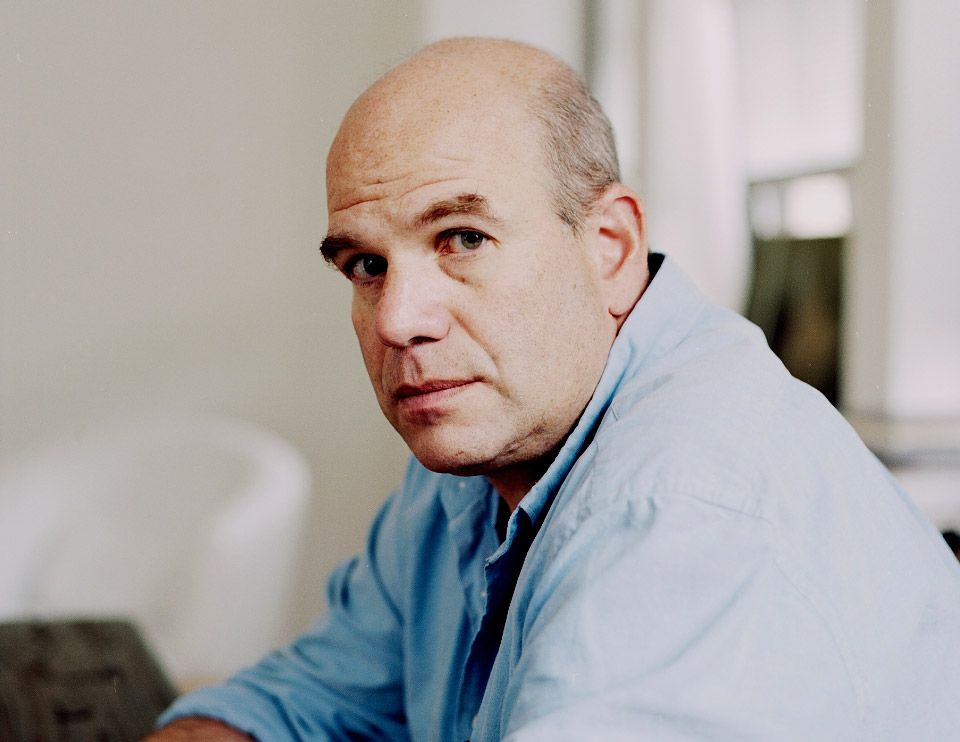

Reality TV as a Sociological Analysis: JAMES BANTONE

|Claire Koron Elat

Is reality TV more influential than visual art? Considering the amount of people who engage with it as a quotidian form of entertainment in comparison to those who make an exhibition visit that might happen once a month, one might endorse this (almost blasphemous) idea. But perhaps reality TV can also function as the basis for critical (art)work that analyzes the cultural and social status of current society through “trashy” behaviorisms exhibited in trash TV.

Artist James Bantone started watching the TV series Love & Hip Hop—a show that started in the early 2010s in New York, documenting the lives of hip hop and R&B musicians and managers—when he was a teenager growing up in Switzerland. At the time—and arguable still today—there was little representation of a Black and queer scene in the European country. So, for Bantone, the show functioned as an escapist vessel.

