Moncler and Rick Owens Craft Personal Sanctuaries

|SHELLY REICH

When Joseph Beuys arrived in New York City in 1974, he was met by assistants who wrapped him in a large felt blanket, placed him in an ambulance, and delivered him to the René Block Gallery in SoHo. Beuys’ feet never touched American soil; his only interaction was inside the gallery, where he spent three business days with a live, wild coyote for the performance I Like America and America Likes Me.

Moncler and Rick Owens’ creative work has taken inspiration from this Beuys performance, where the sterile gallery environment became a sanctuary for emotional and spiritual dialogue between man and nature. Owens takes that concept of the gallery as a cocoon of self-construction and applies it to his design of spaces and garments. Whether it’s previous projects with the brand like customizing a tour bus or the insulating protection of a duvet jacket, his work serves as a metaphor for self-preservation and transformation.

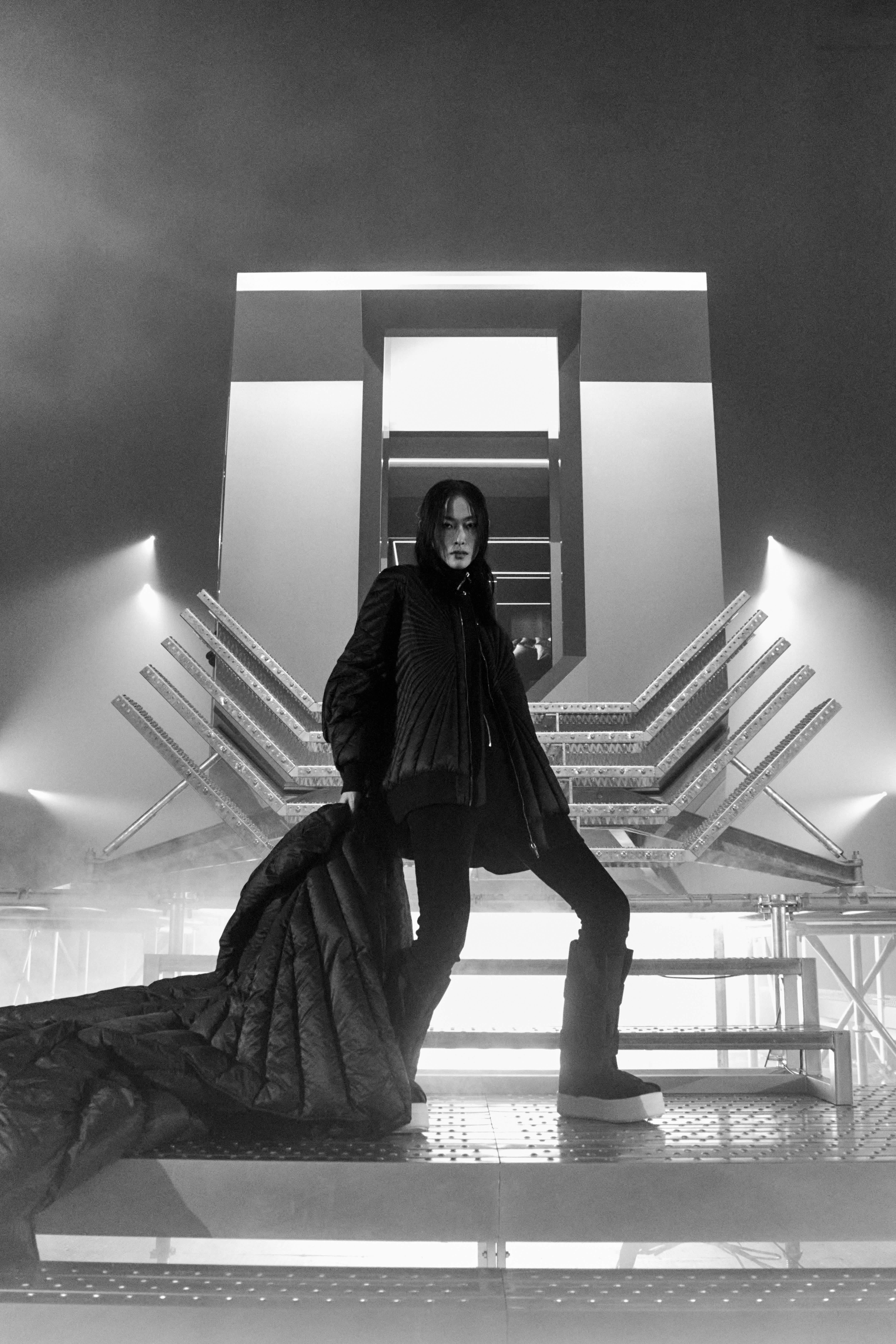

And his new collaboration with Moncler reflects these ideas. As part of Moncler’s “The City of Genius,” unveiled during Shanghai Fashion week, Owens has created a special collection including exaggerated duvet jackets that act as both sculptural forms and personal sanctuaries—akin to wearable cocoons that function as shields from the outside world. The garments serve as functional pieces of art, merging utility with artistry and theory, and offering a sense of safety wherever one may go.

