Where Does The Puppet End And The Human Begin?

|GÜNSELI YALCINKAYA

Lately, I’ve been seeing puppets everywhere.

“This is a cybernetic folktale that illustrates our relationship to life and death, of material and immaterial worlds,” writes GÜNSELI YALCINKAYA. Through DM strings with Freeka Tet, Maison Margiela’s widely circulated AW-24, Shoggoth memes of artificial intelligence, and more, Yalcinkaya disseminates our innate kinship towards the puppet and its return as today’s folkloric symbol.

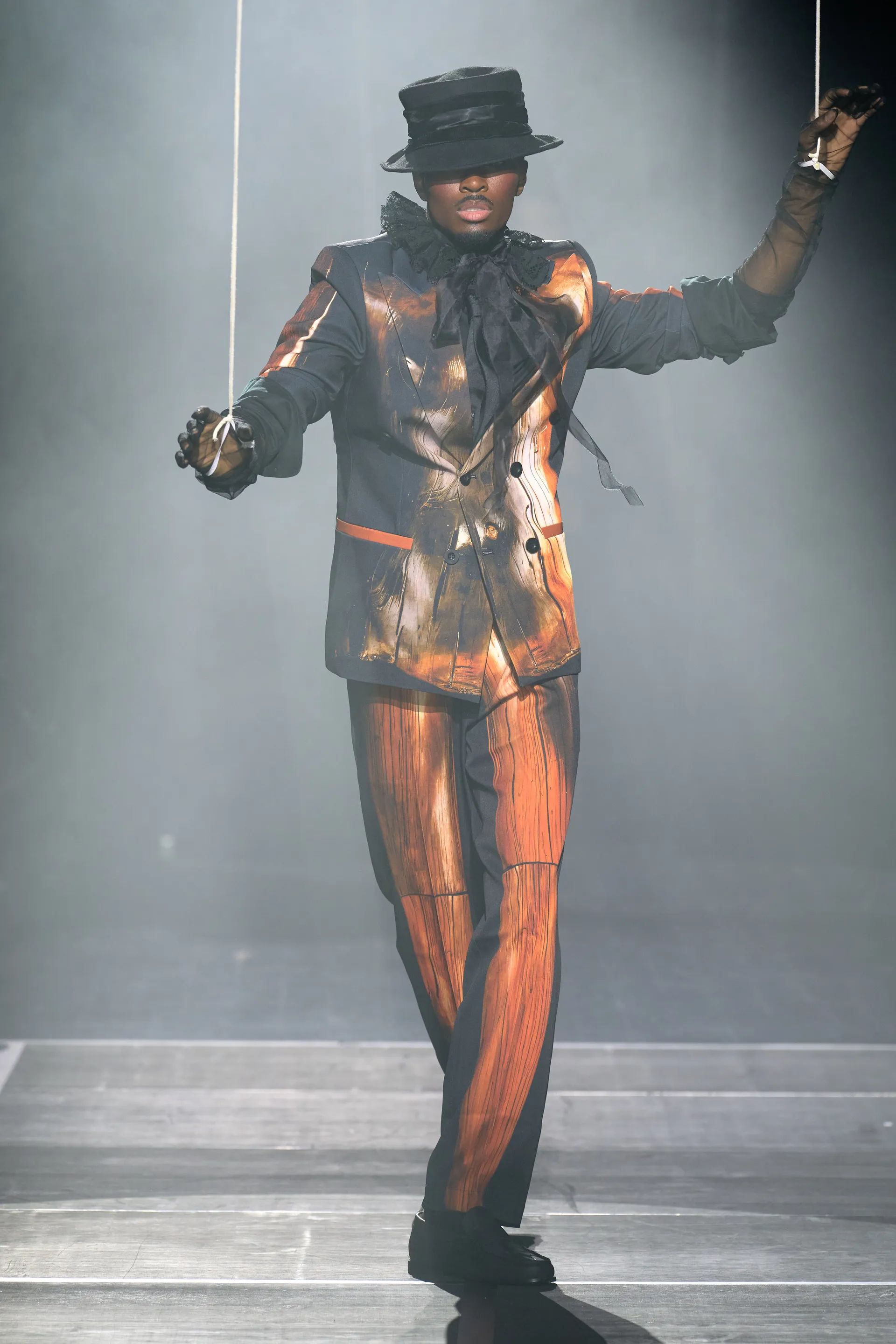

It began earlier this year with Maison Margiela’s widely circulated AW-24 couture show, with real models reimagined as jointed marionettes tottering down the runway. Then it was Mau Morgo’s Chris Cunningham-inspired music video for Brutalismus 3000’s “Europatraume,” featuring a shadowy puppet pulling the strings of real human actors. And then it was Freeka Tet’s real-time puppet show for Oneohtrix Point Never’s nostalgic Again tour.

