In Conversation: IRAK – KUNLE MARTINS AND BEN SOLOMON

|KATJA HORVAT

After so many years, and so many stories told and written, the idea of what IRAK really was drifts more and more toward a fantasy of what each of us wants it to be, or thinks it was. Irak repeated the patterns of the past whilst creating a new aesthetic vision that served as a new culture of that time. If you think of the NYC downtown scene in the late 90s and throughout the 00s, you think of Irak. Through their interdisciplinary practices, members of the graffiti crew a priori became one of the most influential collectives of the art world, and continue to shape art, fashion, and culture to this day.

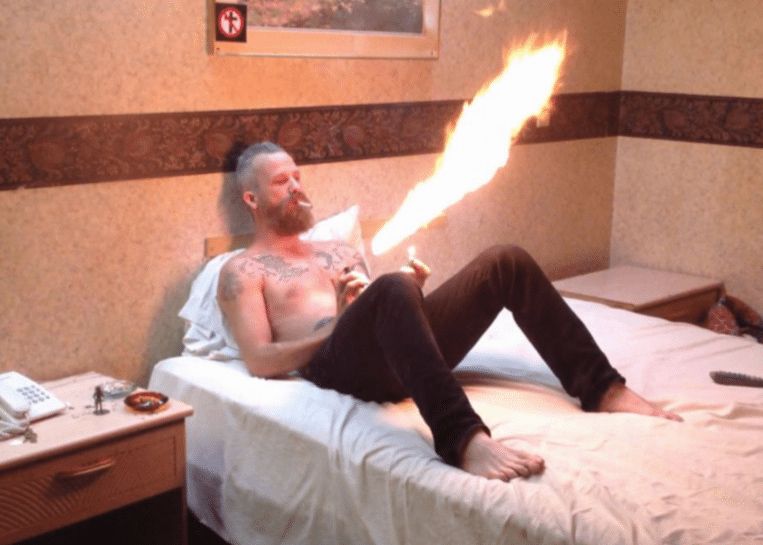

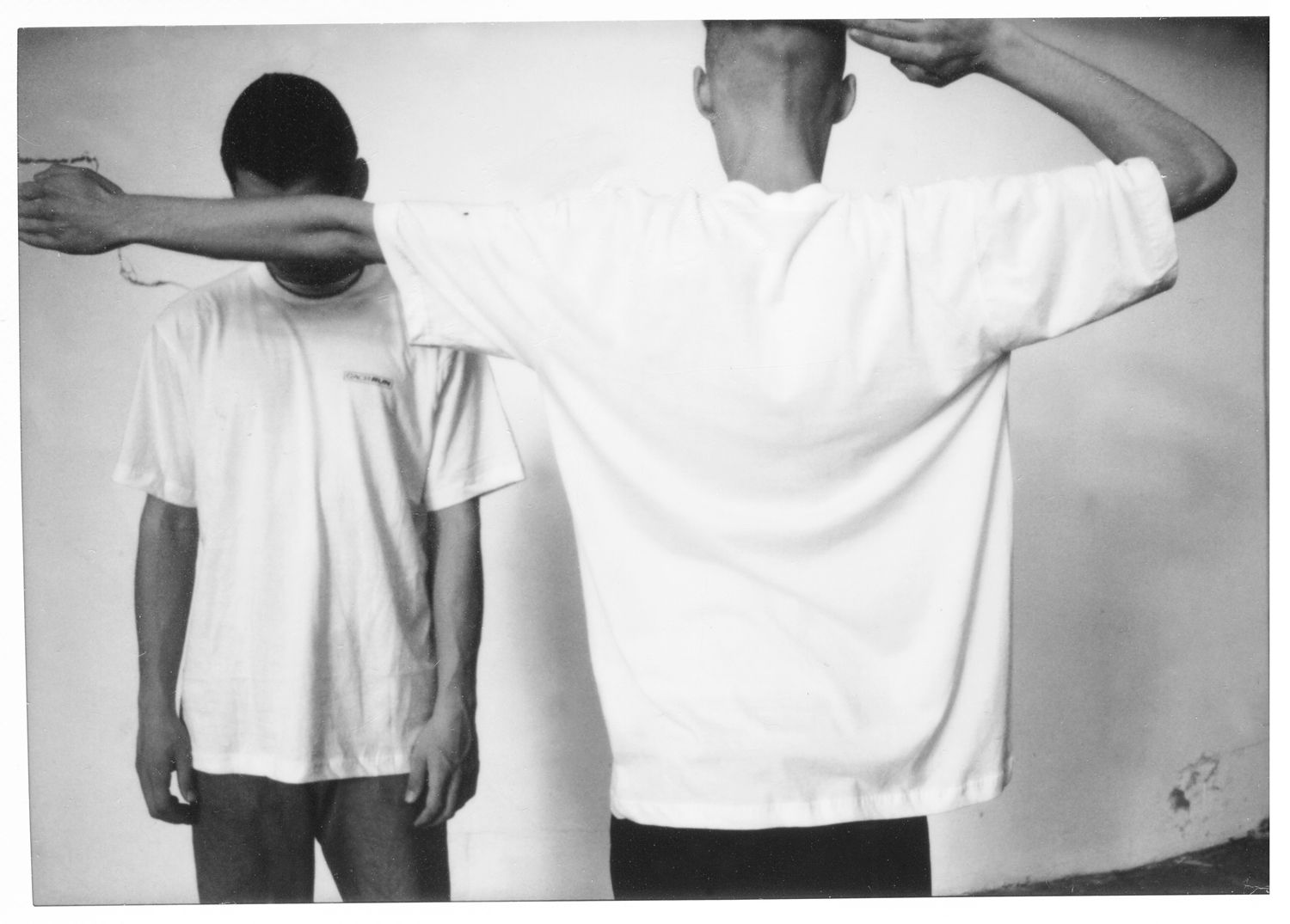

Founded by Kunle Martins, members of Irak include Dash Snow, Dan Colen, Ryan McGinley, Ben Solomon, Jason Dill, Aaron Bondaroff, and Mike Cruz, among others. The collective was a perfect concoction of reckless behaviour mixed with talent, community understanding, and how to interact with the city to make the playground it is most beneficial to you. The birth of new media influences and brands around them, and NYC itself gave Irak more tools to create and later distribute their vision and ideas on a broader scale. They documented every aspect of their lives, and changed the entire trajectory of how their careers unfolded. Those images gave entry into a world many lacked access to but wanted to partake in the culture of. Irak gave a fresh creative energy and visual communication that transformed the context of the space and human experience and furthered a sense of community.

“Forget if the tag was good, if the graphic was dope, it's the spirit, right!? It's the energy. Is there something about you that makes you authentic? That is the most important thing in our culture, and people forget that a lot. They say you have to be confident to do something. Sometimes you can