Harry Nuriev’s Critique of the Industry

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

Although it sounds preposterous, visual pleasure is often frowned upon in the art world. An artwork that is too documentable, too photogenic, and too ready to be posted on Instagram immediately arouses suspicions about its intent.

But “Instagramability”—an atrocious word of our social media era—which can also just be translated to visual appeal and coherence, does not automatically lead to superficiality when it comes to the object’s meaning. Slickness does not automatically result in flatness.

For artist and designer Harry Nuriev, who founded Crosby Studios—an interior architecture and design studio—visually pleasing work is something that just comes naturally to him. With a background in architecture and furniture design, he now debuted his art in a solo exhibition at Dittrich & Schlechtriem titled “The Foam Room,” which consists of a mirror installation continuously discharging foam. The foam’s air bubbles quickly vanish and the artists sees this process as a metaphor for the fashion industry’s fast pace, our fleeting attention span induced by the digital world, and fast changing marketing strategies that utilize artists as commercial tools.

The exhibition was in partnership with Dittrich & Schlechtriem and Electronic Beats. On the occasion of the exhibition opening, the gallery also hosted an afterparty, with line-up curated by Electronic Beats and featuring DJs Dixon and Fiona Zanetti.

In this conversation with Claire Koron Elat, Nuriev discusses the industry’s abuses, consumerism, and the line between art and design.

