The Split Between the Self and Its Image: Jonas Wendelin

|Claire Koron Elat

“I was drawn to how this split between the self and its image is not just emotional or psychological—it’s embedded in the way we view our surroundings, even in the technologies we use.” For artist Jonas Wendelin, technical evolution and its relationship to social organization and communication is at the core of his work. On the occasion of his inclusion in 032c Gallery’s recent exhibition “Do You Like Me? Do You See Me?”, Claire Koron Elat spoke to Wendelin about art as a spectacle, contemporary ruins, and our attention economy.

Directed by: Alma Leandra

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: You’re currently showing new sculptures in our gallery show “Do You Like Me? Do You See Me?”. Before we get to the works, what do you associate with the exhibition title?

JONAS WENDELIN: The title sounds... needy. It’s asking to be accepted and for attention. It seems to be referring to an exposed element of the contemporary self. The images of ourselves are very much out there, constantly observed, and always on display. There’s this inherent division between who we are and the image of ourselves that we project. When thinking about what to show for this exhibition, I was drawn to how this split between the self and its image is not just emotional or psychological—it’s embedded in the way we view our surroundings, even in the technologies we use. We are simultaneously operating in all those fragmented realities, it’s almost like a collective psychosis.

CKE: Looking at your sculptures Lucid Ruins, many gallery visitors assumed that the structures are either made of ice or silicone. Can you explain the material process?

JW: I describe the objects as ambiguous, something that resists immediate understanding. They invite investigation. Once one is confronted with something unclear, questions arise, and a conversation can begin. A bit like the attention economy we’re placed in, also in the context of this show. But there’s something interesting about not giving everything away, you really have to look at the piece in order to understand the making of it.

Technically speaking, the process involves a vacuum forming gravel arrangements from broken concrete bricks. I am left with a thin transparent membrane of acrylic glass in the shape of the constructed ruins. These forms are placed in narrow stainless-steel water basins, and the water is suspended inside them by atmospheric pressure, taking on the shape of the sculpture above the surface. The water is basically taking the memory of the ruin itself. The volume of the sculpture is greater than the basins so there’s much more water throughout the piece than what originally fits in the basins, which is giving the works a sense of equilibrium, seemingly on the verge of collapse.

I like the idea that if we are in a closed system—like a gallery space, for example—and we would all take a breath at the same time, the atmospheric pressure that holds the water in place and suspends the vacuum within the sculpture would drop, and then would spill over the basins and flood the system itself. A collective action taking down the system so to speak.

Jonas Wendelin, Lucid Ruins, 2024

CKE: You also studied under Olafur Eliasson. To me, that feels connected to the way you approach your works, which all seem to have a scientific and technical approach.

JW: Certain periods come with certain questions, and yes, water happens to be a shared material in this case. I’m not necessarily very interested in the phenomenological aspects. I’m generally interested in the way we understand our place in nature—how our evolution is inherently connected to raw materials and the technologies they inspire. Maybe our ideas are already present in them and we are just the agents carrying them out as part of a global consciousness, even though we all operate under the impression of being free agents.

With these sculptures, I’ve been exploring how the ruins of our time—those left by technology and extraction—fuse with the natural world and reshape how we perceive our histories and environment. I think there’s a false dichotomy between what we consider “man-made” and what we see as “natural.” In a closed system, nature doesn’t categorize the same way we do.

I have a background in ceramics, one of humanity’s earliest technologies. Clay itself is a byproduct of erosion. The water trickles down the mountains and ends up in riverbeds called alluviates. These highly fertile grounds are the first settled grounds of humanity. So, where do we draw the line? Where does nature end and culture begin? Isn’t a copper mine digging into the earth architecturally reminiscent of the amphitheaters preserved? And aren’t the ephemeral digital architectures drafted from our devices made of just those same materials generating the stages on which we all perform?

