In The Clouds with Stefan Marx

|MAX ROSSI

One thing you might not know about artist Stefan Marx is that he is a commercial aircraft connoisseur. The Berlin-based drawer and painter, who has worked with Comme des Garçons, Supreme, and IKEA, can delineate the exact tail length and wing curvatures that distinguish an Airbus from a Boeing, along with the intricate and often obscure workings of airline planning operations.

Stefan Marx portrait taken at Lufthansa Lounge at Art Basel Miami Beach. Photography: Lukas Mengeler. Courtesy the artist

This unlikely expertise is not fostered by formal piloting experience or studies but rather by a decade of sketching airplanes. Among other hubs, Frankfurt Airport has often doubled as his studio during long layovers, with fleeting scenes from the tarmac and the air finding their way into his notebook.

Most recently, his plane-spotting fixation culminated in a collaboration with Lufthansa for their private lounge at Art Basel Miami Beach. There, he showcased a mix of his most iconic works alongside new compositions inspired by the experience of flying.

Following this project and on his second day back in Berlin, I sat down with a slightly jetlagged Marx—jetlag being, for him, a deeply inspirational state of consciousness, as evidenced by the title of his Art Basel book First Class Jet Lag Queen—at his apartment in West Berlin. Over tea, we spoke about the power of an artist’s eye, the joy of traveling, and how to find harmony between gallery spaces, fashion runways, and airport lounges.

Installation view of Stefan Marx's booth at the Lufthansa Lounge at Art Basel Miami Beach. Photography: Lukas Mengeler. Courtesy the artist

MAX ROSSI: Your work spans magazines, fashion collaborations, books, album covers, murals––and now, even plane paintings. How did it all start?

STEFAN MARX: Growing up in the German countryside, far away from everything urban and fashionable, I became interested in graphic design and streetwear through skateboarding magazines. Not long after, I started sketching my own designs––which later evolved into the streetwear brand Lousy Livin––because I was bored of spending my little pocket money on American brands that nobody in my rural environment could relate to.

It had a lot to do with the DIY spirit of the late 80s and early 90s. When I came into contact with magazine culture, which was much bigger than it is today, I also began creating my own fanzines, mostly related to skateboarding and drawing. This teenage fanzine obsession led me to artist books, which have been a staple in my artistic practice ever since. My first artist book, I’m A Bad Guitar Player But I Love To Do It. It’s A Good Thing To Do, came out in 2003. Since then, publishing and distributing these books—through publishers, at art book fairs, or even via self-publishing—has remained an integral part of my work.

MR: Is there a difference between the work you can show when you self-publish versus going through a publishing house?

SM: Absolutely. Self-publishing feels much more immediate. I’ll sit down at a coffee shop to draw, run the designs through my own copy machine, and it’s almost like painting––completely raw and spontaneous. I can print a small edition on the spot, usually 20 to 100 copies, and they’re out in the world right away. When you go with a publisher, there’s a whole process of printing files as well as arranging everything from the ISBN number, dates, distributions, etc. It’s slower and more structured but equally rewarding.

Right now, I’m collaborating with Hatje Cantz on a project compiling some of my typography-based works. For this book, we selected three texts, which were then examined by art historians, curators, and editors to frame them within a broader context.

For this project, I worked with Michael Satter, an exceptional book designer who shaped the entire layout. The process was highly collaborative, which I really enjoyed. That said, when I self-publish, I do everything myself––from start to finish. It’s a completely different energy, and I think both approaches have their own unique value.

Drawing artwork taken from Stefan Marx Berlin Drawings 2 (2022), edited by Nieves and supported by Carhartt WIP. Courtesy the artist

MR: For those unfamiliar with your work, could you outline its main visual elements?

SM: My artistic practice revolves around painting and drawing, with drawing being the more spontaneous medium. I always have a sketchpad with me, no matter where I go or the occasion. Most of my drawings are black-and-white, which makes them quick and easy to create without requiring much time or a dedicated studio setup. In contrast, my larger canvas pieces are more complex. They’re colorful and sometimes include oil paint, which can take weeks to complete. I love both approaches and try to merge them whenever I can. Occasionally, I’m commissioned to create large-scale murals. For example, I collaborated with the German curator Britta Peters on Urbane Künste Ruhr in the Ruhr area of Germany. I created three large typography pieces inspired by coal miner shanties from old mining unions. These songs captured both the workers’struggles and their way of life, and I transformed some of the lyrics into visual works.

