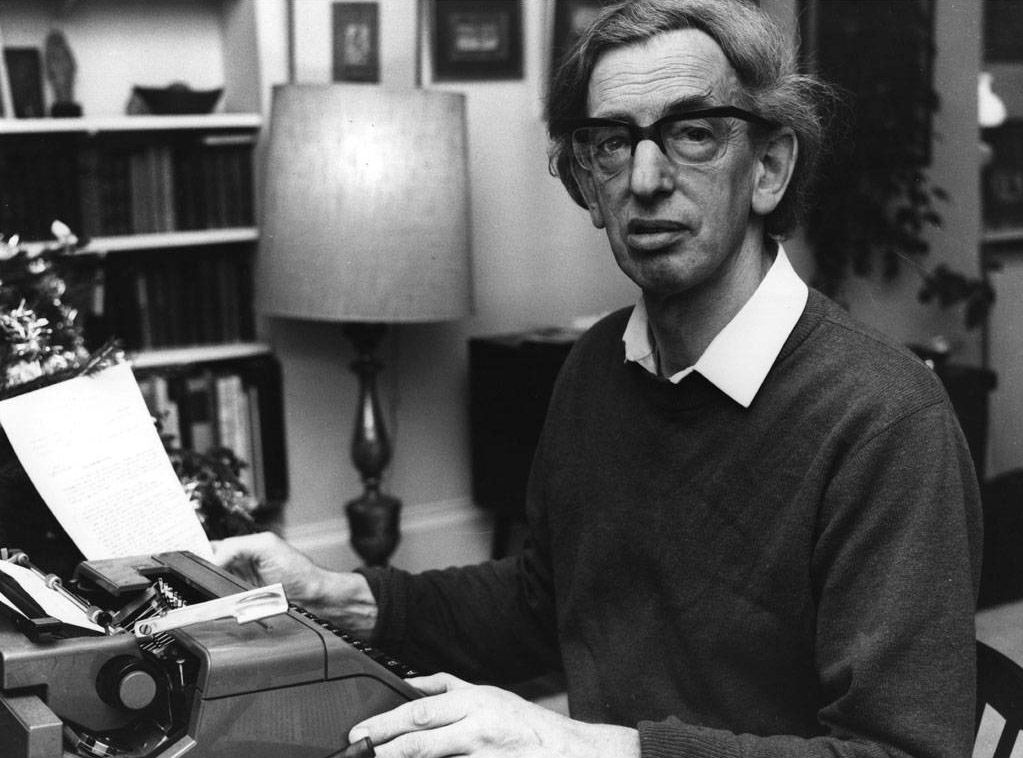

Zygmunt Bauman is without question one of Europe’s most influential sociologists. His oeuvre, read on all continents, encompasses some sixty books, which he has continued to publish at a daunting pace since his 1990 retirement from the University of Leeds in England.

Bauman coined the term “liquid modernity,” which refers to the present state of our society and its transformation of all aspects of life at an unprecedented rate – love, work, society, politics, and power. He has covered a wide spectrum of topics from intimacy to globalization, reality television to the Holocaust, and consumerism to community, extending far beyond his core area of expertise into the fields of philosophy and psychology.

Bauman was born in 1925 into a poor Jewish family in Poznan, Poland, who managed to catch the last train to Soviet Russia and thus saved themselves from a terrible fate. He became a Marxist and fought in the Red Army. After his return to Poland, he served as a political officer in the security corps, fighting against opponents of the regime, and then as an employee in the military’s secret service until 1953. Disillusioned with Soviet communism, he left the Communist Party of Poland. Following a vicious anti-Semitic campaign, he lost his position at the University of Warsaw in 1968 and moved to Israel, where he taught at the University of Tel Aviv for two years before migrating to England.

“The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing,” the Greek poet Archilochus once said. In this famous categorization of writers and thinkers elaborated by Isaiah Berlin, Bauman is both a “hedgehog” and “fox.” He is not a man of details, statistics, surveys, facts, and extrapolations. He paints with a broad brush on a large canvas, provoking debates and injecting discussions with new hypotheses. Yet there is very little in the humanities and social sciences that would leave him with nothing to say. “My life is spent recycling information,” Bauman once said.