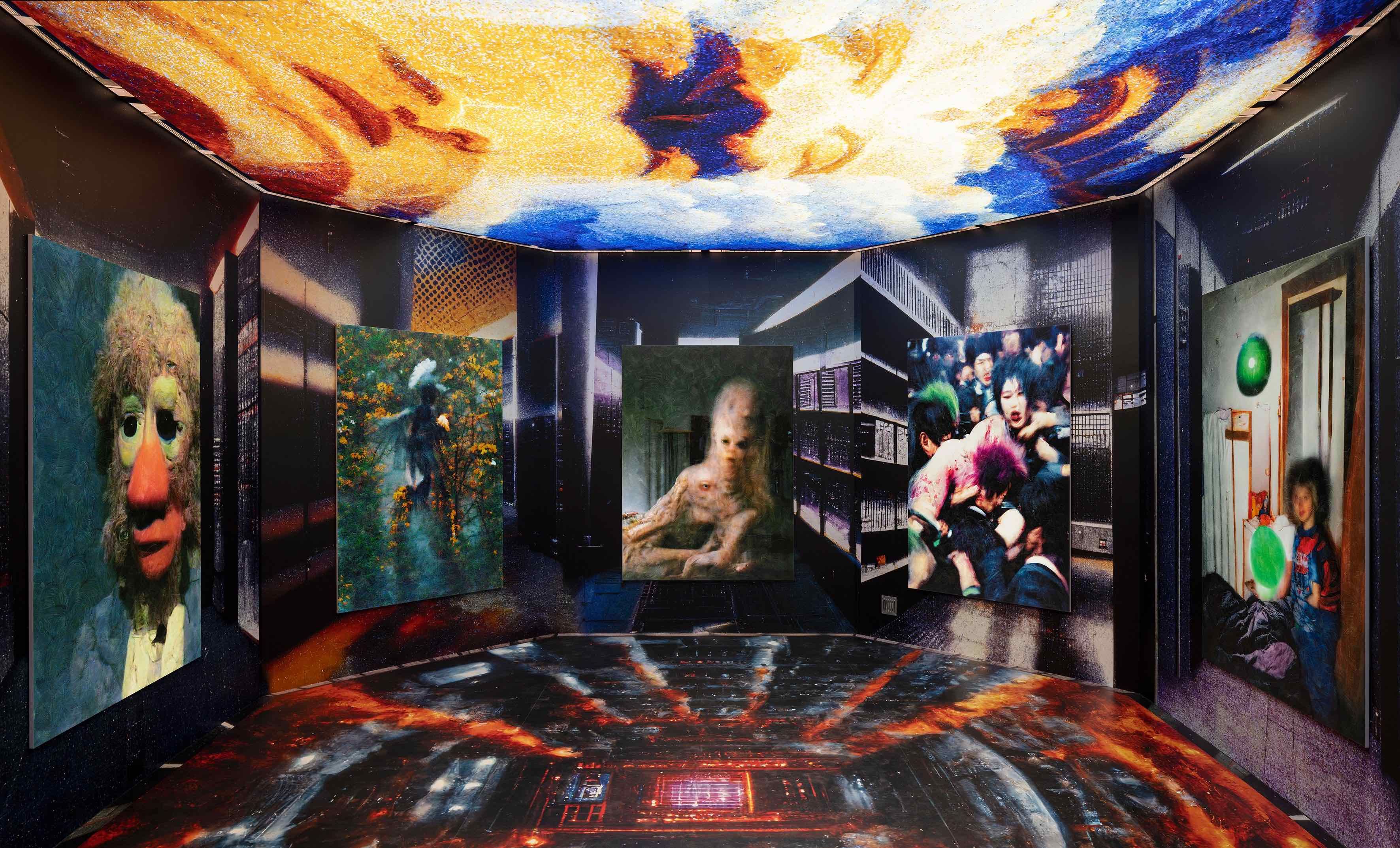

Jonas Wendelin, ONLY, Installation views, DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM, Berlin, 2019

CKE: When you mentioned that you want people to look at the work extensively this also raises the issue about our attention economy. Nowadays, art is being turned into a spectacle or becoming entertainment—and the same goes for fashion. You no longer look at the objects but at everything that’s orchestrated around it.

JW: Exactly. These platforms where voyeurism and the attention economy drive our behavior are physical spaces, even if they feel intangible. It’s like a layered yet very ephemeral space. So, my intention was to create an ephemeral ruin.

Take this conversation, for example. I’m sitting here with my phone, and we’re speaking across a space that exists between us. But the phone itself is made of very concrete materials—copper, gold, platinum. So while we operate in this polished, fast-paced digital world, there’s this underlying detachment from the physical realities—the extraction, the ruins—on which this space is built.

CKE: Thinking around the notion of the ruin, do you explicitly distinguish between historic and contemporary ruins?

JW: Ruins in the historical sense can be a method for us to look at our past and understand where we come from. The ruin I am working with is something that’s happening more in this moment. They’re tied to the architectural spaces we inhabit today but are somehow hidden.

In many ways, the world is already in ruins. Entire cities, warzones, and extraction sites lie crumbling beneath the surface of modernity. We know they exist, but we’ve become so adept at compartmentalizing that they just flicker past us as images on a screen. Every swipe turns these realities into ruins—something distant and abstract, buried under strata of information.

Jonas Wendelin, IMPATIENCE OF PERMANENCE I, 2024

CKE: Do you think there could be a way to be more conscious about it?

JW: There has to be. But it’s a collective effort, right? We are definitely craving healing, and art as technology can maybe facilitate that to some degree or simply allow for perspectives on it.

CKE: So you think this kind of reflection should happen through IRL communication?

JW: It’s our culture, right? It has to happen in all layers simultaneously. Online culture is still young and trying to figure itself out. It reflects our emotional landscapes in a very raw, sometimes homogenous way. But we also have to understand the heritage of our communication—even in something as simple as an emoji or an avatar, there’s a whole history encoded there.

