“We Cannot Assume False Neutrality”: Wu Ming—from the Luther Blissett community

|AGNES MAGGIE SHU

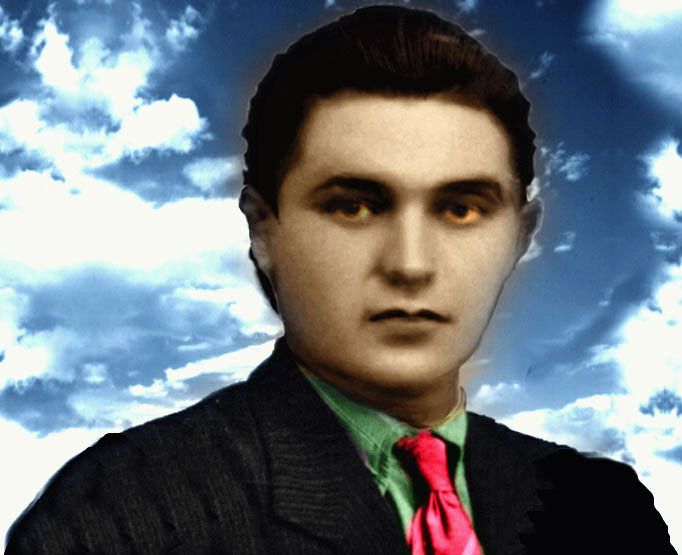

The photographic portrait of the imaginary "Luther Blissett", made with digital techniques in 1994 and used as a symbol of the homonymous project and set of collectives.

In 1996, spray paint of satanic characters inexplicably appeared on an abandoned farmhouse outside Viterbo, Italy. National press jumped to cover the graffiti and mass paranoia ensued to discover its origins. Neo-Nazi groups, black magic? It was only when the elusive activist figure Luther Blissett claimed responsibility that the events were exposed as a sham.

It was a mockery of mass media. A prank executed at the highest level. Praised and analyzed by scholars and media experts, the event became a case study on the lack of due diligence that had become normalized in the information age; the speed at which misinformation can be spread.

Lifted from the British-Jamaican footballer of the same name for reasons unknown, the project “Luther Blissett” thrived on pranks, radical performance art, and guerrilla communication. Originating as a group of social activists and artists from Bologna with global compatriots, the Luther Blissett Project soon developed into an international movement—one with no central company, where anyone could become “Luther Blissett” simply by adopting the name. But on the first day of the new millennium, “Luther Blissett” committed seppuku.

It marked the finale of the Luther Blissett Project’s Five Year Plan, the movement having been active since 1994. The act of ritual suicide did not entail the end of the name—it still remains a popular byline. In 2007, a new generation of Luther Blissetts played another prank, this time preceding the release of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. But it was a catalyst for the veterans of the project to evolve. “Become Luther Blissett, and I'll become someone else.” And so, they did.

Before the seppuku of “Luther Blissett,” five veterans of the project had authored what is now known as the best-selling novel Q under the pseudonym. It was in anticipation of their next move: their resurrection as “Wu Ming”—a smaller, more concentrated collective, one that furthered their ambitions while specializing in the literary field. The publication of their identities is another development in their practice, like claiming responsibility for their prank back in Viterbo. “It’s a strategy we get from magicians,” Wu Ming 4 tells me. “The explanation of the trick is another trick in of itself.” Each of the five were named Wu Ming and numbered according to the alphabetical order of their surname. It was a democratic approach: Roberto Bui became Wu Ming 1; Giovanni Cattabriga, Wu Ming 2; Luca Di Meo, Wu Ming 3; Federico Guglielmi, Wu Ming 4; and Riccardo Pedrini, Wu Ming 5. Now, only three of the five remain in the writers’ collective: Wu Ming 1, 2, and 4.

