All Networks Lead Through Kansas: Is Cyberspace the place?

|PHILLIP PYLE

In this installment of ALL NETWORKS, Phillip Pyle considers the 21st-century space race as a mirror to the issues plaguing the web. With Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos serving as key interlocutors in both discourses, Pyle looks at the social, psychological, and affective conditions that further link cyberspace and space. By centering on Ryan Fiorentino’s exhibition “Habitat for the Human Animal,” in which the artist, architect, creative director, and Head of Advanced Strategy at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory casts himself as an alienated future space traveler, Pyle traces an aesthetic example of a speculative, Post-Internet Art that he calls Post-Space X Art.

Photography courtesy of Ryan Fiorentino

The Alienated Web

The Marxist concept of alienation has long been unsuitable for understanding the more abstract alienation that stalks the internet user today. The content creator, sharer, and lurker not only experiences divorce—within themselves, between themselves, between each other, and their labored product—as a unilateral coercion wrested from web platforms. Instead, something even more ineffable, the notion of individuality itself, is unmoored. In exchange for free access to social media platforms, parts of ourselves are abstracted into data meant to indicate and control desires. Those desires are then sold as a virtuality to commercial advertisers, only to return to the remaining part of ourselves in their desirable pop-up ad commodity form. If this seems a far cry from the utopic vision of the internet, it’s because the internet has devolved into the opposite—a place of interpersonal disconnection, inequitable access, and the shadow-banned dissolution of anti-hegemonic politics.

Under the tutelage of Leviathan-esque techno-billionaires and their political allies, we’ve seen social media platforms surveilled without consent, hate speech propagated under the guise of protecting free speech, the mishandling of data to the point of influencing political elections, and the disregard of public opinion in favor of inciting inflammatory, often PSYOP levels of conflict within shared political causes. Australian academic Julianne Schultz writes for The Guardian: “The tech titans will almost certainly have the most toys when they die in a globe flattened for their convenience. They neither asked permission nor sought forgiveness for the chaos they have delivered.” For Schultz, the roots of today’s tech-abetted evils can be located in the cradle of 1970s neoliberalism, particularly in Milton Friedman’s 1970 essay “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits” and in psychologist B. F. Skinner's research on human behavioral technologies.

Elon Musk wearing an Occupy Mars t-shirt while on stage with Donald Trump at a rally in Butler, PA. Courtesy of Reuters

Post-Space X Art: From Cyberspace to Outer Space

It is from this early 1970s womb of neoliberal thought—and its genetic disposition for privatization, decentralization, and, of course, uninhibited and expansive growth—that a parallel contemporary discourse emerges: the privatization of interplanetary space travel. It was in those post-Apollo 12 years that even some of the most altruistic thinkers around space, who were concerned with both threatening ecological disaster and a dip in NASA funding, began advocating for private space research. Today, that private industry is led by the world's two richest men, Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, who, of course, are two of the principal players in shaping the internet. Beyond the material ties concretized through Musk’s umbrella ownership of X, Space X, and Starlink (Musk’s satellite internet system for space travelers) under X Corp or Bezos’ dual ownership of Blue Origin and Amazon, the renewed push to make humans an interplanetary species is also fraught with the same extractive and colonial relations currently plaguing the web.

However, unlike the internet, which multiple waves of post-internet artists have subjected to psychoanalysis, politicized scrutiny, and aesthetic interventions, today’s current of space research and travel is rarely interrogated through an aesthetic and affective lens. In the same way that the post-internet often foregrounds today’s alienating conditions through playing with the social media image, experimenting with the devolvement of meaning in language, or even inadvertently through, to borrow from Droitcour’s 2014 diagnostic inArt In America, “creating objects that look good online,” it is due time that the same critical artistic inquiries are directed at contemporary space travel. After all, in 2022 alone, the private space economy accounted for 350,000 jobs and 131.8 billion dollars of the total U.S. GDP. With things seemingly fated to trend ever-upward globally (The World Economic Forum predicts that the global space economy will be worth 1.8 trillion dollars by 2035), the future of space travel casts an imminent shadow on the unresolved desires, problems, and questions of today.

In fact, if one really reflects on what Post-Space X genre of art might be, and on what interplanetary space travel would look like beyond merely biological, economic, or technological considerations, they will likely find the same lingering condition of social and psychological alienation that accompanies life online, and thus everywhere, today.

