Do We Need to Stop Thinking?

It is not often that you read a negative exhibition review in an art magazine. Some might notice that the voice of the art critic has diminished to an unintelligible whisper. MITCH SPEED proposes that we need to simply be more playful to become good writers again.

Browsing through one of the more “traditional” art magazines today, those who avidly publish reviews as what feels like the main section of the magazine, means that you first have to fight through a stream of ads by galleries, institutions, fairs, and books. The page after one of these infamous reviews is an ad by the same gallery whose show was just “critiqued” in what might also be described as a rearranged press release. How free can art criticism be in an increasingly — and inevitably — commercialized art world and gig economy, where precariously living writers use reviews as a springboard for their next gallery commission? The focus has shifted from critical analysis to celebratory, promotional writing, and from art criticism to art writing, seen in the rise of corporate partner- and sponsorships, converting the funding and editorial models of art publications. It reflects a changing cultural landscape, where the role of the art critic has been transformed by market forces.

Mitch Speed, a Berlin-based Canadian writer, has long been dwelling on the disconnection between art and its criticism. Speed’s forthcoming collection of essays, published this year by Brick Press, grapples with this subject. Part of the book is “Playing Outside,” a speculative piece concerning the necessity of leaving art in order to become passionate about it again. The essay’s style is loose, as if one is indeed playing outside, comparable to a stream of consciousness. It revolves around the idea that in art and art writing, you need to be in a sub-conscious mode while creating, which can be alternatively translated into a form of play. To create the link between art and the corresponding discourse (anew), one perhaps needs to enter an experimental sphere where labor and recreation are interlaced.

LUCY BROOME: One of the key themes that stood out to me when reading the essays is the playfulness of the production of art, and how that's neglected in art criticism. In reference to the title of the last essay in your collection, “Playing Outside,” how much of art is play?

MITCH SPEED: I started writing “Playing Outside” about ten years ago. My intention was to work through various things that were making me want to leave art altogether. There there was an investment-driven housing crisis in Vancouver, where I was living at the time, and it was crushing the possibility to engage in art in a playful way. There was a literal squeezing out of the capacity for play in artwork and in writing. Play is indistinguishable from the economic concerns of the structure an artist or writer is embedded in because play can really only unfold within free time. When you are working full time and trying to maintain an artistic practice or become a critic there is pressure to get something done in a certain amount of time. That’s something I'm very interested in as a writer. How do you maintain these possibilities for art and writing that are alive and playful, having the capacity to produce magic, whilst simultaneously keeping your eye on the conditions in society that make that possible? This has a lot to do with class, neoliberal ideology, and all that dry stuff.

LB: How much of that involves the need to stop thinking? Do you think there's a tendency to overanalyze in art criticism? A major discussion is if things need to be investigated and analyzed this way at all.

MS: I know what you're making reference to. In one of the essays, I state that writing was a way for me to stop thinking, which sounds counterintuitive because a lot of people would think of writing as a practice that encourages thought. Writing can be an analytical practice, but it's also a way of holding your attention on something, which for me is distinct from analytical thinking. In a fundamental and structural way, good art criticism is essentially the ability to achieve an incredible balance, or dance, between a state of “presentness” and pulling backwards in order to analyze the experience in context. I don't mean that in a new age sense. I mean it in a way of being able to spend time with what's in front of you. Then the viewer isn't always watching you clumsily shift between these two different ways.

LB: It’s interesting how you're alluding to physicality. There is even a more direct reference in the title of another essay, “When the Shape Changes.” Do you view art critics as mediators, and do you think it’s an essential discipline, or is it sometimes better that the viewer perceives the art without that element? What does art criticism really bring?

MS: I think you need both to create an interesting or meaningful relationship to art – not just between the individual and the art but also in the relationship society has to art. It’s an ecosystem or a structure. In my opinion, you need critics. Hopefully, critics bring a lot of experience, particularly experience with the trajectory of contemporary art as it’s developed. This way they can place artworks in context, and you don’t end up with a situation where art is dislocated from history. Based on that, as well as their experience with a lot of artworks, critics can provide a rigor in terms of understanding if an artwork is worth spending time with, or if it’s just leaning on tropes that have been recycled over and over again. Or if it’s just cynical and uninteresting.

LB: You also raise the issue of authorship. Does there need to be a death of the author in art criticism, as Roland Barthes postulated happened in literature? Does there need to be a removal of the critic’s voice, or is the voice part of this ecosystem?

MS: I’m very pro critic’s voice. It’s that voice and the implied presence of an informed and implicated person behind it that gives the discourse life and the public something real to push against. Were criticism to be produced by algorithm-driven AIs, or simply crowdsourced, the conversation would be depleted of dimension, contrast, and energy. That would be hellish. At the same time, Roland Barthes would say that our voices are not nearly as bound to our identities and our individualities as we’d like to believe. The voice is already inherently plural and always fed by a multiplicity of voices which we've ingested throughout life. The best writers know this, wrestle with it, and have fun with it. It’s at this point that criticism becomes art.

LB: The wider topic of this conversation is the disconnect between art and its criticism. What are the reasons for the disconnect?

