Fake Press for a Fake Band: Reece Cox

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

“I long felt some vague but strong conviction that sound is much greater than what music permits and that the arts have generally been rather lazy in providing space for its potential.”

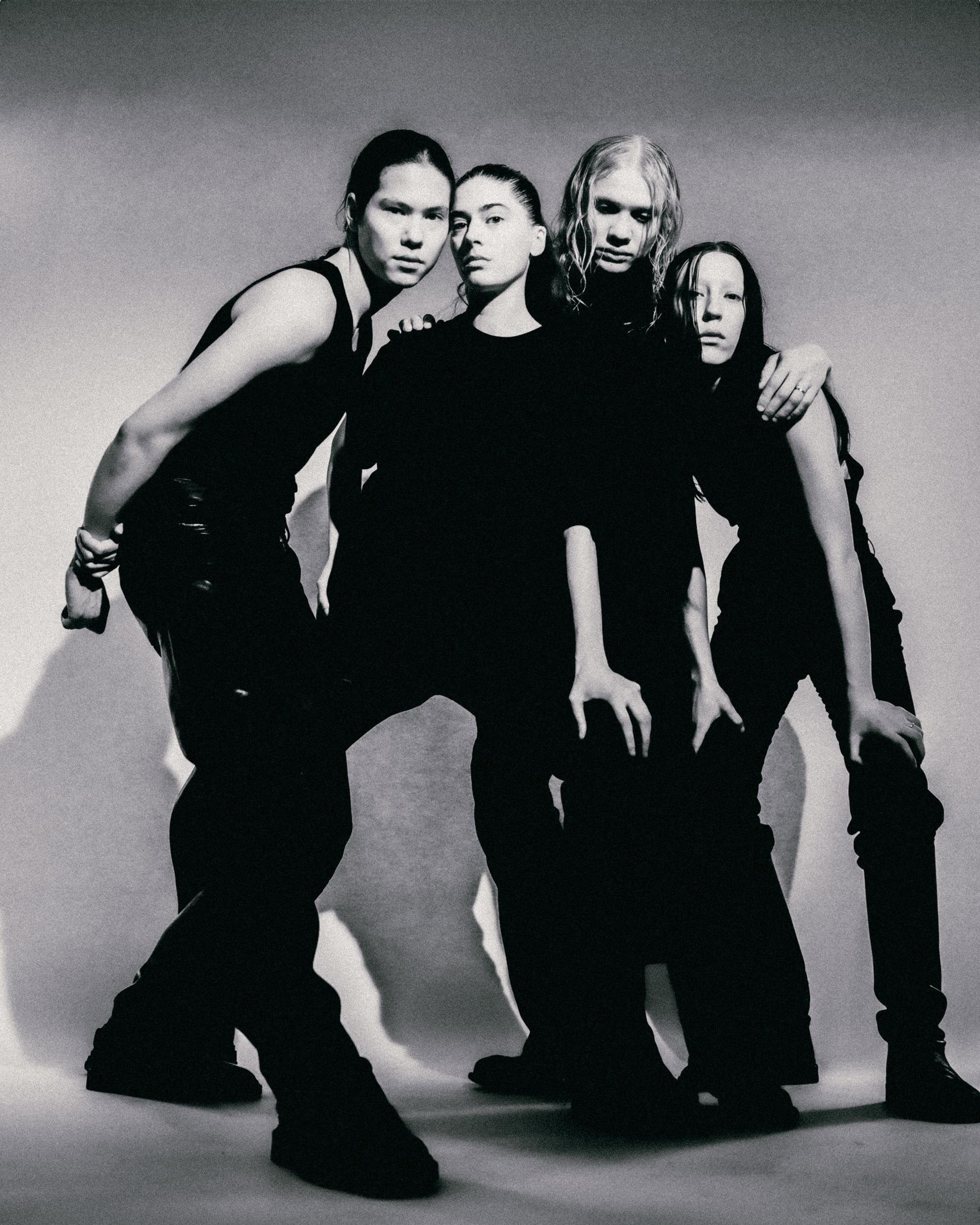

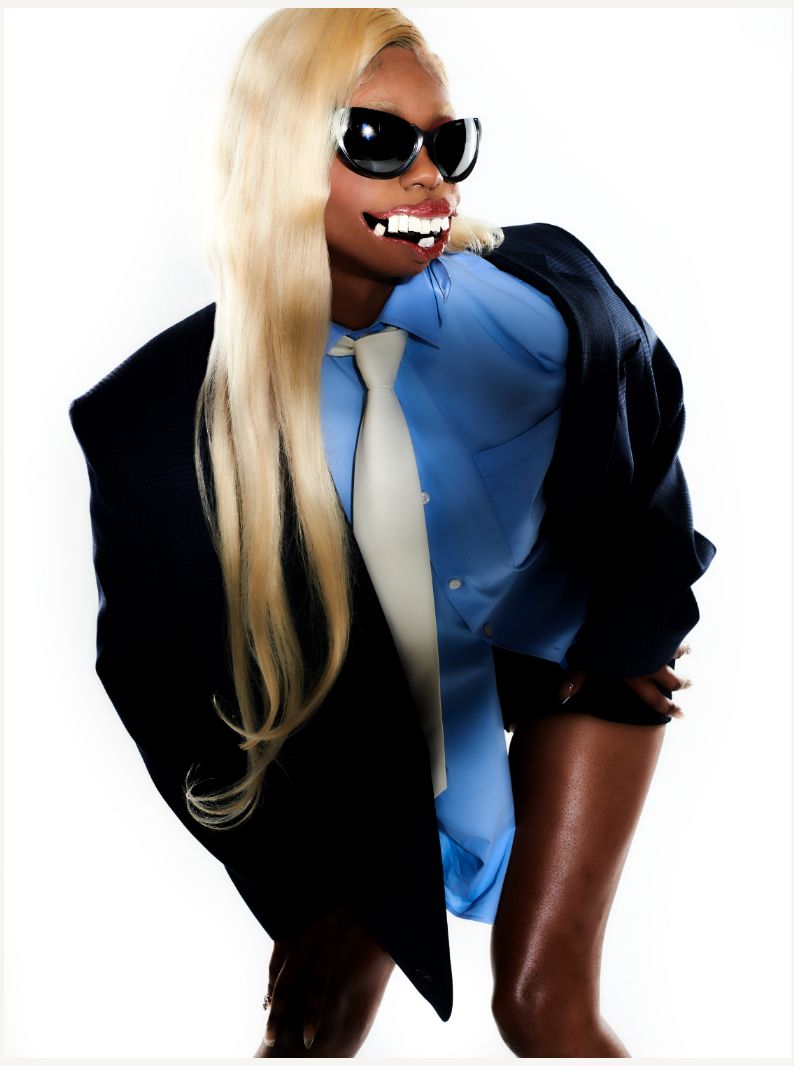

Reece Cox, Poser Faux Press (for Zweikommasieben), 2024. Photographed by Kasia Zachrko. Courtesy the artist

Artist Reece Cox’s project Poser consists of a band that is entirely fictional but that nevertheless performs in front of audiences and gives interviews to magazines—under the one condition that Cox writes both the questions and answers. Poser utilizes the concept of a music group as a case study to question the “industrial” production of music and art, where it seems as if image-making is superior to actual content.

Cox and Claire Koron Elat are here in conversation about a fictional band that performs irl, the professionalization of creativity, and the disconnect between creator and product.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: I want to start with your project Poser that you presented at KW, Berlin last summer and again at the Volksbühne Roter Salon in December. It’s a fictional band that focuses on the superficial performance aspect rather than the actual content of the performance. How did you come to develop this project?

REECE COX: Poser is a culmination of ideas and questions I had been fixated on for a while. I suppose I still am but they change all the time. It’s hard to say it neatly but I was essentially interested in how a certain kind of music works, not just the sound, but how music is produced, perceived, consumed, etc. I wanted to look at how a popular band is a sort of post-war industrial product born of PR agencies, booking agents, stylists, producers, ghost writers, increasingly cheaper instruments, tech, and distribution technologies—and ultimately also photography. Most importantly, I was trying to understand the significance of images in making something like a music group or a band legible as something cohesive that tries to obscure the industries which produce it. I first wanted to approach these questions by making a band that doesn’t play music, just to see if it’s possible. By now, I’ve proven that, so I feel way more free to take the idea in whatever direction I want. I can ask more nuanced questions through the project or try to break it and turn it into something else. Basically, Poser is a band that has no members; a group that’s just an idea but can be recognized as something cohesive, predominantly through images.

