Louisa Gagliardi's Liminal Spaces

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

Acting as reflections of the artist and viewer, the paintings of Swiss artist Louisa Gagliardi intend to capture internal and emotional worlds while mirroring the rapid developments in technology that shape our visual and social landscapes. Their liminal status—in between digitally crafted and physically constructed—addresses issues of self-curated identities while simultaneously navigating art historical narratives.

On the occasion of her solo show “Whereabouts” at Eva Presenhuber in Vienna, Claire Koron Elat sat down with Gagliardi to discuss why we seem to be more confident when we’re children, cringing over old work, and being forced to be pessimistic.

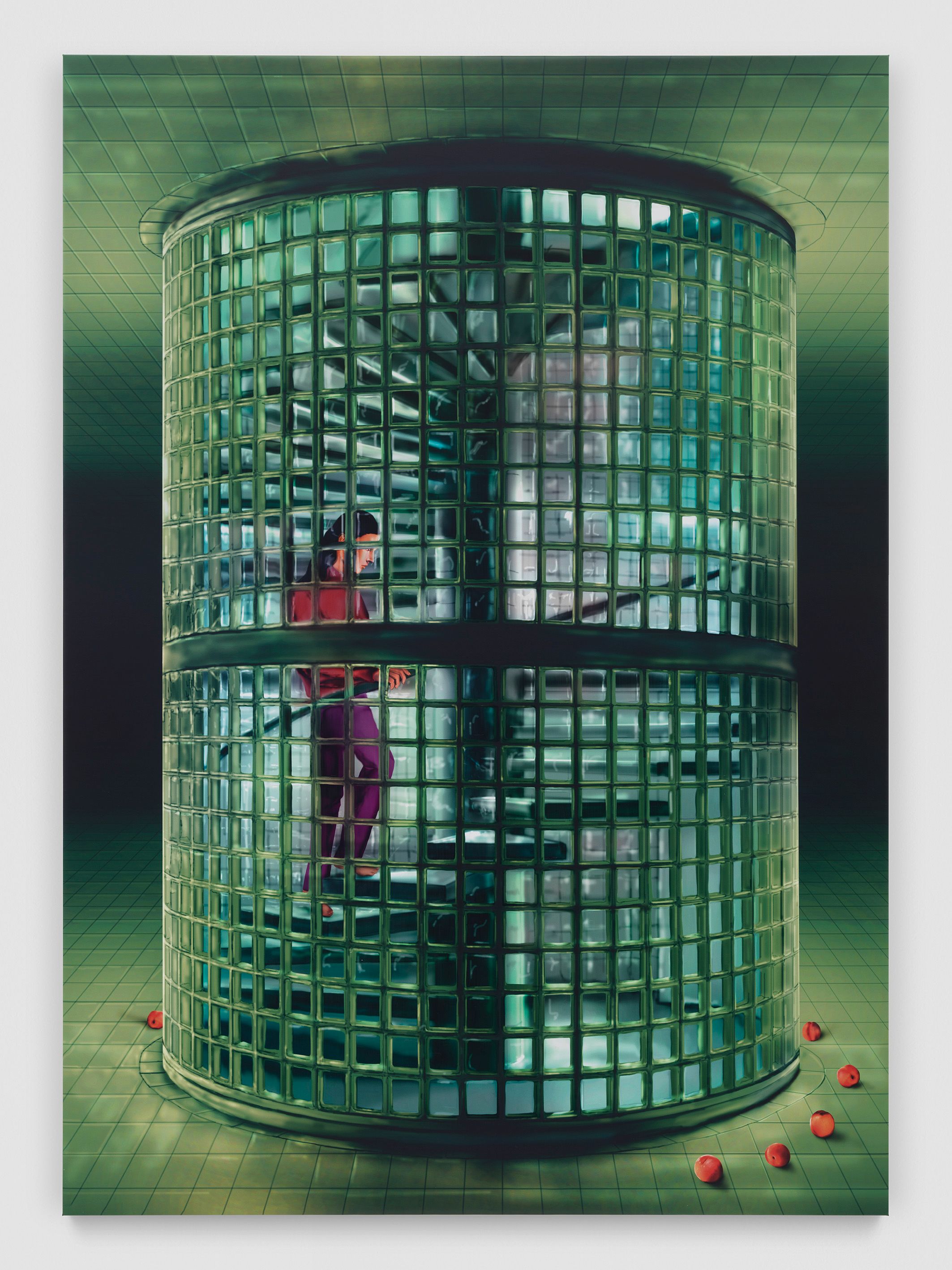

Louisa Gagliardi, Climbing, gel medium, ink on PVC, 2024. Photography: Stefan Altenburger Photography, Zürich. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / Vienna

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: For you, paintings function as a way of investigating liminality. Can you explain this and the ways in which liminality is present materially and theoretically in your work?

LOUISA GAGLIARDI: The show is called “Whereabouts,” which defines more or less a neither here nor there situation. Being 35 years old now, I feel like I’m in this very liminal moment where the number tells me I’m not a child anymore, that I shouldn’t feel like I’m playing grown up anymore, but I still feel like that more often that I’d like to admit. I also think that the beauty of age is zooming out, getting out of yourself, and seeing the bigger picture. Sometimes I miss my 16-year-old self. I was super bratty and confident—the world was at my feet.

Growing up is also realizing how little you matter. It can be very exciting and freeing, but also terrifying. I think imposter syndrome is being thrown around a little too easily, but there is a little bit of that. So, I used a lot of these liminal spaces for this show, such as tunnels and stairs and even a cage because they symbolize this moment. I also feel like a liminal moment is a rite of passage––what you are when you enter and what you are when you leave is different. There is this feeling of being stopped in time.

CKE: It’s interesting that you said you were more confident at 16 than you are now. And this is interesting to think further around the topic of transitions, since as a child, especially as a woman, you suddenly have a moment where you become fully conscious of your body. Do you know why you were more confident back then?

LG: I see two topics in your question. One is about confidence, and you know the saying: “ignorance is bliss,” that was 16-year-old me. And then, if we’re talking about transition, one is about making peace with your body. I still haven’t made peace with my body. I don’t think a woman easily can, society doesn’t quite allow it yet. At the same time, there is a comfort, and discomfort, in knowing how fucked up things are, how your little self is just a drop in the bucket, and you are probably the only one who cares.