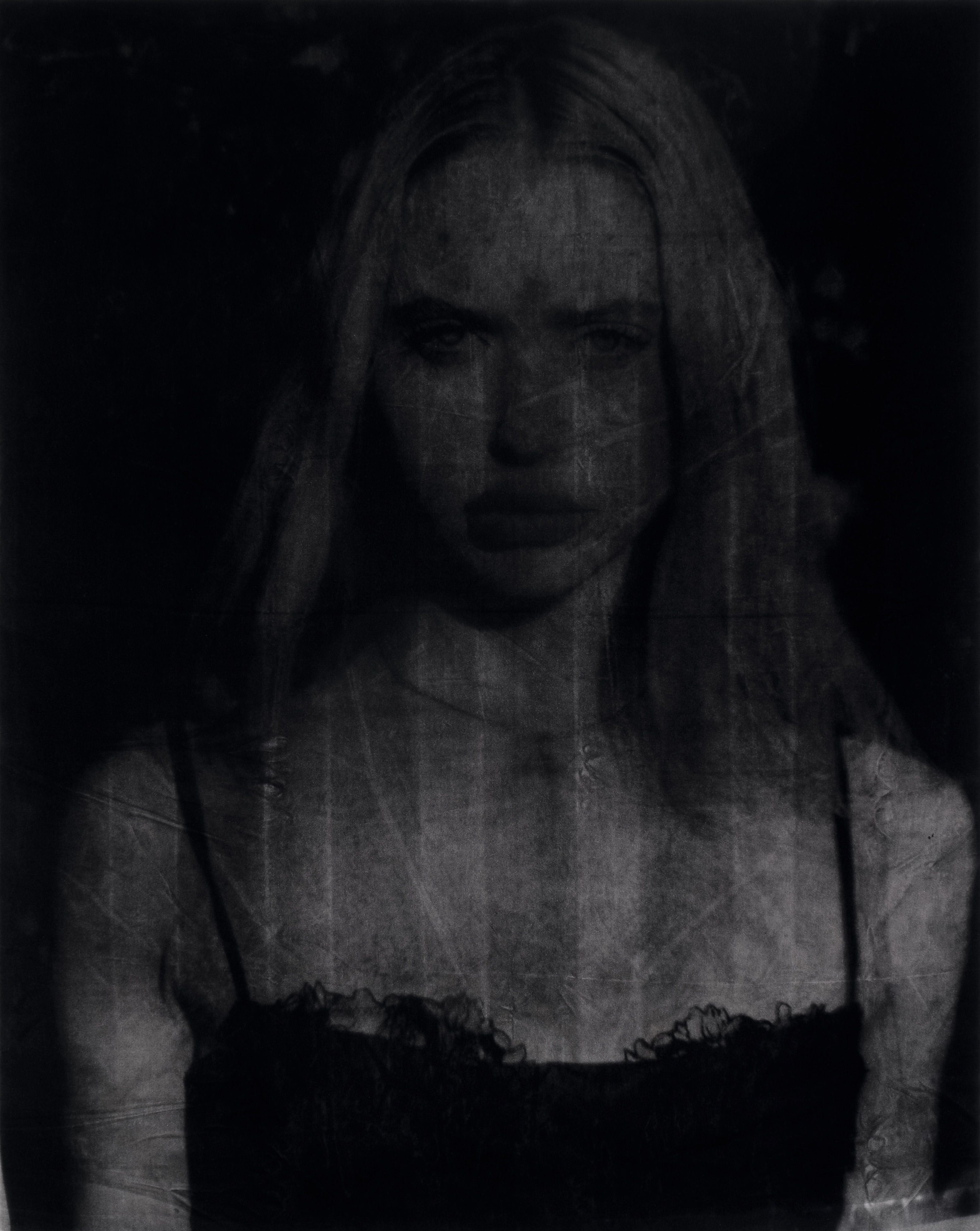

Today, Bantone’s work—comprising sculpture, painting, and photography—is interested in speculations around what radical Black aesthetic forms that are not appropriated by whiteness could look like. Exploring the performative aspects of mimesis as well as the production of art itself, Bantone asks whether everything we do is a form of performativity.

CKE: Your work is visually at the intersection of art and fashion. Previously, you said that fashion is ultimately a form of performance. This made me think about the development in the industry where fashion is no longer thinkable without an entertainment factor.

JB: This question opens up what we define as performance and what we define as entertainment. I think performance can be entertaining, but it doesn’t mean that it’s designed to be entertaining. And there is a performance aspect in fashion in the sense of it going beyond the work of the garment itself. Also, there’s the definition that it gives to the person wearing the garment. It puts you in a certain category and you’re being perceived in a certain way.

Do you see performance as entertainment?

CKE: I think entertainment always includes performance. But performance is not automatically entertainment. If you perform a dance piece in front of a large audience, performance is closer to entertainment than if you perform the act of painting alone in your studio. So, it’s more a question of context.

JB: I have a difficult relationship with performance. I’m not a huge fan of performance art. In a way, everything is a performance—even the production of art itself is a performance. Even the white cube in itself is a performance because it gives the setting of this idea of what is or is not art, or what is fashion and what is not fashion. It’s defined by the context, but the performativity of the context situates the work or the action.

CKE: Have you ever done any performance pieces?

