From the Sleep Side: DILLER SCOFIDIO + RENFRO

|MAHFUZ SULTAN

In an essay of fragments, filaments, and flashbacks, originally published in Issue #41, MAHFUZ SULTAN responds to the work of DILLER SCOFIDIO + RENFRO (DS+R), a New York-based design practice founded by Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio in 1981. Now comprised of a team of more than 100 architects, led alongside DS+R partners Charles Renfro and Benjamin Gilmartin, the studio's cultural and civic projects include the New York City High Line, the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, and Los Angeles' Broad museum. Diller and Scofidio were the first recipients of a MacArthur Foundation grant in their field, awarded for work that "illustrates that architecture … is everywhere, not just in buildings."

ANNE CARSON’S EARLIEST MEMORY WAS OF A DREAM. When the poet was three or four years old, she dreamed that she stood in her living room. On the surface, everything seemed normal, from the dark green furniture to the pale green wallpaper. And yet, somehow, the living room felt demented, as if faintly breathing and crouched in wait. Beneath its familiar exterior, Carson sensed a chaos that camouflaged itself in green waking life. Many years later, she came to believe that the living room itself was asleep, too, and that she had entered it from “the sleep side.” Even as a child, she intuited what the philosophers already knew: that the systems we use to organize everyday life restrain an almost uncontrollable flood of desire. I believe this moment is Anne Carson’s origin myth. This is what it means to be a poet.