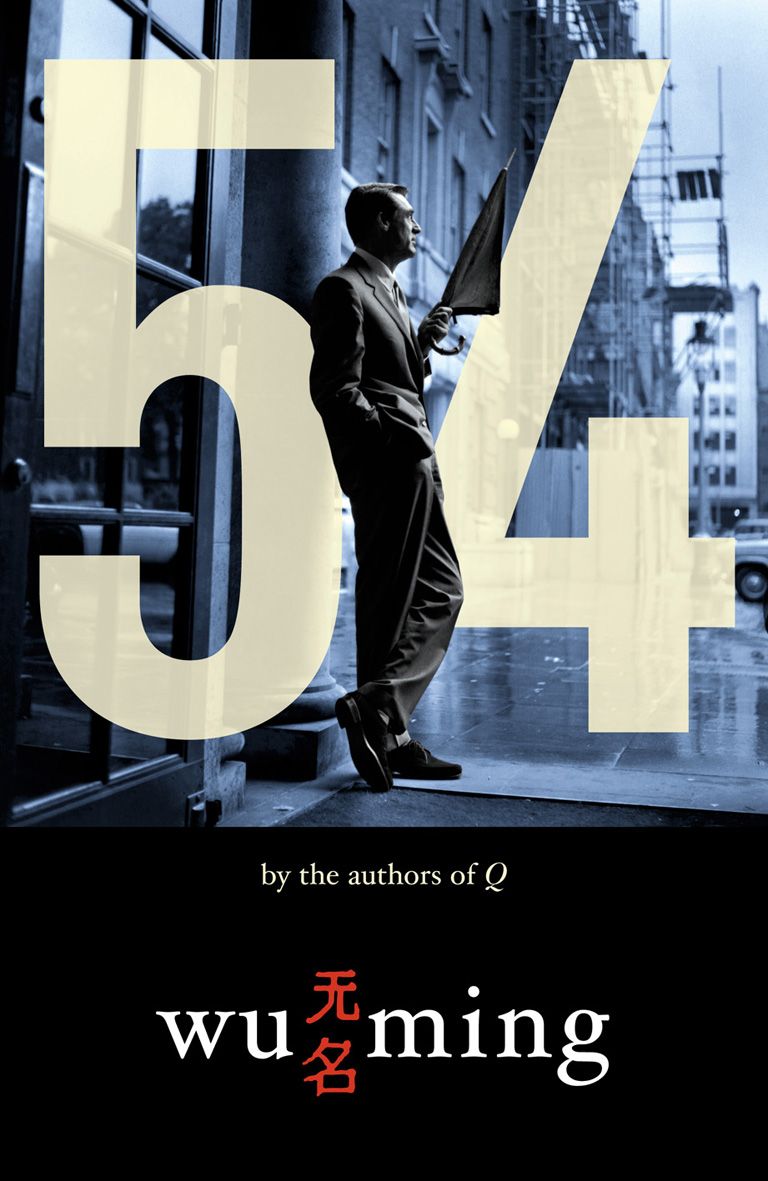

Book cover courtesy of Einaudi.

No matter whether they are authored by the individual or collective, all the stories are attributed to the “Wu Ming” pseudonym. Forwarding their work as a collective counters the climate of individualism and intense fixation on accreditation particularly prevalent in the creative industry, and one of their most enduring political protests.

Each of Wu Ming’s novels propose revisions of real-life events that were “previously unpublished.” Memory is a malleable construct, and Wu Ming wields such a tool with pleasure. Stories are at once serious and satirical, reading like both a political manifesto and thrilling tale of espionage. Their latest novel, UFO 78, investigates 70s counterculture and the extraterrestrial sightings in Italy against the backdrop of president Aldo Moro’s murder. Like their previous novels, the past is continuously subjected to the cultural, social, political, religious, and social urgencies of the present. The questions surrounding the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro also mirror the conspiracies that surround Wu Ming, whose sprawling epics have been questioned as the work of conspiracy theorists—whether that be addressing or even beginning such theories.

For a rare interview, ahead of their appearance at the Berlin International Literature Festival, Agnes Maggie Shu met two of the faces behind the writers’ collective: Wu Ming 2 and 4.

Courtesy of Wu Ming.

AGNES MAGGIE SHU: You are an Italian writer’s collective, and operating under a Chinese name—

WU MING 4: It’s a mess! [Laughs]

AMS: [Laughs] Well, why would you look to China?