At KW, I produced what was functionally a play disguised as a concert where musicians and actors play the role of a band but very little live music happens—mostly playback and acting. I was especially obsessed with Dan Graham’s theater works at the time, and KW let me stage the piece inside Café Bravo, a glass pavilion and functional café Graham designed in the 90s which sits in the middle of the KW courtyard. So, the audience was outside looking in through the glass at these non-playing musicians standing on elevated stages with the sound projected outside.

Roter Salon, though, was something else. The event was a magazine launch for issue 29 of zweikommasieben wherein the magazine had allowed me to produce a sort of faux feature about Poser, where I wrote the questions and answers of an interview as if I were a journalist speaking to this anonymous group of artists who claim to be Poser. In the interview, they’re kind of evasive and give me a hard time, so it’s entertaining to read but is secretly a manifesto in disguise—or at least a record of my thinking up until that point.

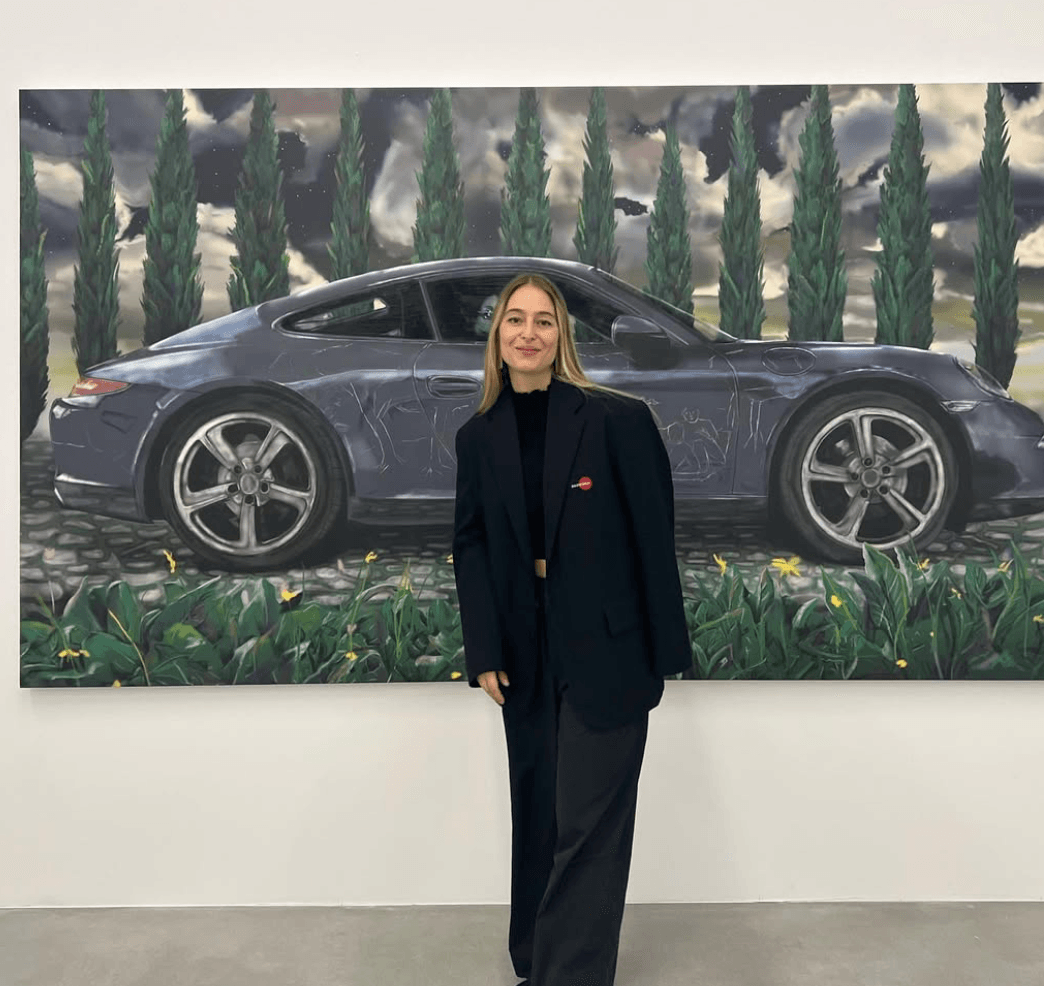

Reece Cox, Destiny Pain 06 (left), Destiny Pain 00 (center), and Destiny Pain 07 (right), 2023. Silkscreens on 300g paper, 100 x 70 cm (39 x 27 inches). Courtesy the artist