JB: I recently had an idea for a new work, which I wanted to be more performative. And my previous video works were quite performative. One of my very first video works consisted of reenactments of scenes from Love & Hip Hop, a reality TV series. I was directing performers and friends of mine. The format of people reenacting scenes from reality TV was very famous on social media at some point. I did the same but put the performer in a studio space, making it as minimal as possible to focus on the gestures, and how people were moving in the space.

CKE: Why were you interested in reality TV?

JB: It’s what I was drawn to before art. But when I realized I can make art through the things that I’m interested in, which was reality TV at the time, that’s when I started doing art and had fun doing it.

I mostly watched American reality TV shows, and I was amazed by the whole performance of the people in these shows. It was a big cultural shock. I’m Swiss and there didn’t really exist much representation of the Black community in Switzerland. It reminded me of the queer scene in New York, and the friends that I had around there. That’s how I started to be absorbed by these shows. And I sort of aligned with the way that the people in these shows were acting.

CKE: The social aspect of the art world almost feels like a reality TV show. A show that takes place within reality with real people, but you still have some fictional elements or elements where it’s not certain if they’re real or not. I think as soon as something becomes entertainment, it’s not authentic anymore. You’re trying to do something in a specific way because you know that you’re being perceived and are even trying to evoke certain reactions. Do you think there is a big difference between reality TV shows today vs those of the past?

JB: I feel like these shows were more entertaining in the past. Now there are certain things that are way too problematic in order to enjoy them. I was always attracted to shows such as Love & Hip Hop or Real Housewives. But these new shows such as Love is Blind or Too Hot to Handle are way too much for me.

CKE: I think you can watch them in a critical way. The shows function as an analysis of the current state of society. And they have become almost crucial in defining culture today, simply because such a large amount of people watches them and engages with them through memes and discussions on social media. I think that this is comparable to the influence that fashion has on society. In the end, it’s probably way more central and influential on society than art. There is only a small fraction of people who engage with art every single day, but everyone does so with fashion.

JB: Definitely. Everyone gets dressed. And consciously or not, fashion does position you in a certain way. Fashion has to do with the status that comes with wearing certain things, and into what category it puts people. So, I agree that fashion has a much broader impact on society than art.

CKE: You were also doing commercial work at some point, right?

JB: When I started with photography, I was attracted by social or documentary styles. Little by little, I became more attracted by fashion. Then I did jobs for young designers in Switzerland, and then more commercial jobs. I was never doing it on a super high level, but I was working in that industry.

It influences my practice as an artist. I really believe that there’s not much difference between fashion and art. For example, some editorials are almost high-end art pieces.

CKE: Was the commercial work rooted in an interest in shooting editorials or was it for economic reasons?

JB: The economic point was a really big thing for me, because I don’t really come from an art background. I think I didn’t really understand what art was at first, and I was not so interested in it. When I applied to the art schools in Geneva and Lausanne, they accepted me for Fine Arts in Geneva, and for visual communication photography in Lausanne. In Geneva, they asked me, “Are you ready to make art as an artist?” At the time, it freaked me out. So, I went with photography studies. For me, it was really important to earn money.

CKE: Do you now have a greater sense of security in the art that you’re making?

JB: I gave up on security a long time ago [laughs]. I’ve always known where I want to be, and I know the things that I have to do to get where I want to be. I don’t want to sound cocky, but I’m more ambitious in that way. Having a gallerist is definitely a game changer because it opens doors. It is about the process of how your art is distributed, and how you get to a certain level. But I still wonder, because I don’t know if my art is easy or sellable—or let’s say commercial? I’m still figuring out what the right audience is for the type of art I do. And I’m still learning things about the art market. But the fact that I had a job before doing this allowed me to take on some regular jobs on the side and earn money outside of my art practices.

CKE: I read in another interview that, through painting, you want to make the work less accessible. Can you explain what you meant?

JB: In my work in general, I like to play with ideas of value and representation. For a very long time, I was questioning my position within art. Why I was where I was in this part of my career, and why I had the space that I had. For me, it’s important to play with this idea of what is art, what is not art, and what it is to be an artist of color in Switzerland. What does it mean for me to do photography, sculptures, or paintings. I want to play with all these intertwined situations or positions.