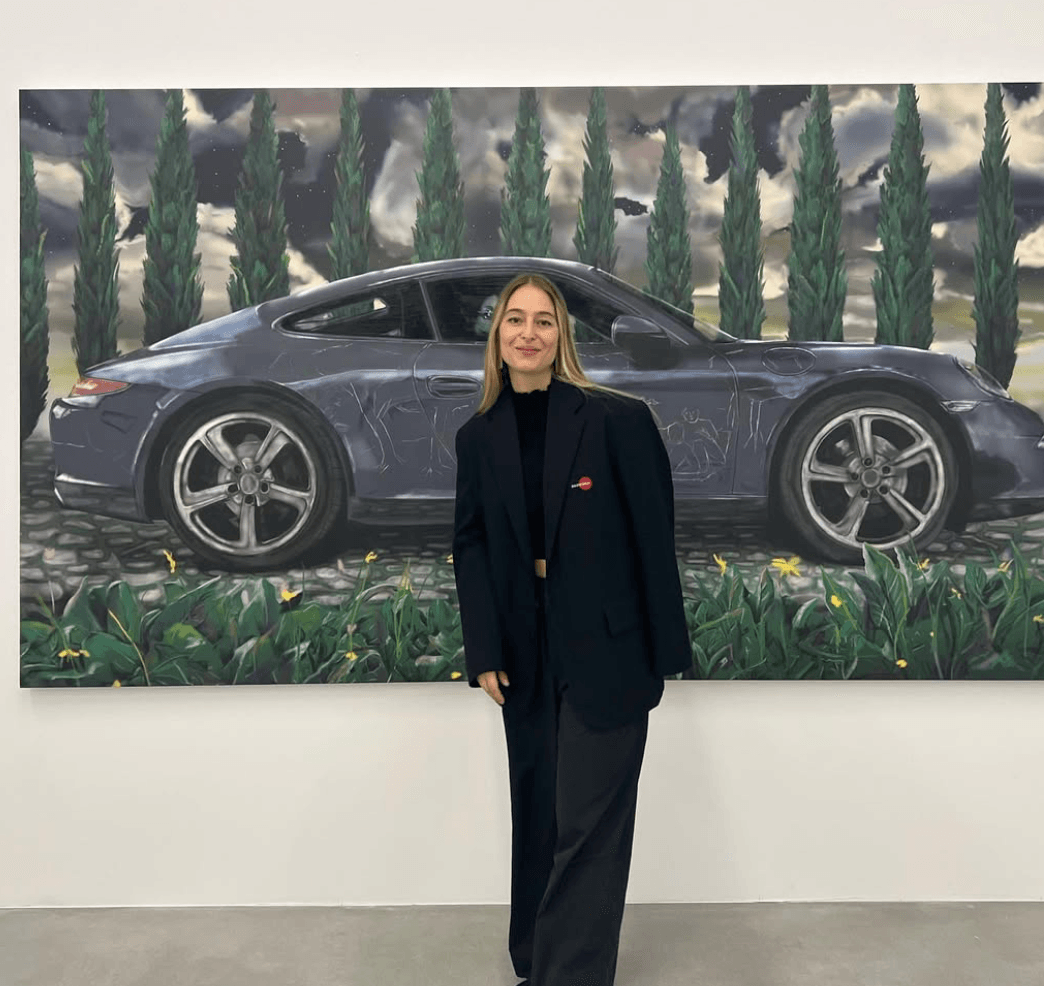

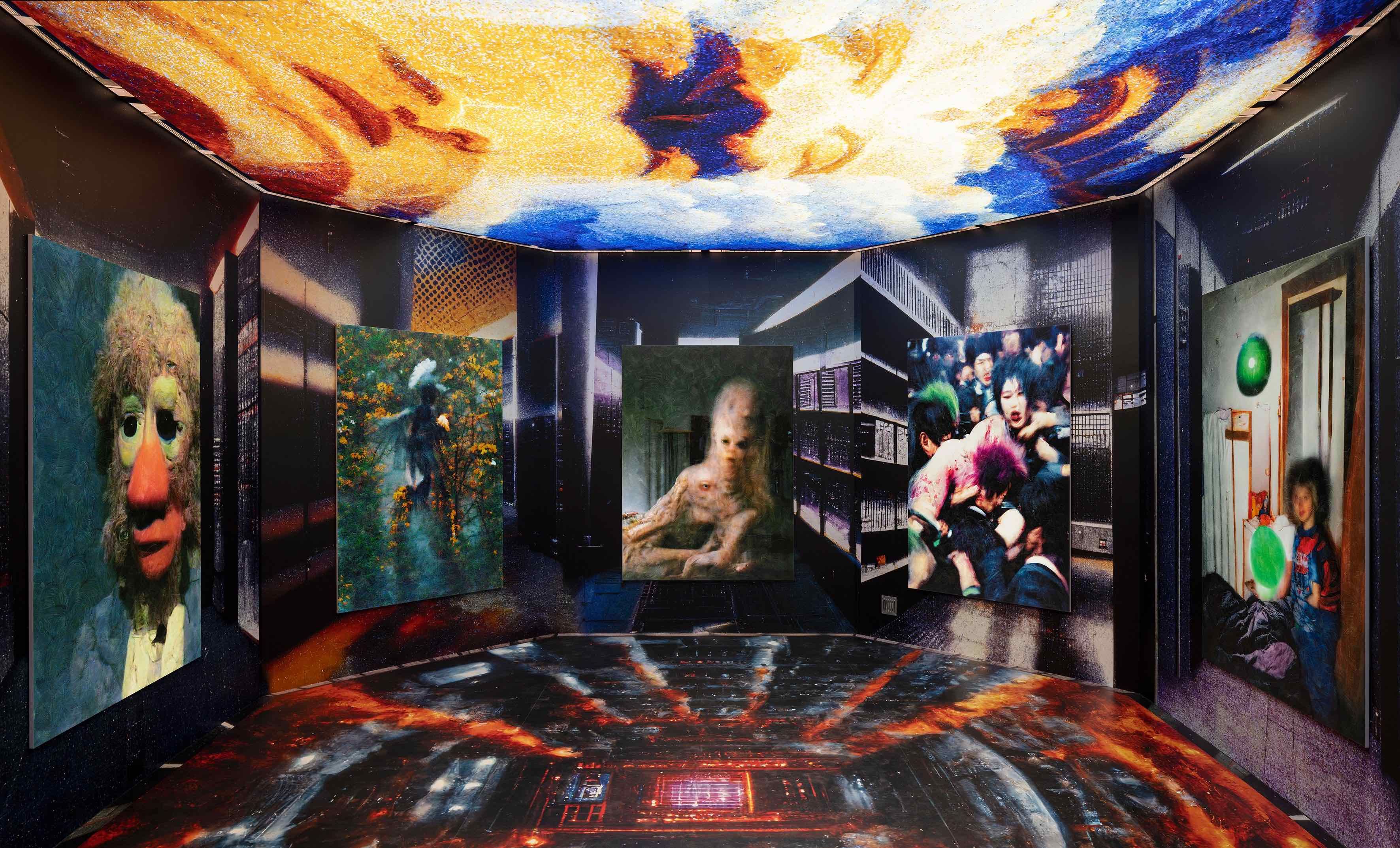

Installation view of Louisa Gagliardi, “Whereabouts”, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Vienna, 2024. Photography Jorit Aust. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / Vienna

CKE: And a large part of that might also be that you have so much access to information nowadays and see how everyone present themselves and their lives online. Do you think online culture has negatively affected the perception of the self?

LG: I’m so glad I didn’t grow up with social media. Instagram came in when I was 25 or something, and so I already was almost fully formed. I had a career already, sort of, and I was feeling good in my shoes. What I love about technology is the fact that you can curate yourself online––whatever the ideal person you want to be, what you normally cannot control, you can control there. If someone wants to live online, I totally support that. I think some people are way happier there, they have found their people online. The outside world is a cruel, cruel world. And so in that way, the internet is a beautiful thing. Let me rephrase that: the internet was a beautiful thing. Unfortunately, like everything else is, we managed to fuck it up. Also, I’m basic, seeing everyone showing their cute selfies and cool lives can give you a lot of anxiety and FOMO.

So, yes to technology and the internet, but social media is a disease.

CKE: Since you work deals so much with the notion of liminality, I was reminded of Jeremy Shaw’s work. He mainly works with video and can induce a kind of liminal experience. Why did you choose the medium of painting to explore this idea?

LG: I’ve always been creative. I always knew that I needed to do something with my hands. Funny enough, I'm working a lot digitally, but I’ve always been an image maker. I’ve always drawn a lot. I created with anything I could find. Unfortunately, I cannot write––I have so many journals and rereading them is the most excruciating thing, especially the ones from my teenager years.

I would like to write a novel, it would be so exciting, but unfortunately, it’s a gift that I don’t have. And I found that the best way to express all this universe that's trapped in my head is with painting. A funny thing about liminality through dancing, since that’s what Jeremy Shaw deals with, is that the nightclub is a liminal space, which I absolutely love.

