Meme, Myself and I

|Cassidy George

In today's media landscape, a book review is often a slap on the back. A handshake among colleagues that says, “well done.” But we have never been afraid to offer critique when critique is due. In our print section Berlin Reviews, we've always tried to take the propositions of a book seriously and push them to their extremes.

Archive Berlin Review from our issue #40

In the 1939 fIlm The Wizard of Oz, Toto peels back a curtain to reveal the real wizard, who is not the mystical apparition he projects above the throne but a self-professed “humbug” from Omaha. Revisiting this scene on YouTube after scrolling through a face tuned Instagram feed, I found the dissonance between the squat man with the microphone and the powerful image he presents no longer felt particularly dramatic or deceitful. Anyone on social media, which mandates the creation of an often enhanced or distorted virtual “self,” engages in a similar process in their daily life.

The Extreme Self: Age of You plays the role of Toto in print. Over the course of 250 pages, authors Shumon Basar, Douglas Coupland, and Hans Ulrich Obrist reveal to readers, hidden behind screen curtains, their own wizards. The “extreme self” refers to the engineered avatar each of us inhabits in any online life.

By harnessing the mass-communicative power of memes, the book updates the concept of the graphic novel. Punchy text is matched with a curated selection of images supplied by an impressive list of contributors, which includes Berlin-based artists Anna Uddenberg, Asad Raza, and Pan Daijing – alongside buzzy names such as those of designer Craig Green, Korean DJ Yaeji, and filmmaker Miranda July. In the first chapter, a statement is superimposed over a memeifed artwork by Anne Imhof: “We’re not interested in other people so much as we’re obsessed with how they present themselves.

The trio’s first publication, The Age of Earthquakes: A Guide to the Extreme Present (2015), was a rattling refection on the absurdities of life in the digital age. The Extreme Self, however, addresses the impact of these absurdities on its readers themselves – making for a far more personal affair. Your own easily triggered, constantly multiplying, over-empowered, and ultimately dispensable extreme self is the protagonist, antagonist, and central conflict of the story. And our extreme selves are to blame for our extreme world, in which Q Anon forums dictate national politics, Siberian troll syndicates “harvest likes” for money, and the comments section is the new Colosseum.

Despite their apocalyptic tone, the authors’ illustrations of extreme selfidom yield delightful vignettes about such topics as the rate of authorship in the Icelandic populace, selfie-related deaths, and Savanna Tomlinson’s viral high school yearbook quote: “Anything is possible if you sound Caucasian on the phone.”

Although The Extreme Self does troll the trolls, it is ultimately a rehabilitation program for psyches that have become increasingly pixelated by the digital age. And, like any good therapist, the book asks leading questions (“Could the battle ground of the 21st century be decreasingly geopolitical and increasingly about geoselves?”), makes memorable declarations (“Feelings now legitimize lies”), and offers sound advice (“There’s no point in being horrified that the on-line world has replaced the real world–it’s just a fact of life”). The authors aptly critique right-wing conspiracy culture, but the haunting realizations born of its prompts – think, “What if [the extreme self] is the only version of you that matters any more?” – are their own kind of red pill. Readers beware: once Toto draws back the curtain, it shatters not only the image of the wizard but the entirety of Oz.

