CLAUDE PARENT: The Supermodernist

|NIKLAS MAAK

He is the last Parisian Supermodernist. He built floors as ramps and supermarkets that look like cliffs. He was celebrated for his domestic landscapes and hated for his nuclear power plants. It’s time to rediscover CLAUDE PARENT.

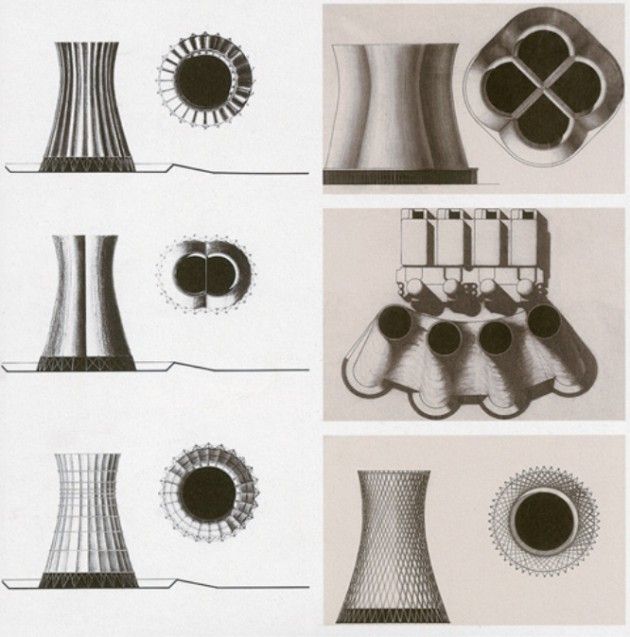

For every great theory there is a story, a myth of how the theory came about. In the case of French supermordernist architect Claude Parent, this story takes place on a beach in France, a dune landscape that engulfs the remains of the Atlantic Wall. From 1942 to 1944 the German army built around 8,200 bunkers over a 2,685 kilometer stretch of coast to impede an allied landing. Many of these bunkers slipped down the dunes after severe winter storms; toppled and askew, they’re stuck there, as if dropped into the sand from great heights.

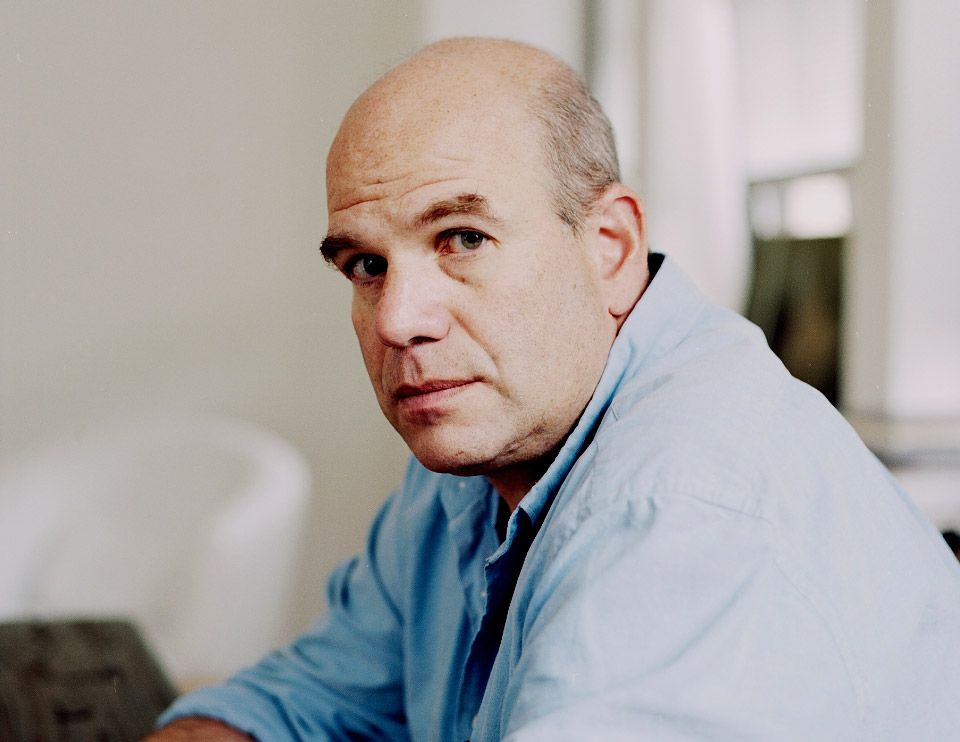

“Everything started with the idea of building things in an unbalanced way, with the idea of using a sloping floor”, says 87-year-old Claude Parent today as we meet him in his Neuilly office near the center of Paris. Then, the philosopher Paul Virilio “whom I was close friends with at that time, had seen a bunker which had sunk into the ground, and was therefore sloping, and had been very struck by it. He had experienced a feeling of vertigo.”