When [zweikommasieben’s] Mathis Neuhaus invited me to bring Poser to Roter Salon, it was the first time I had been asked to do something with it in an actual music venue. The previous three were in galleries and a museum, so, naturally, I felt I had to avoid using the stage or else Poser might end up coming off as a normal band—and probably not a very good one. To get around this problem, I produced a scenario where the band members were all sitting backstage as if biding their time, waiting for a gig to begin, and ultimately not under any pressure to perform. I worked with a video team to compose this scenario as a sort of on-screen musical that is almost like a sequence of still lifes and video portraits, but where very little action happens, though there is some live music. This backstage scenario was filmed and projected live for the audience inside Roter Salon, where there were suggestions that it was happening in real time but was deliberately misled as to what was live or a prerecorded video or audio—that is about what was real versus staged, and so on.

Whatever I’m doing with Poser, it always starts with the question of what kind of images it might produce; everything else works in service to, or is a byproduct of, making images. Ironically, Poser was supposed to be my “I’m quitting music” project, but as it turns out, I just needed to find a new way of working. My background is in painting, and while I’ve maintained that practice mostly in private over the years, at some point, music took over. I was always uncomfortable with being a musician, especially whenever I started to professionalize in some sense.

CKE: Do you think that if creativity gets too professionalized it is being killed at the same time?

RC: Sure, but I think what we mean by “professional” has changed over time. Obviously, it means making enough money to sustain the practice, but being a professional artist or musician in 1970 looked a lot different from what it might mean now. Whatever the larger cultural mores and economy are at the time will determine what professionalism means. And there have been eras where there’s been a larger commercial embrace of challenging ideas, and I don’t think that we’re living in such a time now.

CKE: The professionalization of creative work reminded me of Poser since it addresses how images and implicitly marketing strategies seem to be more important than the actual content.

RC: In a way, I guess I felt some irritation with the dominance of PR strategies and mood boards in how music is handled today. But it also led to this question, a really stupid but necessary question: What are we even talking about when we say “music” at this point? Especially living in Berlin, where there is such an enormous music industry, artists are so obsessed with their image, their visual output. If one were to flatten the overall output of a popular musician or band, so little of it would have anything to do with the sound they produce.

I started thinking about this during years of living in Berlin, which is covered in promotional posters for new albums or tour announcements for artists I’ve mostly never heard of and rarely feel compelled to look up. At some point, I began to imagine that these posters and whatever they promoted were fictional, they were simply cheap visual compositions designed to propel an idea of popular music forward with endless combinations of signifiers: A rave flyer with black metal fonts, a bedroom pop album release event with a photo of a band dressed in grunge attire, a poorly screen printed flyer for a punk show that looks like it could have happened in 1985.

If all these tropes were freely interchangeable, then it seemed like there was so much work to be done beyond going into a rehearsal studio to write songs. It dawned on me that a band is a kind of readymade, a gestalt, and what’s more, that images might be more important than music in order to create one. Eventually, all these questions became loud enough that I had to seize on them somehow. And maybe an unpopular opinion, but I think experimental music has largely failed to address the conditions of popular music, at least recently.

CKE: It also seems to be about the disconnect between the creator and the product. This reminded me of the K-pop industry and how it’s basically a factory where you’re artificially producing bands. But also thinking about the development of YouTubers or influencers who have no background or genuine interest in music or music production and just use Autotune.

RC: People bring up K-pop a lot in reference to this work, even if there are no visual or sonic similarities, nor is it really a reference point for me. I would love to know how many people are behind the production of a single BTS video. There is a serious industry and money behind this kind of work. It is dependant on an enormous media infrastructure.