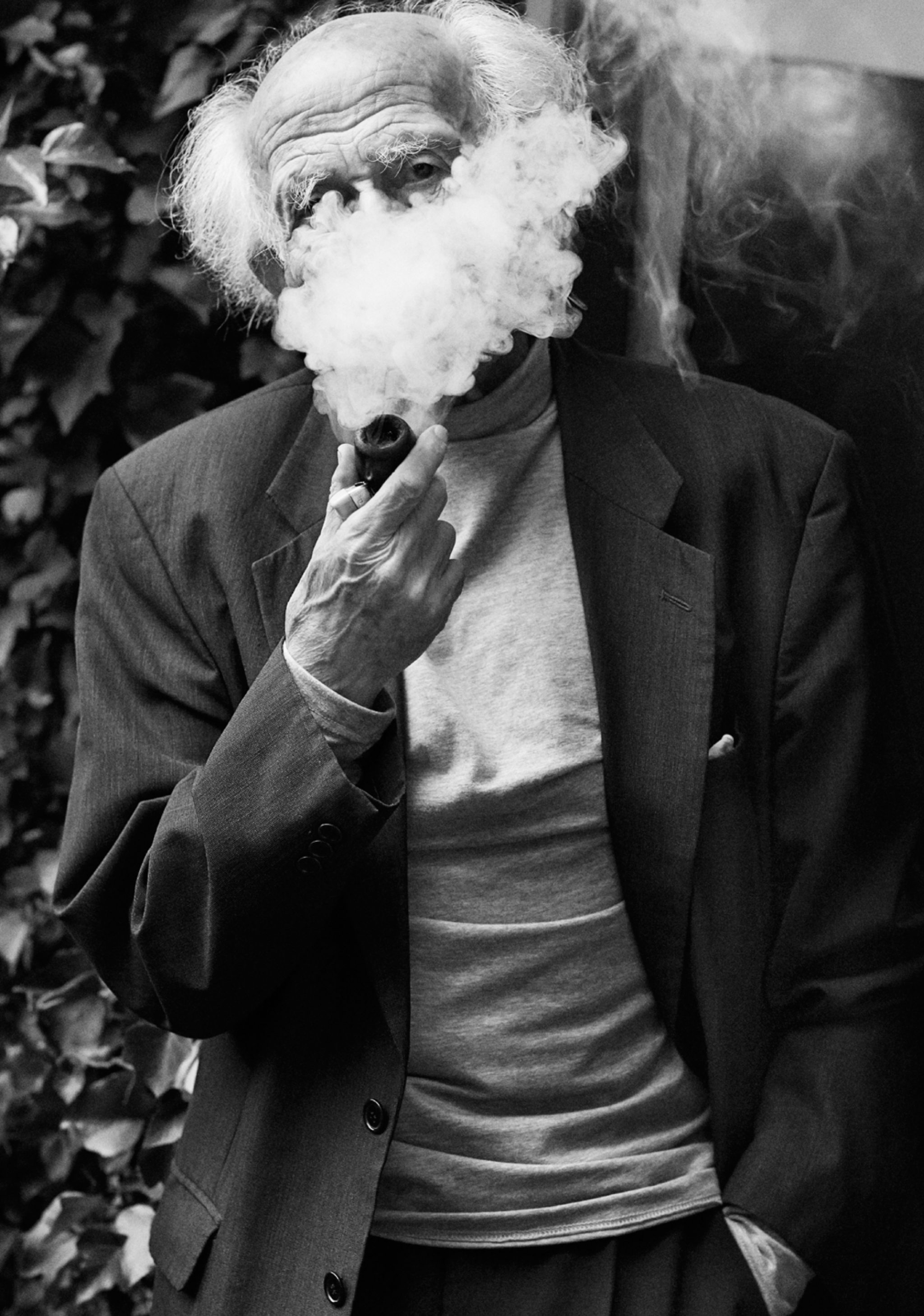

At the age of 89, the sociologist has lost none of his trademark passion for criticism and righteous fury toward the prevailing state of affairs. He still astonishes visitors with a mischievous humor that is not found in the bleak vision of the future in his books. Eastern European to the core, he insists that his guests help themselves to the strawberry tarts, cookies, and grapes laid out before him on the coffee table, surrounded by towering stacks of books. Seated on a worn-out wingback chair with pipe in hand, Bauman takes plenty of time to answer our questions. And this is very much needed, because we want to know: What is life?