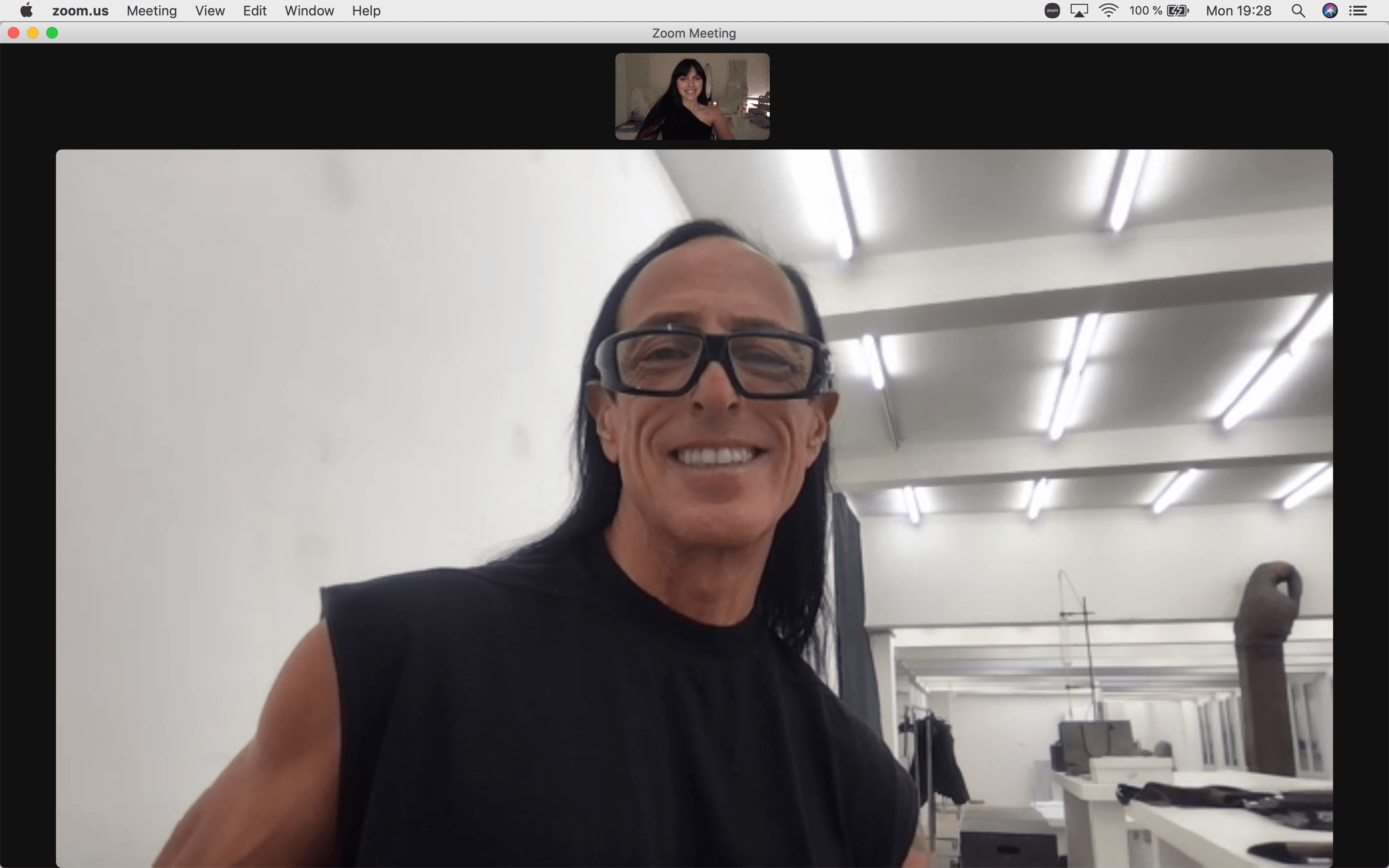

SHELLY REICH: How did this collaboration with Moncler come together?

RICK OWENS: Well, I do like the functional and the industrial. When I make clothes, it’s about technically putting them together. And what I liked about Moncler is that it was very utilitarian, but they’ve turned it into an example of art patronage. They have supported creativity in such a magnificent way. It is very admirable. I felt a connection with them because I often work with duvet-like shapes. The duvet is the easiest way to bring a sculptural silhouette into anybody's life. The volume of a duvet jacket can be exaggerated or distorted, but anybody from the Midwest to New York can relate to a nylon duvet jacket. I have used nylon duvet jackets for a long time as an excuse to exaggerate the human form as much as I possibly can.

When Remo Ruffini first approached me, I thought, I’ll do a project that I was going to do anyway. I was planning on customizing a tour bus to visit my parents in California so that I could protect this little aesthetic bubble as much as possible because I’m not that crazy about traveling.

I was also inspired by my first art hero, Joseph Beuys and his performance I Like America and America Likes Me. Beuys had a shamanistic reputation. The legend was that he had been shot down in the war and had almost died, but was by saved Tatar tribesmen and nursed to health by being covered in fat and felt blankets, and that’s how he survived this crash. That sense of insulation has become part of his mythology and that safety and protection was also part of his experience for the performance with the wild coyote. Once he was with the coyote, it became about the interaction between man and nature in a protected space for spiritual study and aspiration.

