A Gateway to Forbidden Realms: Rob Kulísek

|SHELLY REICH

The world of photographer Rob Kulísek was shaped by his evangelical upbringing where photography emerged not merely as a tool but as a medium of liberation, a gateway to voyeuristically explore “forbidden” realms.

Now operating between fashion photography and art, Kulísek deftly navigates their complex interplay and shows that the most compelling narratives reside in the liminal spaces between, where boundaries blur and where labels dissolve.

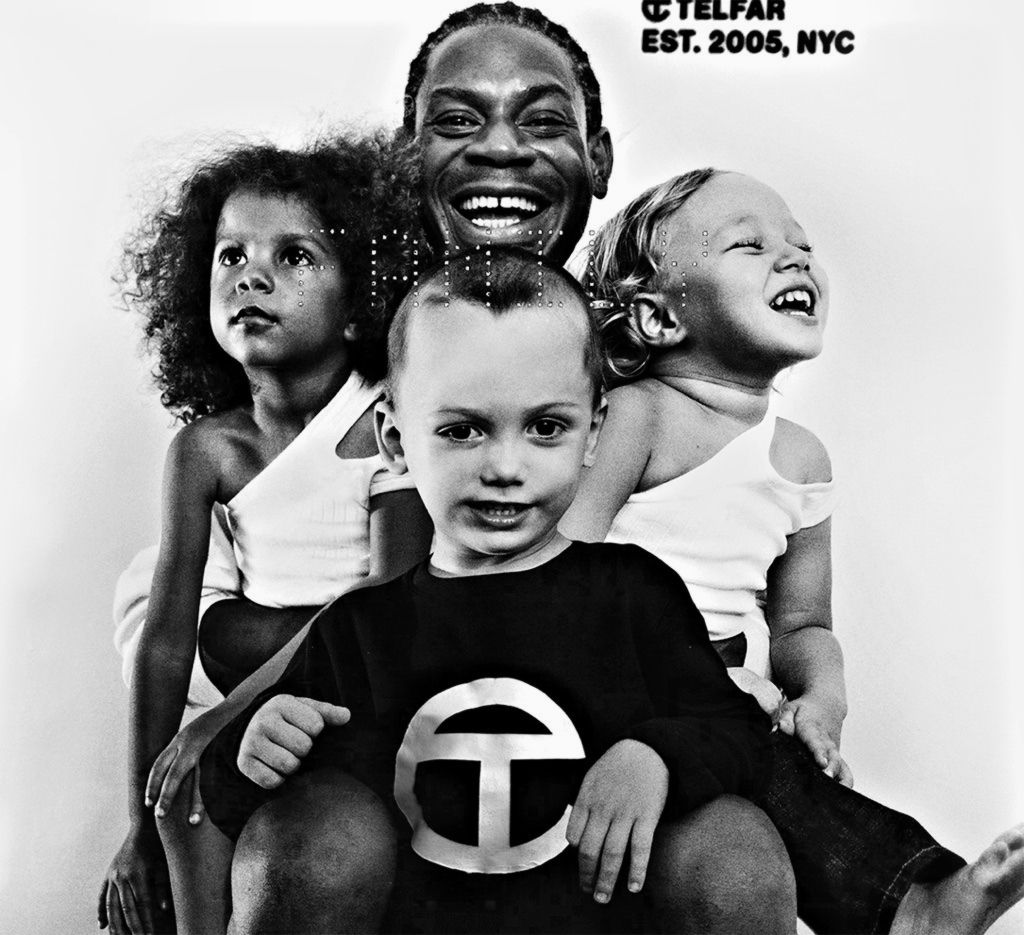

Running throughout Kulísek’s work is a strong ethos of collaboration. Together with David Lieske, he unveiled a series of fictive magazine covers at Liste Art Fair Basel in 2016, which gave a glimpse into the kaleidoscopic world of their artistic vision. This endeavor birthed 299 792 458 m/s, a magazine named after the speed of light, which emphasized the symbiotic relationship between art directors, stylists, set designers, and other creatives in the alchemy of image making.