Zygmunt Bauman passed away on January 9th, 2017 at his home in Leeds.

Love

Peter Haffner: Professor Bauman, let’s start with the most important thing: love. You say that we are forgetting how to love. What brings you to that conclusion?

Zygmunt Bauman: The trend of finding a partner on the Internet goes hand in hand with the trend of online shopping. I personally don’t like going to shops and buy most things online – books, films, clothing. If you want a new jacket, the virtual store’s website will show you a catalog. If you want a partner, the dating website will also present you with a catalog. The pattern of relationships between customers and commodities defines the patterns of relationships between individuals.

How does it differ from earlier times when future partners met at village fairs or town balls?Online dating involves an attempt to define the features of a potential partner that best reflect one’s own longings and desires. Candidates are chosen based on hair or skin color, height, figure, bust size, age, interests and hobbies, preferences and dislikes. The underlying idea is that an object of love can be assembled from a number of measurable physical and social characteristics. In the process, the most decisive factor gets forgotten: the human person.

But even when such an ideal profile is defined, everything changes once you get to know the person. They are much more than the sum of all these external attributes.The danger is that the pattern of relationships is coming to resemble the way we relate to mundane objects of utility. We would never pledge our devotion to a chair. Why would I vow to remain on this chair until my dying day? If I no longer like it, I’ll simply buy a new one. It’s not a conscious process but it’s the way we learn to see the world and other human beings.

You mean that couples separate prematurely.We enter relationships because they promise satisfaction. When we get the feeling that a different partner would be more satisfying, we break off the old relationship to begin a new one. Starting a relationship takes the consent of two people. Ending it only takes one. As a result, both partners live in constant fear of being abandoned by the other, of being tossed aside like a jacket that’s gone out of fashion.

And that’s a misconception, as you write in Liquid Love, your book on friendship and relationships.It’s the problem of “liquid love.” In turbulent times, we need friends and partners who won’t let us down, who are there for us when we need them. The desire for stability is important in life. The 16 billion dollar valuation of Facebook is based on this need to not be alone. On the other hand, we dread the commitment of becoming involved with someone and getting tied down. We are afraid of missing out. We long for a safe haven yet we still want to keep our hands free.

You were married to one woman for 60 years, Janina Lewinson, who died in 2009. What makes for true love?This elusive but overwhelming joy of the “you and I,” being there for each other, becoming one. The pleasure from the fact that you make a difference in something that is not only important to yourself. To be needed, or even irreplaceable, is an exhilarating feeling. It’s hard to achieve, and unattainable when we persist in the solitude of the egoist who acts solely out of self-interest.

THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE NETWORK

The consumer society, you say, makes it difficult to be happy because it depends on us being unhappy.

“Unhappy” is too big of a word in this context. But all marketing managers would insist that they create satisfaction with the products they offer. If that were correct, we would not have a consumer economy. If needs were fully satisfied, there would be no reason to replace one product with the next.

Consumers are also part of the market. Today, as you claim, they too are becoming commodities.

The culture of consumerism is marked by the pressure to be someone else, the attempt to acquire characteristics for which there is market demand. You have to concern yourself with marketing, to promote yourself as a commodity that can attract a clientele. The paradox is that the compulsion is to imitate whatever lifestyle is currently being offered and touted by paid market criers, and hence revising one’s own identity is perceived not as outside pressure but as a manifestation of personal freedom.

That raises the question of identity. According to the French sociologist François de Singly, identity no longer has any roots. Instead, he uses the metaphor of the anchor. Rather than severing your social and paternal roots, which is permanent, the hoisting of an anchor isn’t irreversible or final. What disturbs you about this?

We can only become someone else if we stop being who we were before. We have to perpetually discard our previous self. In view of the continual supply of new options, we soon come to see our old self as outmoded, constrictive, and unsatisfying.

Isn’t there something liberating about the ability to transform who we are?