I’m just an artist working with my friends and people I admire—people I want to bring into the project. It’s happening on a really small scale. I have the freedom to be as serious or unserious as I want, and I can’t really say I’m trying to be a star—I would hate to be. After all, I’m not a member of Poser. I’m just trying to be a steward of this thing I made and, hopefully, derive meaningful work from it.

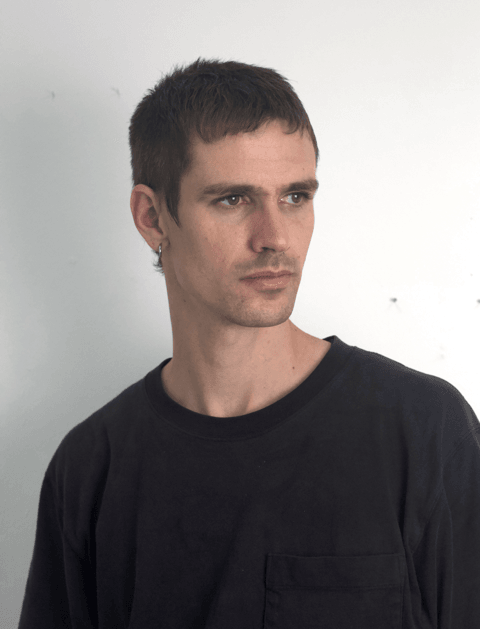

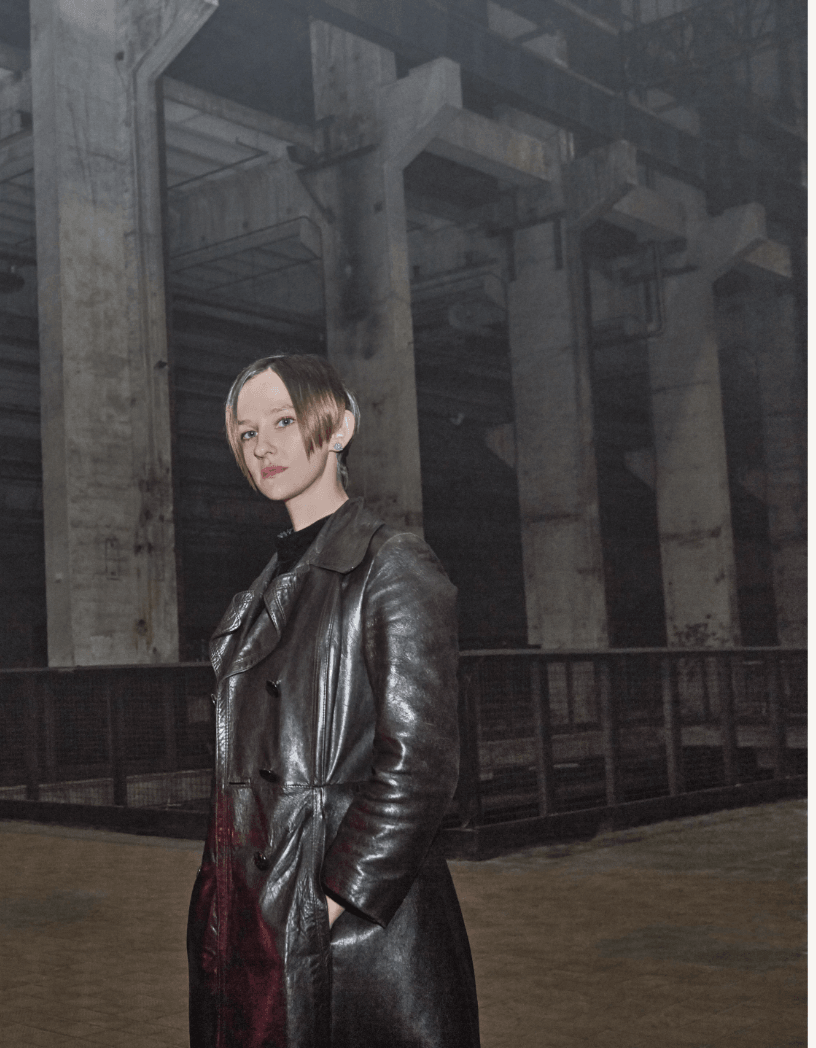

Reece Cox, Ecstasy of Vigilance 01 (left) & Ecstasy of Vigilance 07 (right), 2023. Silkscreens on 300g paper, 100 x 70 cm (39 x 27 inches). Courtesy the artist

CKE: The project also raises questions of authorship. What do you think about ghostwriting?