I’m not a painter, I don’t consider myself a painter, and I don’t want to be a painter. It’s the idea of playing with the value of painting. Most of the paintings I have done were related to my sculptures. I don’t want to say they’re beginner paintings, but they are naive. I come from a very selective figurative background, and I want to talk about the same things I talk about in my sculptures but make them more accessible. I’m interested in the social and conceptual aspects.

CKE: And paintings are certainly also a desirable and sellable medium.

JB: It has huge commercial value, yes.

Credits

- Text: Claire Koron Elat

Related Content

Salty, Litigious, Iconoclastic: DAVID SIMON on TV as discourse

“Drama—netic” by CHRISTOPHE DE ROHAN CHABOT

The American Dream Doesn’t Exist, It Never Has

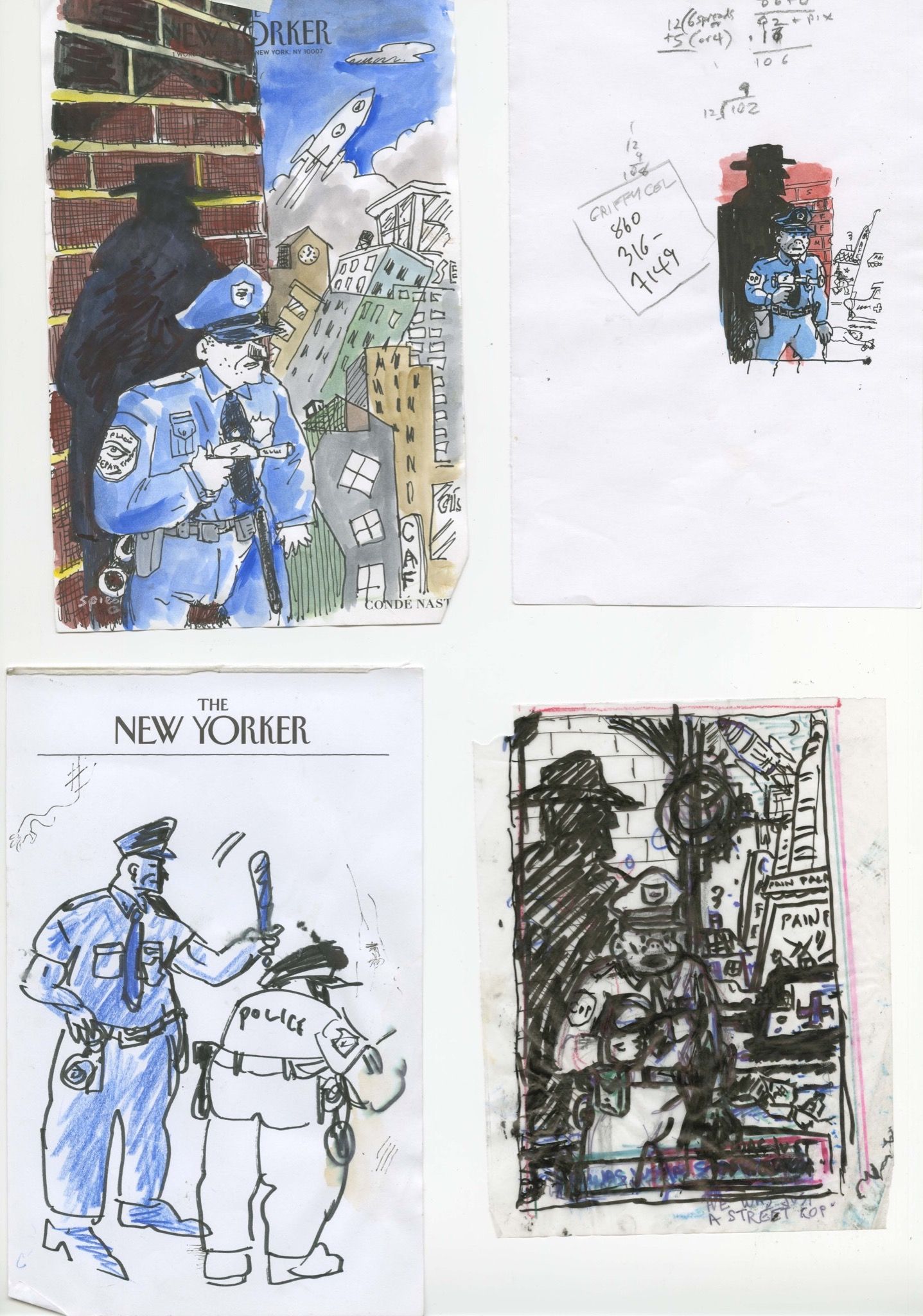

Despair and Dystopia Next Door: ART SPIEGELMAN in conversation with HANS ULRICH OBRIST