It’s certainly not a new strategy to turn tail and run when the going gets tough. People have tried this throughout the ages. What’s new is the desire to flee from ourselves by adopting a new self out of a catalog. What might have started out as a self-confident step toward new horizons quickly turns into an obsessive routine. The liberating “you can become someone else” becomes the compulsive “you must become someone else.” This “must-do” sense of obligation has very little to do with the longed-for state of freedom, and many people rebel against it for this very reason.

What does it mean to be free?

Being free means being able to pursue one’s own desires and goals. The consumer-oriented art of living in the age of liquid modernity promises this freedom, but fails to deliver on its promise.

The concept of “generation,” articulated by the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, is barely a century old. What does it mean today?

Its emergence goes back to the harrowing experience of the First World War, which split one generation from another. The resulting rupture in the European identity made the term “generation” one of the most important tools in the investigation of social and political dividing lines. As an objective scientific category, it is based on subjective and highly diverse life experiences. Today, for other reasons, the experiences that define a generation play a minor role, or none at all, for the next generation.

What does that mean in terms of community?

The idea of community has been replaced by the idea of the network. A community is characterized by the fact that it is difficult to enter. For example, not everyone can become Swiss. There are lengthy procedures in place. Withdrawing from a community is similarly difficult, breaking these social bonds takes considerable ingenuity. You have to come up with reasons. You have to negotiate. And even if you succeed, you never know if and when there could be a backlash. On social networks – on Facebook – it’s a different story. It’s very easy to join in and participate. And it’s just as easy to leave.

TECHNOLOGY

The Internet has many good things about it. Social networks were successfully used by democracy movements such as Arab Spring. What’s the downside?

When it comes to destroying something – toppling a government – it can be useful. The weakness of such movements is that they only have vague plans for the day after. Outraged citizens are virtually all-powerful as a demolition force. They have yet to show that they are equally capable of building up something new.

Technical progress has always led to change in society. Today, however, you say it involves more than that. Why?

Because we no longer employ technology to find the appropriate means for our ends, but we instead allow our ends to be determined by the available means of technology. We don’t develop technologies to do what we want to be done. We do what is made possible by technology.

But hasn’t that always been the case? From the invention of the wheel to the fission of the atom, technological advances have been used for all manner of purposes, the good as well as the bad.

It’s a question of dimension. Of course, technology has always influenced the way we live, and changes have often been met with criticism. This was the case when Gutenberg invented the printing press. Among the educated classes, there was a widely held view that it would lead to moral decay. “Then everyone would learn to read,” they complained. They were of the opinion that the lower classes should not be educated, because it would spoil their willingness to work.

But that’s also the case with the Internet. It’s given countless millions of people from poor areas of the world access to education that was previously unavailable to them. So why the complaints?

Historically, the development of technology has tended to occur in small steps. There were innovations here and there, but not on a global scale, not with revolutionary impact, and not in a way that changed all of society and its way of life. Innovations were absorbed and adapted and became part of daily life. Today it’s different. The changes brought about by technology are massive, and they exhibit certain totalitarian tendencies. One of Russia’s oligarchs, Dmitry Itskov, launched his “2045 Initiative,” a research project that aims to make the human brain superfluous. He’s financing the development of an electronic machine designed to think like a human being. Whether it’s actually realistic, I can’t say. But the fact that someone would have an idea like that is a novelty. For the first time, our thinking is threatened by machines.

UTOPIA

After the historical changes of 1989 – the collapse of the Soviet empire – there was frequent talk of the “end of ideologies.” Apart from Neoliberalism and Neoconservatism, this did more or less turn out to be the case. Social-utopian ideas have had their day.

That’s true, but an end to ideologies is farther away than ever. Modernity was based on the conviction that perfection could be achieved in all things through the exercise of human power. By contrast, the mantra of contemporary politics asserts, “There is no alternative.” The higher powers demand that the common people regard reflection on a sound social order as a waste of time. This new ideology of privatization asserts that such things don’t contribute to a life of happiness. Working more, making more money, no longer thinking about society or doing anything for the community – this is what’s required. Margaret Thatcher, the “Iron Lady,” declared there’s no such thing as society, but only individual men, women, and families.