Robert McCall, Opening the Space Frontier - The Next Giant Step, 1979

Ryan Fiorentino and the Role of Aesthetic Intervention

In contrast to the majority of private industry and public research, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) in Pasadena, California has long been concerned with the psychological and social dimension of the future. Originating in the early 1930s, nearly 30 years prior to the founding of NASA, JPL has been known to embody a somewhat sci-fi, speculative relationship to the future.

Ryan Fiorentino, Head of Advanced Strategy at JPL, is a prime example of the interdisciplinarity that guides much of the work at the renowned space future lab. Fiorentino is a social scientist, architect, artist, and creative director. His latest independent endeavor, an exhibition entitled “Habitat for the Human Animal” provides a sort of psychic jolt to the unconscious of current interplanetary space travel narratives that would also greatly benefit other contemporary discourses around the technologies of the future, especially those around the web.

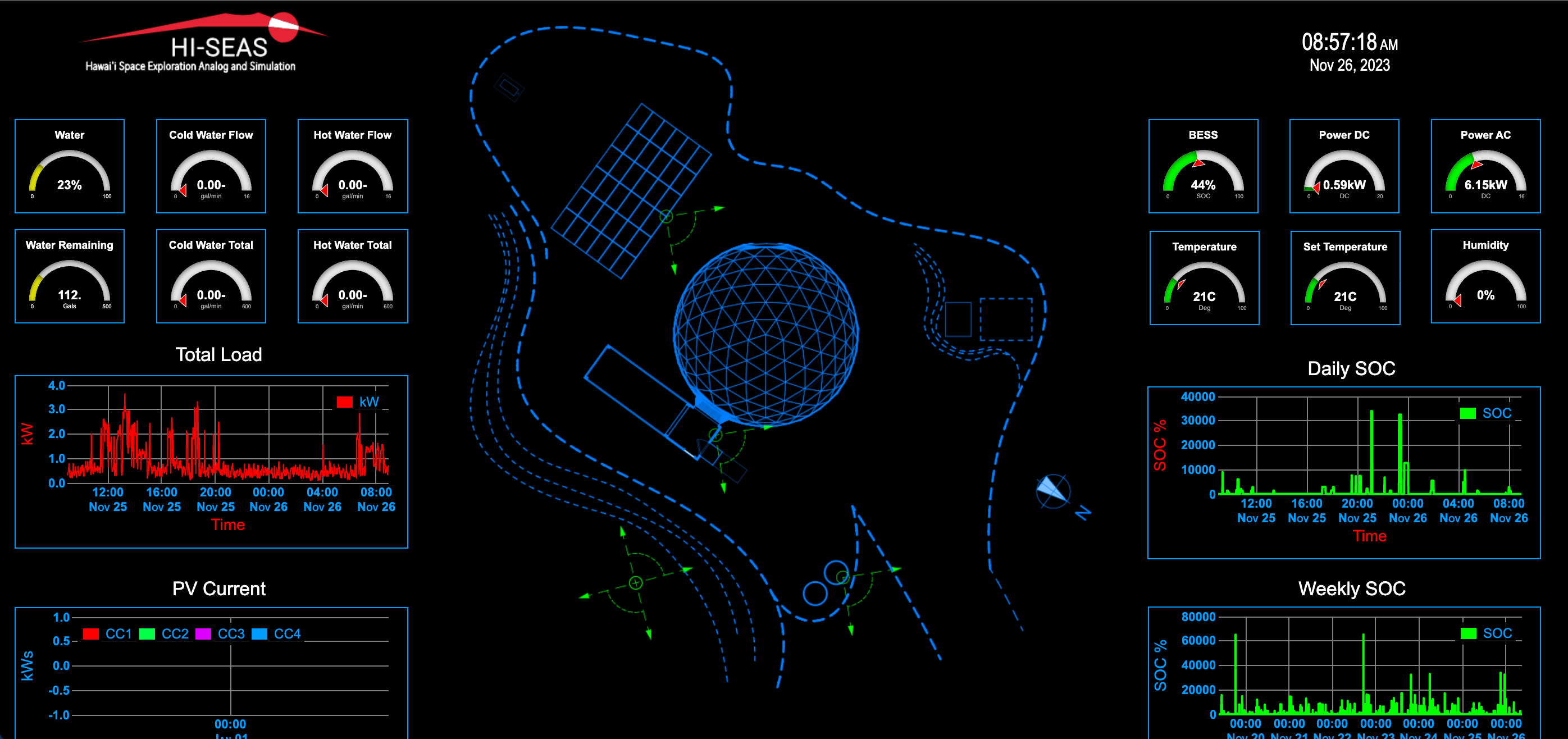

“Habitat for the Human Animal,” which opened in Downtown LA in October, was born from Fiorentino’s experiences during a five-day mission to the HI-SEAS Mars simulator atop Mauna Loa on the island of Hawaii. Selected for the mission as part of a cohort of five researchers, Fiorentino’s own research, which is uniquely positioned at the intersection of the social, the psychic, and contemporary aesthetics, considered what the necessary conditions were for the survival and well-being of humans on long interplanetary space journeys. Within just five days—a day less than it takes to travel to the moon and back, and microscopic in comparison to the nine months it takes to reach Mars—isolation collapsed in on Fiorentino. The implementation of various simulated controls, including a 20-minute delay in external communications, led Fiorentino to feel divorced from culture.