The interest in puppets comes with recent advancements in artificial intelligence, where the onrush of chatbots and text-to-image generators is driving overstimulated users back to simpler, more analogue times.

“We’re entering a ‘hate technology’ cycle,” Freeka Tet tells me in a DM. “People are worried about creativity with AI and need to go back to some type of craftsmanship. Our entire system is based on hauntology, and the current relationship between puppets and the present world is a perfect representation of that.”

In OPN’s show, an accurate scale model of a rod-operated Daniel Lopatin is live-streamed onto the big screen. During an interval, a large rubber hand, cartoonish is appearance and size, removes the puppet’s head and replaces it with that of a gas mask, highlighting the puppet’s absurd power in softening what could be seen as sinister—like that of the happily murderous Mister Punch or Carlo Collodi’s trickster Pinocchio.

There’s also a magical quality to puppets that allows us to reflect on our relationship to the unknown—a tool of ritual magic used to embody spirits and ghosts, or a mysterious double to channel our innermost fantasies. KidSuper’s AW-24 show entitled “String Theory” was inspired by the ways we’re all connected to each other across multiple dimensions, while SS-25 saw models dressed as wooden puppets spotlit under an enormous prop hand from which marionette strings fell onto the runway. The innocence of the puppet keeps the imagination open to all kinds of unearthly forces—be that the angelic figures of Paul Klee’s hand puppets or Jordan Wolfson’s animatronic sculptures that make us question the relationship between human and non-human things—or as he puts it, “seeing ourselves through three‑dimensional objects.”

Somewhere in between all this, I believe, lies the return of the puppet as a folkloric symbol.

At once sinister and playful, puppets are uncanny things brought to life through the freaky communion between a human and an object. It’s this paradoxical nature of an inanimate object that is also imagined to be alive—while remaining dead—that makes the puppet so unsettling. They are frequently parodies of the human figure, controlled via strings or rods, which create a dissonance in the not-quite-human-ness of it all. This is perhaps why puppets or dolls are usually associated with cyborgs—such as in Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast (2023). They exist as a hybrid category both real and artificial. Yet it’s the interdependence between man and puppet that makes them so mesmerizing to watch. In Margiela’s FW-98 collection, a cast of marionettes wrapped in plastic on a Parisian runway are maneuvered down the stage by men in lab coats.

Half suspended in a hall of mirrors between the real world and the imaginary, the question to keep in mind is: where does the puppet end and the human begin?

In the prelude to her book Raving (2023), McKenzie Wark draws on Heinrich von Kleist’s On the Marionette Theatre to pinpoint what’s so magical about puppets, describing them as the “symbol of ideal human nature.” The puppet, unlike a human, isn’t conscious, it can only come alive when the puppeteer has entered a subconscious state not too dissimilar to Wark’s cathartic description of rave space as feeling “free of selfhood.” It’s exactly this liminal state of being—between the conscious and unconscious, the self and other—that occurs as virtual and material worlds become inseparable, whole identities can be built that operate with the same dual nature of a puppet, whereby human behavior is driven by the machine—through platform physics that incentivizes certain types of content over others, such as thirst traps over text blocks, and mimetic gestures that are replicated, remixed, disseminated and passed down the eternal scroll.

Admittedly, the nostalgia associated with puppets throws back to some of our earliest childhood memories—or as Freeka Tet puts it, “Who hasn’t seen a puppet show at some point in their childhood?” The puppet’s tactility is a pure contrast to the smoothness of the network. They pass the vibe check, which might explain why we feel such kinship towards them.