You characterize the historical development of utopian thinking with the metaphors of the gamekeeper, the gardener, and the hunter. The pre-modern posture toward the world was that of a gamekeeper, while the modern attitude was that of a gardener. Now, in the postmodern era, hunters have come to dominate. How does this utopia differ from previous imaginings of modernity?

It’s no longer about conservation and maintenance, or the creation of beautiful gardens, as used to be the case. Today, all people care about is filling their own hunting bag to the brim without concern for the remaining supply of game. Social historians discuss this transformation under the heading of “individualization,” while politicians promote it as “deregulation.” Unlike earlier utopias, the utopia of the hunter doesn’t imbue life with any meaning, either real or spurious. It merely serves to banish questions about the meaning of life from people’s minds.

What are the foundations of this utopia?

We’re dealing with two utopias here that are mutually complementary: the one of the free market’s wondrous healing power and the other of the infinite capacity of the technological fix. Both are anachronistic, envisaging a world with rights, but without duties, and above all, without rulers. They militate against any plan, against the delay of gratification, against sacrifices on behalf of future benefits. The spontaneity of the world conjured up here makes nonsense of all concerns about the future – except the concern about being free from all concerns about the future.

HUMAN WASTE

For you, fashion is an example of what consumer society has made of us.

Fashion revolves around the idea that everything we buy must soon be discarded. There are good clothes that could still be worn, but since they are out of fashion, we are ashamed to be seen in them. At the office, the boss looks us over and exclaims, “How dare you show up dressed liked this?” When children go to school with last year’s sneakers, they’re subject to ridicule. There’s pressure to conform.

Fashion demonstrates how consumer society is specialized in the production of trash. A more serious matter is what you call the “production of ‘human waste.’” Why do you classify the unemployed as rubbish?

Because society no longer has any for use them, and their lives are seen as worthless, just like the lives of refugees. That’s the result of globalization, of economic progress. The number of people who have lost their jobs in the wake of capitalism’s triumphant march across the globe continues to rise unabated and will soon reach the limits of what the earth can handle. With each outpost that the capital markets conquer, the sea of men and women who have been stripped of their land, their property, their jobs, and their social safety nets grows by the thousands, or even millions. This creates a new type of underclass, a class of failed consumers. They no longer have a place in society. We no longer know where to put them now that disposal sites are in short supply and the areas where we used to export surplus workers are no longer available. The success of our democratic social states was long based on this possibility. Today, every last corner of our planet is occupied. That is what’s new about the current crisis.

What about the refugees who come seeking shelter?

Back in 1950, the official statistics already counted one million refugees, most of them so-called “displaced persons” from the Second World War. Today, according to conservative estimates, this figure is 12 million. By 2050, we can anticipate one billion exiled refugees, shunted into the no-man’s-land of transit camps. Refugees, migrants, the marginalized – there are always more of them.

How do we know this isn’t simply a temporary phenomenon?

Becoming an inmate of a refugee camp means eviction from the world shared by the rest of humanity. Refugees are not only surplus, but also superfluous. The path back to their lost homeland is forever barred. The occupants of the camps are robbed of all features of their identity, with one exception: the fact that they are refugees. Without a state, without a home, without a function, without papers. Permanently marginalized, they also stand outside the law. As the French anthropologist Michel Agier notes in his study on refugees in the era of globalization, they are not outside this or that law in this country or another, but outside the law altogether.

Refugee camps, you say, are akin to laboratories in which the new, permanently tem-porary mode of living of liquid modernity is tested.

In the globalized world, asylum seekers and so-called economic refugees are the collective likeness of the new power elite, who are actually the true villains in this drama. Just like this elite, they are not tethered to a fixed location. They are erratic and unpredictable. Governments aid and abet popular prejudices because they don’t want to confront the genuine sources of existential uncertainty troubling their electors. Asylum seekers take on the role that was previously reserved for the witches, goblins, and ghosts of folklore and legend.

In the course of this development, you say the social state has become a security state. What distinguishes the two?

The social state takes a community based on inclusion as its model. The criminal justice state does just the opposite. It’s about exclusion from society by means of punishment and incarceration. The security industry then becomes one of the most important branches of waste production, responsible for the disposal of human waste.