just be an introvert and a weirdo and it comes out as confident because it is your own. But can you walk in a room and people automatically feel your energy? I think that is a true art form of culture. Can the air be so thick because the attitude is so strong? And I think that's what it is all about and why it survived.” says Aaron Bondaroff.

Today, Irak embodies the spirit of a certain place in time. It was born out of an unintentional urge, despite coming from intentional actions. From the very beginning, their cultural influence transcended limitations and even reached me, a kid from Slovenia. Seeing how hard they were going, their forms of language, and their interactions between themselves and the city around them, helped me enter a new relationship with my own ideas. Ideas on what I wanted out of my career, my life, and my future. From the first moment, I was hooked. The power of their influence and the path I decided to take brought me into their world, literally. Today some of these people are my collaborators, but more importantly, they are also my friends.

I sat down with two of them, BEN SOLOMON and KUNLE MARTINS, to kick off this new series of conversations in collaboration with 032c.

Katja Horvat: Let's start at the beginning — how did you two meet?

Ben Solomon: I don't remember how we first met, but it was probably in Washington Square Park, a passing kind of vibe. Or on the 6 train, when you had shells in your hair? I didn't realize for a while we were actually friends.

Kunle Martins: Oh for sure, we were beefing at first. I would make Jewish jokes and then Ben would make gay jokes, and then we hated each other.

BS: Hated each other? [Laughs] You used to be an angry kid.

KM: I was angry and horny. It was just an argument about dissing each other's tags. It was adolescence boy, testosterone stuff — graffiti writers, masculinity, toxic, etc.

BS: I am sure I was also fairly annoying in my own way.