When I was 17, this was the most romantic, glamorous, moving art that I’d ever encountered, and it has always stayed with me. This whole thing about me going to the United States to visit my parents, it was very similar in a way, and I totally lifted it from Beuys. I would have this protected cocoon that was lined in felt, which became a motif that I kept going back to over and over again. And I still do. Every collection has some felt in it.

SR: Your recent Moncler collaboration includes a demountable mountain refuge. How did the idea for this refuge evolve?

RO: I’m not even sure why I was thinking of getting a place in New York. I don’t love New York because I feel this constant energy of artificial stimulation. Everyone is busy getting to where they need to be in the VIP room of the United States. But, you know, there’s performance, there are museums, there’s art, you can have your own New York. I was thinking about getting an apartment there, and I thought, how can I deal with that energy and with all the construction and buzz all the time? I'm used to the quietness in Paris. I live in the center, but the building is completely quiet, it feels like the countryside of Paris.

This was another thing I was going to work on, and it was this great extension of the previous project with Moncler, the protected bed. It’s soundproof, so that means it needs a ventilation system so you don't die. It's beautiful and glamorous, but also threatening because it's kind of a little bit dangerous and a little bit creepy. It’s a spaceship, a bed, a casket, or a tomb—it's all of those things wrapped up together.

When I think of Moncler, I think of duvet and insulation. The bus made me think of insulation and protection. The bed was about insulation, isolation, and protection, so this felt like the right path for me to follow. Then for this project, I decided to do a refuge, and I was thinking of my wife Michèle Lamy, whose family has had a refuge for skiing in Les Arcs for a long time.