The right-wing parties that exist just about everywhere in Europe have accelerated this development. They’re supported by media that gives a platform to scaremongering, talk about “overpopulation,” and linking issues of “asylum” and “terror.”

The success of radical right-wing parties is based on a fact that is visible: immigration. And everything gets traced back to it. Why is there unemployment? Because of immigration. Why is the education in our schools so bad? Because of immigrants. Why is crime on the rise? Because of immigrants. “If only we could send them back where they came from, all our problems would be gone.” That’s an illusion. There are more important reasons to be afraid than a few thousand – or a few hundred thousand – immigrants. But it works. It’s a psychological consolation: “I know what ills me. I have something that I can attach my fears to.”

FEAR

Fear, you write in your book Liquid Surveillance, is the defining sign of our times. Society’s attempts to protect us from fear only end up producing more of it. Weren’t the fears of the past worse – the fear of God, the Devil, Hell, ghosts, and nature?

I don’t think people’s fears today are greater than they used to be. But they are different, more arbitrary, more diffuse, more nebulous. You work for a company for 30 years, you’re held in high esteem, and suddenly a bigger corporation swoops in, swallowing up the company. It gets stripped down and sold off, and you find yourself on the street. At the age of 50, the prospects of finding a new job are limited. Many people fear such blows and adversities, not knowing from whence they might come and not being able to take any precautions to prevent them.

And it used to be different?

People were afraid of something concrete. The crops were failing, and people looked to the heavens, “Would the rain finally come, or would it stay dry and make everything wither away?” Children went to school, but had to pass through a small forest where a wolf was known to roam, so they had to be escorted through the woods. Even during the fear of nuclear war, people believed they could protect themselves by building bunkers. Of course, that was foolish, but they still thought they could do something. People didn’t despair. They said to themselves: “I’m fine. I’m building a bomb shelter for my family.”

At least in the wealthy part of the world, we are living longer and more safely today than any society before us. The risks have become much lower.

You have to compare the concept of risk to the concept of danger to make the difference clear. Danger is specific. We know what we are afraid of and we can take precautionary measures. That is not the case with risk. Many theorists have noted the paradox that our lives are much safer today than any generation before us yet, at the same time, we live under the phantom of insecurity. The modern variant of fear, it could be said, is defined by the fear of human evil and human evildoers.

From which a whole industry benefits.

The security industry is the ultimate growth industry, the only industry that’s completely immune to economic crises. It has nothing to do with statistics or current threats. International terrorism is a very good pretext for expanding security forces and enacting tougher measures. The number of victims of international terrorism is ridiculously small compared to the number of road accident fatalities. There are so many people killed on the roads, and the media doesn’t even talk about it.

Every car should have a sticker on it, like the ones on cigarette packages: “Driving a car endangers your health and the health of those around you.”

Yes, exactly! On the other hand, the standard of living has gone up. We no longer have to think about bread-and-butter issues in our part of the world. At the same time, the latest financial crisis has made people more afraid of falling into poverty. The entire middle class is subject to the vagaries of the market, fearing that the standard of living will keep falling and never recover. Not to mention the workers who have lost their jobs. Sure, the standard of living is far higher today than in the nineteenth century, but for some reason it no longer engenders feelings of happiness. Even after quite good days, many go to bed and suffer nightmares. Devils come forth that were suppressed during the day, because people were too preoccupied with their jobs. Then, in the still of the night, the fears rise to the surface.

Depression, you say, is the defining psychological affliction of consumer society.

In the past, people suffered from a profusion of prohibitions. The dread of indebtedness, the fear of accusations of nonconformity following a breach in the rules – all these things caused neuroses. Today, we suffer from a surfeit of possibilities and the terror of inadequacy, which leads to depression.

POLITICS

Power and politics, you argue, have fallen apart today. How did it happen to be so, and what does that entail?

When I studied more than half a century ago, the nation-state was still the supreme institution. It was sovereign – economically, military, and culturally. That’s no longer the case.

Why do we no longer believe in the state?

In the 1970s, the state became unpopular because it wasn’t able to live up to its promises. The welfare state couldn’t be fixed. It didn’t have enough resources, and people were tired and fed up with the state deciding everything and depriving them of their freedom. But there was a miracle looming on the horizon: the free market. “Let’s deregulate, privatize. Let’s trust the invisible hand of the market, and everything will be fine.” That was the thinking.

