Why Don’t Umbrellas Grow in the Rain? 12 Proclamations by Architect CEDRIC PRICE

|THOM BETTRIDGE

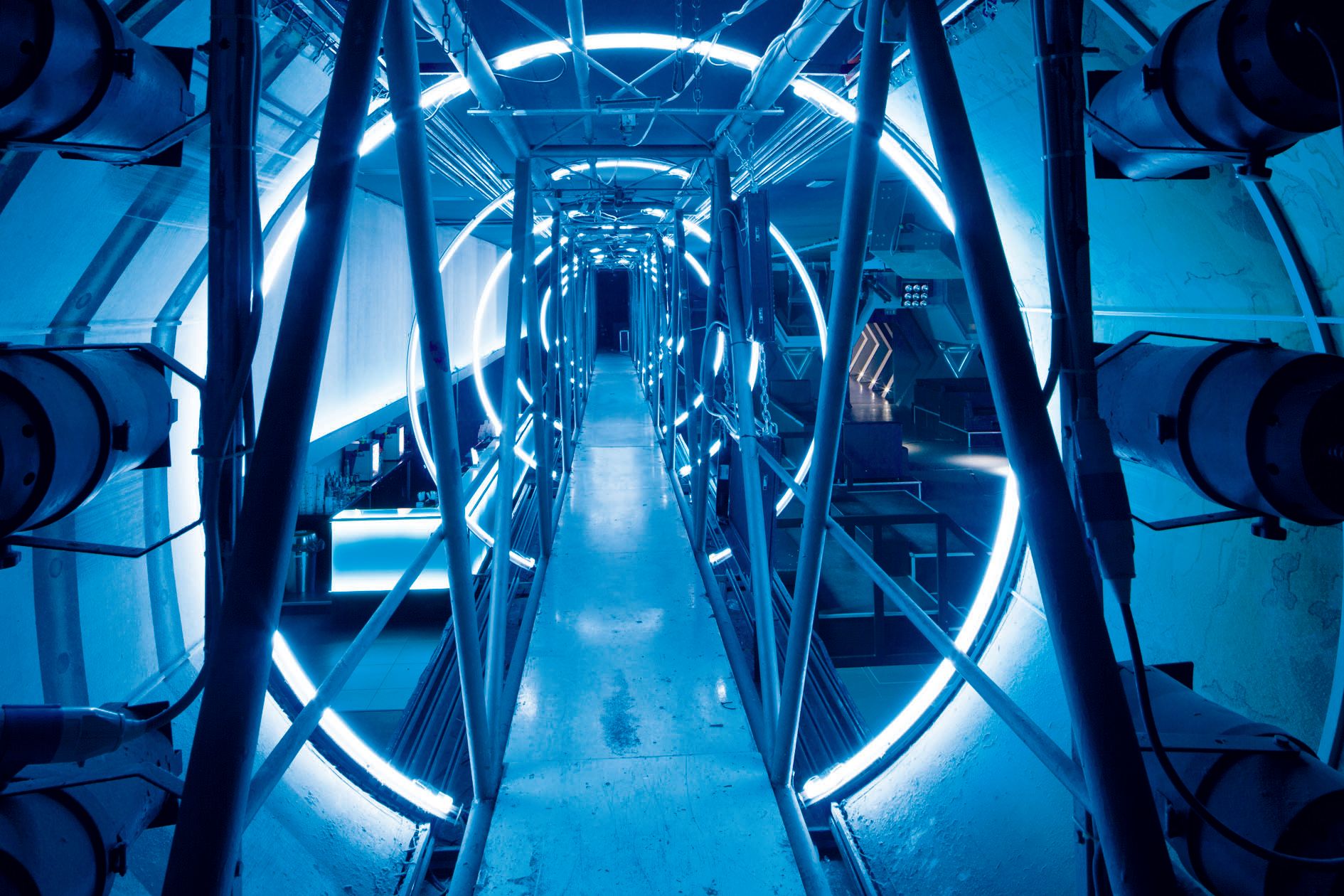

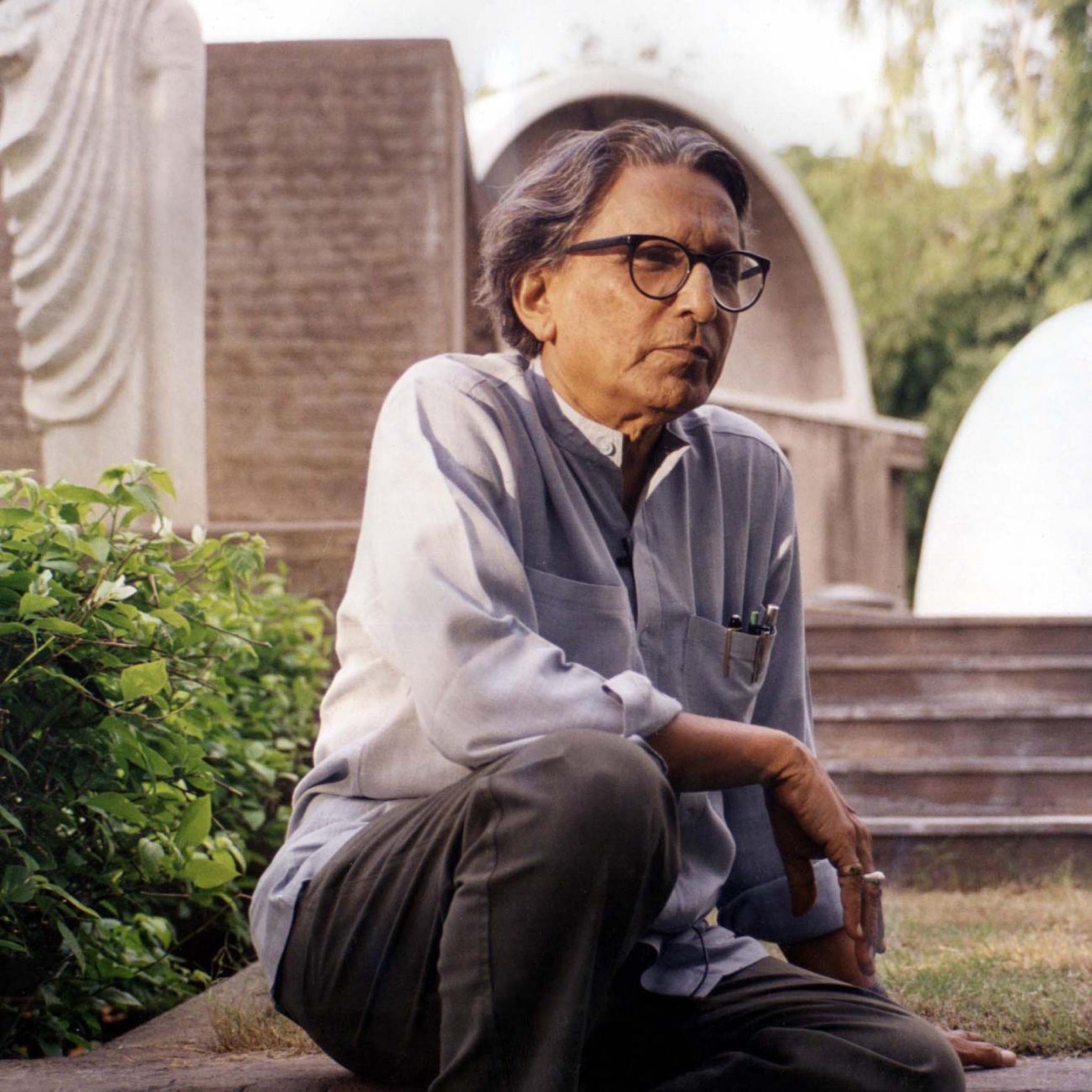

Cedric Price’s body of work is massive and slippery to pin down. Many of Price’s most radical projects – like the ultra-hybrid “Fun Palace,” which later became the model for the Centre Georges Pompidou – were never realized and live mostly in legend. In addition, many of his contributions to the field took place through criticism and public appearances, wherein he pioneered the role of architect-as-public-intellectual. For these reasons and more, the mammoth two-volume publication Cedric Price Works 1952– 2003: A Forward-Minded Retrospective, which contains his compiled writings and projects, reads like two stone tablets on radical design.

Price was a Socrates figure in twentieth century architecture, both in the sense that much of his work was not written down, but also in that he held an extreme skepticism toward his own profession. In a context where architects seemed to be blindly churning out buildings in the same mold, he went so far as to question the very idea of housing itself. This point of view goes beyond the “less is more” architecture cliché, undermining every assumption to the point of suggesting that the best designers should aim to delete themselves.

Below are 12 design maxims written by Price for a 1972 article in Pegasus.

ON SAFEFY PINS AND OTHER GOOD DESIGNS

1. Design is concerned with the conscious distortion of time, distance, and size. If it achieves none of these distortions, it is unlikely to be more than the elaboration of the “status quo.”

2. The apparent but unreal inevitability of the design of the safety pin is my definition of “good” design. It is the recognition, in time, of the usefulness and delight of the object (or system) that really establishes a consensus of the quality of the design.