KM: I mean, you were just this hip-hop, Jew, know-it-all guy. You kept saying, “How do you not know that?” I was like, “Yo, I don't know anything!”

KH: How old were you guys when this all started?

BS: Kids! They were all around fifteen, sixteen, and I was the youngest, two, three years their junior.

KM: It's never a good move to be the youngest in the crew while you also want to be the know-it-all. Ben knew so much about music, movies, and art though — all of which I had no clue about at the time. Because of that, I also felt the urge to be around him, or others that knew a lot, to just learn. It was refreshing to be around people that were my age and were up on cultural stuff.

KH: It's rare that so many people from the same crew made it, building solid careers for themselves.

BS: Yeah, people that somehow managed to have a career or die.

KM: Or die, yes.

BS: We are also lucky. Uncoincidentally, we as a crew, went through so much good and bad. We lost so many people, so much shit happened. For us that are still here, we learned lessons the hard way. We always had the mentality of a group — it was never just one guy that did it, it was many pieces of a puzzle and each had something going on that benefited the other.

KM: It was a magical time. I don't really know how to explain it. It was like magic in a bottle. You can't recreate that but ironically it does recreate itself. With every generation there is a crew coming out of it, some more impactful than others, but it's a loop. We were also lucky to be in NYC, and not Nebraska or Oklahoma. Nowadays you can probably make it there too, but at the time when we were growing up, the fact we were in NYC was a big part of it.

KH: By the time Irak was formed, graffiti in NYC already had so many lives, deaths and forms. These were the result of the ever-changing landscape of the city and were catering to the times you were in.

KM: We had the privilege to learn from other crews before us and follow in their footsteps. We owe our success to people that were mentors to us. There were already tons of graffiti crews when we were starting, so we had a template and knew what worked and what did not. Some even took us in and made us part of their world. To a kid, this is godsent, to be validated by people older than you who you look up to.

BS: What we were doing had been happening in New York since forever. People we were looking up to essentially invented graffiti, hip-hop, streetwear — that was the blueprint. At the time, diverse groups combining high art with street art was unimaginable. But the city is constantly changing and growing up and growing old. In New York, by default, your thing is going to be “Oh it used to be this...” and people older than you are like “Welcome to the rest of your 'it used to be’ life.”

KM: Skuf YKK said in an interview “New York is so cosmetic.” It just made so much sense, now I fully embrace it. First, great use of the word cosmetic. If Skuf from Bushwick is saying NYC is cosmetic, and he accepts the fact that it looks a certain way today and it will look a different way tomorrow, and that shit is okay, then I am ok. It almost needs to be that way. People who hardcore lean into what NYC used to be have the mentality that if they are from this city, the city owes them something. That continuity and familiar feeling — all your old places should be there, kids you went to high school should be there. But NYC is not that. Everybody leaves, it's just one of those cities. It’s weird, I could never be anywhere else but here. It calls you back. You need it, but it's also so toxic. The city will never love you back the way you love it. And, everyone here is crazy, especially people that are from here.

KH: How many of your tags are still around the city? Can you even keep track?

BS: Graffiti is temporary, just by nature itself, it's a fleeting thing. The city has undergone an insane amount of physical cosmetic changes, especially Lower Manhattan. Buildings with some of our best pieces are not even standing any more. But there are little preserved spots that no one knows about. I still have a tag from 1998 behind the bodega on 6th Avenue, across the street from the basketball court, that no one even knows exists.

KM: Unless you’re VFR.

BS: Right! When the building goes, that's one thing, but when a kid on six Xanax bars who just started writing a few months ago goes over the last living thing from that era, those things hurt.

KM: It's going to happen, and it's been happening. You can wage war on everybody and try to tell them how much history there is, but that's New York. I probably did that to somebody back in the day. I remember not caring. I just took spots, and people are going to do that with me now.

KH: Before you landed on your tags, how many trial runs and different names were there?

KM: Oh boy, before I settled on Earsnot?

BS: The super logical Earsnot. [Laughs]

KM: The super amazing one, yes. Probably around ten before I ended with Earsnot. I gave up trying to have a perfect tag, and that one somehow ended up sticking around and it looked good visually. I didn't give a fuck what it was. I was trolling graffiti writers and thought “Let me just write this thing and it will be funny” and then whatever. But people started to notice it, and I was like “This shit? This is what you all notice after trying out with all these perfect sounding razzmatazz names?” They picked up on something I wasn’t even writing in any kind of graffiti hand style!