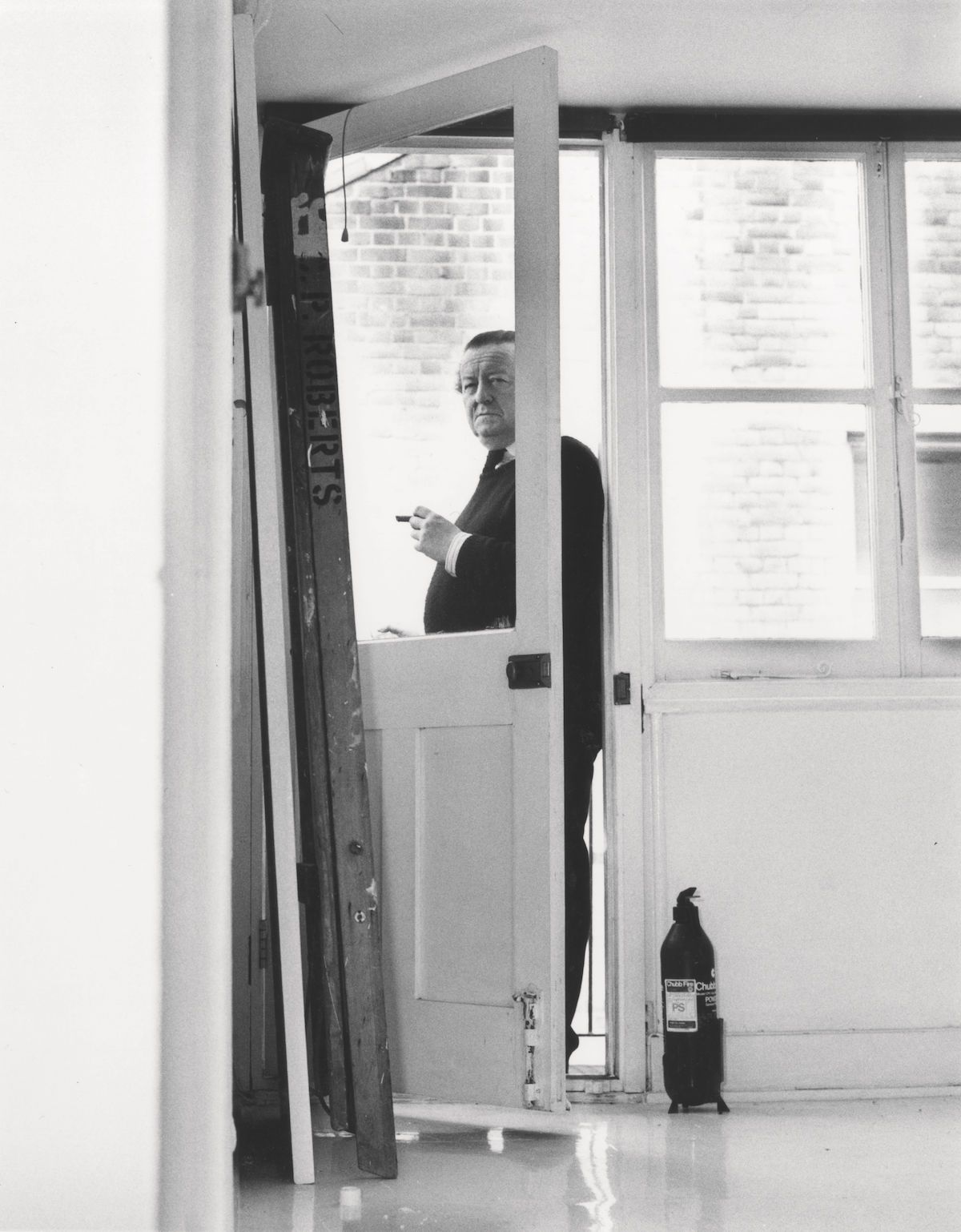

Elizabeth Diller, Ricardo Scofidio, and Charles Renfro (DS+R) entered architecture from the sleep side.

