Modernism is Still Here (it’s Just Vacationing in the Italian Alps)

If architects follow technical codes in the studio, do they get to break aesthetic codes on vacation?

Architects have long used travel as a muse, since the times of the Grand Tour, a Rumspringa of bourgeois nostalgia. A drawing by Henry Parke in London’s Soane Museum shows a young British architect on a deranged journey up a ladder towards the top of a ruined temple—wearing a top hat and holding a yardstick —with a vertigo-inducing view of Rome whirling behind him. Such is the danger-desire of a true holiday. The pleasure of curiosity comes with the promise that you may never return home.

In their follow-up to their critically insightful Italomodern, architect brothers Martin and Werner Feiersinger sojourn across North Italy once again to present us rare strains of modernism left looming in the alps. Italomodern 2, is another romp through the rationalist, organic, and brutalist buildings of the region, organizing 132 specimens chronologically from 1946 to 1976.

The book’s purple-velvet cover seduces a viewer into a stash of architecturally sensitive images. Breaking the careful symmetries of the classical architecture book, the photography is snapshot-like, with parked red Fiats littering the frames. The approach imbues the volume with a wanderlust that is both whimsical and dark, one that reminds the viewer that 120 Days of Sodom was set just a stone’s throw away across the Swiss border. In certain flashes, the pictures take on the bureaucratic amateurism of crime scene photographs, such as Mario Cavalle’s Case Zucca, which looks as if the roof of a Tuscan turret had been decapitated and turned into a summer cottage.

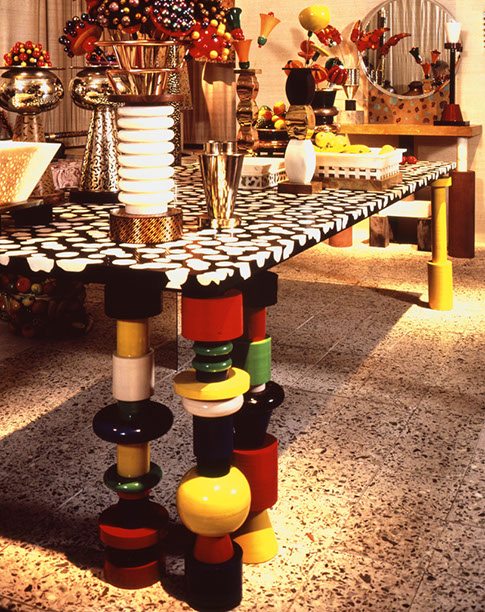

Elsewhere, yet more sinister approaches to the holiday jaunt are directly breached. Tucked in the Alpine village of Corte Di Cadore, Eduoardo Gellner’s Il Campeggio is a cultural experiment commissioned by energy company ENI in 1958. Executive-level employees could spend time off in one of over 300 villas. The wooden frames of Gellner’s “permanent tents” are sly emulations of their alpine surroundings, incrustations of the modernist project onto the geology of the Dolomite Mountains. The obsessive architect designed everything from light fittings to the furniture that was conceived in collaboration with Friuli manufacturer Fantoni. An über-branded gesamtkunstwerk, the dinnerware, cups, and even bedcovers were embellished with ENI’s ominous mascot, a six-legged dog. Through the sullen, forensic timbre of the Feiersingers’ lens, the colony becomes a Tarkovskian “Zone,” both a strike against “rustic” architecture and a base for corporate mind-control.

In Italomodern 2, leisure becomes a space of pastiche, mutation, and sometimes manipulation. Rules are never broken, but simply left at the office. Here, modernism itself has called in sick and gone on a delirious Italian escapade. Sunblock and Chianti optional.