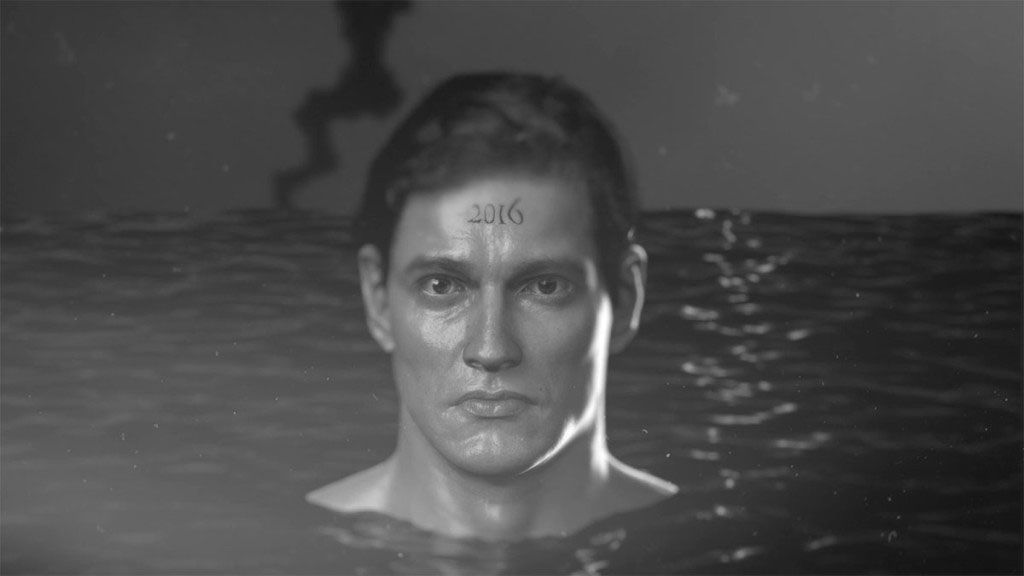

Equally contending with the question of whether social mores will remain once most other markers of culture are removed, Fiorentino developed a relationship with his camera in isolation. The result was a series of timed self-portraits captured in the HI-SEAS geodesic dome’s airlock zone. Fiorentino, whose face is somewhat obscured by the black balaclava he wears, presents himself in blurry depictions of erratic movement, gesturing toward the burgeoning anguish that the experience produced. From this image base, Fiorentino produced more images, still and moving. Fiorentino portrays himself walking amidst the rocky, arid Mars-like landscape atop Mauna Loa. He captures himself from behind, as if to suggest nature’s violent indifference, shrouded as if to imply the importance of self-protection, and from above as if to illustrate the insignificance of a lone human in environments of such scale. In these images, along with the spectral short film set to the music of BFRND that he activated with an accompanying performance at the opening, Fiorentino ultimately pictures himself as a future space settler, cleaved from his home and the idea that space travel is somehow a romantic or exceptionally heroic feat. In this, “Habitat” functions as an intervention in a long lineage of misleading, or at least limited, ideas around space travel—an intervention as aesthetic as it is discursive. The key themes that emerged from Fiorentino’s experience at HI-SEAS—psychological toil, extreme isolation, masculine glamour, and American exceptionalism—do not exist independent from one another, but in fact form the crux of the matter: Space travel is not what it’s made out to be.