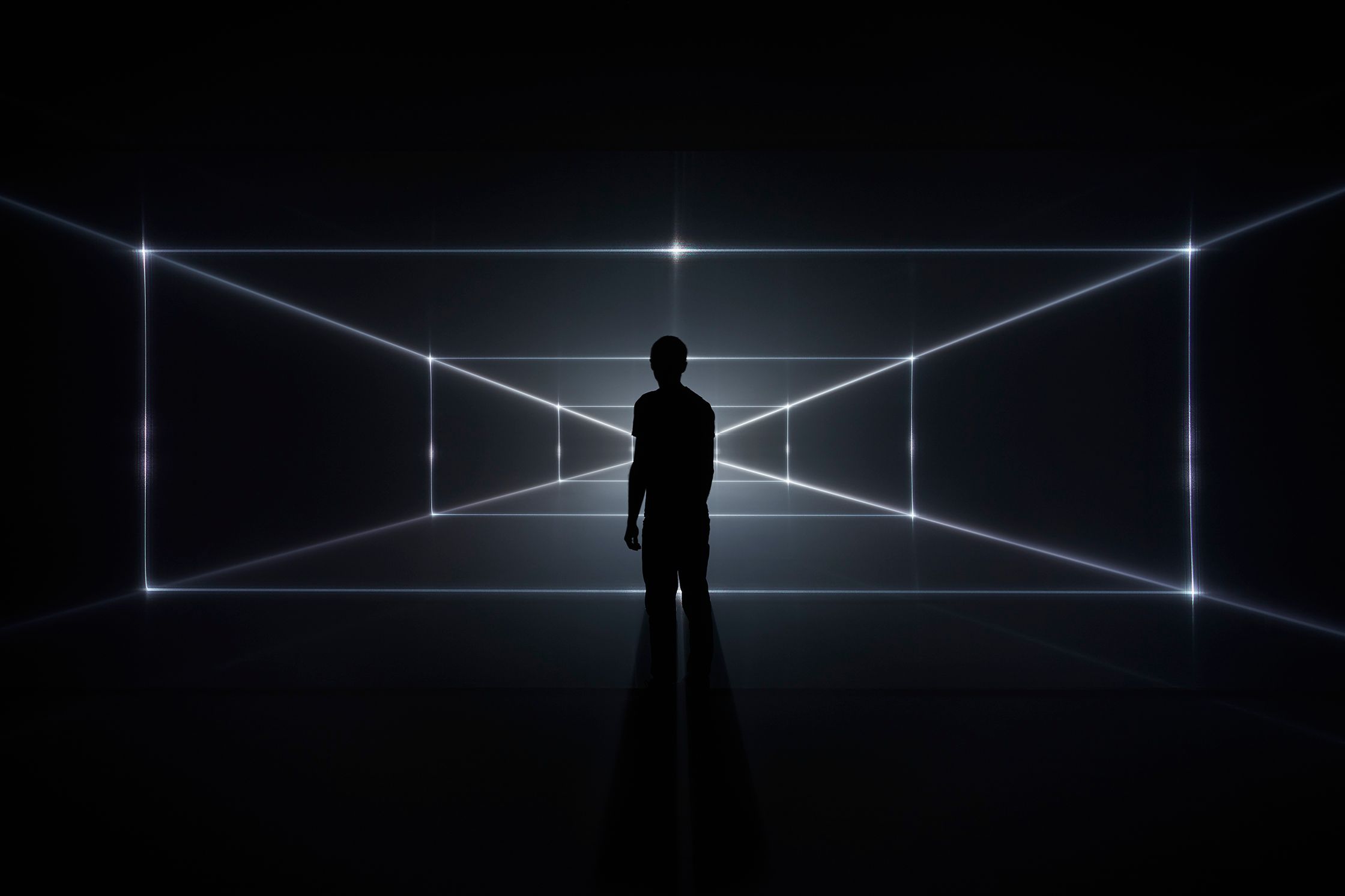

Another origin myth. Night. A glass-walled tower on Sixth Avenue sleeps. I see the wired glass of the guard doors as they swing open, then a stack of blinking CCTV units, and an x-ray machine left running. A see-through mirror frames an empty lobby in wide shot. The lights overhead glow in the polished marble floors. They refract in the banks of revolving doors and bounce off the wall of brass plaques. The periodic beep of an alarm panel echoes through the lobby from somewhere out of frame.

Now, an elevator – metal, cold, yet another mirror. Then, upstairs, the hallways empty and humming with lights. There are fields of monitors and televisions and windows where the reflection of the room and the blur of the city double into a single image, and this tower is just one slick black mirror in a landscape of hundreds.

Every surface is a screen or mirror or both. All day and all night we watch one another, and when we sleep, the buildings go on looking without us, in an endless relay of reflections.

In Travelogues (2001), DS+R installed 33 screens, evenly spaced along the 1,800 linear feet of corridors between the arrival gates and passport control at Kennedy Airport in New York. The screens flashed x-ray images of travelers' suitcases as they passed, in a time lapse sequence created by the spaces between screens. The suitcases were portraits of their carriers, and a surveillance technique became a cinematic gesture.

Of course, to view the work without actually flying into JFK, one must have gone through customs and passport control in reverse. Walking through a security apparatus against the grain allows for a different kind of sight. One enters the theater from backstage and catches the building with its back turned.

Several years ago, Chloe and I lived across a narrow courtyard from Lebbeus Woods, an architect of ruins in the sky and dream cities hidden in underground caverns. I still see a maquette of his, a set of fragments paused in flight, alighting at his window like a bird. Every day, we worked opposite each other, he at his window and I at mine, one man at the end of his journey and the other at the beginning. Back then, I was unaware that either of us was an architect. I knew simply that we shared the same rhythms – the same periods of intensity, the long hours, the occasional lapses into lassitude and disappearance.

The poet Etel Adnan wrote that “the square is the passion of the circle.”

She could have been talking about La Notte. She could have been talking about architecture. She could have been talking about flesh.

One winter, we converted a portion of our loft into a makeshift theater. In the mornings, I worked on an adaptation of Oedipus Rex for mime. What began as a libretto transformed, over several months, into choreographic drawings and imaginary constructions that I set the mimes to work on. In the evenings, I made drawings of Jeanne Moreau’s walking paths through Michelangelo

Antonioni’s La Notte (1961). The actor radiated a desire so sharp and intense that I tried to cut space with it. As the lines that represented her movements gave way to planes and then walls, I realized that Antonioni created a labyrinth to trap Moreau’s desire, and she was lodged in the center of it like the Minotaur.

In 2002, Diller and Scofidio designed a cloud. They called it Blur. It was a 600-square-foot elliptical platform that hovered 75 feet above Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland. Visitors wandered through it aimlessly, as though in a dream, lost in the white noise generated by 35,000 high-pressure nozzles filtering the lake into mist. They danced in the static of a television screen.

An alternative, albeit witty take on the Swiss “lake house,” Blur was a site, building, and atmosphere condensed into a single form. And it was in continuous transformation – altering itself in shape and density according to the surrounding temperature and wind direction. Diller once remarked that one could literally drink Blur. I imagine it generating a waterfall effect – the inhalation of air vaporous and thick, the sudden rush of negative ions, and the euphoria one feels in the wake of a waterfall.

Blur existed somewhere between simple atmosphere and elaborate construction, partially concealing its system of pumps and complex structure in the fog. One caught glimpses of these elements while immersed – penumbral, ghostlike, breaking the fourth wall and reminding the viewer of the machinery that sustains the illusion. I always think of screens when I see images of Blur – of the flat surfaces that present us with the magical transformation of a film production, with all the machinery it entails, into a projection. I also think of nightclubs, of the fog machines and glowing screens. We see each other in the fog as we do in the flash of a strobe light.