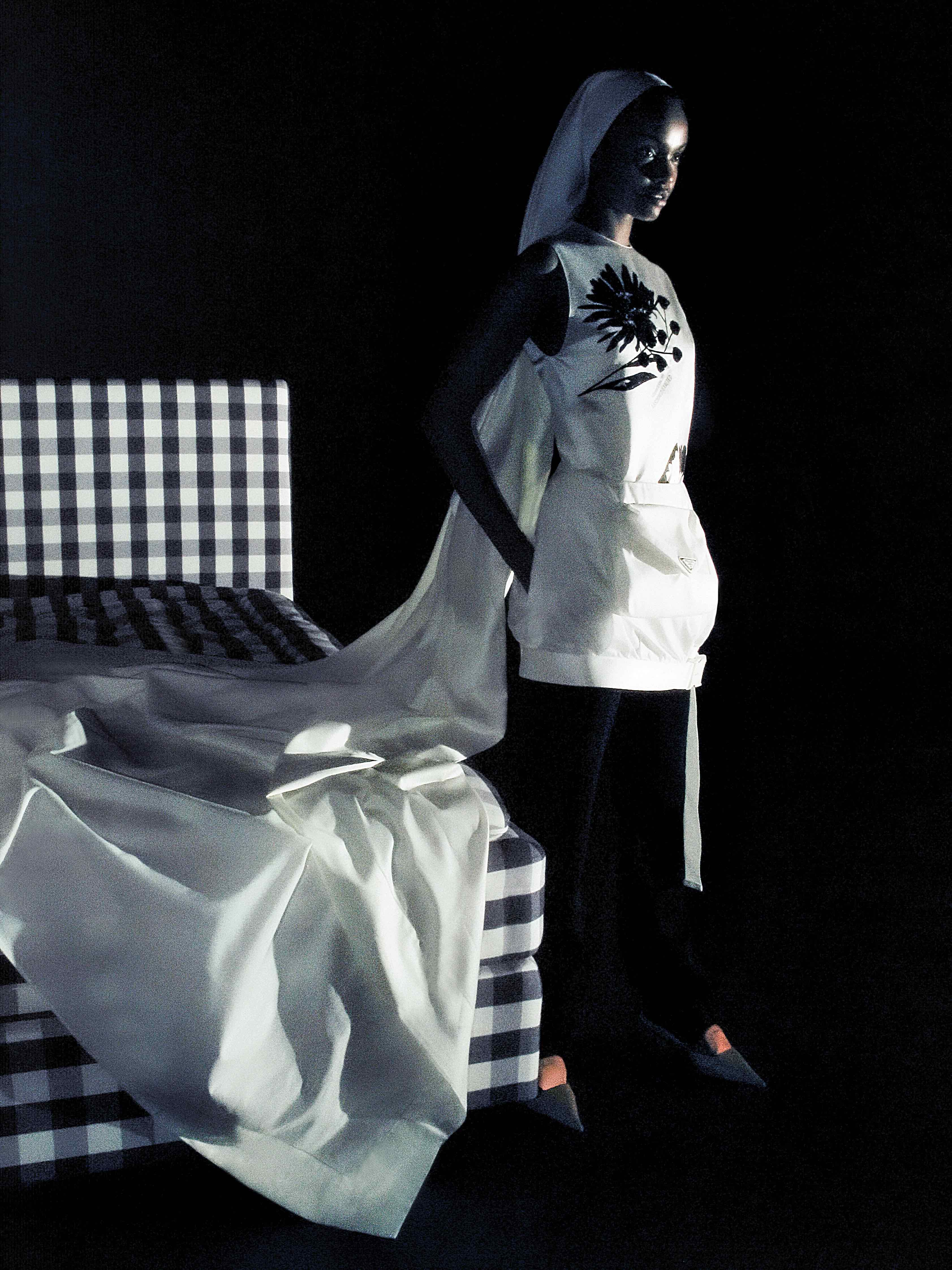

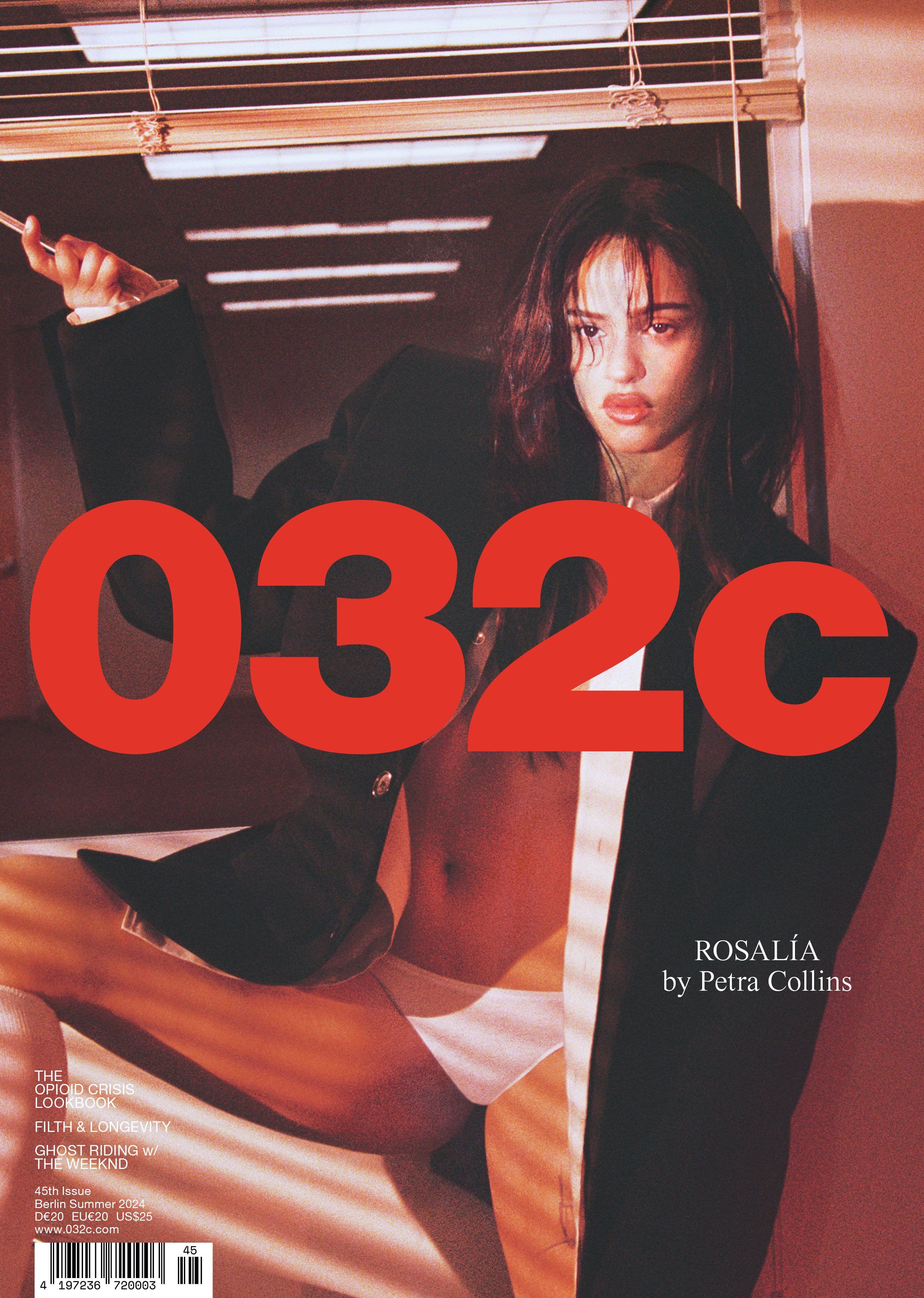

In 2023, Kulísek exhibited his investigation of Paracelsus—an enigmatic, ultra-luxury rehabilitation center nestled on Lake Zurich—at the Oslo gallery VI, VII. The photo series—which was produced upon the invitation of curators Charles Teyssou and Pierre-Alexandre Mateos to contribute to an issue of The Opioid Crisis Lookbook, who are the authors of our Issue #45 dossier—captured the ebullient Meg Yates, aka “Meg Superstar Princess,” a New York socialite and internet personality who openly addresses her eating disorder and mental health issues, posing at the Paracelsus estates. Blending surrealism with the starkness of truth—Meg has never been a Paracelsus patient, Kulisek photoshopped the images—the series is charged with an uncanny energy. Yates, an internet sensation for chronicling her battles with unflinching honesty, has also proven to be a kindred spirit whose journey mirrors Kulísek’s own quest for authenticity amidst the artifice of the world.