Parent, who drove a Jeep at that time, started to investigate these bunkers that were half-buried in the soft sand. “Inside, you tumbled through a strange room; the floor was so sloped that you couldn’t tell whether what you were standing on was a slanted floor or a former wall.” The concepts of “wall,” “floor,” “up” and “down” didn’t make any sense at all inside these ruins of a defense architecture. It was, Parent remembers, a sense of space that you couldn’t have anywhere else: a delirium, a dizziness that even the most turbulent Baroque churches couldn’t induce. At the time of that bunker visit, Parent was in his late thirties and already established as an architect. He had worked in Le Corbusier’s studio; together with fellow architect Ionel Schein he had brought American bungalow-style modernism to France in 1952 by building Maison G outside of Paris. He had designed a house for artist André Bloc out of artfully stacked boxes, as well as a few very American supermarkets and gas stations, and the “House of Iran” in the Cité Universitaire of Paris. He had invented a pneumatic racquet together with Yves Klein, and designed a car that looked like an oversized fly with wheels for legs. Claude Parent was one of the most successful architects of his generation but nevertheless rather unknown. Both things changed after he was haunted by the picture of a house with a sloping floor.

Since the visit to the bunker, the sensation of standing on an incline never let go of Parent. He began to deliberately bring things out of balance. He built a villa near Versailles for the industrialist Gaston Drusch that looked as if a Bauhaus cube, quite similar to the Atlantic bunker, had settled into the ground at a 45 degree angle – but stuff like that wasn’t extreme enough for him anymore.

That’s why he did something that made him a favorite of Parisian intellectuals while abruptly ending his until then commercially successful career: he decided to build only sloped floors.With Virilio he wrote pamphlets like “Vivre à l’Oblique” (living on the slope). And even today the 87-year-old speaks with undiminished enthusiasm about how this life on the slope could stimulate social relationships and steer them in new directions.

“Consider how boring it is within our homes. The kid stays in the assigned kid’s room while the grown-up sits on an inherited couch in another room. We’re completely overfurnished. What would it be like on the other hand, if space were understood more playfully, more free, if movement and being in a space also could mean climbing, reclining, sliding?” What would happen, Parent asked, if you make people group in ways different to those required by the given social parameters of “chair”, “table”, “sofa”, “bed”, etc? Can furnitureless architecture affect dynamics between people? Claude Parent explored this question – and in so doing became one of the most important social utopians in the modern history of architecture.

Commercially, Parent’s new living world was no success. Those who loved his “oblique” architecture the most – children – couldn’t afford it.