Skiing…duvet…Moncler—there was a connection—but what’s more is that they have a refuge that was designed by Charlotte Perriand. So, I thought, I’m going to do a demountable house that is inspired by Charlotte Perriand and Jean Prouvé, who is known for having done a lot of demountable houses.

It’s the same thing; it is another stainless-steel sculpture reminiscent of a tomb, a casket, a spaceship, and a refuge. It’s lined in felt and Moncler duvet, and it has a wardrobe that coordinates with it. And it followed the progression of the tour bus and the protective, soundproof bed, as it was another protective, insulated environment. I like the idea that my projects with Moncler have their own language and narrative.

SR: In your work with Moncler, how do you connect this performative aspect to a brand known for its utilitarian nature?

RO: Well, when I first started making clothes, the thing that I resented most about fashion was when male designers would push women out onto a runway in these fantastic, parade clothes, and then they would come out at the end in jeans and a t shirt, as if to say, what I’ve presented is a fantasy that is only suitable for a fantasy occasion, not for real life. When I decided to make clothes, I told myself, I want fantasy to be part of every day. I want every day to be a special day. I don’t want to be making clothes that are reserved for red carpets only. I want to make red carpet clothes that you can wear in the day. So, I was making gowns with fishtail trains, but in gray wool that you could wear with flat shoes during the day. I was trying to bring that kind of theatrical, dramatic fashion into everyday life, because I wanted somebody to be able to be that work of art all day long every day. I didn’t want there to be a separation. I wanted to corrupt the banality of everyday life with the glamor and theater of radical fashion––I wanted to blend them in.

That’s how I think about runway shows, too. People have asked in the past if runway shows are obsolete, and I really don’t think they are. They might take other forms, but the idea of people gathering together to share a moment of transcendent beauty is something that has been going on since the Stone Age and will continue forever. For people to have a community experience like that—that’s what we’re on Earth for. That is communication, bonding, uniting—and fashion shows are that. Going to church is that, going to heavy metal concerts is that, sports events is that, and all with their own fashion and their own uniforms and their own codes that people are wearing to communicate with each other; all of those places have their own codes of fashion. When I’m selling clothes, I think of my clothes as relics of those kinds of ceremonies. When people buy my clothes—for example, when they buy a simple black skirt—they’re buying a skirt, yes, but they’re also buying the memory of everything that I have expressed and the values that I promote.

SR: I was also thinking about the role of rituals in your work, as this motif seems to appear often throughout your practice. What is the process behind your fashion shows?

RO: When I started out, I never planned on doing runway shows, as I didn’t think that I would get that far. I just thought that I would do eccentric clothes that would be like a little footnote of fashion somewhere on Hollywood Boulevard in LA. The only reason I started doing runway shows was that, at the time, American Vogue wanted to promote American designers, and they said, “We’ll put on a fashion show for you if you want.” At first, I was really hesitant because I thought, well, maybe I could do one fashion show.

Then I thought, “Well, fuck it, I’m 40 now, and I’ll always wonder if I decline. I’ll always wonder if I did the right thing. So why not? What the hell.” So, I started, even though I had never been to a runway show—I really didn’t know what I was doing. It took me a while. I was kind of awkward, and it took time to gain confidence in how I presented things. But then, after a while, I started having fun and gained enough confidence that we weren’t going out of business. And so, somehow, as the shows started, I was able to loosen up and express myself more with them.

And one of the things that I was thinking was, when we talk about beauty, runway shows are ceremonies of beauty––so how can I talk about beautiful behavior as well as physical beauty and beauty in physical presentation? How can I tie it all together? And I feel that that’s when I was able to start doing these ceremonies in a way that brought those subjects up.

SR: Considering your focus on anti-beauty in your work, how do you see these elements challenging traditional notions of beauty on the runway?

RO: The thing about beauty was something I resented at the beginning, male designers wearing jeans and t-shirts while they presented women in these fantastic fantasies. And I knew that I didn’t want to do that. I knew that I wanted to be what I wanted to be, what I showed on the runway. I wanted to represent it myself every day. I wanted to be honest. I wanted to really commit and live what I was showing. I promised myself that I would never put anything on a runway that wasn’t for sale, no matter how ridiculous or outlandish. A sense of humor is the most elegant, chic thing in the world. And clothes for me are the most fun when they veer towards ridiculous. There is a witch and a devil-may-care attitude about that. There’s a bit of lighthearted mockery of tradition that I like to introduce whenever I can.