WM4: We are a bit iconoclastic. Every band needs a name, and we are a band of writers. We have no interest in being photographed. We prefer to speak about our works, our books, and not so much about us. So, the message is that writing is more important than the author. It’s a joke. Wu Ming means “no name”—“anonymous”. We knew when we started our activity as Wu Ming in 2000 that if you read the name “Wu Ming,” it could also mean five names. So, there is a funny and philosophical reason, if you prefer.

Back then, we thought that China was one of the most important countries for the future of the world—and we still think that. It’s not strange to look to China, even if we don't speak Chinese.

AMS: Even when you write works individually, you remain a collective and publish under Wu Ming 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5. Why?

WU MING 2: When we write books, it's still part of the collective project. It’s not an individual project. It’s also interesting to blur this difference between us as individuals. Writing and telling stories is a collective work. It feels comfortable for me to use the name of the collective.

AMS: Why “comfortable”?

WM2: The comfort that you are not alone. I have no fear. Of course, as an individual, I can stand alone, resolve problems, answers questions to critics. But we are stronger as a collective.

WM4: The collective mind works better than a single mind.

Courtesy of Wu Ming.

AMS: Luther Blissett was a “trojan horse to infiltrate mainstream culture.” How has your agenda evolved since instituting the name Wu Ming?

WM4: Luther Blissett was a project, a name, a global assault on culture—not only in Italy. You could become Luther Blissett simply by using the name. There was no central company who decided who could it. We tried to demonstrate that you could build a counterattack on media, the information system—spreading a metropolitan legend through hoax and pranks. Luther Blissett was like therapy for us.

Wu Ming is a much simpler project. In the beginning, we were five, then four, then five again, and now we are three—Federico, Giovanni, Roberto. It’s not a secret. We use nicknames, but we are not really anonymous. There is a Wikipedia page where you can find our names and surnames. We are a project focused on one branch of culture, namely literature.

WM2: We’ve taken many ideas from the Luther Blissett project. The idea of a struggle within the realm of culture. The idea that you can become famous anonymously. You can write books that many people read but no one knows your name. No one knows your face or biography. We refuse pictures or videos; we don’t appear on TV.

When you write a story, you cannot put a complete copyright it. Luther Blissett’s work and Wu Ming’s books share this dedication to Creative Commons. You can share our works. You can copy it. You can download PDFs of our books online, it’s completely free. The only thing you can't do is to make money using our work. You can't shoot a film using our books without consent.

WM4: You can even put your copyright on our work!

AMS: This is a very different mentality to how most artists view their work.

WM2: When we started, the Creative Commons license didn’t exist. So, we actually put something in the colophon of our books in order to give a chance to the reader—something like a copyleft claim [the opposite of copyright], if you will—so that people can copy it.

AMS: You want people to copy your work?

WM2: We want to spread culture. The stories are made to be spread. We don’t like barriers. Our stories are free for everyone. If someone wants to buy the book, they have to buy it—yes, it’s an object. If you want an object, the object has a price. But if you want a story, the story is not mine.

AMS: In what ways does fiction progress your agenda that nonfiction cannot?

WM4: Stories work. It’s a way to describe the reality, to speak to the world. Often, it’s more fascinating than an essay. An essay has a smaller audience, much smaller than novel. A novel is one of the most popular forms of narrative, ever since the Iliad and Odyssey. They were poems, but the basis of it was an adventure novel. Popular literature is a more effective way to share stories that are different from the mainstream, away from the dominant point of view.

WM2: The very power of telling stories means that we have to learn to use this tool to counter this power. If you want to change the world,you have to be ready to imagine a different one. The difference between fiction and nonfiction begins with a commodification of stories. When you want to sell something, you have to put it in a category. You have to say whether it’s fiction or nonfiction. You don’t think about this commodification when you write.

Book covers courtesy of Wu Ming.

AMS: Thinking about today’s image culture, images have become a prerequisite to any text, especially given social media. It makes me curious about your decision to not be associated with any visuals—even your other projects delve into other mediums, but always veer away from the visual.

WM4: Social media is a continuous auto-fiction.