HI-SEAS (Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation) simulation photography courtesy of Ryan Fiorentino

Following the opening of “Habitat for the Human Animal,” I sat down with Fiorentino to discuss the relationship between his research for NASA’s JPL and his independent art practice.

PHILLIP PYLE: This project was born on a simulation mission you did at HI-SEAS. Can you talk a bit about how you became familiar with HI-SEAS and the specifics of the mission?

RYAN FIORENTINO: Probably eight years ago, I built a relationship with Diane McGrath, an Australian who was in the candidate selection pool for what is now a defunct organization that was trying to down select from 200,000 applicants to a small group of 100. She was in the final 100 for future Mars settlers. I wasn’t involved with NASA at that point, and I was just curious about what the hell that was going to mean. I reached out, and we started going back and forth. I was curious about her, what she was going through, and where she came from, and why she thought she wanted to do it at all. I started a bit of an ethnography with her life and story. We got into some shared readings together and started to get curious about what this meant to reboot humanity, what the cultural precursors were to human interstellar migration. What’s going to happen with self-agency? What would be the reinforcing mechanisms in a new culture for people to understand whether they’re operating in responsible and respectful manners? Where’s the sacred in all of this? What are the necessary human enclosures for flourishing as we start to go beyond? HI-SEAS was really on her recommendation.

That is some of the origin story to how, years and years later, I ended up at NASA. I was doing the White House Presidential Innovation Fellowship for a period of years, supporting NASA senior leadership, and that’s how I found my way to NASA JPL. But the curiosity came from way back then, and then I finally had the opportunity to embark on one of these missions at HI-SEAS. I took on the role of vice commander in a small cohort of five. HI-SEAS is an amazing place. It’s 8,200 feet above sea level on a volcano. It’s been the home to many domestic space agency, NASA, and International Space Agency missions anywhere from short duration to multi-month or yearlong missions. The habitat itself is 13,000 cubic feet and 1,200 square feet of living space. You’re in a geodesic dome with an air lock and livable quarters for a small group of people. It’s resource constrained in an interesting way, so if there isn’t a hammer for the nail you need to punch in, you got to figure something else out. I had the freedom and flexibility to do self-directed research. There was a protocol to the day, which is extremely scripted and rigid. Some of that involved independent mission-specific tasking, like for periods of the day, it would be one individual’s responsibility to ensure that the safety systems were up and running effectively. Another would be food prep. Another would be equipment safety checks.

When I say we were in a volcano, we were in lava fields, miles from a road. You weren’t walking out of this thing. We did deep cave diving, where there’d be a lookout, and two of you would go down with headlamps an hour hike deep into a lava tube and try to perform some complex problem-solving exercise while they would be attempting to be on relay to the lookout and home base. Individuals would look at where the human system breaks under periods of extreme stress. There’d be audibles inside there, like: “Something’s broken, you now have 45 minutes of oxygen left and you’re two hours away from home. Figure out how you’re going to get back.” My exercise was to take witness to what that human experience was in the context of that place. What was going to happen in terms of a group dynamic, what happens when you’re completely disconnected and severed from your culture and your community? Is culture going to hold in place? I didn’t take it as far theatrically as I could have—like I was really curious to paint my face one morning and come downstairs and see what the fuck happened.

PP: I read that outside communication takes 20 minutes to reach the simulator. Did that make you feel literally out of line with humanity?

RF: Certainly. Everything that has been built today, such as the International Space Station, is also a very sterile environment with very specific humans involved. There are series of fundamental human needs that in an institutional sterile environment aren’t accommodated for because they take a lot of space. Even in this conversation, I’m a little distracted because this incense is burning heavy. It’s in my head and I’m a little tired from a couple days ago. There’s no room for that thinking in the rigidity of the manufactured space environment.

Photography courtesy of Ryan Fiorentino

PP: The work doesn’t read as super humanist to me, but you are using the term “human” a lot or foregrounding the needs of humans a lot.

RF: It’s totally a humanist project. I think the themes of emotional and societal dismemberment bear a striking resemblance to terrestrial issues proliferating today. Deep space is used as a tool for considering the preciousness of our innate human fabric, and a mirror reflecting back new perspective of our societal interior. The humanist part of it is intending to portray a truth so we can take stock of the opportunity and beauty that we have here and understand how to respect each other more. It’s important for us to be here. This is a conversation that is fundamental to the core of our existence. We’re entering a time where we’re at a technological inflection and at a climate inflection. 1,000 years from now, they will look back at this moment in time and see rapid evolution, and it’s on us to figure out how we want to author that future—and what is needed to be most constructive is that a wide and diverse array of cultural interpreters and creative practitioners are invited to engage with that. I think that this dialogue has been very top down, centralized in many cases—not just from the West—politically motivated, and technologically and culturally somewhat hard to access. I think part of the intention is to ask questions like: Are we ready? Should we go? Who should be talking about this? The intention is to equip people with an opportunity to engage with the content with a little bit more fluency. That is the role of the aesthetic intervention.