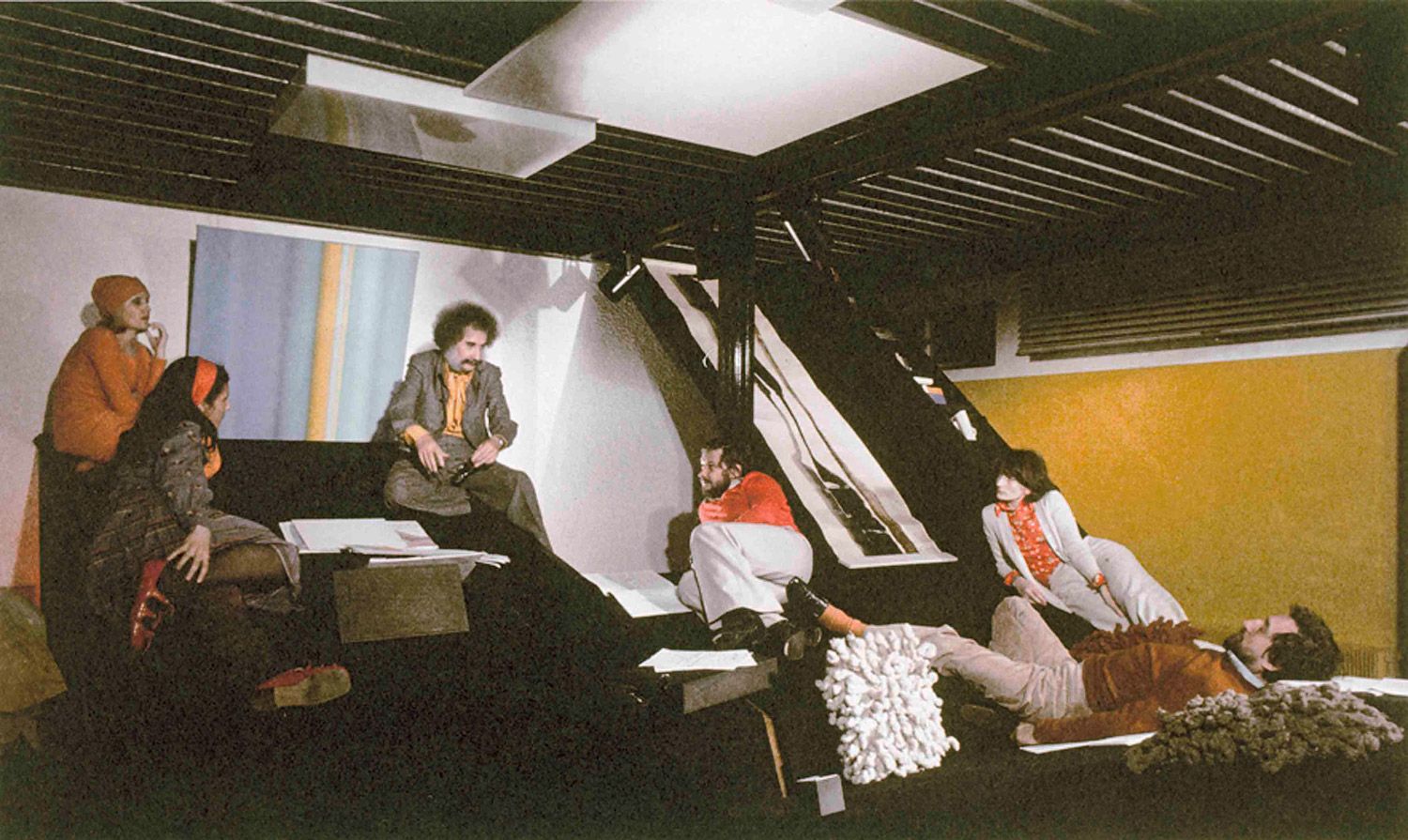

In 1970, he installed an artificial landscape made of slopes in the French pavilion at the Venice Biennale. He renovated his house. All furniture was eliminated and instead, ramps and sloped surfaces were built in. A photograph from that time shows Parent with family and guests: like a guru of unfurnished existence, he sits on one of these slopes while the others squat, lounge and recline around him as if they were the deconstructed return of the school of athens. it’s hard to tell what is a wall and what is a ceiling, to distinguish what is up from what is down. Through this dissolution of categories and order systems, Parent wanted to discover a new freedom. The house became a landscape again; you sat and rolled around like a herd of gorillas on the incline – a strong sociodynamic signifier in a time when sitting next to each other or lounging carelessly in public was still considered morally questionable.

Commercially, Parent’s new living world was no success. Those who loved his “oblique” architecture the most – children – couldn’t afford it. In the foreword to his recently published complete works, Parent’s daughter writes, “I ran with my dog over ramps and let marbles roll down – my parents had banned all furniture from the house, there were hardly any doors, you laid on plateaus and in caverns… After the day when the workmen came to install the ramps, the extraordinary became everyday life. It was exciting for me as a child. I didn’t belong to the bourgeois world any longer, in which you inherited valuable, classic furniture from your ancestors and ate at a table surrounded by six tall chairs… We ate lying down, at a small, flat table, which you could also lie under. At points there were soft spots embedded in the ramps that you couldn’t see – visitors would often scream in terror when they stepped on such a spot.”

Parent was celebrated as a hero of deconstruction, as one of the first to implement Derrida’s theory – to take an established system and not destroy it, but rather to take it apart and put it back together in a new, playful, less hierarchical way – in the field of construction.