WM2: We are old school and I don’t know if this is a good strategy. But it’s a way to save our lives. We want this struggle. We risk losing our imagination with visual culture, because we don’t need to imagine anymore. This auto-fiction visual culture is something that destroys your life.

AMS: Why?

WM2: All the attention is about who you are. You spend a lot of time building an avatar and moving within the scene. It’s very stressful. You’re continuously looking at yourself.

WM4: What are you doing? What are you eating? What are you drinking?

WM2: It’s a very narrow-minded view. I like to listen, maybe when I’m on a train, to someone speaking about my book who doesn’t recognize me. It’s like they’re talking about someone else. It’s not me. When someone says that my book is terrible, it’s not about me either. It’s about another bad guy, a bad writer.

AMS: Many say your work addresses conspiracy theories, others say you have even started them. How do you see conspiracy in relation to the truth? And how would you respond to people viewing your work as conspiracy?

WM4: Conspiracy is a social narrative. In many cases, it becomes a weapon of mass destruction. Some conspiracy theories over the course of history have pushed people to change their lives—it happened during the French Revolution, for example. Conspiracy theories can indicate a false objective, a false target. They can provoke the wrong sense of guilt.

Debunking is not enough. You need something else. Not just a rationalist approach, but a narrative approach—to counterattack with another theory, with another narrative, that is more effective, stronger, based on facts and even imagination. Not imagination in the sense of fantasy, but as capacity to imagine something else to transform the world. It’s a strategy that we get from magicians. Some magicians even explain how the tricks work to the audience.

WM2: The explanation of the trick is another show. It’s something added to the trick. It’s another trick in of itself. It’s full of wonder.

A conspiracy theory will always have kernels of truth at its core. The narrative that they construct is not based on facts, but the problem is real. So, you have to answer to these people.

WM4: Not to demonstrate that they are idiots, but that they are taking the wrong direction. The problem is real, but not their answer.

AMS: Does it matter whether something actually happened? Or is the narrative that follows more important?

WM2: Both are important. It’s not difficult to find facts, but difficult to find an effective narrative that respects the readers and the facts. Facts don't exist if you don’t find a narrative that explains them.

Facts depend on your point of view. It’s ideological, like any other faith. What’s more important is to choose a point of view—this is the job of the storyteller. The story I tell contains my point of view and declares it. When you tell a story and write literature, you have to choose a point of view. When you choose a point of view, it becomes political. This is the relationship between politics and literature.

WM4: You have to put the facts into a narrative frame. You cannot assume a false neutrality.