PP: The speculative element is interesting to me because it seems that you’re also contending with the fact that what it means to be human is changing and that a post-human state is emerging.

RF: My work both independently and at NASA is primarily focused on things that are chapters ahead. If you were working at Apple on the next version of iOS, you’re working three, five, six months ahead. At NASA, a normal mission could not be set to fly for a decade plus, using technology that isn’t even created yet. That’s the normal day to day, so when you’re thinking about trying to get in front of that, you are talking about plus 50 years, or you could be talking about something that can’t be built for another 25 years and that takes 50 years to get to the place where it’s set to go. So, we’re talking about plus 100 years, plus 500 years. In those eras, the use of science fiction prototyping becomes a fair craft, like using narrative to explore the boundary conditions of multiple scenarios colliding. There is no such thing as predicting, as breaking the future. There’s just exploring, with the application of narrative, different paths that you could intertwine with other paths, and trying to imagine what the implications are of two things colliding.

Also, a lot of my creative work has to do with legacy. With the current media landscape, there is a temporal dynamic that makes every little piece of content immediately exhausted. Its half-life is three seconds. Also, the volume of touch points is such that someone who has global attention actually has the opportunity to embody a cultural thread in a way that didn’t exist 100 years ago. A lot of the work I do is helping build legacy to some of those cultural threads and help them extend beyond their origin because I think they’re important. In the case of “Habitat,” I think the legacy question is “humans,” is “us.” Many of the questions the work prompts are not so much about out there as they are about right here. It’s a call to action in many ways for us to take stock of the specialness of human connection, to share an understanding of what it means to be human.

PP: There’s no shortage of left-field sci-fi depictions of space in art and literature, but because you’re uniquely positioned between science and art, this work has a unique crossover ability—and I imagine it’s rarer to find left-field depictions in your field. Have your peers been receptive to this “aesthetic intervention”?

RF: There have been a lot of technological firsts and scientific firsts that have been achieved in Pasadena at the JPL. You’re around the world’s leading in you name it, so everyone’s kind of able to be themselves. Inside my community, there is an opportunity for people to sit more in the seam between different contexts and invite others into a conversation. The institution itself has its own language of creative expression, and I think that it might be among the most prolific creative studios in human history. I am a practitioner in that container. I’m also a practitioner on my own. What it feels like on my own is embracing a sense of freedom to say what I want that is unencumbered and representing points of view that speak to my community in ways that are unfiltered.

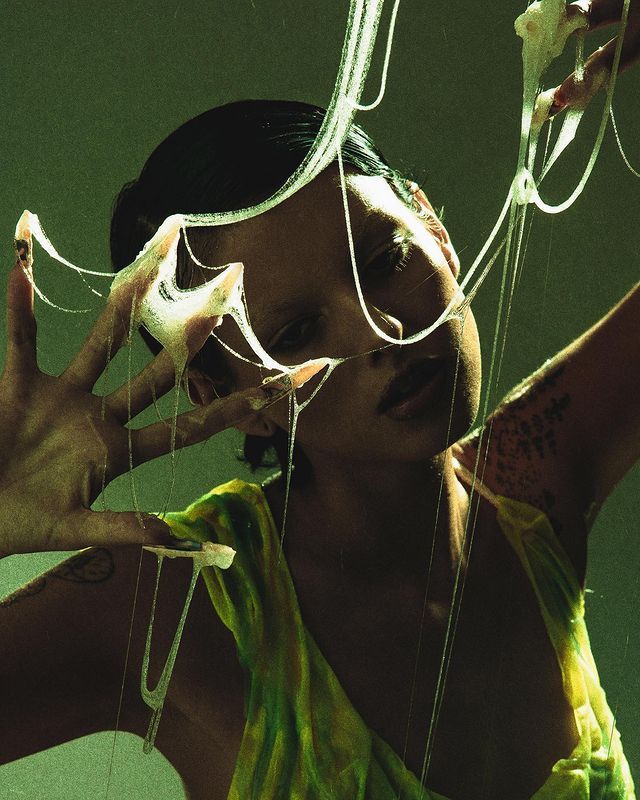

Photography courtesy of Ryan Fiorentino

PP: I want to talk a little bit about the performance element of the work, which felt like an activation in a way. Could you talk about the process behind the performance, and the choreography, in particular? It looked similar to the movements in the self-portraits.