Predicting our collective spiral down the puppet paradigm in 1970, Finnish philosopher Erkki Kurenniemi stated: “Our true descendants will be algorithms.” Nowadays, our online behavior is quantified by clicks and likes; it resembles an AI text-to-image prompt, with algorithm-friendly repetition that recalls the movements of a marionette. Having spent much of his career tracing the impact of new technologies on human evolution, Kurenniemi made a distinction between the hardware (body) and software (soul), writing that “software can be somewhat immortal” because it exists outside of space-time. This says something deeper about ourselves—it’s traditionally believed that the puppet plays a particular role in helping us to question our relationship to death, whereby humans must learn to become a puppet, to give up being a subject, and therefore become a “thing.” This process of becoming-thing is particularly useful when navigating virtual spaces—the internet is as eternal as it is ephemeral, which is probably why Big Tech is so obsessed with concepts such as digital immortality.

To exist in this vibey soup of a simulation, what K Allado-McDowell has theorized as “neural media,” is to mold our behavior to best fit the machine, to turn ourselves into a puppet if you will.

Yet anyone on social media who’s spent time building an online persona can understand the suspension of disbelief necessary for any virtual interaction.

There’s a seismic gap between our meat bodies and the fantasies we project on-screen, fragmented across various avatars, face filters, memes, and Facetuned selfies.

“What if [the extreme self] is the only version of you that matters anymore?” ask authors Shumon Basar, Douglas Coupland, and Hans Ulrich Obrist in The Extreme Self (2021), hinting at how our identities are shaped by the simulation, which makes the simulation feel more real than reality itself. In truth, it’s not too dissimilar to how a puppeteer might select the wood, cloth, and paints to build his marionette. On-screen our identities are carefully curated versions of ourselves that have little resemblance to our “real” selves, yet it’s these digital representations that carry off-screen and into the “real” world—when we watch a puppet show we’re equally buying into the illusion that the puppet is alive because their actions imitate our own. The changing backdrops of the marionette theater offer yet another useful metaphor for the disorientating shift in realities we experience when switching tabs or moving between platforms—“how the background too, like the static puppet, is just another character in the story,” suggests Italian philosopher Federico Campagna in Technic and Magic.