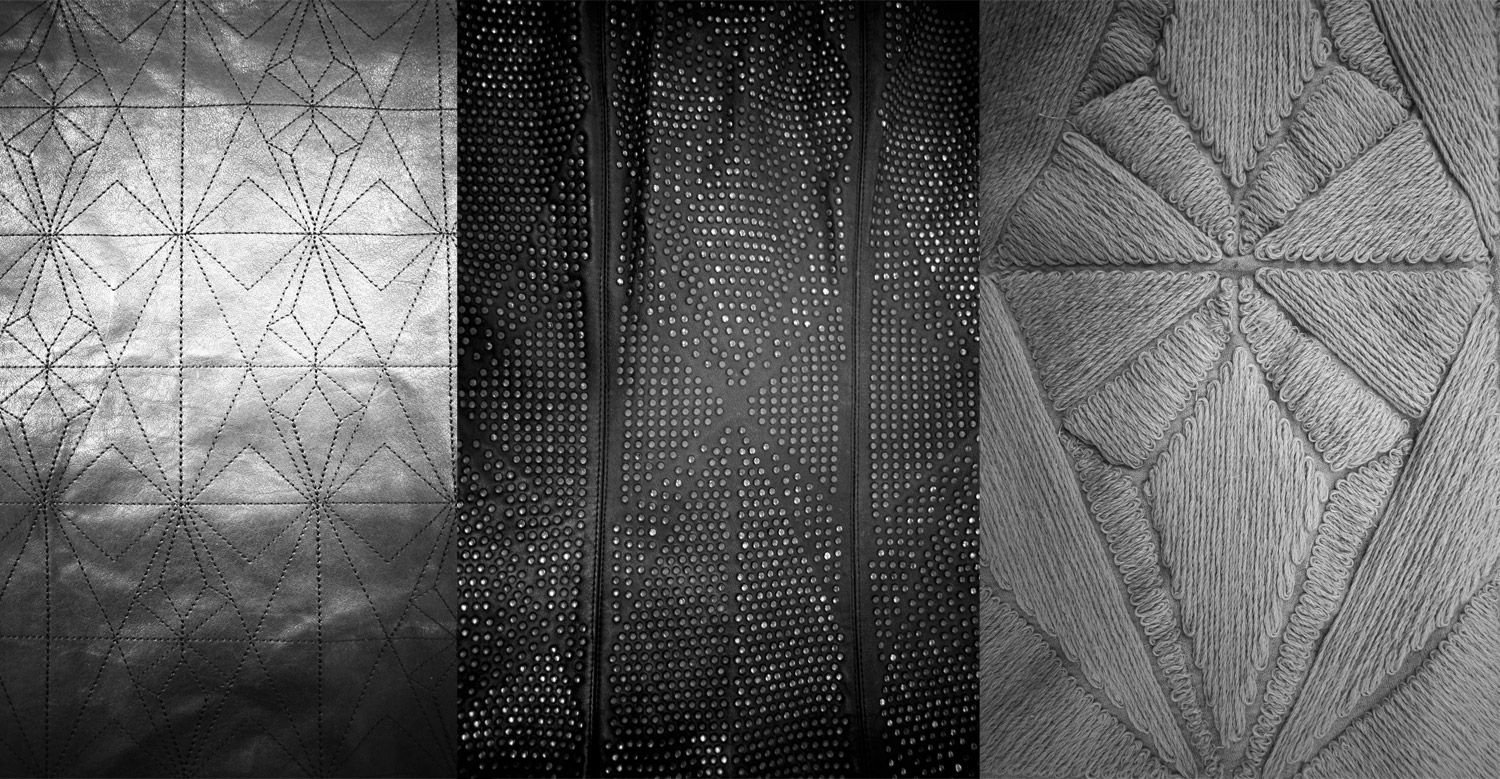

Also, I love the idea of grotesque artifice. When I first started becoming aesthetically aware, my dad had a lot of Japanese art books in the house because he developed a fascination with Japan after serving in the war. There were these beautiful books of old samurai watercolors, and I remember first seeing Onagadori roosters in the watercolors. Onagadori roosters were bred during the samurai period of Japan to produce these really long tail feathers that were like two meters long. These feathers were so extreme, and the idea of breeding these roosters just to have these decorative feathers was so artificial, controlling, perverse, beautiful, and exquisite. That was one of my first examples of something that was almost grotesque and perverse—that amount of effort and profound manipulation.

And then there were Japanese ceremonial robes and court robes that were so perverse. Every example I had seen of femininity had been a princess with a tiny waist in a Disney movie. The extravagant disregard for what would be normal and traditionally attractive, and making that volume grotesque was, I thought, so chic and clever and, yeah, so Kabuki. When people say my stuff is weird and the proportions are odd, I’m like, did you study history? I mean, bustles and panniers—we don’t do anything close to that. In comparison to those artificial devices, we are the safest generation ever.

SR: Building on the idea of viewer perception, which is often considered a cliché yet remains a fundamental question, do you believe that art or fashion can exist meaningfully without a viewer?

RO: No, it's a conversation. I’m working on a retrospective right now. I had one in Milan ten years ago, and now I have one in Paris. And this is incredible. Not everybody is able, in their lifetime, to define what they want their life to be presented as and to be able to write their own obituary or their own life story exactly the way they want it presented. Most of our lives, we are searching for validation. I’m not saying that in a critical way, but a huge part of our life is wanting to be understood by our partner or family.