RF: I worked with this profound production designer Tiger George and a special up-and-coming film editor Jean Hsi. The intent was to invite the audience into a world through film, lighting, soundscape, body movement, and stage design that both evoked a sacred atmosphere and explored these big thematic questions: “Is it home? Is it prison? Am I effectively contained in this space, physically, emotionally, spiritually? Are we in crisis? If I yell, who is listening?” Just as spacesuits and enclosure are designed with the survival of an organism in mind, this project asks: What are the social, psychological, and emotional enclosures necessary for the human animal to flourish, on Earth or beyond it?

Inside the portraits, compulsion and repetition emerged reflecting this sort of Freudian death drive. They were composed, these movements specifically, with a still camera on two to five second bursts, absolutely unscripted. I would escape, get away from the group, and go in the air lock zone where we had a little tool room just to get some privacy. There was certainly a direct reference between the self-portraits and film from the simulation and the exhibition performance, which combine to be the hero content from “Habitat.”

I have some folks in my community that I look up to creatively, like Tom Heyes [Blackhaine]. My interpretation of what he’s channeling, and why it’s so resonant, is that it’s so true. In both the stills and performance, I can see a choreographic reference to that Japanese Butoh, empty body flow that he’s [Heyes] on. I think that frequency is very appropriate to the time we are in. I don’t proclaim to be trained in it and wasn’t necessarily trying to do something scripted. It was just in my sphere as I embarked on this all.

Also, I want to note there are a few people that this thing would not exist without, certainly my research partner Dr. Lois Rosson, my executive producer Hector Harold, co-executive producer Jordan Rondel, and the folks at The Showroom.

PP: During your discussion with Lois, you both talked about nationalism as a key part of past depictions of space travel in visual culture. This project though attempts to envision the psychology of the space traveler devoid of a nation state. If an individual chooses to embark on space travel for the purpose of private industry, knowing that it might not even result in anything, I’m wondering what the psychology of that is?

RF: You use the word “choose.” Maybe! I don’t know if you saw the Trump post recently where Elon came onto stage wearing an "Occupy Mars" shirt. These words, "occupy" and "colonize," prompt the question: Are the first people going over there the colonizers? Or are the first people going over there being colonized by choice by this colonizing apparatus? There are questions of where the power is held, and what are you signing up for. For instance, do we get to choose, if we go there as a male and a female couple in a relationship, to have children, or is it dictated to us? I think, to actively achieve the first few cycles of human expansion, this thing is going to be predicated on a lot of dictatorial ideas.

So, who should be dictating that? Right now, there’s some version of a hybrid nation state-private industry model. That’s changing, and who knows where that’s going to be when we actually start setting up. If I were to design the committee, it would be a cross section of elders of humanity. We also could do this right now and fuck it up hard, then find ourselves disenfranchised because we weren’t ready and have to start this all over again 1,500 years from now. We have the opportunity technologically to start this, but we, culturally, aren’t really mobilized to not take our human problems with us yet.

Conclusion

During Dr. Lois Rosson’s conversation with Fiorentino at the opening of “Habitat for the Human Animal,” Rosson described space as functioning like a “human Rorschach test.” The internet works in this way, too, reflecting our selves back to ourselves in ways as recognizable as they are estranged, in a presentation not unlike the eternal self-alienation of Lacan’s mirror stage. In this psychological perversion, the solution to the internet’s issues are presented not only as a hardware problem but also a “software problem,” a term that Fiorentino uses to describe the human-shaped holes within dominant narratives around contemporary space travel.

As a parallel to the intervening internet aesthetics raised by artists such as Jon Rafman, Jordan Wolfson, and Andrew Norman Wilson, whose work emerges from the internet's technological and psychological nexus, Fiorentino’s speculative, scientifically-grounded practice alights the Earthly isolation and alienation from which the very urge to colonize another planet springs in the first place. With the dawn of interplanetary space travel purportedly nearer and nearer and the colonially laden visual and linguistic schemas still ever present in discussions around space, it’s been high time for such interference. That “Habitat” was informed by Fiorentino’s work within an official center of research and discourse, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, only makes its findings more acute. In this Post-Space X work, Fiorentino ultimately reverses the central question undergirding contemporary space research, asking “What if the frontiers that we should be exploring are what it means to flourish in this environment?”