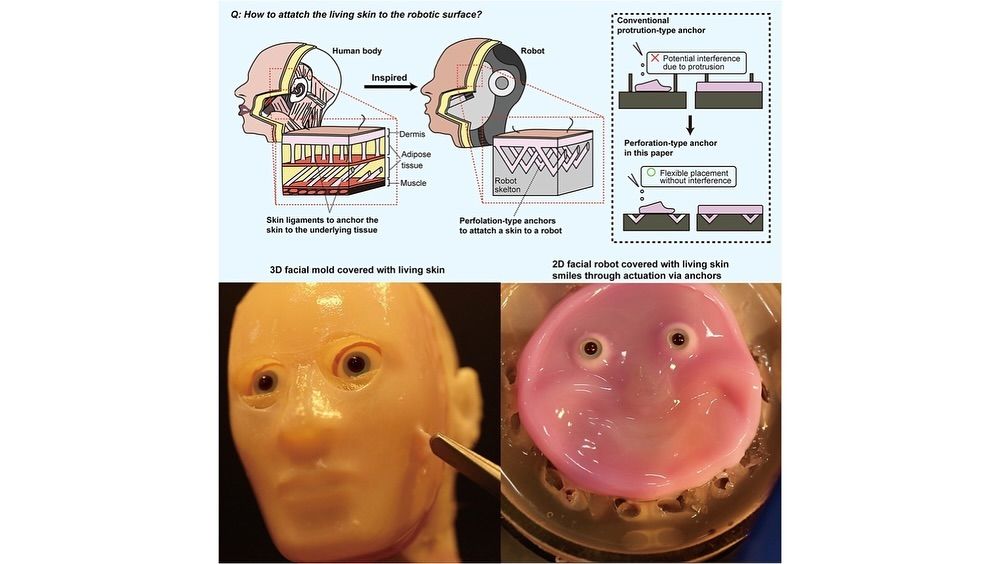

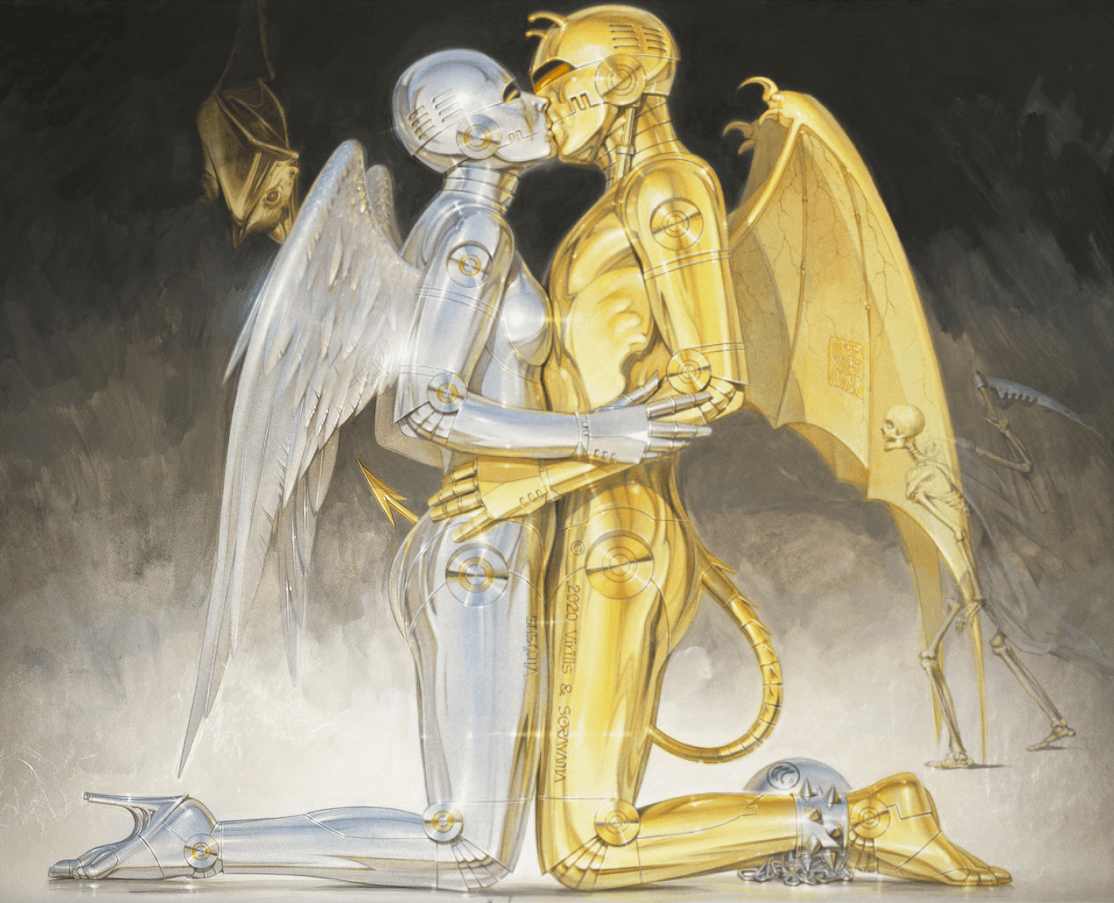

Cyborgs, in contrast, feel unnatural as a most basic human impulse—this is presumably why Masahiro Mori in his original Uncanny Valley diagram describes the bunraku puppet as an object with a human appearance that overcomes the “uncanny” feelings triggered by robots, instead invoking a deep emotional response in the subject. As technology advances, through the mainstreaming of AI and robots, the gap between man and machine is deteriorating—ChatGPT4 passed the Turing test earlier this year, meaning that it’s indistinguishable from a human. This past week, an advert for a humanoid robot called NEO Beta is making the rounds on socials; and it is predicted to go onto market later this year. The Instagram account @the_political_compass posts a meme that juxtaposes the news with another viral headline that claims “women will be having more sex with ROBOTS than men by 2025.” The caption reads, “17 weeks.” It reminds me of another clip of a freaky robot with lab-grown skin that circulated the feed a few months back as part of an ongoing research project at Harvard University. The Shoggoth meme of AI with a cute “human” mask further points at our eagerness to anthropomorphize this non-human intelligence—chatbots, therapy bots, service bots, and sex bots that are programmed to successfully mimic human behavior, much like Mori’s description of the bunraku puppet.