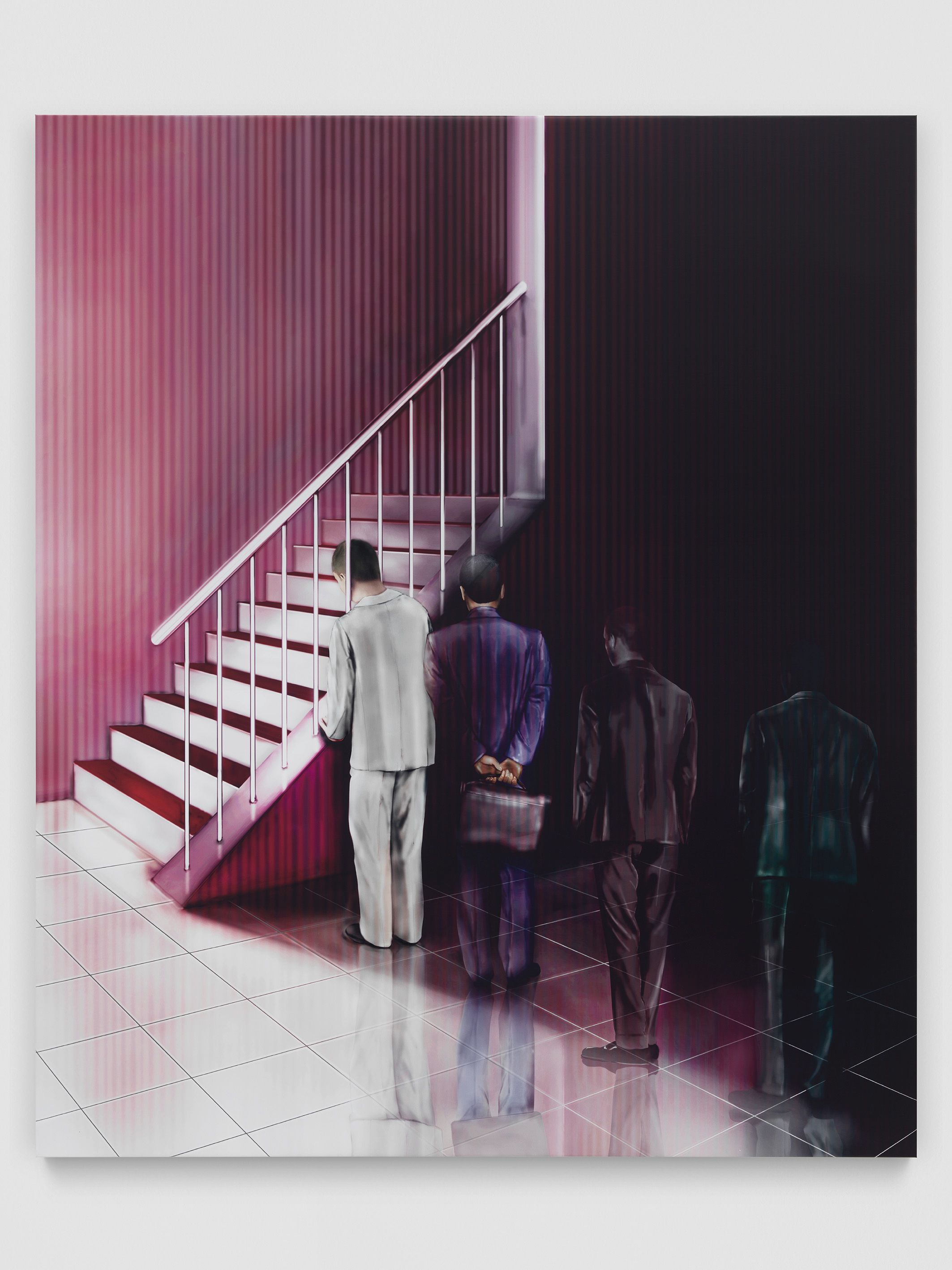

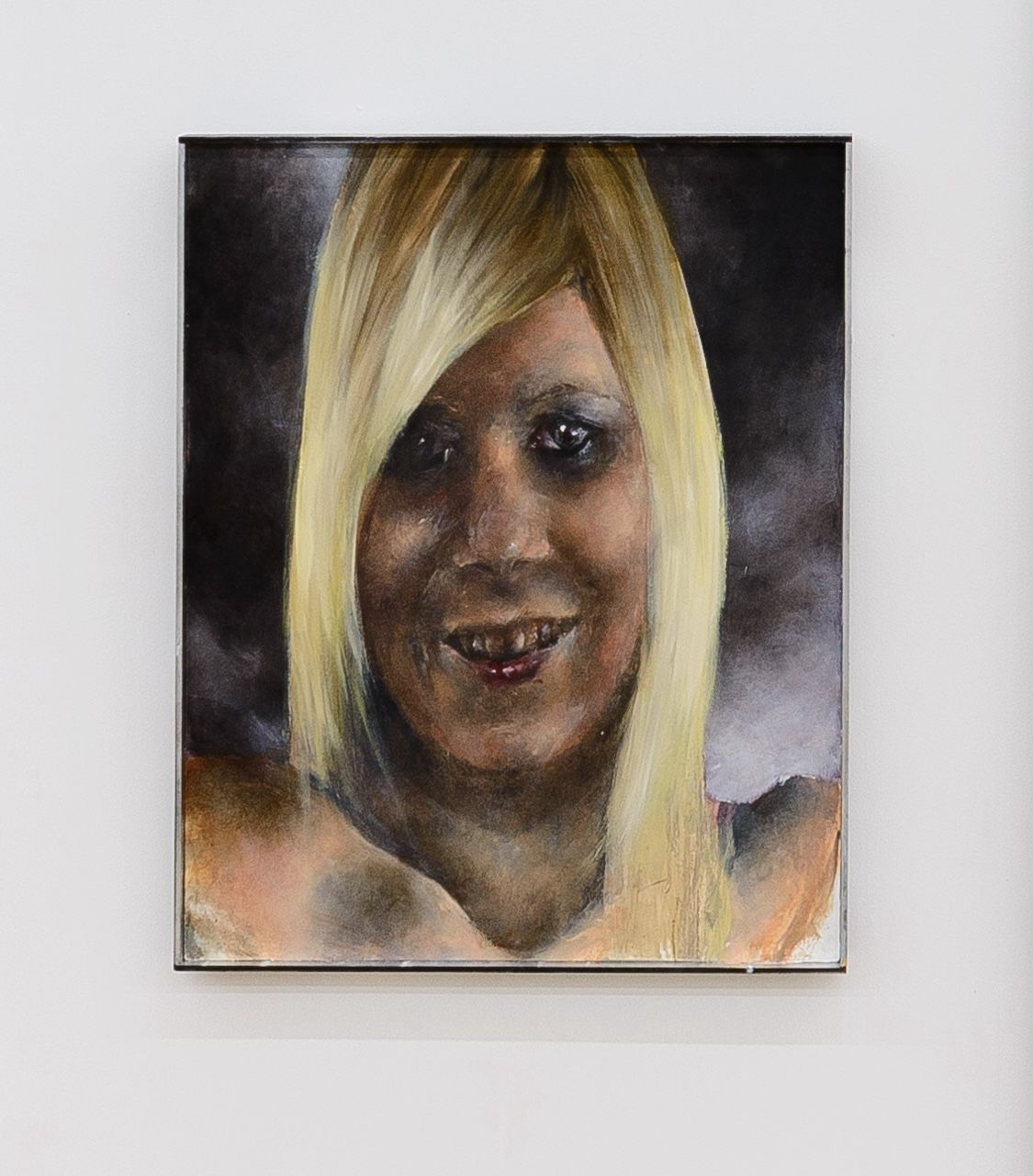

Louisa Gagliardi, Crossing Paths, nail polish, ink on PVC (left) and Voluntary Prisoner, gel medium, ink on PVC (right), 2024. Photography: Stefan Altenburger Photography, Zürich. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / Vienna

CKE: Do you also cringe when you look at older works of yours—like when you reread journals?