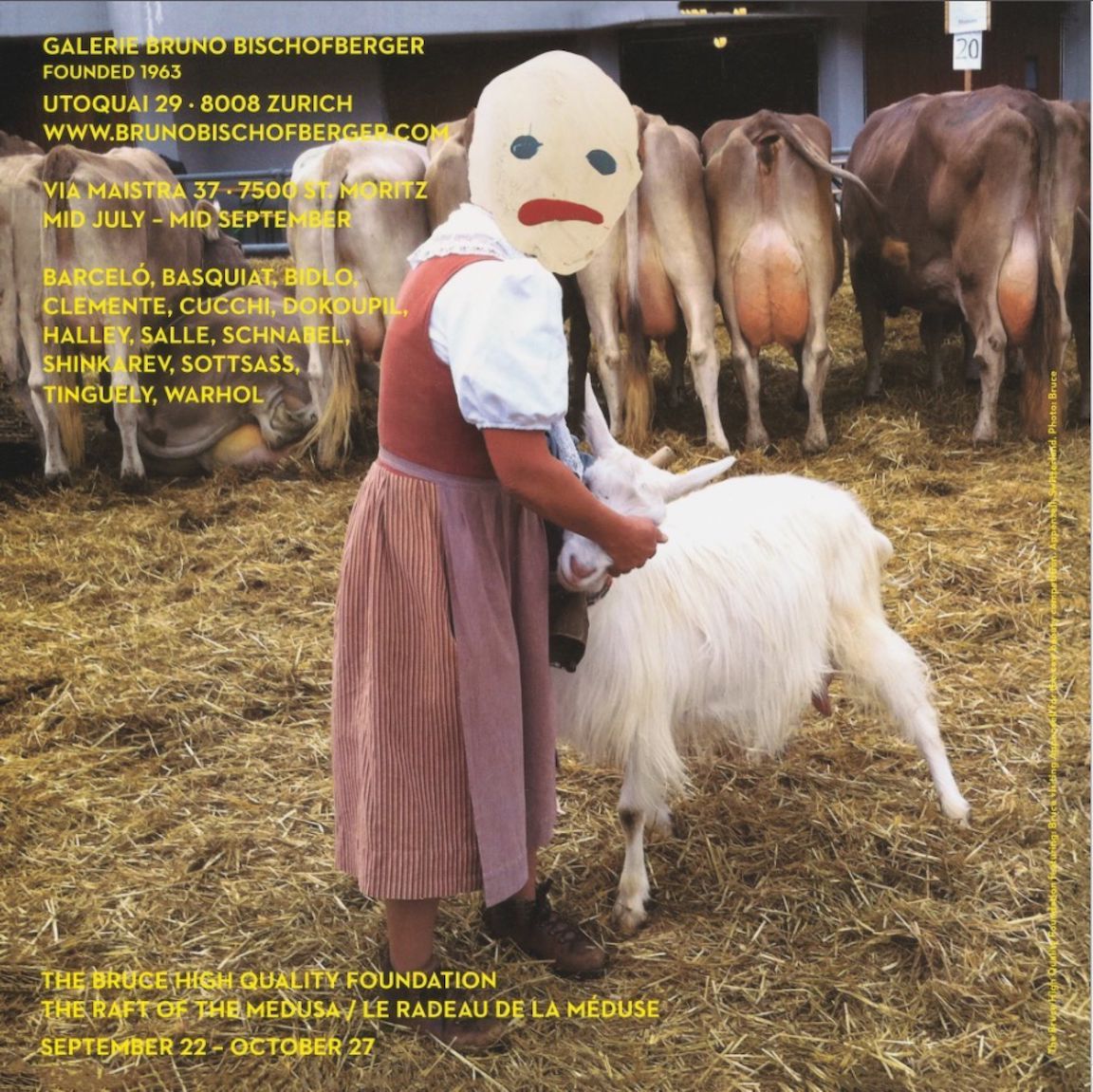

Thus Spoke Bischofberger: Artforum’s Eternally Swiss Back Cover

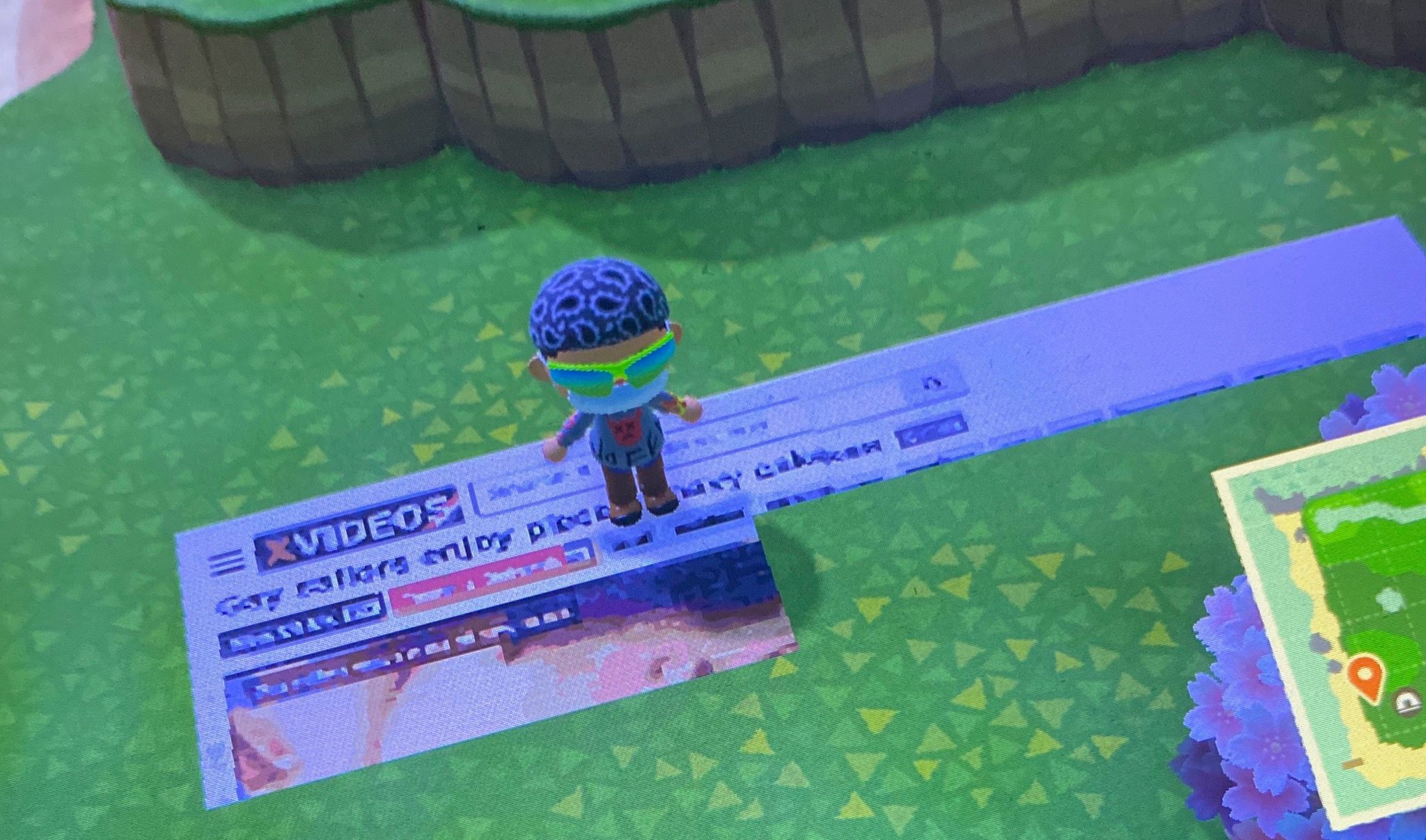

Bring Your Favorite Wade Guyton Artwork into Animal Crossing with MARC GOEHRING

Twisted Femmes: ANNA UDDENBERG’s Uncompromising Sculptures

Artist BJARNE MELGAARD’s Demented SoHo Yard Sale Resurrects a Stolen Sculpture