One night, immersed in total fog somewhere near the Jardin du Luxembourg, Adnan felt the presence of someone nearby, someone she thought she knew. She called out a man’s name and a different man answered her, one she did not know. They moved through the fog together until they found the door to her building. He became one of her best friends.

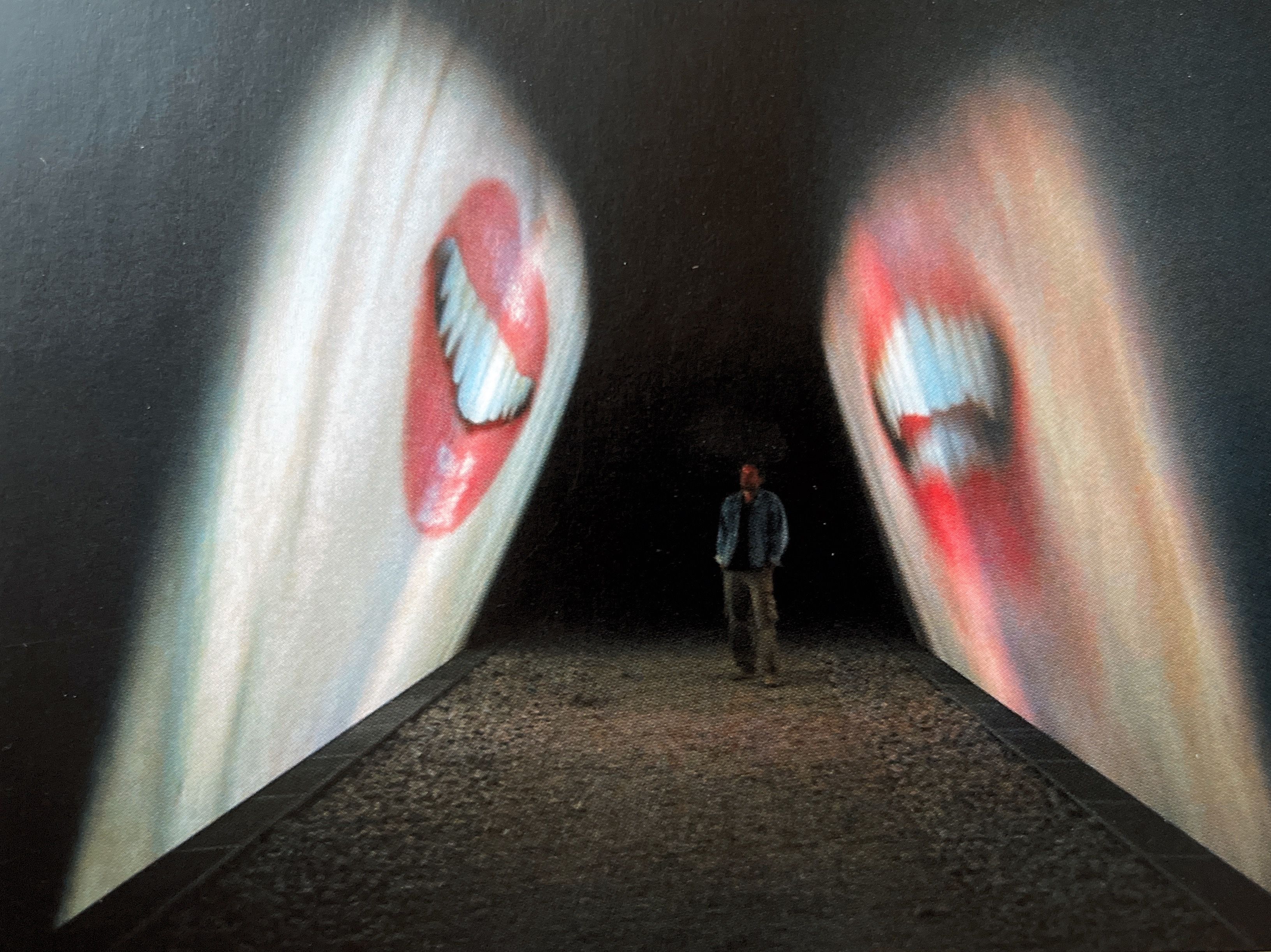

On the front cover of Diller and Scofidio’s first monograph, Flesh: Architectural Probes (1994), there is an image of Diller’s right buttock with the word “Flesh” stamped upon it. A corresponding image of Scofidio’s left buttock appears on the back cover, and the crack they share runs up the spine of the book. They meet in the very seam that holds the book together. Associating the spine of their shared imagined body with the spine of the book is not just idle wordplay. Diller and Scofidio deeply entangle the politics of space-making and surveillance with bodily discipline and control – in the literal body of a book. Flesh is organized around various body parts – the chest, eye, mouth, legs, and skin all sequenced into a succession of chapters – but arranged according to rules idiosyncratic and coded. The book is intended to be experienced rather than explained, a set of gestures more akin to an artist publication than an architecture monograph.