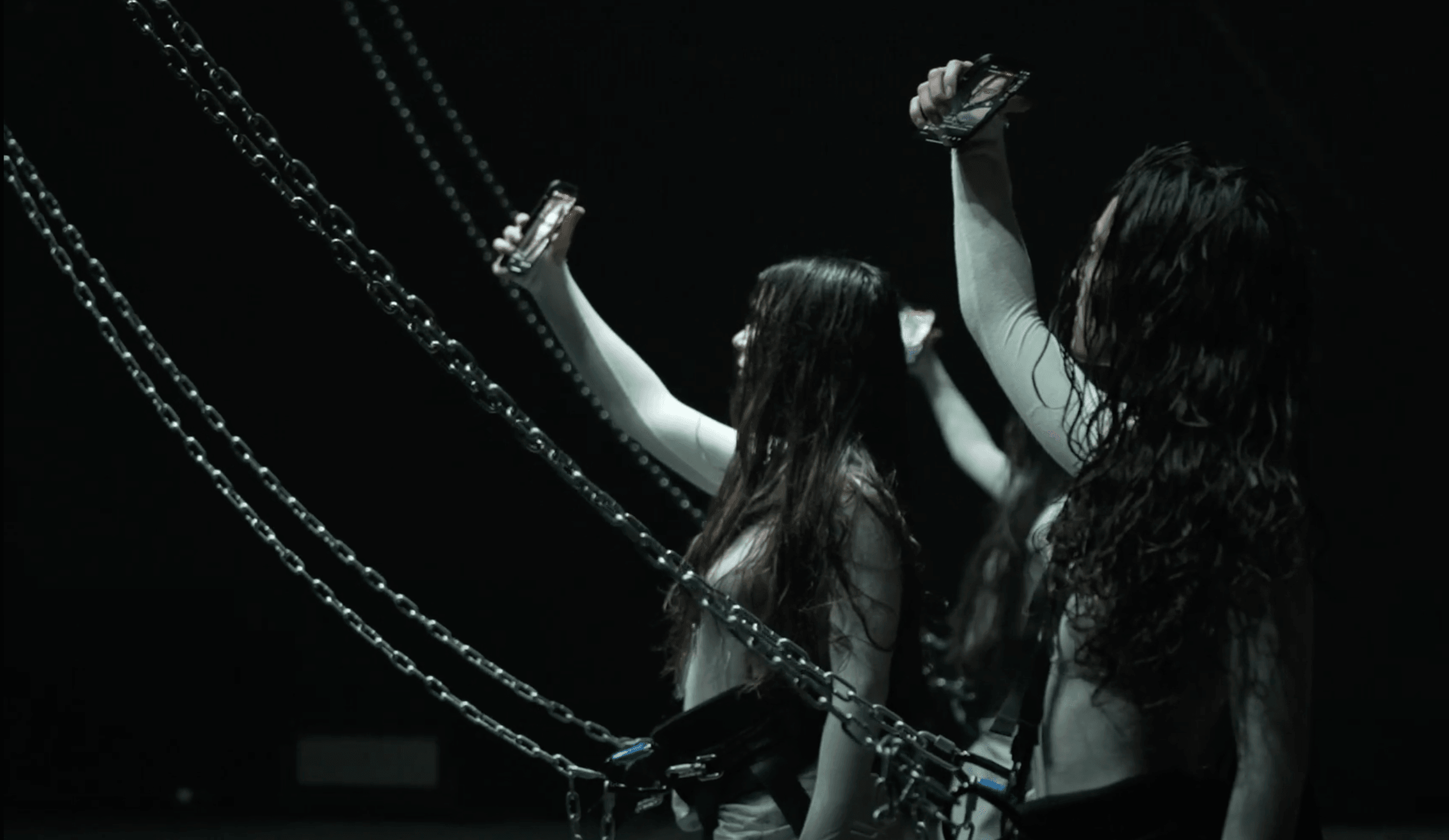

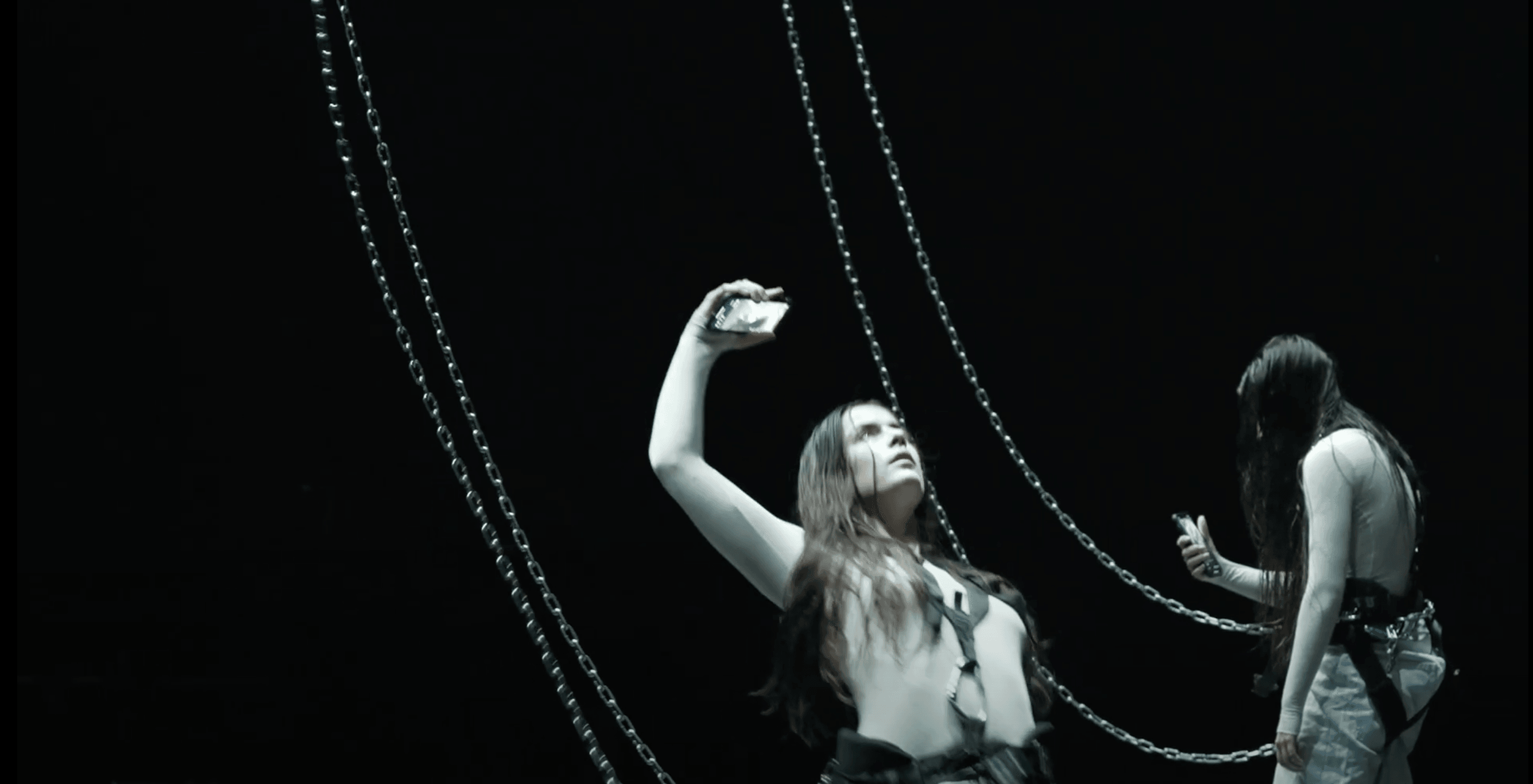

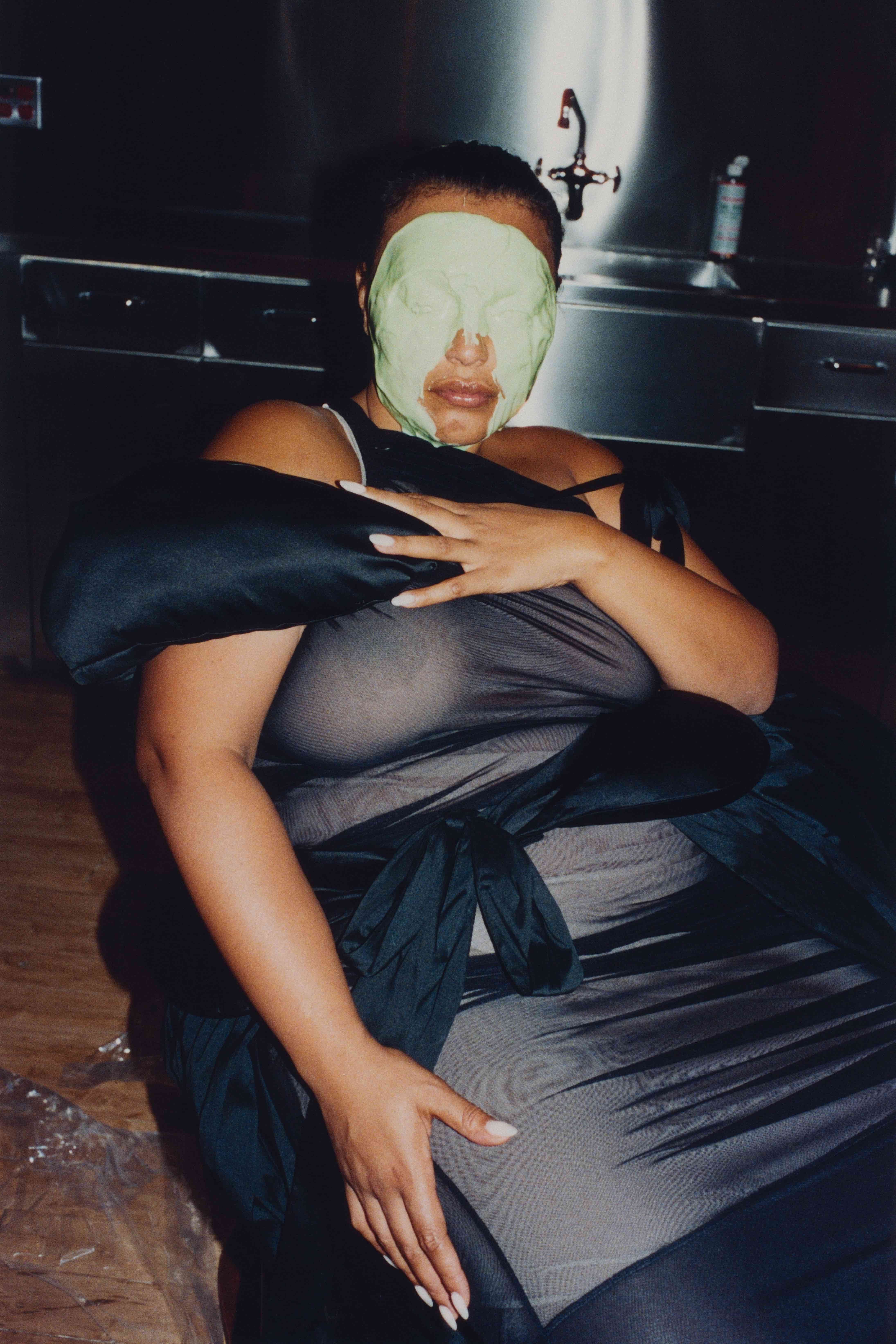

This cybernetic theme permeates the work of Spanish choreographer Candela Capitán, whose Models (2023)—in collaboration with Hyperdub’s Lee Gamble—features a group of dancers literally chained to their devices, live-streaming the entire performance on TikTok. In Capitán’s follow-up work, Solas (2023), dancers face crotch to camera, twerking endlessly in repetitive motions in what is meant to signify the crossing of bodies from a stage onto the screen. “Solas exhibits the copying, repetition and the wear and tear of the image on the internet,” writes Capitán. “It also highlights the hyper-individualism and hyper-connectivity present across social networks.” Whether nudging us to perform for the feed or participating in the endless sharing of images online, these algorithmic forces direct our behavior like a puppeteer controls a puppet. The strings might not always be visible, but they pull us away from the “real” world of flesh and bones, and into a freaky funhouse of static images, of vibes of things.

It’s an ironic twist that the puppets are becoming more human-like, while we humans are beginning to resemble puppets.

This is a cybernetic folktale that illustrates our relationship to life and death, of material and immaterial worlds. But we mustn’t forget the machine is a trickster who’s ability to pull at our heart strings and convince us of its humanity is well-proven—Pinocchio wants to grow up to become a real boy, but he’s also a liar.

This says more about our own imagination—who’s pulling the strings? To look past the hypertext is to expose the hybrid at its core.