LG: Yes. I come from graphic design, and very early on, I was starting to make what I would more comfortably call illustration, because I would never have dared to call myself an artist. Luckily, I had some people that were following my work and who offered me a show in a gallery. So, I was kind of thrown into it, which I’m very, very thankful for. I'm not complaining, but it was scary, because, yes, imposter syndrome is a thing. My first paintings were so emo. And if you know me, I’m a pretty positive and sunny person—or so I’d like to think. I think it was also my way of throwing all this insecurity and darkness into something. So I hope my palette has evolved since then.

CKE: Do you think we’re kind of forced to be pessimistic because the world is so cruel? Being unapologetically optimistic would kind of be a form of denial of what’s happening.

LG: I think it’s absolutely a form of denying as well as a way to cope with it. It’s almost like an armor. Also, coming from Switzerland, I’m really privileged and everything, so I also try to be careful not to take much room to complain, because I’ve received everything. But I still have this sort of insecurity that needs to come out in this way and it’s the thoughts that I don’t dare to say with my words.

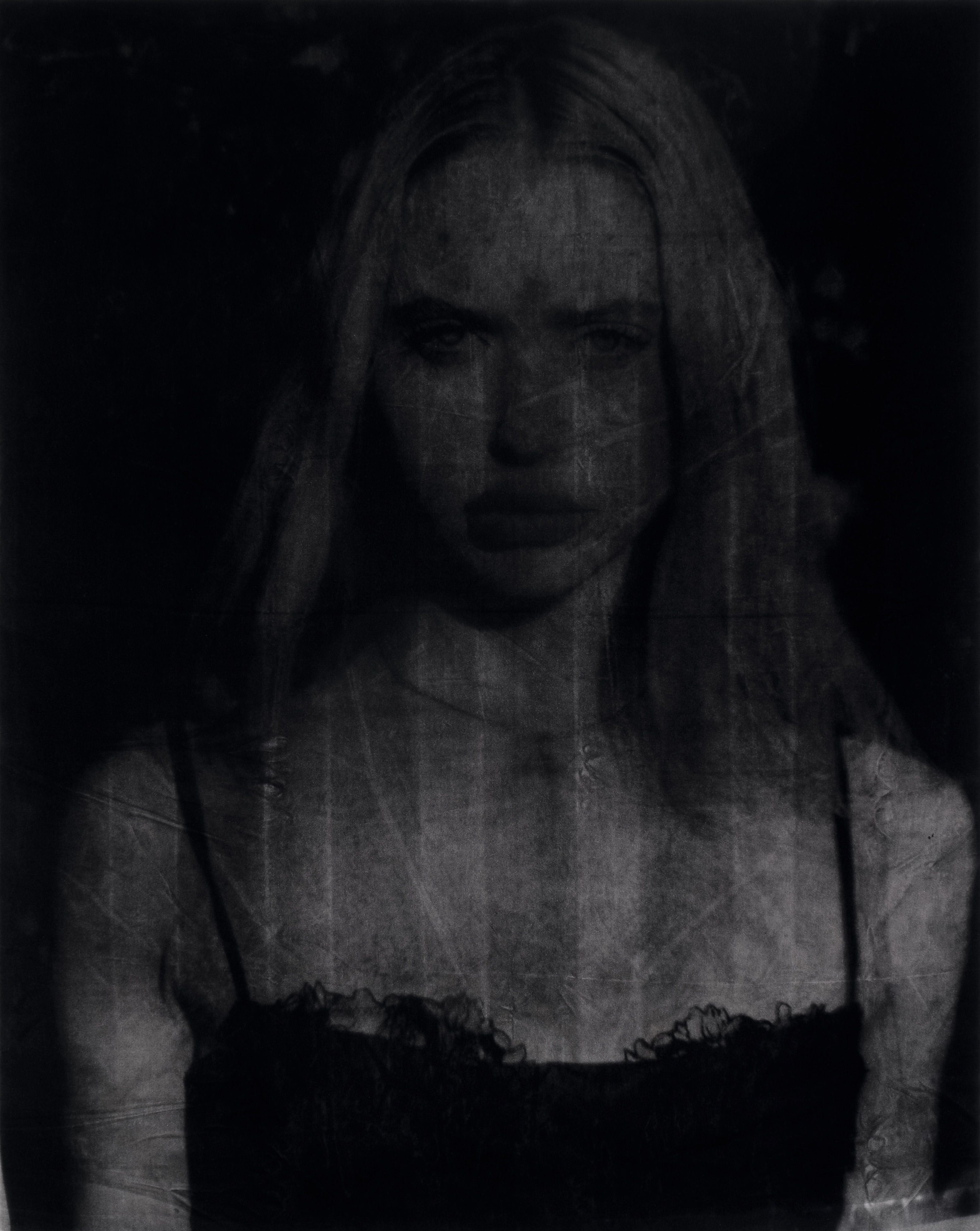

Louisa Gagliardi, Leave of Absence, nail polish, ink on PVC, 2024. Photography: Stefan Altenburger Photography, Zürich. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / Vienna

CKE: You had a clear transition in your practice from graphic design to painting. Was there a specific point where you realized that you wanted to make the switch? And was there a moment where you really felt like, “Now I’m a painter and not an illustrator?”

LG: I chose graphic design because I come from a very pragmatic family background. I come from a small town in Switzerland and my parents are very supportive about what I wanted to do. But I felt like I needed to learn a job. And even as bratty as I was, I was scared, so I went to study graphic design. After I graduated, I started working for different agencies, and I was like, I cannot do this for the rest of my life. It’s such a long feedback process, having a boss, a client, etc. My ego’s too big for that.

I started feeling like a painter when my image started to be more clearly constructed. What I would consider my first paintings were a series of portraits. It was much more painterly and free-handed, and they felt like actual paintings. But it's also the validation of having it in the gallery and the fact that it existed as a physical object.

CKE: You’re also interested in the dynamic between absence and presence, which is also connected to liminality. Can you describe in what way this dynamic is present in your paintings?