SHELLY REICH: How do you view the relationship between your art and fashion photography?

ROB KULISEK: Well, I’m not often thinking art versus fashion these days, although I used to obsess over these labels early on. On a practical level, having both practices work alongside each other is nice because art operates much more slowly, and in fashion, of course, it’s usually more frenetic and immediate. I enjoy this balance of different flows.

Growing up in a conservative and evangelical household, I found photography to be a way to visualize things I was interested in but couldn’t openly engage with, a voyeuristic way of exploring forbidden topics. My work, whether for a fashion campaign or for an exhibition, always tries to use image-making to address topics often hidden or repressed in the mainstream.

When I started working in fashion, incorporating similar logics that I was beginning to define in my art practice just felt natural. And, of course, this is nothing new, dating back to the surrealists such as Man Ray, Wols, and Lee Miller who used fashion assignments to leverage their experimentations in the studio.

The biggest difference between creating fashion images and the intimate nature of making art on my own is the emphasis on teamwork in the commercial realm. Collaborative innovation is key, and I thrive on that interplay. There are often serendipitous moments where ideas bounce off a team of art directors, stylists, set designers, graphic designers, all bringing their unique perspectives to making the final assets. Some of my best work has been made alongside art directors including Eric Wrenn, Babak Radboy, and Alexia Cayre, who in different ways manage to know when to give me freedom and when to reel me in, so to speak. This collision of ideas and a particular art director’s signature ways of editing a selection of images into something that’s both legible and provocative excites me and opens doors to creations I wouldn’t necessarily envision on my own.

SR: Collaborations seem to be a significant aspect of your practice, whether through exhibitions, installations, or magazines. One of your more prominent collaborations is with David Lieske on the magazine 299 792 458 m/s. Can you share more about how this collaboration came together?

RK: I met David in Los Angeles in 2014, and he’s been my biggest source of inspiration, a mentor and partner since then. We are total opposites in many respects, but it’s the clash of our perspectives and methodologies while collaborating that has led to some unpredictable yet exciting outcomes. Our first collaboration began while I was at the Mountain School in LA in 2014, where we started an atmospheric black metal project called Misanthrope CA. This led us to curate an exhibition looking into the aesthetics and symbolism of misanthropy and nihilism and that was when we first started making art collaboratively.

In 2016, we presented together at Liste Art Basel with our gallery VI, VII, where we created fictive magazine covers from images shot while recording our album in East Hampton. Our collectors Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner were so moved by these that they encouraged us to go deeper into this, leading to 299 792 458 m/s—a magazine named after the speed of light in meters per second, a nod to our desire to traverse topics and themes in fashion with the same boundless velocity. We published two issues, The American Issue in 2016, and The Overworked Body Issue in 2018, to much acclaim.

After a hiatus, we are excitedly working on a third issue, set for a September release with events planned in Berlin, Paris, and NYC. This next edition remains under wraps, but it promises to continue our exploration of fashion photography’s desire to capture, convey, and expose, or conceal.

SR: Where do you see yourself in terms of identity? Do you consider yourself primarily an artist or a fashion photographer?

RK: When I moved to New York, I was originally studying biology and pre-med with the goal of becoming an osteopath. At the same time, I was really into surfing and spent most weekends on Long Island. One day in Montauk, I met Shannon Simon, Taryn Simon’s sister and then studio manager. They had just begun working on Taryn’s epic project A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters, which explored societal narratives through bloodlines, migration, and political upheaval. This chance meeting led to an internship at her studio, which I managed to get approved for credit because it had a biology angle. I quickly realized I wasn’t cut out to be a doctor and dropped out of school to become a researcher in her studio for two years. I never looked back.