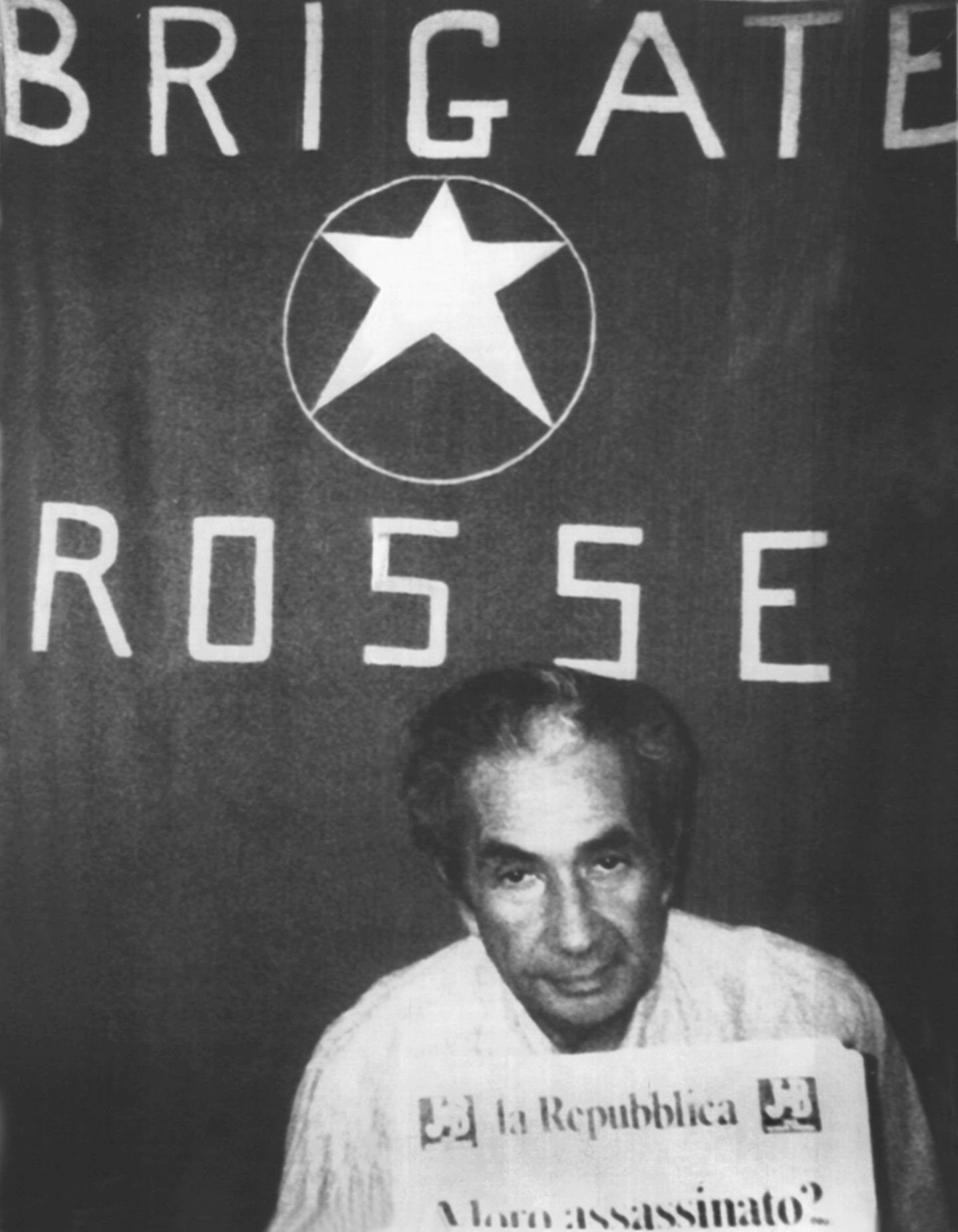

Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro captured by the Red Brigades in 1978.

AMS: The nucleus of UFO 78 first formed in 2006. But it was published sixteen years later. Why was it important to publish the events of 70s counterculture in the context of 2022?

WM4: The 70s were important for Italy, because the situation [surrounding the real-life kidnapping and assassination of Aldo Moro] posed a political turning point. The state decided not to sacrifice its morals to save Aldo Moro's life. It refused to free the political prisoners of the Red Brigades and sacrificed Aldo Moro's life in the name of reason of state. It’s a choice we can also recognize in Margaret Thatcher refusal to free IRA prisoners on hunger strike and let them starve to death in the 80’s. It was a step towards another model, another government, a mass media system where you could not adopt a third position. Aut, aut. “Either or” in Latin.

We were living in a similar situation during the pandemic—again, in this form of embedded mass media, where you had to choose. Are you with public health, with the state, with the pandemic policies? Or were you a conspirator? There was no third position. We were writing this novel during the pandemic about the 70s and realized that we were in a similar turning point in real life. It was the same mental scheme. Aut, aut. Black or white. Either with them or against them.

AMS: So, the UFOs are a metaphor for the COVID-19 crisis.

WM2: It’s not exactly a metaphor, because we don’t use direct metaphors. We write with something in mind, but without direct correspondence to it. We use allegories. Open allegory. The aim is not to create allegories. The aim is to create something that can talk about something else, but that something else can change, too. That is inevitable. When we write, we bear this surveillance power and its control over your life in mind.

There is always an order. You have to be identified. Who you are, why you are outside, whether you are vaccinated, where are your documents. Even in the UFOlogy scene, there were people who wanted to know whether the UFOs are real or not. They wanted to classify the unidentified. We wanted to speak about the right of people to be unidentified, to simply exist in the grey, in the in-between.