My interest in typography goes way back to my teenage years. I wanted to surround myself with songs I loved, but not in the usual way of playing the music. Instead, I took lyrics and quotes and visualized them. It’s a bit like reading in silence—it evokes the same feeling for me. Even now, in my home, I have many pieces like this carpet [points at a rose-patterned carpet a few meters away] that says, “Love Letters.” I’m drawn to certain words and enjoy giving them a visual form, whether on canvas, in sketchbooks, or through books.

Stefan Marx, Weak Passwords, 2023, acrylic on canvas (left) and Moonlights, 2016, acrylic on canvas (right). Curtesy Galerie Karin Günther and the artist

MR: You draw your inspiration from everyday moments. How do you find such beauty and humor in the ordinary aspects of life?

SM: For me, drawing is about looking closely—really paying attention to understand things, almost like studying a still life. Sometimes it’s objects; other times, it’s the way people show themselves. Funny hats, strange haircuts, oversized T-shirts with bizarre prints—these details capture my attention and feed directly into my drawings. That’s why airports are some of my favorite drawing spots. There’s this incredible diversity: people from all over the world in a rush, exhausted from long-haul flights, or casually having a beer at 10am. Everyone’s running in different directions, yet they never truly meet. It’s a surreal mood.

I try to catch all of this—not only at airports but also here in Berlin, especially on the U-Bahn. Sometimes, I’ll sit next to someone talking on the phone and overhear an interesting quote, which I promptly write down. As an artist, it can be a very solitary practice, so I enjoy immersing myself in the crowd. I’ve published two books about my Berlin drawings, and they’re one-to-one replicas of my sketchbooks.

MR: How did you develop your observational skills?

SM: It started during my civil service in Germany. Back then, you had two options: join the army or do the service, and I chose the latter. I was stationed in Cologne, but we had these Deutsche Bahn tickets that allowed us to travel for free back home to visit family. I ended up taking a lot of three-hour weekend train rides. This was before the internet, so there was no phone or Instagram to kill time. I’d read or listen to music on my Walkman, but mostly, I spent the time studying my surroundings.

This habit evolved when I moved to Hamburg for university. I’d often find myself wanting to note something down, but without a sketchbook on hand, I started drawing on the backs of flyers or any scrap of paper I could find. That’s when I developed the habit of always carrying a notebook. It’s been with me ever since. I love it.

It’s also practical. I’m often working with very limited time. Sometimes, I only see someone for a second or two, and there’s this one detail that catches my eye, something I want to capture like a photograph. I don’t have the time for a highly detailed representation—it’s all about immediacy.

Drawing artworks taken from Stefan Marx Berlin Drawings 2 (2022), edited by Nieves and supported by Carhartt WIP. Courtesy the artist

MR: Airplanes have been a recurring theme in your work for over a decade. Where does this interest come from, and how has it evolved?

SM: I started traveling by plane quite late in life, as I never really flew with my family. My first trip was at 18, which feels quite late for today’s younger generations. When I discovered flying, I was so fascinated that I immediately adopted it into my practice. I loved the idea that you can visit so many places on your own—all you need is some money. It was like rediscovering the beauty of travel, and I was hooked. On my first trip to Japan, I passed through Vienna Airport and had a long layover on my way back. That’s when I started to notice the planes and sketch them. I was amused by their design and surprised at how comfortable and relaxing the experience of flying was. I began paying attention to the planes’ designs—the logos, the fonts. I realized how many different airlines there were, and I started learning about the processes behind them: domestic flights, long-haul, intercontinental. All of it; big planes, small planes. Then I began studying the planes themselves—learning the difference between Airbus and Boeing, Embraer and Bombardier. Most of this knowledge came from drawing them. Honestly, I’d draw it first, and then understand it. Especially the small details—how tall the tail is, the shape of the wings, the cockpit.

I was living in Hamburg, and the Airbus factory is there, one of only two in the world, the other being in Toulouse. Because of this, many planes fly into the Airbus airport for test flights. Sometimes, you’ll even see American companies flying over Hamburg. Eventually, I understood how the airline hubs work. For example, Lufthansa has hubs in Munich and Frankfurt, flying back and forth between the two, and each airline has its own system. It’s a fascinating global network, and I’ve really enjoyed learning about it.