I’ve always thought that I had poor social skills because, when I was young, I was an only child, and I didn’t know how to interact with other kids. I never played sports or got involved in school clubs or anything. So I never learned how to be with a group of people, how much energy to absorb, and how much energy to block. I always felt like interacting with people was not my comfort zone, and I always knew that.

But when I was doing this retrospective ten years ago, I was thinking, I was put on earth to communicate. I was able to communicate; I was able to get validation in a much bigger way than I ever dreamed of. And this changes a person. When you have that amount of validation, I don't know if it changes everybody, but for me, I’m thinking I’ve gotten more validation than I ever dreamed of, and I’m so grateful and satisfied with that because what I do is my form of communication. This was my way to participate in the world, my way to connect with people. So I needed the viewer. I needed the response.

SR: In what ways is your concept of anti-beauty reflected in your collaborations, and how does this idea connect to your personal identity?

RO: What’s great is that when I collaborate with brands, we work together to produce things that are more responsible. Sometimes I use collaboration as an excuse for both of us to find new ways to work. When I started my company, I bought the company that had agreed to license me years ago. I inherited a way of working that we gradually had to improve and change regarding sustainability and ecological responsibility.

As I got older, I became more confident in who I was. For a while, I wasn’t sure that my identity was established enough to distort it with the inclusion of another name. I needed to define myself first. Then, I decided I had defined myself enough to be prepared to go out and play with people. It was a new way of playing, and a way for me to meet people and see how others work. It became a creative challenge, and I didn’t feel like it would compromise who I was.