AMS: Do you believe in UFOs?

WM2: I believe in other lives in the universe.

WM4: I don't believe it. It is good fiction, but still fiction.

AMS: Do you believe in the death of a novel?

WM4: No. It’s the third, fourth, time that the novel has been declared dead.

WM2: In the domain of culture, nothing can be really dead. Novels have to change, there is always something that changes. But I fear the death of the reader, not the death of the novel. Many young people don’t read books. It’s an anthropological change. They don’t know what it means to read a book, the different kind of thoughts that you can have when you are deep inside a book. This is an experience that you can't have with cinema or video games.

WM4: We are too distracted—destructed, even—by these interruptions.

AMS: Regarding the death of the reader, the current trend has to do with the death of the image—there is such an over-saturation of images that people cannot even process it. Now, text is more effective than an image.

WM2: You’re right, and I made a mistake talking about the death of a reader. Everyone reads, though perhaps they used to read more, once upon a time. It’s the death of the reader of literature.

AMS: Would you consider another seppuku, this time of Wu Ming, and reviving in the form of a new strategy?

WM4: They would have to kill us. With their bare hands. But we are tough guys.

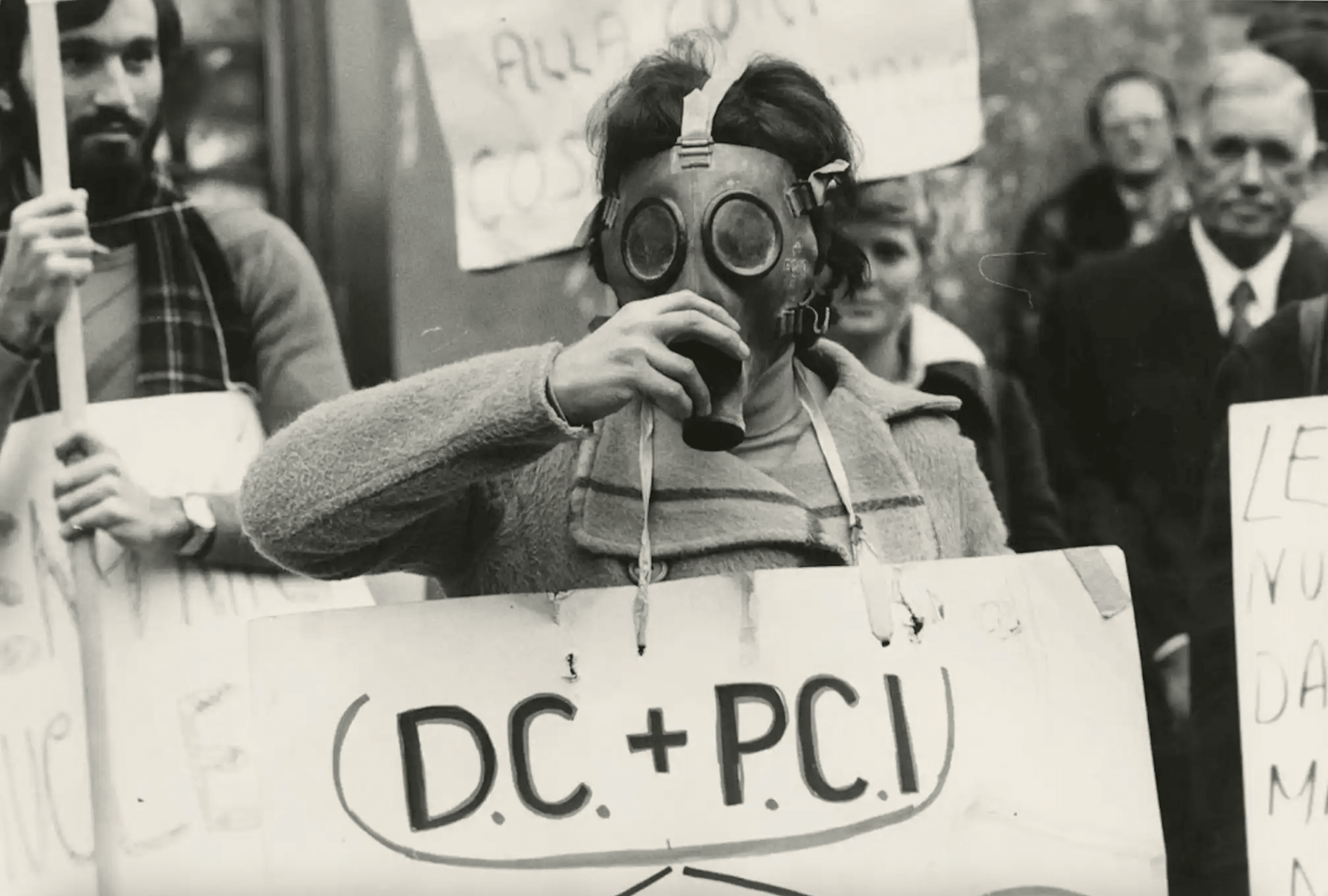

Political Riots in 1978 Italy, photo courtesy The Archive of Modern Conflict.