LG: The figure that populates the painting is often never seen directly. It’s through a window or through a reflection or some kind of a filter. So you never see the exact person. So, in this way, they’re like vessels for the viewer to inject themselves in. That’s why I try to have them as neutral as possible—for everyone to be able to imagine a narrative of their own. The absence is much stronger than if I put someone in there explicitly.

CKE: Liminal spaces are also a phenomenon online, if you think about back rooms, for example. Are you more interested in liminal spaces online or offline?

LG: That’s a great question. When you wake up in the middle of the night, it’s an interesting moment because you’re not awake but you’re also not asleep. You are in this moment of conscious and subconscious. For me, it’s the most tangible liminal space that I can see. And it’s super terrifying. It’s almost like being stuck in one thought. It’s my nemesis since forever. But it's also where some of my greatest ideas have come.

Installation view of Louisa Gagliardi, “Whereabouts”, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Vienna, 2024. Photography Jorit Aust. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / Vienna

CKE: Have you ever had sleep paralysis?

LG: Luckily never, because that sounds next level. I would never sleep again.

CKE: It very much feels like an out of body experience, as you’re conscious of being in this state and in your body but you’re unable to move and are still sort of experiencing dreams or hallucinations.

LG: I also like the moment before you wake up in the morning, just before you gain consciousness again. I always try to stay in that zone, because that’s a productive zone.

CKE: And are you also inspired by dreams that you have? Are you transferring them to your paintings?

LG: Yes, for sure, but never one to one. Sometimes I dream of painting. When I approach a new body of work, I never like to have too clear of a concept because I like the subconscious aspect. I just paint and see where it leads me. For this show, it was a little different, because I had the space in mind, and I really wanted to work with these literal liminal spaces.

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

Related Content

The American Dream Doesn’t Exist, It Never Has

The Undercurrents of Materials: CUDELICE BRAZELTON IV

Finding Romance in the Grotesque: JON RAFMAN

Jan Vorisek’s Devotion Strategy

A Martine Rose Slip: JORDAN/MARTIN HELL

Art World Resorts with Charlotte Diwan

Art World Resorts: artgenève

Image Stacks With ISABELLE GRAW

Image Spamming with Paul Hameline

Who Is an American Artist?