3. It does not matter who designed the safety pin – we should just be delighted that they did.

4. The value of permanence must be proven, not merely assumed.

5. Why don’t umbrellas disintegrate in sunshine – or at least grow in the rain?

6. The house is no longer acceptable as a pre-set ordering mechanism for family life. Housing is rapidly becoming a consumable commodity. This is a major motivational force in the individual’s and family’s use of the house.

7. While increasing the world’s food supply or developing automation can be seen to be beneficial, there is little evidence to support the view that new houses or new towns, as we now know them, would increase human happiness.

8. Central to the activital shortfall is the inability of architects and planners to concentrate with sufficient expertise on the environmental servicing of people.

9. “How little need be done?” should be the designer’s first question. Then perhaps we would no longer have to pay people to paint TURN LEFT underneath arrows on the roadway.

10. The second question might be, “For how long is this successful?” The acceptance of the redundancy of design by the designer is essential. At present it is left to the rest of the community to do this. However, until the designer becomes concerned with determining the rate of redundancy of his design – not merely the life of the product – we will continue to electrify the grandfather clock rather than hand out wristwatches.

11. Shortage of time is likely to become an increasingly large element in the conscious design process: not merely in achieving a particular means but even in deciding whether there is time to bother designing such a means.

12. No one should be interested in the design of bridges – they should be concerned with how to get to the other side.

Credits

- Text: THOM BETTRIDGE

- Images courtesy of: CEDRIC PRICE ESTATE & the CCA