The challenge is to become more conscious of how we engage with these systems and how they consume us. We’ve reached a point where technology is not just something we use—it’s something we’ve evolved with. It is something we are physically. It does make reality feel increasingly abstract.

CKE: It’s also impossible to not participate. If you didn’t, you would not only be considered weird but would also not be able to work to a large extent, especially in the creative industry. And your work also addresses how these platforms that are seemingly intended to create communities, or to make us closer to each other, actually lead to forms of division and voyeurism.

JW: That’s the paradox, isn’t it? These spaces we communicate in are deeply tied to performance—economic performance, personal performance. And yet, the very spaces we build are extracted from our own participation and our habitat. It’s a strange circular dynamic where we’re both the architects and the ruins.

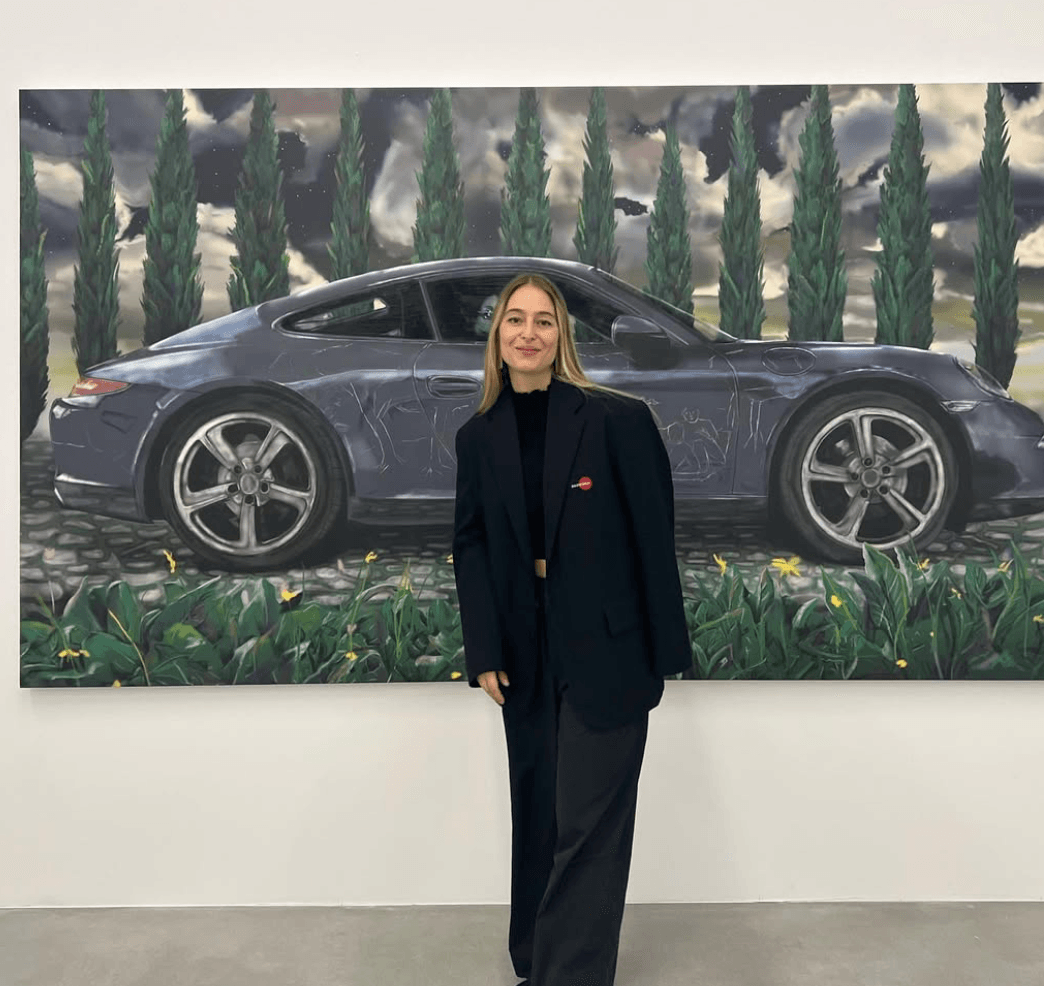

Photo: Alma Leandra

Credits

- Text: Claire Koron Elat

Related Content

Do You Like Me? Do You See Me?

Louisa Gagliardi's Liminal Spaces

Abusing Technology with Kim Gordon

Primal Beauty Advanced Technology

The Undercurrents of Materials: CUDELICE BRAZELTON IV

Other People: SER SERPAS

Selling leggings at artmonte-carlo: MOHAMED ALMUSIBLI

Finding Romance in the Grotesque: JON RAFMAN

Erwan Sene’s Sonic Odyssey