If it wasn’t already damaged before, this trust was definitively shattered by the most recent financial crisis.

The collapse of the credit system and the banks in 2007–08 is different from the crises of the 1930s and 1960s in the sense that we no longer believe in the state, or in the market. That’s why I call this period an interregnum, in the modern sense of the word as employed by the Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci. He defined the interregnum as a period in which the current ways of doing things no longer work properly, but new alternatives have not yet been invented. We’re living in such a period today.

And how can we find our way out of this?

We know what we don’t want and we run away from things that don’t work. But we don’t yet know where we’re running to. A recently published book by the sociologist Benjamin Barber with the provocative title If Mayors Ruled the World is very intriguing. Barber’s idea is simple. The changes that are necessary cannot be carried out at the state level, or the level of “life politics.” When the nation-state emerged, it was an instrument for gaining independence. But our problem today is that we all depend on one another, and the sovereign territorial state is incapable of tackling interdependent problems. That is also true of “life politics,” which saddles the individual with the responsibility for social problems. Problems at the planetary level certainly can’t be solved in this way, because neither you nor I – and not even the super rich – have the resources to do so.

THE MURDERER INSIDE US

In your book Modernity and the Holocaust, you advocate the provocative thesis that the idea of exterminating human beings on an industrial scale is a product of modernity – not specifically of German nationalism. So would Auschwitz still be possible today, and if yes, under which circumstances?

The modern age is not an era of genocide, but has simply enabled modern ways of carrying out such categorical mass killings. Thanks to innovations like factory technology and bureaucracy, but especially thanks to the ambition that the world can be changed, even turned upside down. People no longer have to accept the idea, as believed in medieval Europe, that God’s creation forbade people from meddling, even if something was not to their liking. In the past, you simply had to endure it.

We can remake the world exactly as we wish.

For the very same reasons, the modern age was also an era of destruction. The striving for improvement and perfection called for obliterating countless numbers of people deemed unlikely to be accommodated in the perfect scheme of things. Destruction was the very substance of the new. The annihilation of all imperfections was the condition for achieving perfection. The attempts that stand out from the rest in this regard were the projects undertaken by the Nazis and the Communists. Both sought to eradicate once and for all every unregulated, random, and control-resisting element or aspect of the conditio humana.

But people in earlier eras, such as the time of the Crusades, committed murder in the name of God?

The ambition of the modern age is to bring the world under our own management. Now, we are at the helm, not nature, not God. God created the world. But now that He is absent or dead, we must manage it ourselves, make all things new. The destruction of European Jews was only part of a larger project: the resettlement of all peoples with the Germans at the center – a monstrous undertaking, as dizzying as it was arrogant. One element that was critical to making it a reality is fortunately now absent: total power. Something like this could only be carried out in Communist Russia, or Nazi Germany. In less totalitarian countries like Italy under Mussolini, or Spain under Franco, it wasn’t possible. This element was lacking. God help us that this will remain the case.

The National Socialist project is often understood as just the opposite – as a return to barbarism, as a rebellion against modernity, against the core principles of modern society and not as its fruition.

That’s a misunderstanding. It stems from the fact that these were such extreme manifestations of these principles, relentlessly radical and ready to cast aside any misgivings. National Socialists and Communists did what others also wanted to do at the time – the latter simply not having been determined and ruthless enough – and what we still do today, albeit in a less spectacular and less repulsive fashion.

What do you mean by that?

The distancing of human beings and the automation of human interaction, which we continue to engage in. The most seminal effect of progress in the technology of distancing and automation is the progressive, and perhaps unstoppable, liberation of our actions from moral scruples.

HAPPINESS

In your book The Art of Life, you talk about happiness, a subject addressed by the life philosophers of antiquity. In the modern era, happiness has become a thing to be chased after.

It started with the American Declaration of Independence in 1776, which proclaims “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” as inalienable, God-given human rights. Of course, human beings have always tended to be happy rather than unhappy. The pursuit of happiness was endowed in us by evolution. Were that not the case, we would still be sitting in caves instead of these comfortable armchairs. But the idea that each and every one of us has the right to pursue it in our own way has only existed since the modern era. The proclamation of a general human right to individual happiness marked the start of the modern age.