DIZZINESS AS LIBERATION

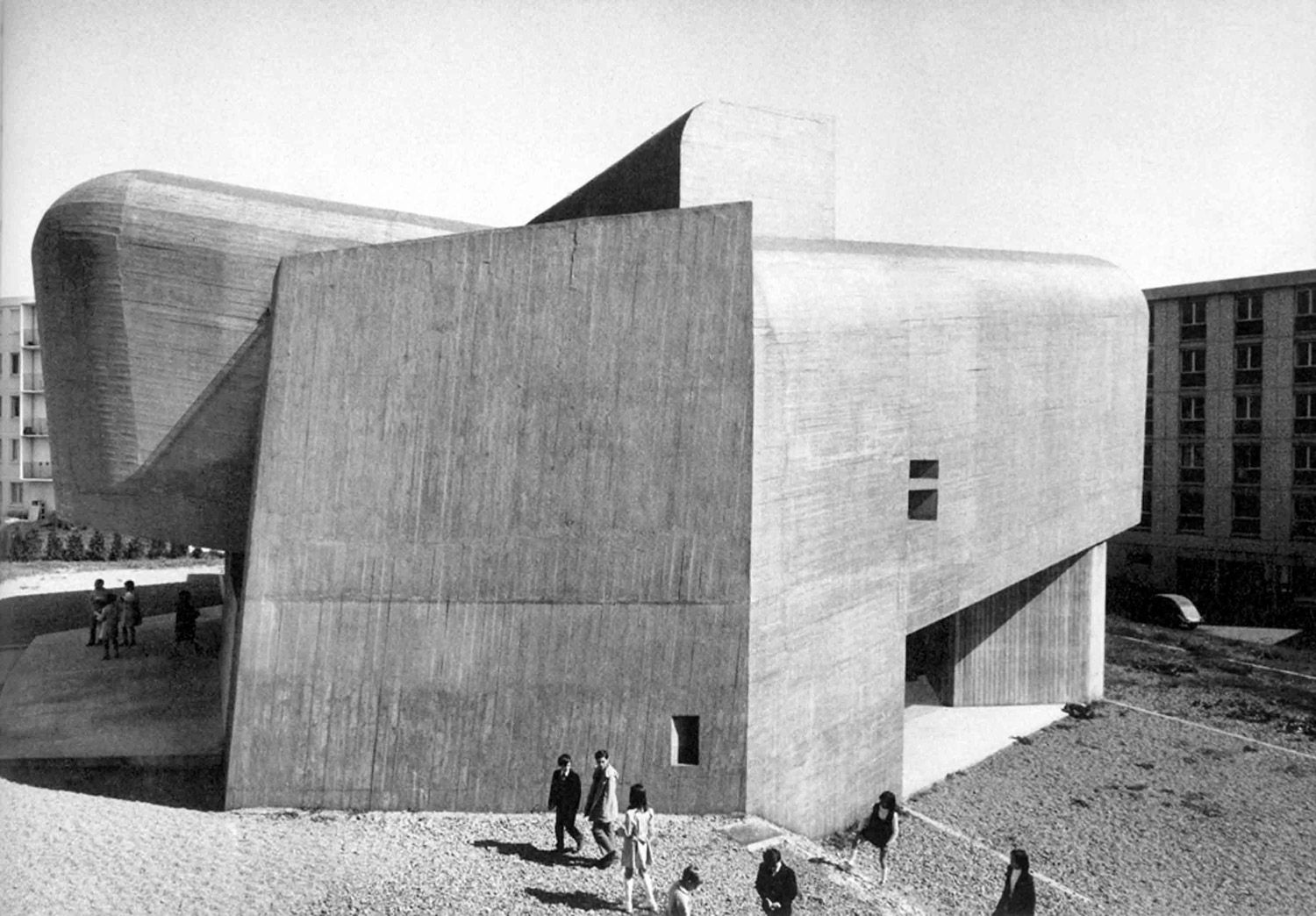

North side and apse, Church of Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay, Nevers, 1963–1966. The concrete, bunker-like monolith, with its spare sloping interior, was considered one of Parent’s most scandalous buildings. Photo: Gilles Ehrmann

“Nobody,” says Jean Nouvel, “could win an elegance contest against Parent.”