RC: Art, music, and every other creative discipline have had ghostwriters for centuries. Just go to the Gemäldegalerie, for example. There are paintings attributed to the studio of Rembrandt and it’s unknown if he ever even touched some of them. It’s long been a condition of artistic production, at least on a large scale. The ghostwriter is a sort of black box between the author and the attributed output. I’m interested in that black box: the mining of an author’s style, the inherent but deliberately obscured problem of authorship. With Poser and many projects I take on, they’re somehow about what is unseen, trying to figure out how something works.

CKE: How do music and image-making relate to you? Is a performance always the base for a flat image?

RC: For years, I felt a strong intuition that I wanted to deal with sound and image, but I wasn’t sure what that meant—whether it was a problem of culture, an interest in perception and phenomenology, or something tied to economy and culture. I eventually began to understand that popular music, with its reliance on image and distribution technologies, is an excellent mirror of larger changes in technology and culture from the post-war era to today. It’s about much more than music.

I had been trying to steer my practice back to painting or image-making for a while, mostly unsuccessfully, because I had accumulated all these interests and questions through years of working with sound. When I set out to stage the first Poser performance, I did so with the intention to build an archive of source imagery, but I wasn’t sure what I would do with it. The performance sort of secretly served as a photoshoot, but I wasn’t sure what that would mean yet.

After the performance, I looked at my photographs and those taken by the professional photographer the gallery hired, and it immediately became clear that they were useless as anything other than documentation. At first, it felt like a failure, but it dawned on me later that all the Instagram stories that the audience were sharing was a far more interesting output in terms of images, so I began making stills of all these poorly recorded and compressed images and videos. The audience’s participation in a concert is as important as what happens on stage—it’s part of the gestalt. So, naturally, it made sense to pay attention to what the audience was seeing and how they could associate themselves to the work by sharing it online. Somewhere in there, the black box appears again.

Reece Cox, Untitled 00, 2023. Silkscreen on 300g paper, 100 x 70 cm (39 x 27 inches). Courtesy the artist

I’ve been screenprinting since I was a teenager, making bootleg patches and t-shirts of bands my friends and I liked, and I had an intuition that this medium might serve me better than painting. I found a public print workshop nearby and started producing as much as I could. It instantly clicked.

I love this medium because it allows me to deal with problems of authorship, especially since I’m appropriating other people’s images of my work. I can approach problems of photography without ever needing to pick up a camera. At the same time, I can deploy painting techniques but I’m not quite painting either. By the time a performance is finished and I’ve collected whatever images I want, I finally feel like I can go to the studio and get to work, as if the rest was just preparation. I’ve done what I needed to do to generate images and can finally make art. It feels like alchemy.

CKE: You seem to use all these different mediums quite holistically.

RC: I certainly hope so.

CKE: I read an interesting post by you in which you wrote that sound is much greater than what music permits and that the arts have generally been rather lazy in providing space for its potential.

RC: When I wrote that, I had a very specific range of interests and questions I was trying to speak to. Music depends on sound but sound itself is indifferent to music.

Then there’s the category of sound art, which is a term I don’t really like—especially the way that it gets thrown around today. To me, it’s something that happened maybe in the 1970s and describes a moment in art history. It’s not that sound is no longer a viable artform—of course it is—but the term feels anachronistic to me. For example, if someone described themselves as a pop artist today it would seem ridiculous.

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

Related Content

An Orgy of the Mind With Charlie Fox

Where Does The Puppet End And The Human Begin?

Harry Nuriev’s Critique of the Industry

Hajime Sorayama: What I Draw Are Human Beings

Art World Resorts with Alex Flick

The Split Between the Self and Its Image: Jonas Wendelin

Jan Vorisek’s Devotion Strategy

Beautiful Aliens: KLÁRA HOSNEDLOVÁ

Reality TV as a Sociological Analysis: JAMES BANTONE

Twisted Femmes: ANNA UDDENBERG’s Uncompromising Sculptures

Louisa Gagliardi's Liminal Spaces

CATERINA BARBIERI’s Landscape Listens