Credits

- Text: AGNES MAGGIE SHU

Related Content

Death in Sicily: Adriano Sack

Nothing is Linear: Guy Trebay

Writers Who Don’t Understand Their Writing: Travis Jeppesen on Estelle Hoy

GREGORY HALPERN Channels the Manifest Destiny Mysticism of Los Angeles

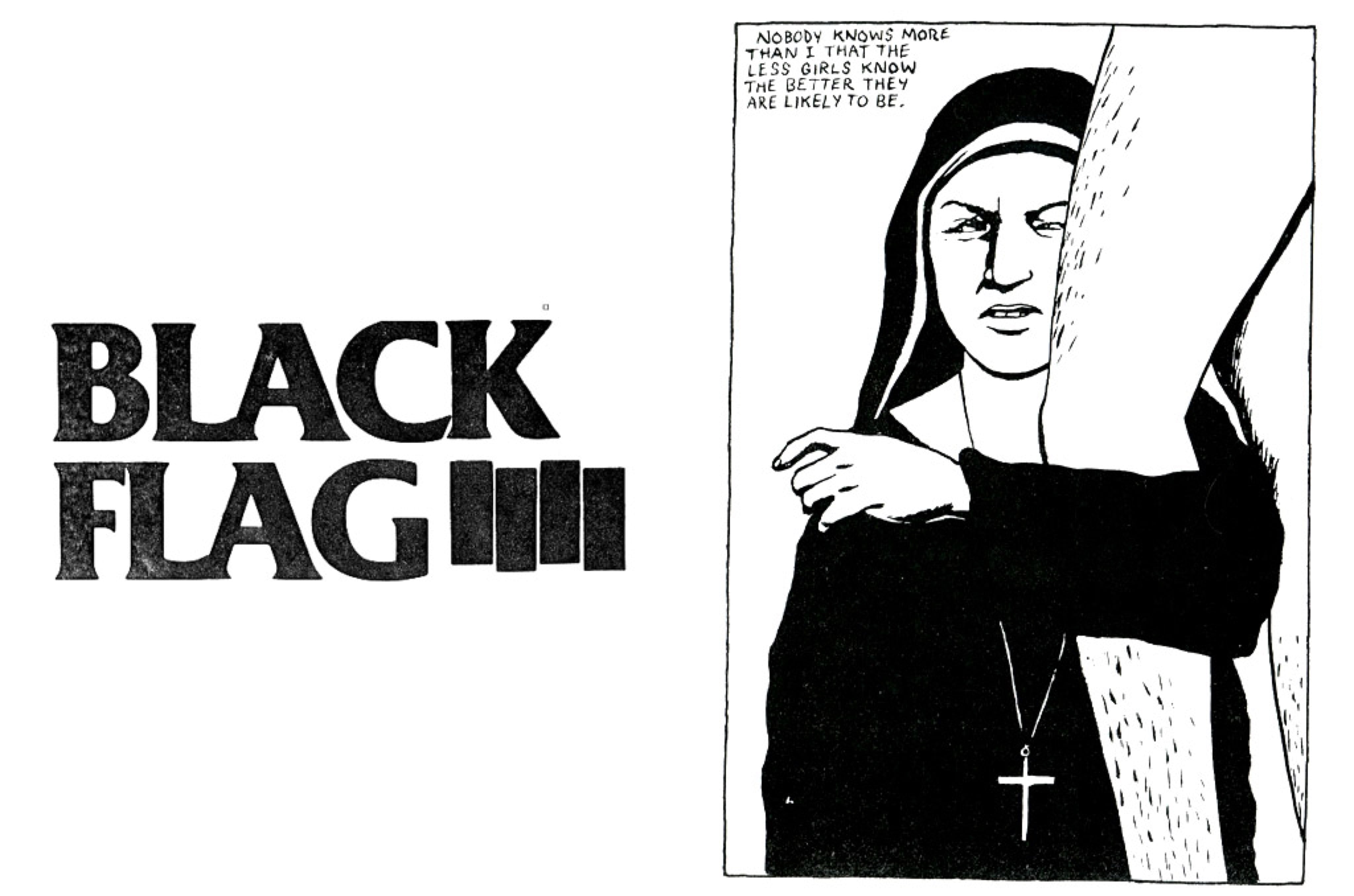

From NOAM CHOMSKY to ICE-T: GLEN E. FRIEDMAN’s Book “My Rules” is a Survey in Being Hardcore