BS: Graffiti is this weird Catch-22 because name is all you got. But hypothetically name is something that finds you, you don't find it.

KM: Did you always write KS?

BS: No, I had a bunch of horrible names before that. You just try and find the right one. I mean there were KS’s before me and there will be KS’s after me, it's all over. But sometimes you go the Kunle-route and you pick something no one else is ever going to pick and it's the most unique name which sort of changes the trajectory of it all. And sometimes, for all intents and purposes, your name is generic like mine, but you can't write it like I do! Your KS is not my KS — you inject value into it. And that's the cool thing about graffiti: it's like a worthless exercise that you do, but once you do it, it's worth everything. With graffiti, you are just giving it to the world, and a lot of the times what you get back is actually negative.

KM: Graffiti is the ultimate — this is what I got, and I give it to you, for free!

BS: If you want it or not. [Laughs]

KM: Unsolicited for sure, and I want it to be everywhere. This is my marketing. This is my advertisement of the self that I want to be. Plus, once it's out there, I don't really care how it's perceived. Once I share it with the world, my job is done and what everyone thinks of it is none of my business.

KH: Where do you stand when it comes to showing graffiti in museums or galleries? The conversation around it is polarizing. Some say it should be recognized as any other art form, therefore there is a place for it in a contemporary setting. Others claim it loses its value and context if you remove it from its original intent or setting.

BS: For years and years people have been trying successfully —and often unsuccessfully — to put graffiti into the galleries, museums, collections. But it comes and goes. You just want to be creating one way or another, and to be part of the conversation if it involves your culture, your work. You don’t always have to be the center of that conversation, but you are going to contribute to it either way.

KM: When I was younger, I hated that graffiti was considered art. I can do fine art! I can paint! But I write graffiti to be bad. I write it to commit crime. And I hated the idea of people walking into these white, pristine rooms with white wine and there are tags. It was just weird. But then as you get older you realize it doesn't have to be any particular way. There are multiple identities to this and museums need it, they need to show it. All these works tell a story that many people would never see or hear if it's not put into a certain frame and presented to them in a way they can understand. And it's nice to be part of the conversation as an ageing graffiti writer — we are all going to be dead.

BS: Wait what? We are all going to die? [Laughs]

KH: What are you talking about Kunle? We are not here forever?

KM: Sorry to break it to you guys, but we are all going! What I am saying is, we don’t get much time here, and I want to do as much as I can while I am still here. It's insane to think I made a living out of something I wanted to do as a teenager, not many writers get that chance. I am happy to be part of the conversation, and it is great that after all these years we are still friends, and we are here talking to you about this.

BS: Alluding to what Kunle is saying — there were also so many writers we looked up to who went out the hard way. They didn't have any success even though they were the very best, and they literally gave their lives to it. With us, it's a mix of it all, a little bit of luck, timing. It's not like we were the best or we invented anything here. There are people who literally brought this to life out of thin air, and they didn't get to be put in to a museum. No one knows their story, their names. The legacy of graffiti is this massive thing. At the end of the day you need to acknowledge those people but also recognize that somehow, some of us were put in a position where museums, galleries, and brands just prefer to engage with us more. It's great to be put in a position to tell a story and to be heard, but then when you are in museums or galleries or whatever you do, you just try to have a conversation around it that's broader than you, as this whole thing is way larger than just us.

KH: The appeal of something is super subjective. I feel that with Irak, and why even I got so hooked up on it, is the lifestyle itself. It was not necessarily about the graffiti — it was about everything else that happened around it. The lives you guys were leading, and how hard you were going.

BS: Yes, I think lot of people that were into what we were doing saw this as sex, drugs, and rock & roll. We were also so diverse we could cater to any taste really, and that's cool. We used it to our advantage.

KM: Also, the deaths. For us it was really real. We felt it every bit but for people outside of our crew reading and tapping into what was happening and how, stories as such were sensational, it added to the myth.

KH: I think what's also crucial here is the documentation of everything. If we look at all the Polaroids from Dash or images that Ryan took. All of a sudden, through all these photographs or videos, things became real. It was not just a story anymore that could or could not be real, now it was all there for everyone to see.