MS: For as long as I’ve been around, art criticism has been largely defined by a crisis of faith, with respect to the reader’s ability to believe that critics mean what they say. To read contemporary art criticism is to notice that the majority of writers skip over the uncomfortable business of asking whether or not an artwork aroused feelings or responses in them and go straight into interpretation. This is a much safer course of action, because nothing is at stake except for the writer’s ability to display a certain acuity and rhetorical skill. If you stay in the realm of interpretation, you can be sure that no one’s feelings are going to get hurt, and also that you’re not going to spill your embarrassing guts.

“Were criticism to be produced by algorithm-driven AIs, or simply crowdsourced, the conversation would be depleted of dimension, contrast, and energy. That would be hellish.”

To close this disconnect, we’d need critical voices defined by both feeling and thinking, both raw experience and analytical reflection. At present, the conditions that would support these types of voices don’t exist. These conditions are time and a reasonable expectation of job security. Time because writing this kind of honesty and nuance is incredibly labor intensive, and job security because the art writing industry, as it currently exists, makes positivity compulsory and punishes critical honesty. We’d also need long-term, trusting relationships between editors and writers, which is something that the gig economy has decimated. Quality criticism requires intimacy, both between the critic and their subject, and between the critic and their editor.

LB: I suppose the elephant in the room is hierarchy. Perhaps there is a disconnect because the viewer interprets art in one way, whilst the critic’s interpretation deviates from that. It is based on an institutionalized way of analyzing and interpreting art, which the viewer is not always familiar with. A lot of critics have a tone that seems to look down on the viewer and reader, which can be seen as creating another barrier between the individual and their access to art.

MS: To a certain extent, the stress test of art is how people who aren’t specialists react to it. A person should not require an art history or critical theory PhD to engage with art. Critics bring something very important and particular to the table, but I hold that importance and particularly as being distinct from the idea that a trained critic’s viewpoint should enjoy the final word. We need both the popular vocal chorus and the specialist position. We get in trouble when we try to decide that there should be one or another. That’s how we deliver ourselves into a stalemate between populism and elitism, which is as bad for art as it is for society.

LB: Returning to your text, what was the inspiration for the book’s working title “When the Shape Changes?” You alluded to physicality earlier, and the title seems to be a direct reference to that.

MS: The title captures the kernel of what good art does when it works. I'm talking about the moment when materials or forms that seem very ordinary when encountered in a raw state are somehow suddenly separated from themselves — when they transform in the moment of encounter. The best art knocks us out of deeply habituated responses to mechanisms and impresses upon us the singularity and weirdness of otherwise expected things: material, shape, color, or the events of a person’s life or politics. This is an old idea. It echoes Bertolt Brecht’s “estrangement effect.” I’m interested in a type of psychedelia that occurs when ephemera escape the category of things and experiences that we already know and that we’re numbed to. It’s the feeling of the expected appearance of reality cracking for a moment — something else shining through.

LB: I noticed you included the Walter Benjamin quote, “For someone who is past experiencing, there is no consolation.” Did his writings on art influence yours, or did that quote just resonate with you?

MS: My relationship with Walter Benjamin, like a lot of peoples' relationships to Walter Benjamin, is simultaneously very serious and a bit cringe. It’s in this spirit that I quoted him. When I was in art school, he was going through a major wave of popularity. It became a cliché to quote him. I associate his work with the experiential potential of criticism itself. A person could say the same about a lot of great critics, of course. That quotation comes from a very dense passage on Baudelaire. It’s very hard to distil a single meaning from the passage. He is circling around important ideas, showing them to you, but also refusing to let those ideas calcify or settle. That to me is the essence of transmitting experience through words. There’s an intense laboriousness to it, but also beauty in the extreme. But yes, the quote resonated with me. I agree with the weight it lays on real, complex experience, and I have a taste for its melodrama, its tragedy.

LS: How does this link back to your practice? Do you feel a contradiction being an artist and a critic? Do you think too much when you're trying to create?

MS: At this point the contradiction has pretty much dissolved. Hopefully, my ego occupies less space in the room these days. I actively worked through this in one of the essays in the book, which is about artists who write. I started writing that essay to figure out what exactly that type of writing can do for our relationship with art.

There are certainly artists who intensely schematize their work before they start making anything. But for me that just results in a system meltdown. When I make art, it comes through a very simple process of doing one thing, reacting to that thing, and doing another thing. I need to be in the work, and then one move follows another. Otherwise, I get all dizzy and lost. I prefer to have my nose a little deeper in the mess. This kind of intentional short-sightedness produces effects that can't be strategized.