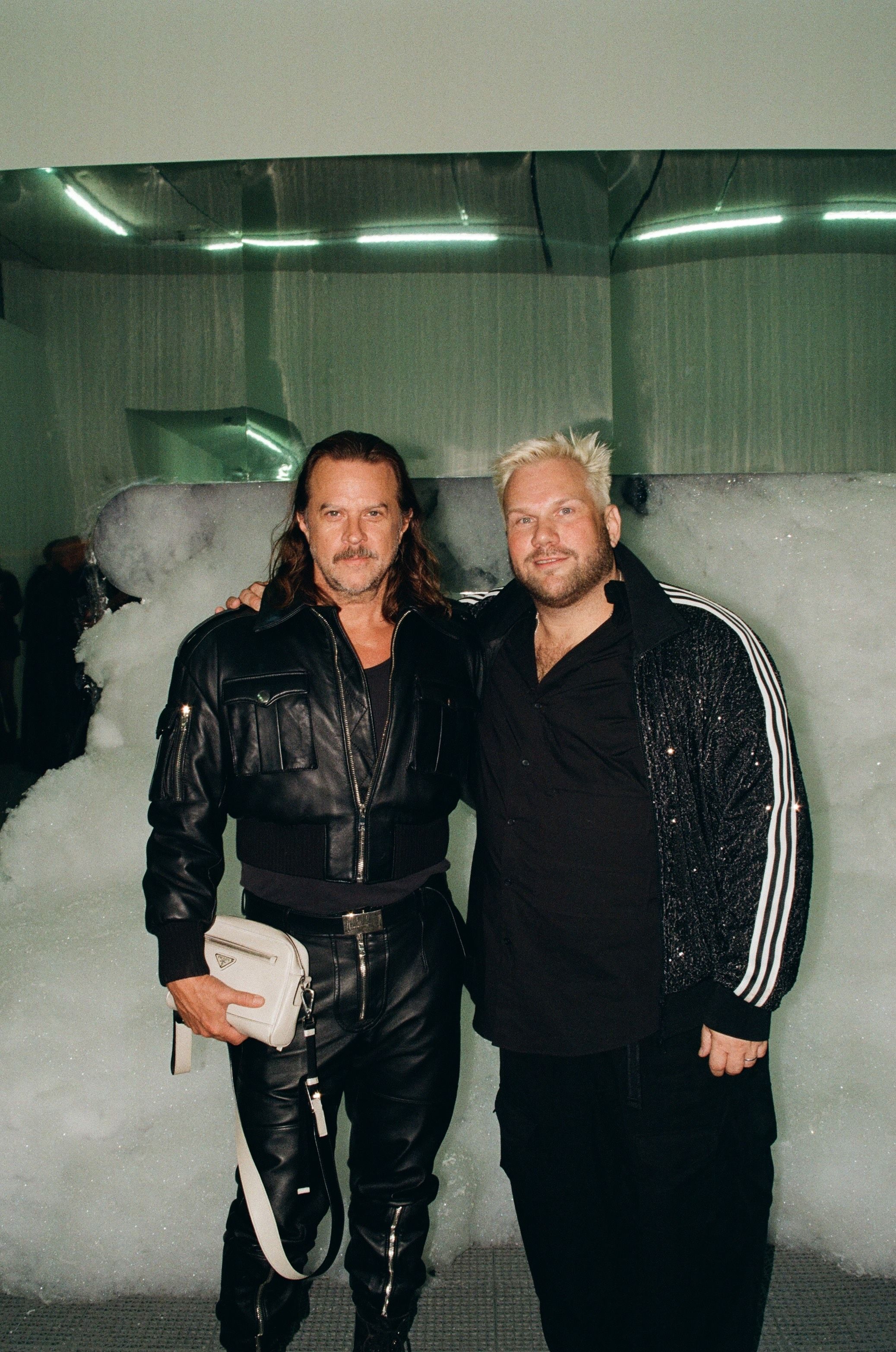

Harry Nuriev at “The Foam Room”, 2024.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: For your exhibition at Dittrich & Schlechtriem you created a colossal foam installation that generates and releases large amounts of white foam, gradually filling the gallery space. What is this construction supposed to signify?

HARRY NURIEV: The idea was to capture my feelings and thoughts about consumption. I didn’t have a clear vision of what this room or the object is going to look like. Foam perfectly mimics this industry. I’ve been to a couple foam parties and always thought they’re an interesting environment—kind of like a reunion. A space where people feel more comfortable in their skin and have more access to their feelings and get the ability to share that with strangers.

With all your insecurities, questions, and confusions, you sometimes have this black hole in your soul and you’re trying to fill it with something. The foam also acts as a symbol for marketing and things that you consume but don’t actually need. It takes up your space and provides you with a lot of things, and then eventually it disappears.

Exhibition view, Harry Nuriev, “The Foam Room”, 2024, courtesy of DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM.

CKE: Would you describe this object as a form of critique? I’m thinking about this especially in the context of you also working in fashion industry where everyone seems to be aware of over consumption but still participates in it.

HN: Yes, it is a form of critique. For the last five years I felt really abused by the industry—not just fashion but overall. I miss the time when artists were not introduced to industries. Now we dress to fit the persona we have to communicate and have conversations about things that didn’t used to be important but now entirely take over spaces. And I feel like I’m also responsible for this in some ways. So, now that I’m focusing more on my art practice and have a platform, I feel the responsibility to address certain issues.

CKE: In what ways do you feel like you were part of the problem? And when did you realize that you want to change?

HN: It was when I decided to focus more on art. In my work, I talk a lot about transformism and the idea of repurposing things. We don’t live in an ideal world, and consumerism is not ready for this conversation. But I just felt like I needed to do something, even if this is just the first step. I’m happy that I started now because I postponed it way too long.