BS: Yes! I am glad you said that, because that is a better point and has more truth to it. The fact that our thing was happening at the birth of this modern media, and we were documenting it and having all these images and videos, changed the whole landscape of graffiti, the culture around it, and us as a crew. Before, there were magazines covering graffiti, but everyone's reference point was subway art and style wars. It's not like we were the only people, but in our era, we were so diverse as a crew. We had Ryan who doesn't even write at all but he takes all these images of us, brings a whole new layer to this thing. It's like you said, not just something you heard, now there were all these things actually showing you exactly how it was, what we were doing and how we were doing it.

KM: It was both — first Ryan or Dash or whoever it was wanted to take our picture, but we were also down to be photographed, and take our shirt off and just do all the stupid shit. It was very reciprocal how the whole thing operated and what we were all getting out of this. Every single element was needed for us to be here right now and still talk about this all these years later!

Credits

- Interview: KATJA HORVAT

- Images: IRAK

Related Content

JASON DILL Takes us to Hell and Back to FUCKING AWESOME

VASYA RUN: A Russian Graffiti Performance Turns into a Program for Spiritual Emancipation

“There Is a System of Aesthetics That Only Graffiti Writers Understand”: Martha Cooper Runs with 1UP in Berlin

Special Commission for 032c by DAVID OSTROWSKI

METALLICA

CAN IT SKATE?: Skateboarding’s History of Cannibalizing the Footwear Market

To Know Russia, You Must Skate It

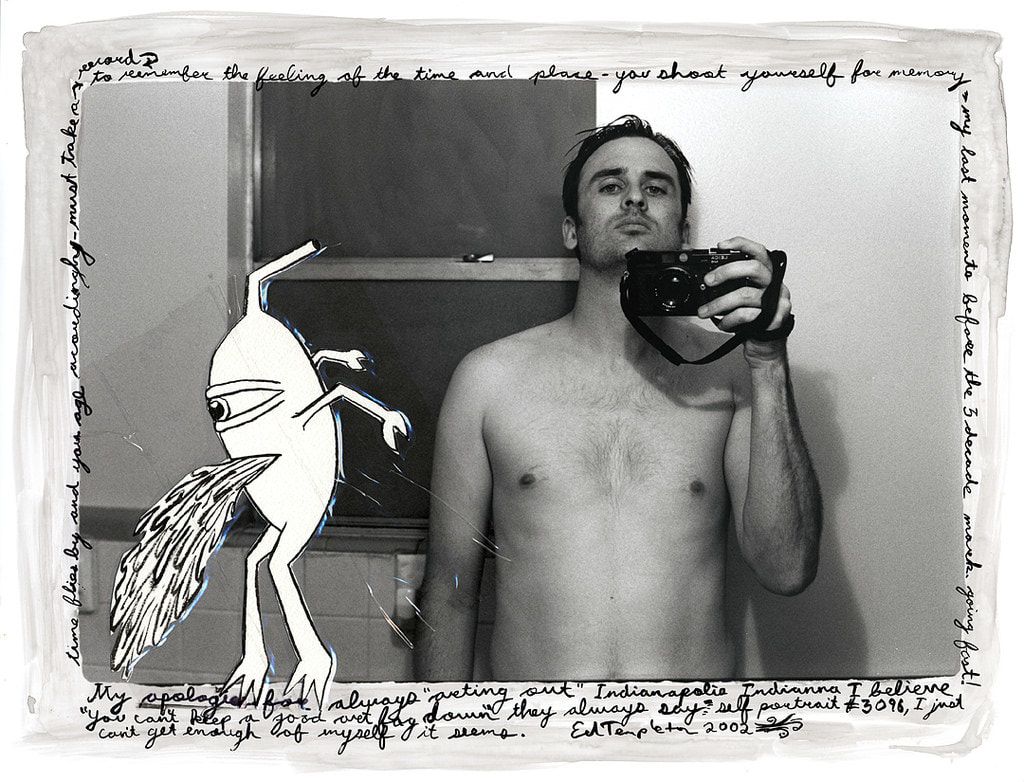

Welcome to Hell: Skater ED TEMPLETON Exhibits Suburbia