Early on, I started brooding about these labels like “fashion photographer” versus “artist” because, during the time I was working for Taryn, she decided to stop taking on commissions for magazines or fashion brands. This felt a bit sad to me since some of her early work, such as campaigns for Chloé and Cesare Paciotti, are still some of the most impactful and beautiful images I’ve ever seen and left an indelible mark. Yet for her, the seriousness of art with a capital A took over the perhaps superficial yet still conceptually rich world of commercial image making.

I grew to define my stance on this and found that labeling oneself in these binaries doesn’t really capture the fluidity of what we do today. I think the most exciting work exists in the spaces between these categories. And by embracing this in-between space, I can challenge the norms of both fields and see these labels not as final end points but as part of a larger, more dynamic conversation.

SR: Your work draws inspiration from independent fashion press from the 1990s, such as Purple and Self Service, as well as fashion brands including BLESS. How do these influences manifest in your photography?

RK: The printed form has always been the fundamental source of inspiration for me, not in a static sense but as a vibrant part of today’s image economy and mapping how ideas recirculate and have the potential for reinvention. Surf and skate culture ephemera and films as well as very niche early gay porn and other erotica were incredibly inspiring and formative, especially growing up in a family of conservative newspaper publishers.

Regarding fashion magazines, yes—the 1990s were marked by a unique freedom and abundance of resources. The ones you mentioned pioneered what fashion magazines could be, creating a new visual language that blurred the boundaries between fashion and art, emphasizing the photographic narrative over the garments themselves.

As for my relationship with BLESS, this is something that I treasure and am, of course, honored to be an ongoing part of. It’s one of those situations where your favorite artists become your friends, from inspiration to direct collaboration. I have been working closely with Ines and Desiree for years now, photographing lookbooks and special projects when scheduling allows. During Covid-19, I lived in the studio above their shop in Paris for a time and they gave me access to their archives and asked me to create an index of almost all of their past objects and garments. It’s rewarding to work with a brand like BLESS, who still treasures the printed object and the physicality of fashion at its core.

SR: Your exhibition “Meg at Paracelsus” at VI, VII in Oslo showcased Meg Yates’ portraits set against the opulent backdrop of a 100,000-Dollar-a-week rehab facility [Paracelsus]. Meg, a quintessential New York icon, exudes a vibe reminiscent of Courtney Love and the facility’s ambiance draws from the spiritual beliefs of C. G. Jung. How did this collaboration with Meg unfold, and what inspired you to shoot her portraits within the context of the rehab facility?

RK: The curators Charles Teyssou and Pierre-Alexandre Mateos invited me to explore Paracelsus for the first issue of The Opioid Crisis Lookbook that they were co-curating. The facility, shrouded in secrecy, caters to elite clients near C.G. Jung’s former home overlooking Lake Zurich in a tiny enclave called Küsnacht. Having grown up with several family members with substance abuse issues, I was aware of Jung’s spiritual approach to recovery and its influence on the “12 Step Program” from an early age. Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious—which emphasizes shared human experiences, communal healing, and a spiritual understanding of life—stands in stark contrast to the exclusive, individualized treatment model at Paracelsus. There, patients reside in private villas with a personal staff of twelve, including orthomolecularists [who practice an alternative form of medicine that claims to maintain health through nutritional supplementation], nutritionists, a live-in chef, and personal trainers, underscoring the isolation and exclusivity of their recovery process.

Meg Superstar Princess—as she is more widely known—was already a friend after meeting her on set when she was an assistant for a few stylists that I worked with regularly. She quickly grew into her own and became this internet sensation with her raw and unapologetic blog, lehipsterportal.blogspot.com, where she chronicled her battles with an eating disorder alongside wildly creative daily fit pics and frenetic coverage of her relapses and rabbit holes.