MR: So, what is your favorite airplane model to draw?

SF: It's the Airbus A350-900.

Airplane drawing of a Lufthansa Airbus A320 at Munich Airport by Stefan Marx, taken from his latest artist book First Class Jetlag Queen (2024), published in collaboration with Lufthansa. Courtesy the artist

MR: In past interviews, you’ve mentioned that you want the people who look at your drawings to feel as triggered as you were when creating them. What are you trying to evoke with your airplane drawings?

SM: I mostly want people to feel the beauty of travel—the beauty of meeting new people, of discovering the personal journeys of others. Of course, sometimes it triggers memories like, “Oh, I flew with this airline and had terrible turbulence,” or “I lost my bag,” or other negative experiences tied to travel. But I try to capture the whole spectrum. It’s been really interesting to get feedback when people look at my books and how it triggers personal memories for them.

Passenger drawing on a Lufthansa sick bag by Stefan Marx, taken from his latest artist book First Class Jetlag Queen (2024), published in collaboration with Lufthansa. Courtesy the artist

MR: This all leads to your collaboration with Lufthansa at Art Basel Miami Beach. What is the idea behind it?

SM: For the past 20 years, I’ve been an avid Lufthansa fan, mostly because I associate many of my fondest travel memories with flying with them. I’ve drawn their planes a lot, not only because they’ve been part of my personal travel experiences but also because I admire their design history and hubs. I love Frankfurt Airport, especially the view from the big windows looking out at the tarmac. For a while, I even considered applying for a job at Lufthansa just to spend more time in that environment. [Laughs]

When giving lectures and talks all over the world, I made my interest in partnering with them quite public, and at the end of this summer, they contacted me to collaborate for their lounge space at Art Basel Miami Beach to show my work there.

We developed various ideas together, and I told them that many of my paintings are influenced by travel experiences—like the moonlight from a window seat, the jet stream tailwind on a flight from North America to Europe, or waking up to a sunrise after a night of flying. I’ve created lots of work around these themes, but for Art Basel, I reworked some pieces and even changed their color palette to fit into a larger composition. We displayed big paintings and created smaller giveaways, like an artist book featuring planes and passengers that I’ve drawn over the past decade, some of which were sketched on sickness bags.

Installation view of Stefan Marx's booth at the Lufthansa Lounge at Art Basel Miami Beach, including his artist book First Class Jetlag Queen (2024). Photography: Lukas Mengeler. Courtesy the artist

MR: You mentioned your first trip to Japan. What travels have influenced your vision the most as an artist?

SM: I think Japan has been by far the most influential. Since my first trip, I’ve returned often to collaborate with local galleries and companies, even participating in art book fairs there. I’ve also had some fascinating trips to the South Pacific, such as to the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. For me, it’s all about the nature and that feeling of remoteness, which I try to reflect in my work.

Stefan Marx walking portrait featuring a First Class Jetlag Queen t-shirt created in collaboration with Lufthansa for Art Basel Miami Beach. Photography: Lukas Mengeler. Courtesy the artist

MR: Your work bridges street culture, galleries, and major brand partnerships. How do you maintain your voice while navigating such diverse environments?

SM: There must be an overlapping interest. If you look at the art, music, and fashion scenes, these connections go way back—it’s not something my generation invented. I first encountered Raymond Pettibon’s artwork on a Sonic Youth cover, not in a gallery or museum, and that was a major touchpoint for me before I even entered the gallery and museum world. I realized there was power in artists doing record covers and creating work that could travel outside the art world. I’ve always tried to do that with my own work whenever the right opportunity presented itself. When I collaborated with Rei Kawakubo for Comme des Garçons SS-18, her assistant asked if they could adapt one of my canvases on a cape for the runway collection. I thought, “Why would I say no to this?”

When I collaborated with IKEA, for example, it was because I’ve always been interested in flower vases and pottery. I’d already made some with KPM here in Berlin, or even on my own with a ceramic maker. But when Sarah Andelman from Colette curated a special line with IKEA featuring five amazing artists, it really struck a chord with me. It made me realize I could also do something with IKEA—especially because I could create something that would bring people joy and be affordable for anyone. With projects like that, there has to be something in it that triggers me, something I can’t do myself. I can’t make a glass vase like I did with IKEA, or a garment. And with Lufthansa, it was a dream come true. I get a lot of requests to simply use my work for this or that without wanting to engage in a dialogue with me, and I often say no to those.