Every surface, even skin, is a screen or mirror or both.

Flesh is the book that other architectural monographs dream of as they collect dust on coffee tables. There is neither clear information about the practice nor a legible aesthetic program, neither captions nor explanatory language of any kind. It contains design work, found images, screenplays, transcribed dialogue, academic essays, footnotes as graffiti, and the detritus of scholarly language, each floating unmoored in a sea of pastiche. There is a system, but it remains hidden in the unconscious of the text, like the veiled structure that generates Blur. The same systems that marshal the chaos of the world into ordered units and hierarchies of value express themselves in this work as abstractions at every level, from the city to the body, even on the surface of the page. Note the total rejection of graphic design conventions in the book, the use of multiple fonts and type sizes across a single page. On some spreads, text appears to almost fall into the spine; on others, image and text obscure one another, leaving the reader with neither.

Lebbeus Woods passed away the night of Hurricane Sandy, from causes unrelated to the storm. The designer of cities made from the refuse of war and climate disaster left us during a cataclysmic event. I remember the dance of flashlights across the courtyard and the silence in our apartment. Sadly, we’d found out who he was only a few months earlier, when Nico recognized the maquette in the window and showed us a photograph of the architect. This friend is the same one who later saw my drawings of Moreau’s maze in La Notte and told me I should go to school for architecture.

A few days after Woods died, Chloe and I walked from the Battery up to my mother’s apartment on 69th at Columbus. The streets were deserted and covered with debris. I saw the High Line in the early morning light and noticed that it had sustained almost no damage. All of this exists in a single continuum to me now – Lebbeus, DS+R, and that park that settled as a marine layer over the alluvial plains of the city. In my work, I am condemned to write about Lebbeus over and over again, because I love everything that flies.

DS+R completed the last section of the High Line, a 1.5-mile-long public park built atop an abandoned, elevated railroad that winds its way from the Meatpacking District to the Hudson Yards, some 20 blocks uptown, in 2019. The High Line is a vision of a post-apocalyptic park that has grown itself out of the rust and bone of some great upheaval. Seen from above, it reads as a tributary of the Hudson River, a path cut through a forest toward water.

As in Travelogues and Blur, the High Line is a promenade for cinematic experience. It is also a refusal of naive, sentimental views – there are neither wide vistas on the Hudson River nor panoramic views of the city skyline. The park reveals the city through medium shots of surrounding architecture and long shots down city corridors that deposit themselves into vanishing points. The park is a permanent fog that has settled and shape-shifts at a frame rate so slow that we register the transformation only every few years. The surrounding area is endlessly in flux, its character tethered to the shifting real estate concerns that the park passes through. The High Line is a film that takes the city as it is, and after two plague years the park incarnates the post-apocalypse that it once only referenced – the empty office buildings, the deserted streets, the apartments rented then abandoned, blinking like rescue signals in the night.

Once, I heard that Gio Ponti designed a building by taking a leisurely walk around the site. At certain moments, he asked his assistants to hold up a wooden frame to the horizon. Wherever he liked the view, he later placed a window. In a certain sense, the house became a film of his walk that day. I never checked the veracity of this story, because I need stories like this in order to keep working.

For an altogether different lake house in Long Island, Diller and Scofidio imagined a 100-foot arc that curved toward the sea.

Slow House consists of a series of horizontal cuts that rotate ten degrees off axis every few steps – a walkthrough in time lapse, in which the view of the sea is endlessly deferred. Its form evokes the rotation of the wrist while drawing, as if the entire house was generated by a single gesture, from front door to rear window. At the far end of the house, a live video camera directed at the horizon feeds the view into a monitor placed in front of the actual window. The view by day can be recorded and played at night, or vice versa. The occlusion of the actual window means that neither window nor screen provides unmediated views of the water.