Credits

- Text: PHILLIP PYLE

Related Content

All Networks Lead Through Kansas: The Shadowy Well(ness) of Masculinity

All Networks Lead Through Kansas: The Text Image

Mire Lee’s Fountain of Filth

“We Cannot Assume False Neutrality”: Wu Ming—from the Luther Blissett community

Bryan Johnson: “Death is a Technical Problem”

Where Does The Puppet End And The Human Begin?

Nothing is Linear: Guy Trebay

MATTHEW BARNEY: Ancient Evenings

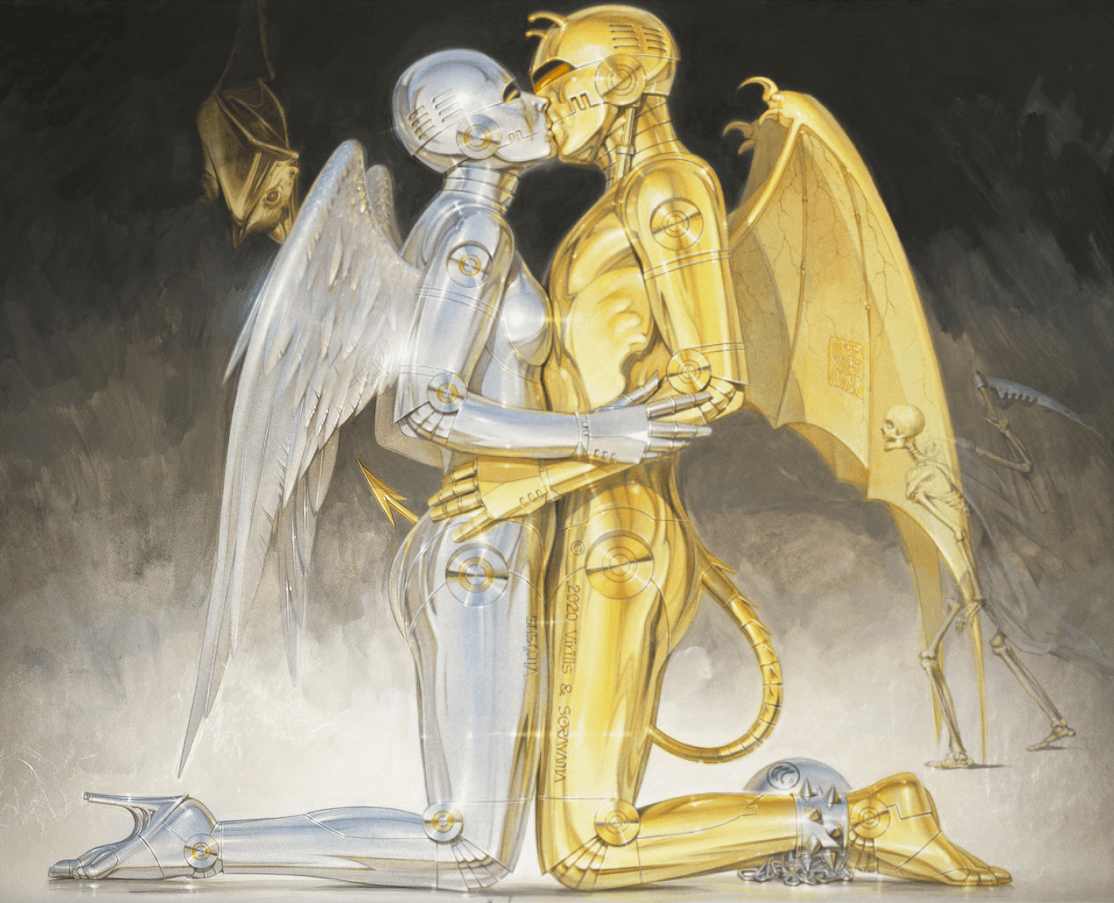

Hajime Sorayama: What I Draw Are Human Beings

An Orgy of the Mind With Charlie Fox

Notes From Underground: Slime Fetish

Digital Alchemies Resurrect the Dead