But it is seemingly no less difficult to attain happiness today than during Roman times, the era of the life philosophy of Seneca, Lucretius, Marcus Aurelius, and Epictetus. What does happiness mean to you personally?

When Goethe was around my age, he was asked if he had a happy life. He responded, “Yes, I have had a very happy life, but I can’t think of one, single happy week.” This is a very wise answer. I feel exactly the same way. In one of his poems, Goethe also said there isn’t anything more depressing than a long stretch of sunny days. Happiness isn’t the alternative to struggles and difficulties in life. The alternative to that is boredom. If there aren’t any problems to be solved, no challenges to be met that occasionally exceed our capabilities, we become bored. And boredom is one of the most widespread human afflictions. Happiness – and here I see eye-to-eye with Sigmund Freud – is not a state but a moment, an instant. We feel happy when we overcome adversity and misfortune. We take off a pair of tight shoes that pinch our feet and feel happy and relieved. Continuous happiness is dreadful, a nightmare.

We are all artists of life, you say. What is the art of living?

Attempting the impossible. Understanding ourselves as the product of our own creation and making. Acting like a painter or sculptor and confronting tasks that can scarcely be accomplished. Setting objectives that exceed our own possibilities at the moment. Attaching standards of quality to all the things we do – or could do – that lie above our present capabilities. Uncertainty is the natural biotope of our existence. Even if the hope of transforming it into the opposite is the driving force behind our pursuit of happiness.

You not only theorized about the transition from “solid” to “liquid” modernity, but you also experienced it first hand. What did you want when you were young?

As a young man, like many of my contemporaries, I was influenced by Sartre’s idea of a projet de la vie. Create your own project for life and move toward this ideal, taking the shortest and most direct path. Decide what kind of person you want to be, and then you have the formula for becoming this person. For each type of life, there are a certain number of rules we have to follow, a number of characteristics we must acquire. From beginning to end, as envisioned by Sartre, life proceeds step by step along a route that is determined in its entirety before we even start on the journey.

THE FUTURE

You are very critical of our contemporary society, and from time to time glimpses of the Marxist you once were come shining through.

I discovered Antonio Gramsci, whose philosophy granted me an honorable discharge from Marxism. But I never became an anti-Marxist like many others. I learned a great deal from Marx. And I am still attached to the socialist idea that a society should be measured by the quality of life of its weakest members.

On the other hand, you’re also a pessimist. The power of the new capitalism is so great that there’s very little room for an alternative. Is that not cause for despair?

After my lectures, members of the audience have been known to raise their hands and ask why I’m so pessimistic. It’s only when I talk about the European Union that people ask why I’m so optimistic. Optimists believe this world is the best of all words. And pessimists fear the optimists are right. I don’t belong to either of these two factions. There is a third category in which I count myself: the one of hope.

How does this fit with your admiration of Michel Houellebecq, perhaps the most depressing writer of the present day?

I like Houellebecq because of his sharp eye and his knack for detecting the general in the specific, to uncover and extrapolate its inner potential, as in his The Possibility of an Island, the most insightful dystopia to date of a deregulated, fragmented, and individualized society of liquid modernity. He is very skeptical and devoid of hope and provides many reasons for his assessment. I am not fully aligned with his position, but I have a hard time refuting his arguments. It is a dystopia that can be compared to Orwell’s 1984. Orwell wrote about the fears of his generation, while Houellebecq describes what will happen if we go on like this. The last stage of loneliness, separation, and the meaninglessness of life.

Where does hope remain?

Something tremendously important is missing in Houellebecq’s portrayal. The powerlessness of politics and the powerlessness of the individual are not the only culprits to blame for the bleakness of the present outlook, and precisely because of this, the current state of affairs doesn’t preclude the possibility of a reversal. Pessimism – that’s passivity, doing nothing because nothing can be changed. But I’m not passive. I write books and think and I’m passionately engaged. My role is to warn people about the dangers and to do something about it.

Credits

- Interview & Text: PETER HAFFNER

- Photography: JOHN BOLSOM