Credits

- Text: GÜNSELI YALCINKAYA

Related Content

CHILD’S PLAY

An Album is a Tragedy: AMNESIA SCANNER & FREEKA TET

All Networks Lead Through Kansas: The Text Image

Hajime Sorayama: What I Draw Are Human Beings

What Future Do We Crave?: KATHARINA KORBJUHN’s Paradigm Trilogy

Love in the Time of Prompting: SHUMON BASAR and Y7’s CORE+LORE

KRISTINA NAGEL’s Landscapes of Depersonalizations

Despair and Dystopia Next Door: ART SPIEGELMAN in conversation with HANS ULRICH OBRIST

The Future of Couture: Neo-digital natives, blockchain luxury, and algorithmic customization

Notes From Underground: LUKE NUGENT’s AI Editorials Fictionalize Subcultures

Why Not End It Here, Right Now: HIDEO KOJIMA

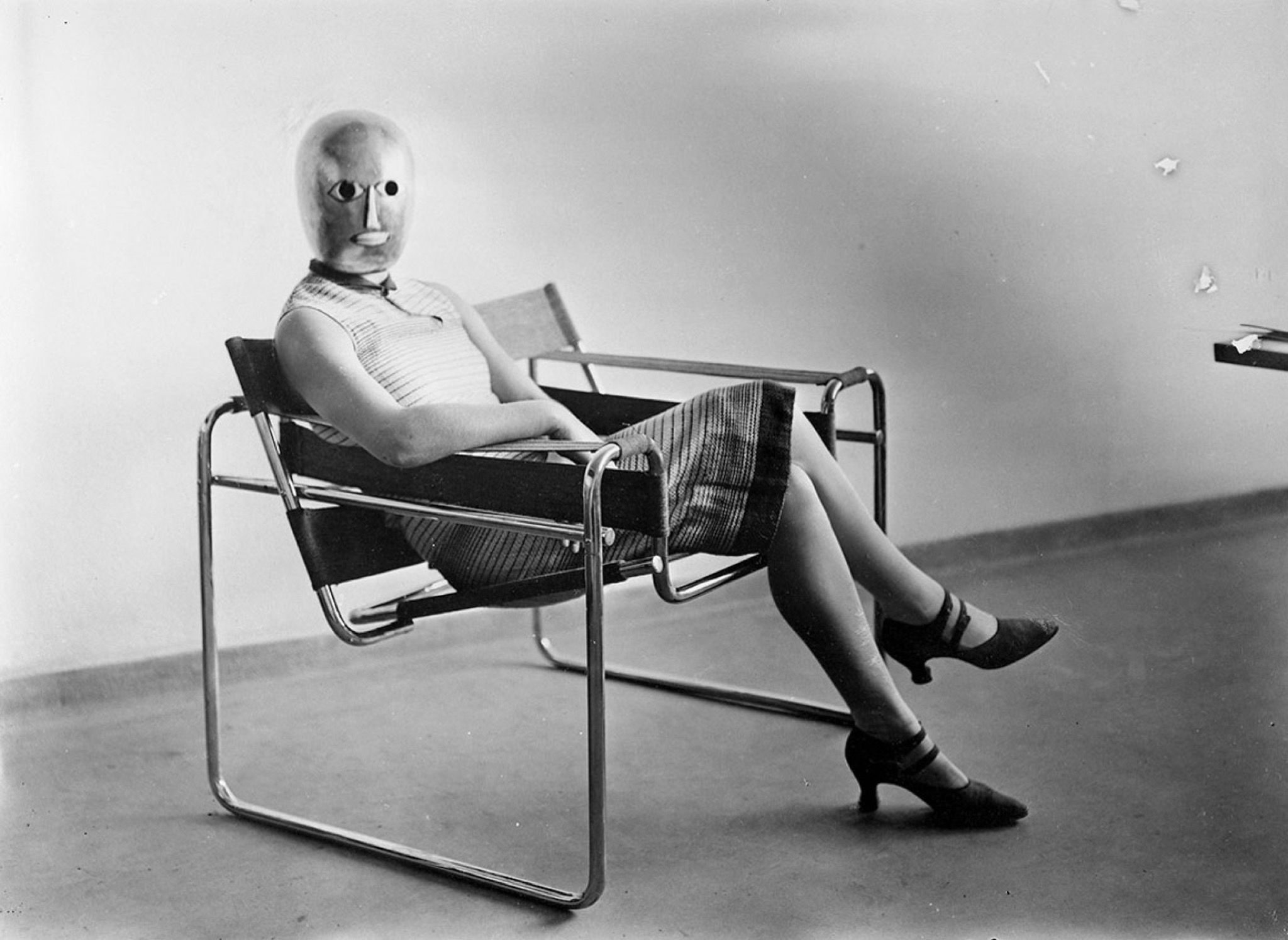

BAUHAUS 100: Eulogy for a Perversion