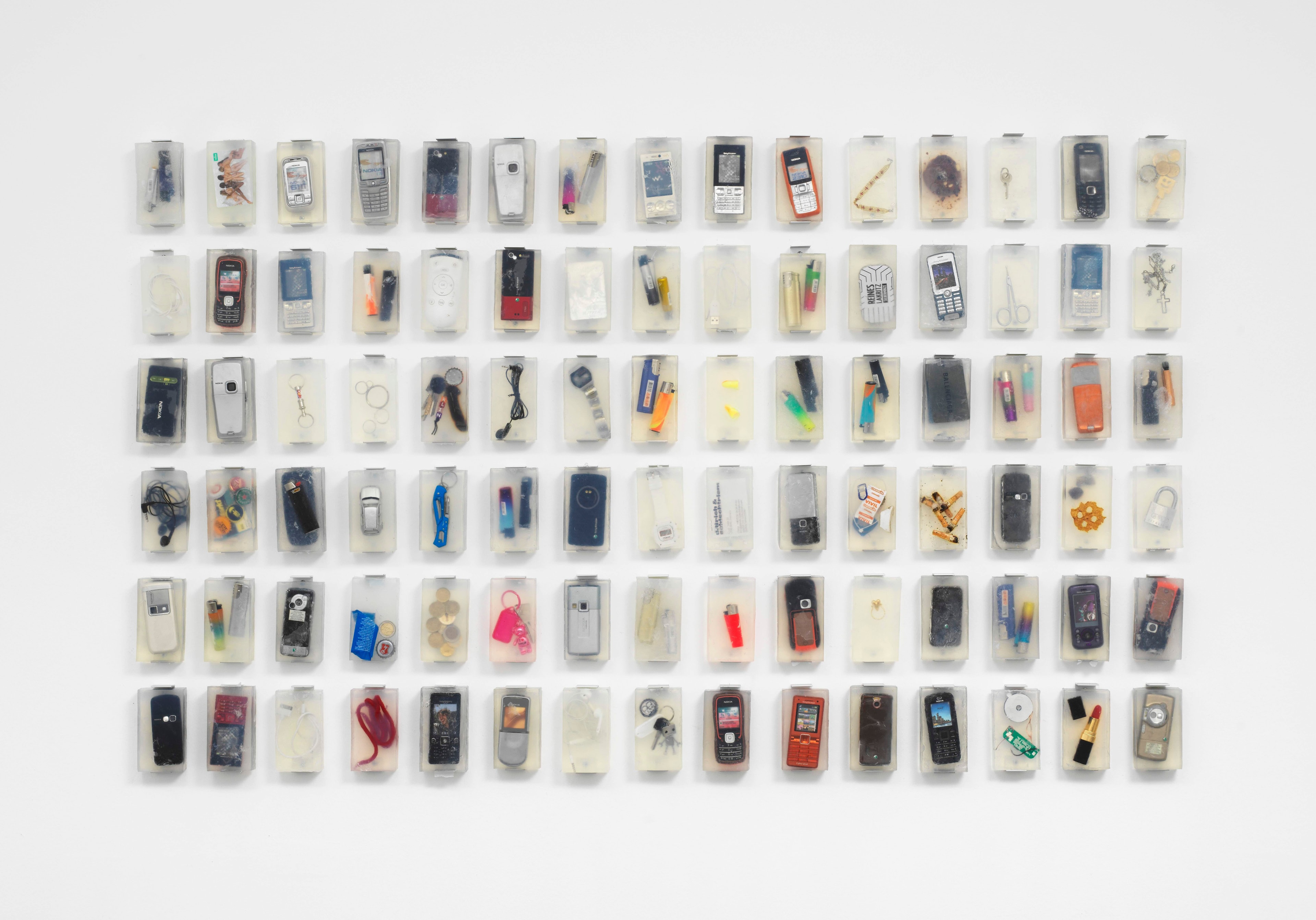

Exhibition view, Harry Nuriev, “The Foam Room”, 2024, courtesy of DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM.

CKE: You’re showing this work at a gallery, but you also have a design background. Would you define it as an artwork or a design object; where would you generally draw the line between art and design?

HN: That is an interesting and quite sensitive question for me. After art school, I was pushed to have a real job. So, I went to university and studied architecture. It just happened that my life started heading in a professional direction. Most importantly, I didn’t really have time to analyze the specific direction. When I first started out, I thought that my work was more situated in art, but I just put an extra layer of function on it to make it live in a different territory. I was used to providing a service, and people liked it a lot, and it became quite popular and successful. At some point, I got sick of doing art that is functional, so I decided to work in this new territory. I’m not doing this because it’s fancy or trendy, it’s because I really have to say something—and I can’t express this in different institutions. They limit my alphabet, and function is killing the conversation because it’s just fully absorbing…

Exhibition view, Harry Nuriev, “The Foam Room”, 2024, courtesy of DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM.