The Extreme Self: Age of You is published by Walther König

Credits

- Text: Cassidy George

Related Content

An Internet the Size of a Room: Berlin Review

In Outer Space with WILL ALEXANDER

Half a Century of Civilian Sketches from the UK’s UFO Desk

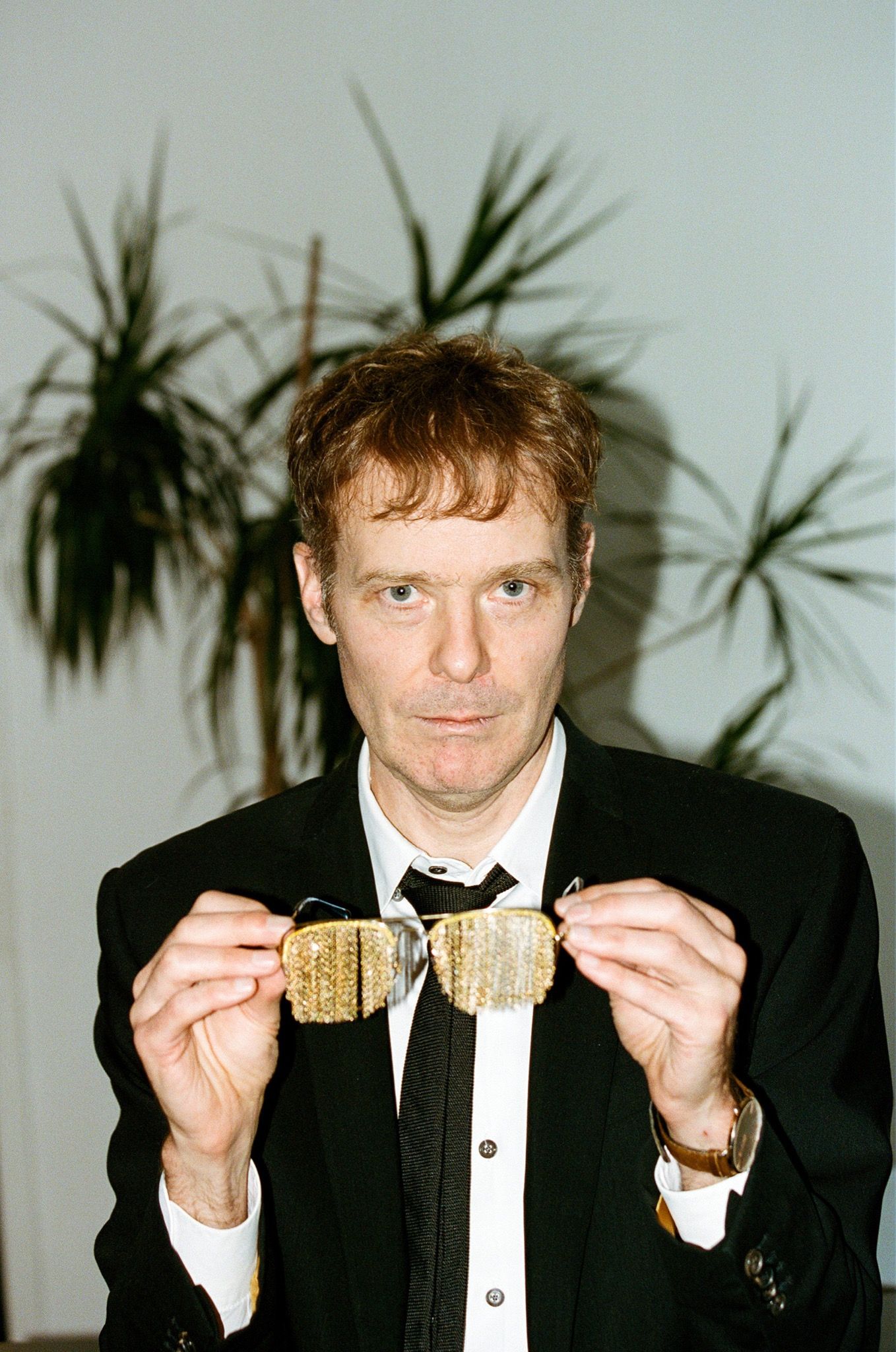

TOM McCARTHY Incarnate

Love in the Time of Prompting: SHUMON BASAR and Y7’s CORE+LORE

Weaponized Irony: A Roundtable on Trolling and Politics

ARCHITECTURE POST INTERNET: ANDREAS ANGELIDAKIS in Conversation with Carson Chan

YEAR OF THE PIG: JON RAFMAN and the World’s Hungriest Fetish