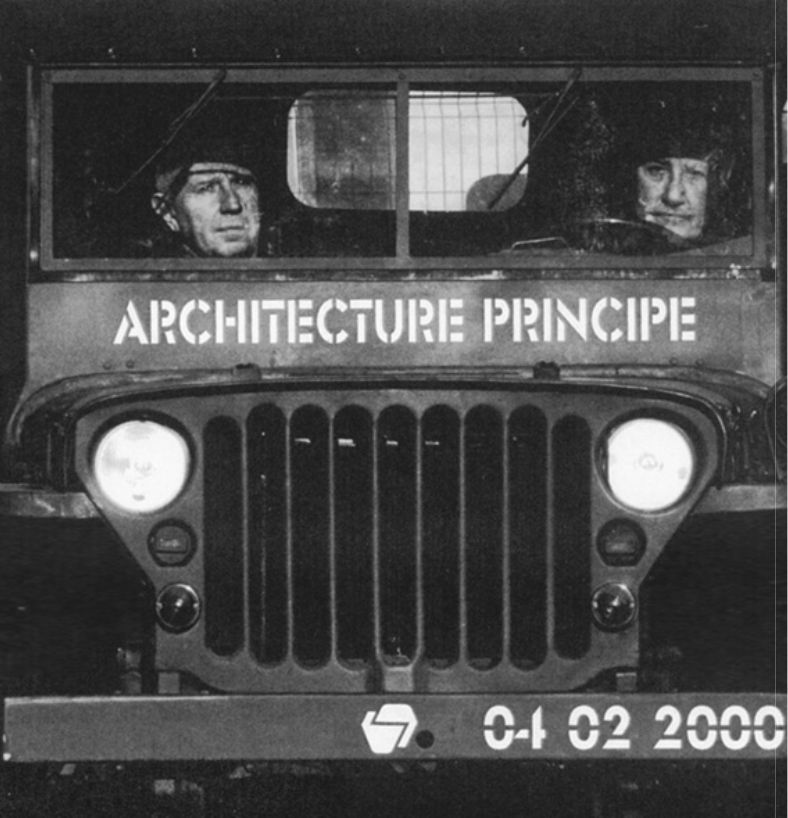

Parent believed in everything that was fast, so he also designed nuclear power plants. Jean Nouvel, Parent’s most famous student, describes how his teacher and Virilio drove through Paris in a khaki-colored jeep emblazoned with their “architecture principe” in white letters – two allies of a new architecture that wanted to liberate Europe from the boredom of rigidly geometric domestic designs.

Yet the first icon of the “oblique” was a church. It opened in 1966 in Nevers. From the outside, it looked like a bunker and the floors were as sloping and slanted as the concrete ruins on the atlantic. It was, you could say, a philosophical commentary on the fundamental crisis of living and domesticity. Bunkers, the most extreme form of protective shelter, had – as Virilio later wrote – proved to be militarily useless. They were nostalgic images, aesthetic promises of protection that, in the face of modern weaponry, couldn’t provide protection anymore.

What was the value of a house, if the walls could no longer offer protection in case of emergency? What did “dwelling” and “domesticity” mean after the experiences of war? These were questions, which after 1945 were discussed with the utmost seriousness by architects and philosophers like Martin Heidegger, in his essay “Bauen Wohnen Denken” (Build Live Think). Parent answered them with a euphoric philosophy of acceleration: if we’re already spinning, why not enjoy the tumble, put it to use, and celebrate it as liberation. The church that Parent built in the form of a bunker was the ruin of an old idea of dwelling; by adding slopes to this notion Parent converted the structure into a paradoxical thing between a cave and a hill, in which you couldn’t find any peace, but instead were exposed to an exciting feeling of dizziness.

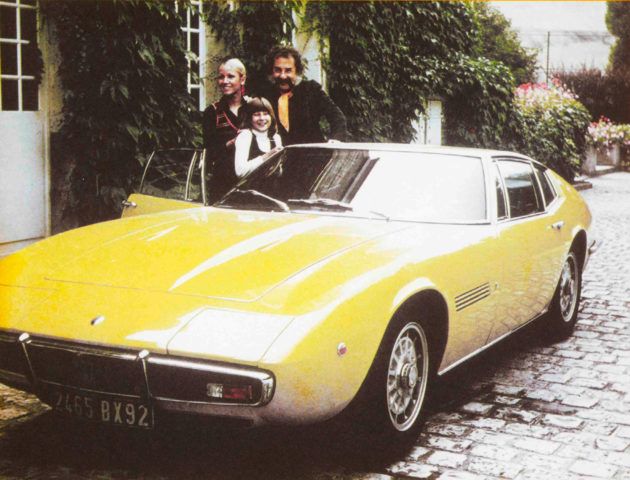

There are no level floors in the church of Nevers. Parent’s flamboyant appearances ensured that his theories got attention. Photographs show him in yellow bellbottoms, a black shirt and white leather shoes discussing things on his beloved ramps. Nobody, says Jean Nouvel, could “win an elegance contest against Parent. His suits, his ties, his dream car – like no one else he embodied his passion of aesthetics.”