We first worked together officially during the first year of Covid-19. I had to shoot a lookbook for Rosetta Getty, which was art-directed by Jordan Richmond, but due to travel restrictions, I was unable to be there in person. I somehow thought Meg would be the perfect camera operator, so I pitched her to Jordan, he accepted, and I bought her the same point-and-shoot camera that I normally use and oversaw the shoot via Zoom but mostly let her do her thing. For me, the lynchpin is always in the editing, and I do this in a very personal way, so there were no questions of authorship—she was down to create material or, let’s say, “data” for me to then dive into and mine. Everyone at that time seemed to be frantically searching for ways to work remotely, but this relationship instantly felt very synergistic.

This project for OCL came about shortly after, and I decided to approach it in a similar way. Meg helped catalyze this new wave of indie sleaze that has taken over NYC, and so the prompt was for her to create a series of looks that she might bring to Paracelsus if she were admitted there.I’m sure most patients show up with trunks full of Loro Piana and Malo, but Meg would arrive with wet fur, a damaged Chanel matelassé, and a t-shirt that reads “JIZZ.” I provided a few guidelines for poses to help with the compositions I had in mind but mostly gave her the freedom to capture self-portraits as she wished.

The real alchemy happened when I overlaid her intense, almost deranged and inebriated self-portraits onto the eerie headshots of the Paracelsus staff that I pulled from the facility’s website. The resulting images became these palimpsests charged with an uncanny and surreal energy. The layering created a tension that felt spontaneous yet deeply intentional.

The entire process was an experiment with chance, leaning into the unexpected and allowing intuition to guide, and trusting the beauty that can be found in the unpredictable nature of image making.

It took me a while to trust myself enough to allow chance so much autonomy in my work, and I’m still learning to do that, especially in fashion, where there are so many expectations and variables at hand.

SR: What kind of expectations? Attending Fashion Week, for example?

RK: Well, I don’t have to tell you—the politics of the fashion industry are very intricate. Sure, there’s the pressure to be social and show up, which is fine—I like to have fun. But it’s more the expectations that the industry sets for how a photographer’s output should be situated or adapt based on hierarchies, technological evolutions, trends, etc. Who one chooses to work with and where one lets their work be seen. To make it in this industry, one has to be quite calculated, which can often detract from the work itself.

I’ve learned to be comfortable with letting things unfold organically and nurture longstanding relationships rather than jockey for position. This way, the work can remain genuine and, at least I would hope, avoid becoming a mere commodity.

SR: And so what’s next?

RK: There are lots of exciting things. I was living between Berlin and Paris mostly for the last four years, but over the winter I was commissioned by a new real estate concept project called Home0001, led by Christopher Kulendran Thomas and Annika Kuhlmann, to create a body of work inside their new development in the Lower East Side. This is the first of six locations they are developing in cities around the world, and the goal is that it becomes this network where you can own one home and stay for free in their other locations.

Anyway, they proposed that I spend a few months living there to create a full spectrum of images for their campaign. So, I’ve been splitting my time between one of the units at Home0001 and Cape May, New Jersey (where I grew up) living on this 1980s boat that I restored over the winter. I really missed nature and serenity and here I have plenty of that.

I’ll be traveling back to Europe in June for a few campaigns and editorials and also preparing for a museum show in Norway at Stavanger Secession, curated by Charles and Pierre. Then, there’s this children’s book with pictures of Hermann Nitsch, the Persian cat I share with my flatmate in Paris, that Westreich Wagner wants to publish in the fall. And then—this is the best part about being in the fashion industry—everyone is OOO in July and August [laughs].

Credits

- Text: SHELLY REICH

Related Content

Setting Horses On Fire with Jordan Hemingway

032c Issue #45 “The Opioid Crisis Lookbook” Summer 2024

Old Town Fury Road: LIL NAS X, “Daddy Lessons,” and the Black Yeehaw Agenda

Art World Resorts: A Remedy for Chronic Anxiety

Discovering the Aura with Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo)

The Future of Couture: Neo-digital natives, blockchain luxury, and algorithmic customization

Do We Want Anarchy Or Guerilla Warfare? Julian Klincewicz & RASSVET

Art World Resorts: artgenève