Credits

- Text: MAX ROSSI

Related Content

An Orgy of the Mind With Charlie Fox

Mire Lee’s Fountain of Filth

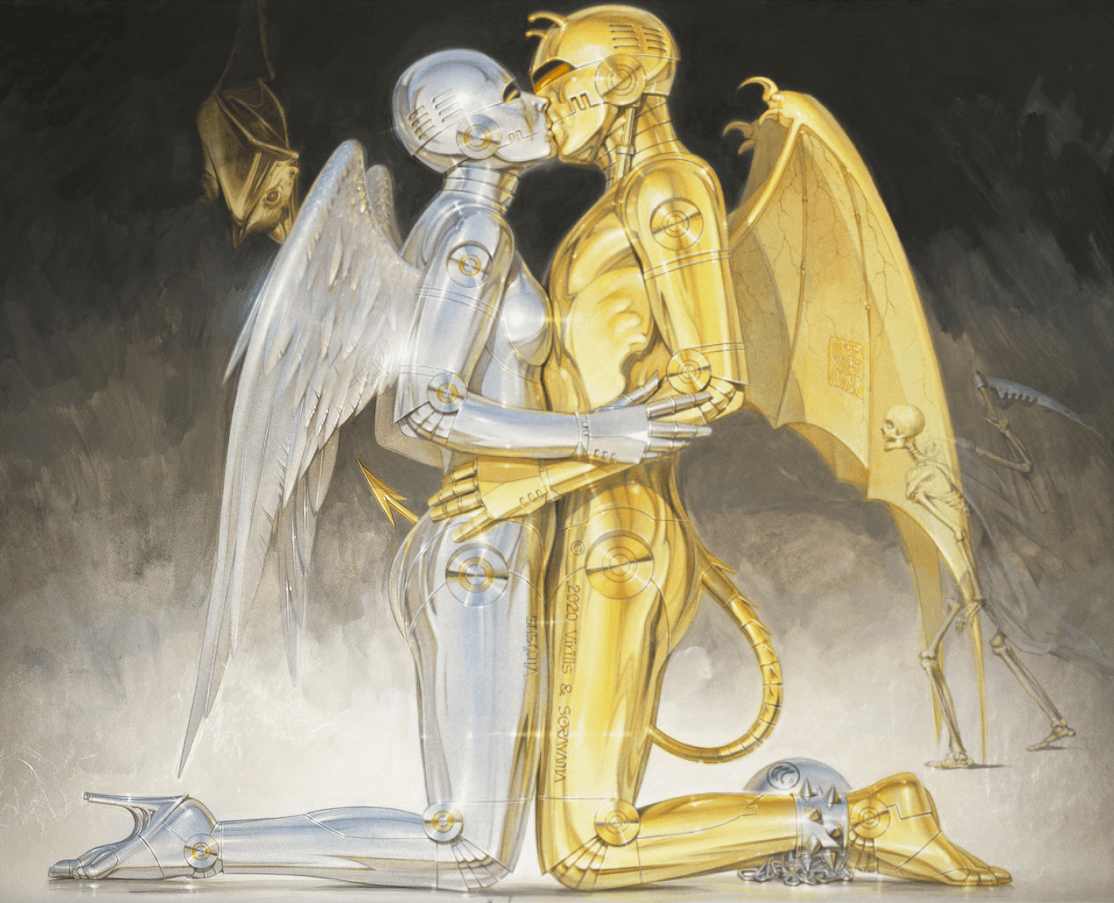

Hajime Sorayama: What I Draw Are Human Beings

Julian Charrière: Ancient Reefs and Active Volcanoes

The Politics of Beauty: Tyler Mitchell

032c Issue #46 “Aphex Twin” Winter 2024/25

The Denatured Machine

Are We Artless? NATASHA STAGG

Welcome To Hell: Ben Ware On Extinction

Nothing is Linear: Guy Trebay

A Gateway to Forbidden Realms: Rob Kulísek

Moncler and Rick Owens Craft Personal Sanctuaries