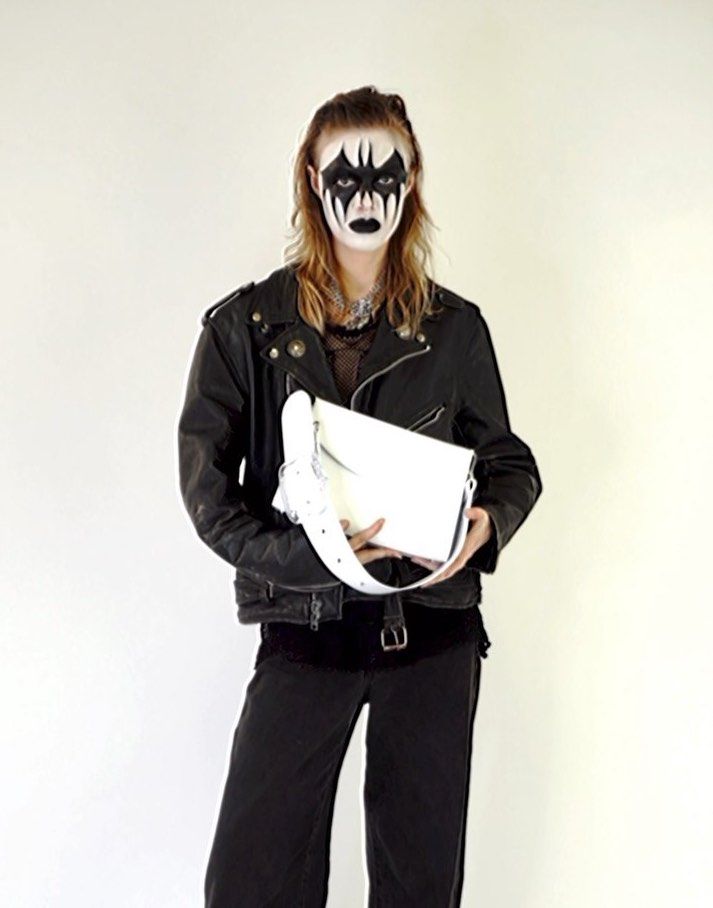

After a while, I felt like I had to present a project that I wanted to be about alternative aesthetics. There is something I call “airport aesthetics.” When you go through an airport, you’re obliged to walk through the perfume section. You’re herded, and there’s no way of avoiding it. It all looks the same all over the world, and this has been established as our global definition of aesthetics, beauty, and aspiration. I resent that kind of narrow view because not everyone can see themselves reflected in it. I want to be the guy who says you can be a freak and celebrate that. You can be a mad eccentric, define your own beauty, and find confidence in that. There is a history of alternative eccentric beauties that never fit the mold. When I was young, I had John Waters, the Rocky Horror Picture Show, David Bowie, Divine, and Lee Bowery. I had my pantheon of people promoting an aesthetic that was thrilling and alternative to what was considered good taste. Like I always say, bad taste is timeless.

I tried to create an alternative aesthetic, that didn’t reject the airport aesthetic because it is attractive and valid. I don’t want to burn it [the airport aesthetic] down. So, I tried to create this niche, however, the people in this niche sometimes seemed to create a wall and protect it, saying, “No outsiders allowed.” It became something that people didn’t feel like they wanted to penetrate—“Oh, the Rick Owens world. That’s the Rick Owens’ world. That’s not my world.” What I had started out trying to do as inclusively as possible ended up being this fortress that others weren’t allowed into.

That was one of the reasons for the collaborations: to say, “Hey, I’m friendly, you’re not rejected.” I wanted to show that anybody could join. It was a way of getting out of my niche and spreading my values into the world.

The other thing is, I use pentagrams a lot, and when people go off on how satanic I am like, that’s exactly the conservative value system I am battling—the ones that are condemning and judging. To me, a pentagram is a symbol of otherness and queerness. Also, Satanism has been a tool that culture has used to condemn outsiders for a long time, such as witch burning.

I use the pentagram as this cheerful little heckle to disturb conservatives. I love being able to put that on my collaborations because that’s what I want to represent: tolerance and a welcoming place for otherness, flexibility of aesthetics, and tolerance of aesthetics.

Credits

- Text: SHELLY REICH

Related Content

The Zone

All Networks Lead Through Kansas: The Shadowy Well(ness) of Masculinity

Reinventing Mike Kelley

Brenda’s Business with RICK OWENS

Petra Collins Says Sorry

From Rags to Rags: RICK OWENS Inside Out

Fakethias’ Infinite Horizon

Mire Lee’s Fountain of Filth

The Opioid Crisis Lookbook: An Interview with DASHA ZAHAROVA and DUSTIN CAUCHI

Productive Narcissism

The Politics of Beauty: Tyler Mitchell

Charles Jeffrey LOVERBOY’s Utopian Fantasy