HE REMAINS MONSIEUR FULL THROTTLE

Wherever Parent appeared as an activist of the new life, all signs pointed to turbulence, speed and a more dynamic condition; you couldn’t peg him as a strict critic of capitalism – he loved his Lamborghinis and Bentleys way too much for that. And even though he was the darling of leftist theory, thanks to his ideas of the “oblique” and their critical societal implications, in reality, as one of the last convinced Futurists he stood closer to the Gaullists and their progress-obsessed president Georges Pompidou, than he did to progress- and consumption-critical leftists. Parent embodies, like no other living artist, the full-throttle modernism which in France spawned the Centre Pompidou, the Concorde and scores of other grand and rapid machines, all of which Parent loved dearly (“You probably liked the highspeed train TGV?” we asked. “Yes, quite magnificent!” – “and the futuristic Citroën DS?” “No, that one not so much, it was way too slow!”).

In light of this penchant for all that is grand, supersonic and global, it is not surprising that parent didn’t hesitate when he was asked to design the (up till that point) biggest supermarket for the chain Gouletturpin. “They were the first who wanted architecture for their shopping centers. Other chains believed that their halls should look extremely heap, so that people would think, that box looks really cheap, the products must also be really cheap there, I’ll go there.” Parent tried something else. He turned the Hypermarché into a megasculpture, a synthetic massif of concrete cliffs and tilting masses. Thus, the aesthetic of the sublime reemerged at the centers of pop and consumer culture.

Many who had celebrated the theory of the “oblique” as a liberating religion more than resented Parent for placing a great monument to shopping lust right in front of their consumption-averse noses. Parent was now a contradictory, frustratingly complicated case. The solution to his apparent contradictions between societal critique and system affirmation could be found in Parent’s passionate Futurism. He was and remains Monsieur Full Throttle. In order to further his Futurist expansionism, supermarkets were as good as living on launch ramps, and as good as the project which ultimately ruined his reputation among architects and social critics: the nuclear power plants he built in France.

Can furnitureless architecture affect dynamics between people? Claude Parent explored this question – and in so doing became one of the most important social utopians in the modern history of architecture.

“At that time people were rather critical of nuclear energy. You had earned enough money from your supermarkets. Why in the world did you, right after that, accept a contract to design several nuclear power plants?”

“I’ll tell you gladly. At that time there wasn’t anything for me that was faster and more powerful than the atom. It was a huge feat to bring this energy into form, to tame it. I found everything having to do with atoms and particle acceleration good. It was great and modern. Back then you thought about atomic waste as little as you would think about car exhaust. It was that simple.”

It should be added that Parent recounts all this in the gentlest, most endearing manner. As a person, he is so disarmingly nice and quietly intelligent, it’s hard to believe how high he could get on the technical wonders of the twentieth century. Parent would not be forgiven for choosing to erect not only giant consumption bunkers but also the nuclear power plants at Cattenom and Chooz. He was criticized harshly and largely forgotten by the international discourse. Between 1990 and 2000 he got by working on smaller projects, building shrill, strained, deconstructivist schools and learning centers, but his name hardly ever surfaced anymore.

Another view of the bunker church in Banlay. Photo: Gilles Ehrmann

Only now a new generation of architects is discovering his theory of the “oblique”. A retrospective in Paris was recently devoted to him, and the new social landscapes being built by architects like Sou Fujimoto with his climbing-wall style houses, or SANAA with their undulating university campus in Lausanne [see 032c #19], aren’t imaginable without Parent’s theory of the oblique. The more intensely the question of how spaces and houses could look in the future is debated, the more recognized the significance of Parent’s spatial philosophy will become. It’s only in France that Parent still faces resistance. When people wanted to buy the architect’s house in Neuilly, they insisted on removing all the ramps. A villa with sloping floors, Parent learned, was completely unmarketable there.

TWELVE SUBVERSIVE ACTS TO DODGE THE SYSTEM

1. OPEN THE IMAGINARY

2. OPERATE IN ILLUSION

3. DISLODGE THE IMMOBILE

4. THINK CONTINUITY

5. SURF ON THE SURFACE

6. LIVE IN OBLIQUENESS

7. DESTABILIZE

8. USE THE FALL

9. FRACTURE

10. PRACTICE INVERSION

11. ORCHESTRATE CONFLICT

12. LIMIT WITHOUT CLOSING

Claude Parent, 2001

Credits

- Text: NIKLAS MAAK