CKE: There are a lot of people in the fashion industry who go through this shift. After they’ve produced a lot of commercial work, they then focus more on creating art. Would you say that you’ve always created work that needs these different spaces to exist in? And when you worked with commercial clients or brands, would you say that this was very limiting for you?

HN: I was very lucky to not be limited by people who walk into my life and commission work. I want to point out that I don’t really define my work within certain categories. It’s not a part of me; it’s an extension of me. It’s not something that I just produce, broadcast, or tell a story. It’s actually me. I was just at a point where I felt displaced and confused. People liked my work, but I wasn’t satisfied because I was always in the wrong room.

CKE: I read a couple articles that claim that you design spaces for the Instagram age, which sounds a bit stereotypical. Would you agree with this?

HN: I hated this quote, because I think it immediately downsizes your practice. I understand that people really want to document my work. It’s a way of keeping it, taking it home, and owning it in some way. So, a photo is the easiest way to do that. This article came out around 2017 and was the moment before people got offended when you don’t post their stuff. Now, if you don’t post it, they think you didn’t like it. Today that’s our way of communicating, which is kind of fucked up.

Exhibition view, Harry Nuriev, “The Foam Room”, 2024, courtesy of DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM.

CKE: I think this aspect of “Instagramability” also relates to the idea that creatives purposefully make visually appealing work that can be captured with a camera. To some extent, even art making is more about imagemaking and creating recognizable visuals that have the potentiality to go viral in a digital space. And this approach might be quite frowned upon in the art world but it is totally normal in the fashion industry as well as in advertising and marketing.

HN: I think in art, the creative process can have many different meanings, it can contain a lot of pain and fear, and a very dark side of human beings. I would say that art doesn’t serve aesthetics. It serves our soul, and this connection is invisible. So, it doesn’t necessarily have to be super pretty or clean. I personally love proportions, and I’m really good at it, so everything I do has an aesthetically pleasing side to it. I’m not against that visual side of the work as long as the work induces a strong feeling.

CKE: It’s interesting how you talk about the visually pleasing side of a work. Thinking about fashion photography, for example, a lot of it is straight forward beautiful, and it’s very much taking aesthetic pleasure as a priority. At the same time, you also have photographers and brands that work towards the opposite direction, where ugliness becomes the new prettiness.

HN: I think we are obliged in some ways to keep certain visual standards. It can be quite stressful to keep up these standards because let’s say, you have ten points in the beginning and use up eight points to focus on the visual side—so then you’re left with two points to put meaning into the work. That’s against real art for me—against the idea of evolution in general because it’s going from internal to external. I’ve worked with many different fashion photographers and all kinds of talented artists, and I have to say that a real, talented photographer does not really care about the final visual aesthetic. They really try to catch the moment. They are not taking a photo of the person, they are taking a photo of the soul behind the body—and you can feel it. And surprisingly, it’s always beautiful.

“The Foam Room” afterparty, hosted by Electronic Beats and DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM, 2024.

Courtesy of Electronic Beats and DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM.

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

Related Content

“Bones and Wheels” by Daniel Hölzl

Productive Narcissism

MAKE LOVE IN MY ROOM: Harry Nuriev’s Eastern Interiors

Maggie Dunlap’s Teenage Murders

Strange Bedfellow: An Ode to the Outsider with SOUFIANE ABABRI

Tor Studio Evades Synthetic Claustrophobia

Adulting with ANDREJ DÚBRAVSKÝ

Reinventing Mike Kelley

032c Gallery opens in Seoul

DEAR MICHEL MAJERUS (1967–2002)

032c Launches Mike Kelley Special Capsule Collection

Exclusionary Design: You Can’t Sit Down in Modern Cities