If anything, we register the idea that the picture window was a screen to begin with and brings us no closer to the natural world than any other form of media

(never mind that our eyes themselves are always already screens). The interrupted view is a recurring theme in DS+R’s work, from Blur to the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, to the amphitheater that faces a window onto Tenth Avenue over the High Line – a reversal of the modernist window that discloses an unmediated view of the landscape to the monocled, cigar-smoking patrician looking outside. Slow House is a machine for waterfront surveillance.

I feel uncannily anticipated by Slow House in my naive pursuit of Jeanne Moreau down the corridors of the city. I see film and theater as generative of an impulse to draw, to make form, and architecture as a way of reading film that, in turn, gives way to architecture again.

Almost 75 years earlier, the Casa Malaparte anticipated Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mepris (1963). As a controlled rush toward a precipice, a rush frozen into form, the house was already a film.

Some weeks before he passed, Virgil and I shared a conversation about OMA’s S,M,L,XL (1995), published the year after Flesh: Architectural Probes. In a moment of vanity, we decided that the work of every architect, whether they acknowledged it or not, was anticipated by one of a small set of books, but that the book was rarely the one that they believed it to be. There is a difference between the work we actively reference and the ones that unconsciously determine how we practice. Virgil believed the work of OMA to have anticipated his; he believed in the idea of advertising as architecture’s endgame, in collage both as poetic method and mode of presentation, and in the notion of building as logo. I suppose he especially saw the connection in his use of language as building material and of figures of speech as depth charges that upend the semiotic codes of art, architecture, and fashion – spaces where the production of meaning is violently policed beneath all the surface rhetoric about creative freedom. Now, in hindsight, I see Virgil and so many of us in Flesh, working in the afterlife of the codes that DS+R rearranged. I see that perhaps Flesh, and not S,M,L,XL, was his actual forebear. It is only in the writing of this text itself that I am discovering it. Grief takes on strange forms.

In 1990, Fawwaz Traboulsi asked Etel Adnan to write an essay on feminism for an issue of his magazine, Zawaya. In response, Adnan took two years to write what became Of Cities and Women (1993), an epistolary novel of sorts, composed of letters she sent Traboulsi from different cities.

Adnan sent her first letter from a feminist book fair in Barcelona. She visited Gaudí's Park Guëll and ate dinner with friends late into the night. She admired the women on Las Ramblas and fixated on a flamenco dancer.

She also revised her views on Picasso. For a time, Picasso lived in the shadow of Mont Sainte-Victoire, the same mountain that Cézanne painted over and over again. There, Picasso painted a still life of his Spanish buffet and portraits of Jacqueline. He never painted the mountain, yet every painting made at its foot bears some indelible mark of it. Sometimes the only approach to a subject is to turn one’s back on it.

Adnan visited a Cézanne exhibition in Aix-en-Provence, near Mont Sainte-Victoire, and spent time with its curator, Marianne Bourges. On the island of Skopelos, she watched women parade in and out of a disco. Later, she attended a conference on Ibn Arabi’s mystical poetry in Murcia. She mused that divine love was always feminine, from Nizam, the female theologian Ibn Arabi met in Mecca, to Beatrice of Dante’s Commedia. She passed through Berlin and Amsterdam; she fell in love with the women of Rome – the unmistakable saunter of Rossellini’s women.

Adnan’s journey ended in bittersweet Beirut, on a balcony overlooking the Corniche. By that time, her letters to Fawwaz had transformed into love letters to the cities she passed through and the women who inhabited them. “Beirut was like a thousand islands,” a friend told her at a cafe. “What a lost paradise.” For Adnan the exile, all cities contained fragments of the Beirut of her youth.

Every building is a montage, and memories – like poetry, like architecture – express themselves in fragments. Adnan somehow reached her subject through those fragments, through an archipelago that she navigated from the sleep side. As have I.

Credits

- Text: MAHFUZ SULTAN

Related Content

OTHER SPACES, OTHER ROOMS

Architecture of Resistance: The Barricades of Kiev

CLAUDE PARENT: The Supermodernist

In Conversation: IRAK – KUNLE MARTINS AND BEN SOLOMON

ARCHITECTURE POST INTERNET: ANDREAS ANGELIDAKIS in Conversation with Carson Chan

PHYLUM-H: “Medicine, Metaphor, and Architecture”

Anime Architecture: How GHOST IN THE SHELL was Built

Why Don’t Umbrellas Grow in the Rain? 12 Proclamations by Architect CEDRIC PRICE