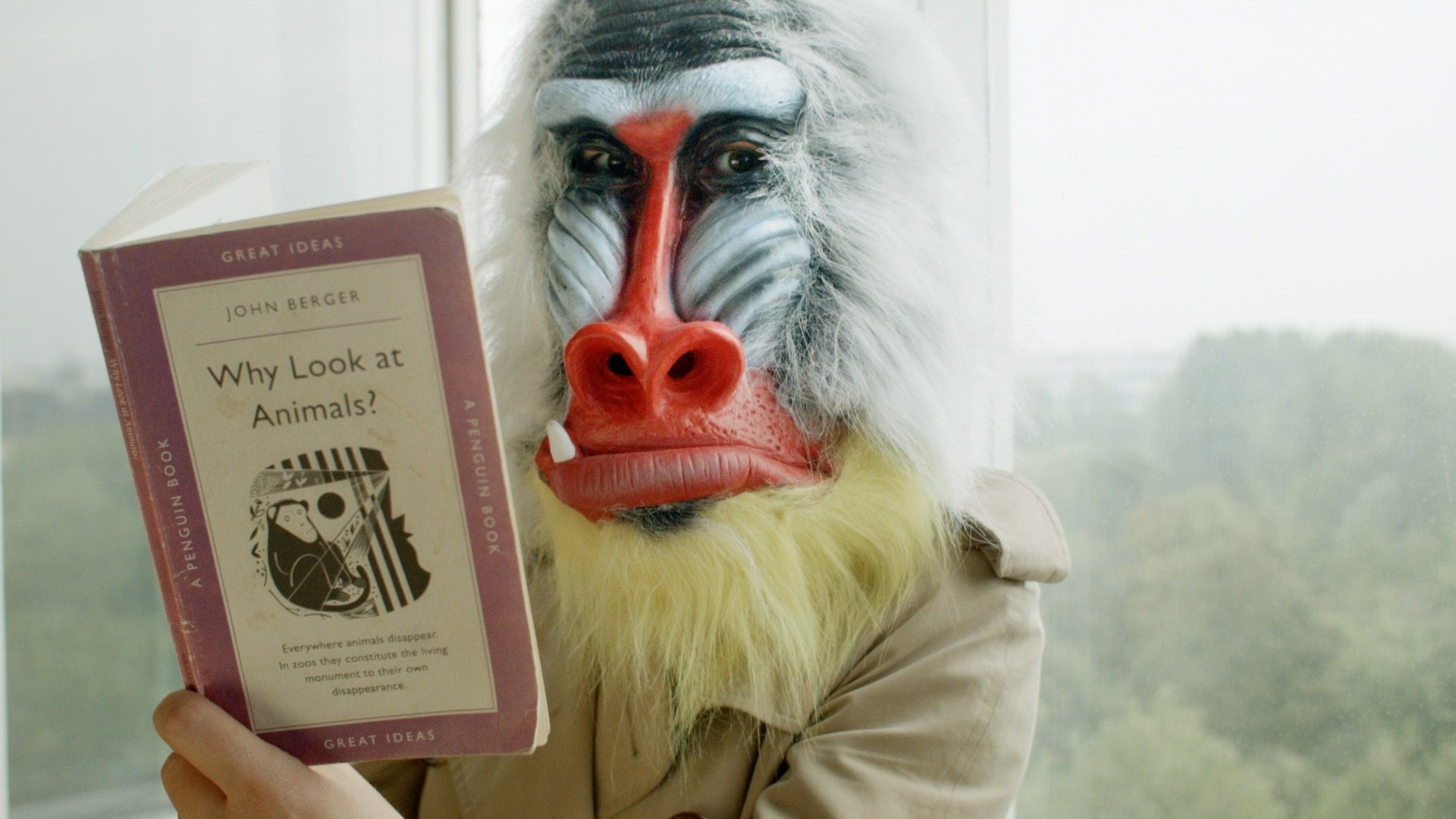

LB: Walter Benjamin has an interesting stance in his seminal work The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, which we were referencing before. He observes the effects of photography and film’s introduction in the reproduction of art, and as art mediums themselves, asserting that film has no “aura,” deviating from the almost religious fascination with art and advocating for the viewer’s involvement. My initial contact with your work was through the book that you wrote on Mark Leckey’s video “Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore” (1999). Do you think works such as this video serve to reduce the hierarchy between art and viewer?

MS: That is probably true. One of the things that I love about Leckey’s video is his position on how it exists in the world. “Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore” is the same artwork whether you see it in a gallery or on his own YouTube channel. I once asked him if I could show it at the launch of the book, and he seemed almost annoyed at the question. The answer is, you can show it anytime you want to. Video has the potential to break these rules of access that say that you have to encounter something at a museum or a gallery for it to be legitimate. What in large part makes “Fiorucci” such an incomparable artwork is the sense of engagement and resonance that it achieves simultaneously inside and outside of the so-called art world. It’s a part of the official canon now. There is no doubt about that. But it is also profoundly accessible. That's why it sets such a high bar for what art can do, and who it can reach.

Credits

- Text and Photography: LUCY BROOME

Related Content

Viscose: The World’s First Bagazine of Fashion Criticism

A Martine Rose Slip: JORDAN/MARTIN HELL

BLAU JOB

Open House: A Look Into STUDIO OLAFUR ELIASSON

032c x WHITE MILAN: The “Passages” Exhibition Guide

Art Critic JERRY SALTZ and 12 Supermodels Discuss the Selfie

JOHN BERGER, The Happy Centaur: Visiting a Rural Futurist

BRAND LOYALTY: DIS Magazine for 032c