Surprisingly slick art direction from the chaotic world of hardcore punk

Modernism is Still Here (it’s Just Vacationing in the Italian Alps)

Meme, Myself and I

Do We Need to Stop Thinking?

The Ethical Scammer

“A science of misunderstanding”: WOLFGANGER MÜLLER on DIE TÖDLICHE DORRIS

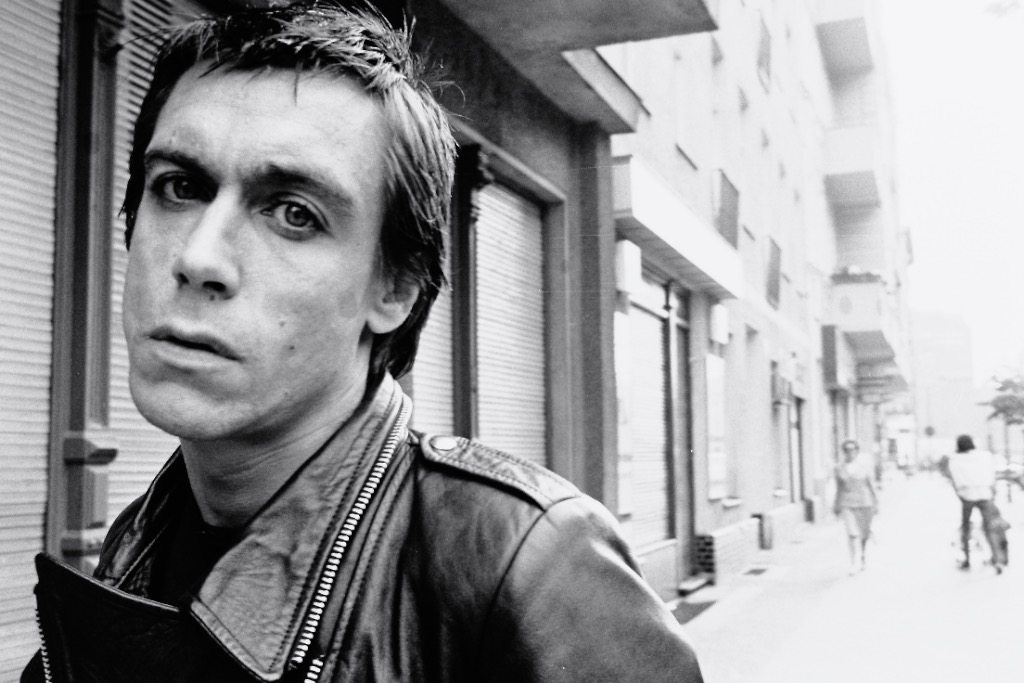

In Love with The Idiot: ESTHER FRIEDMAN Captures IGGY POP in 1970s West Berlin