“Don't be gay”: HUGO BAUSCH BELBACHIR Courts Bravery and Revenge

|Henry Levinson

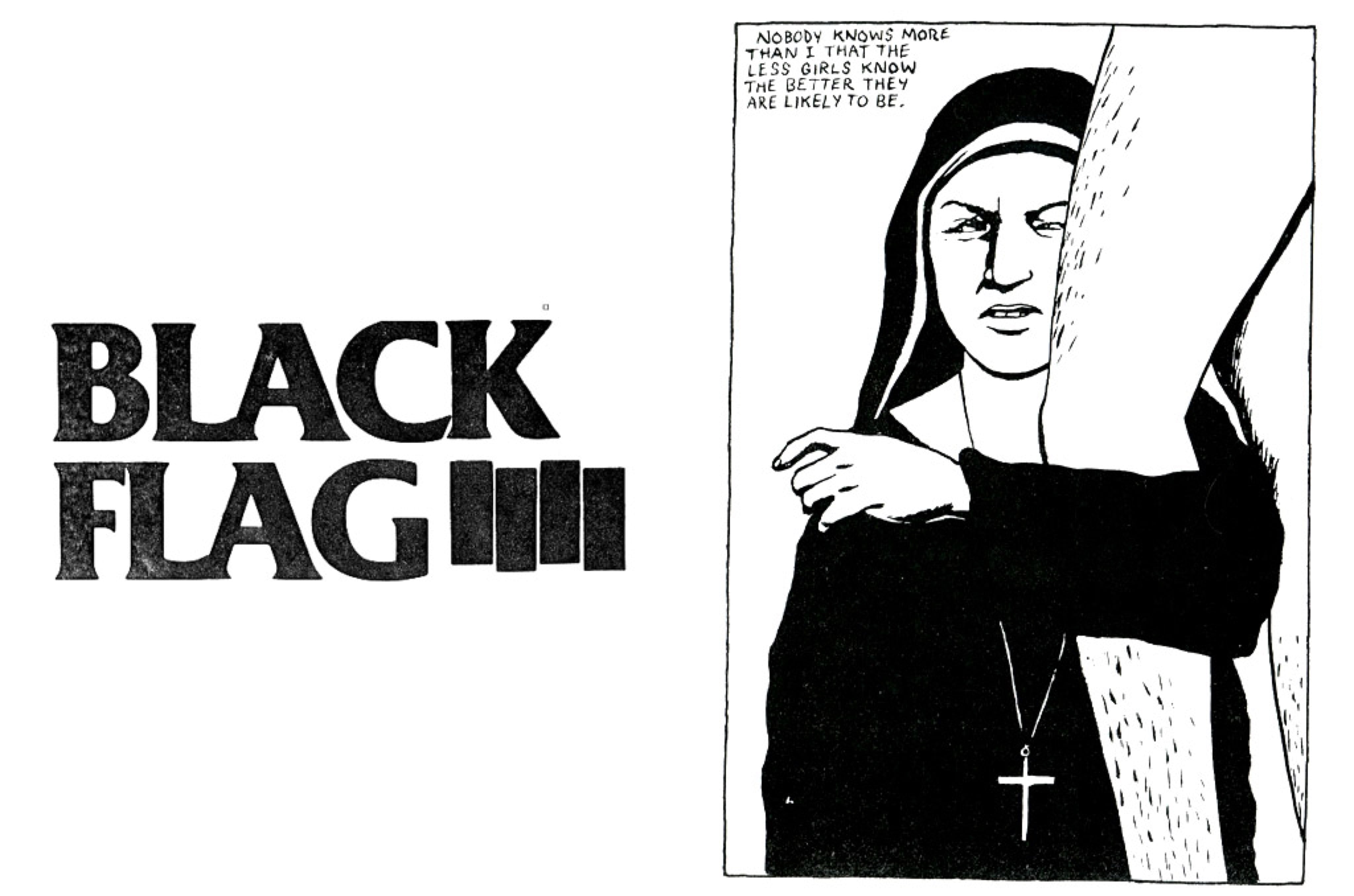

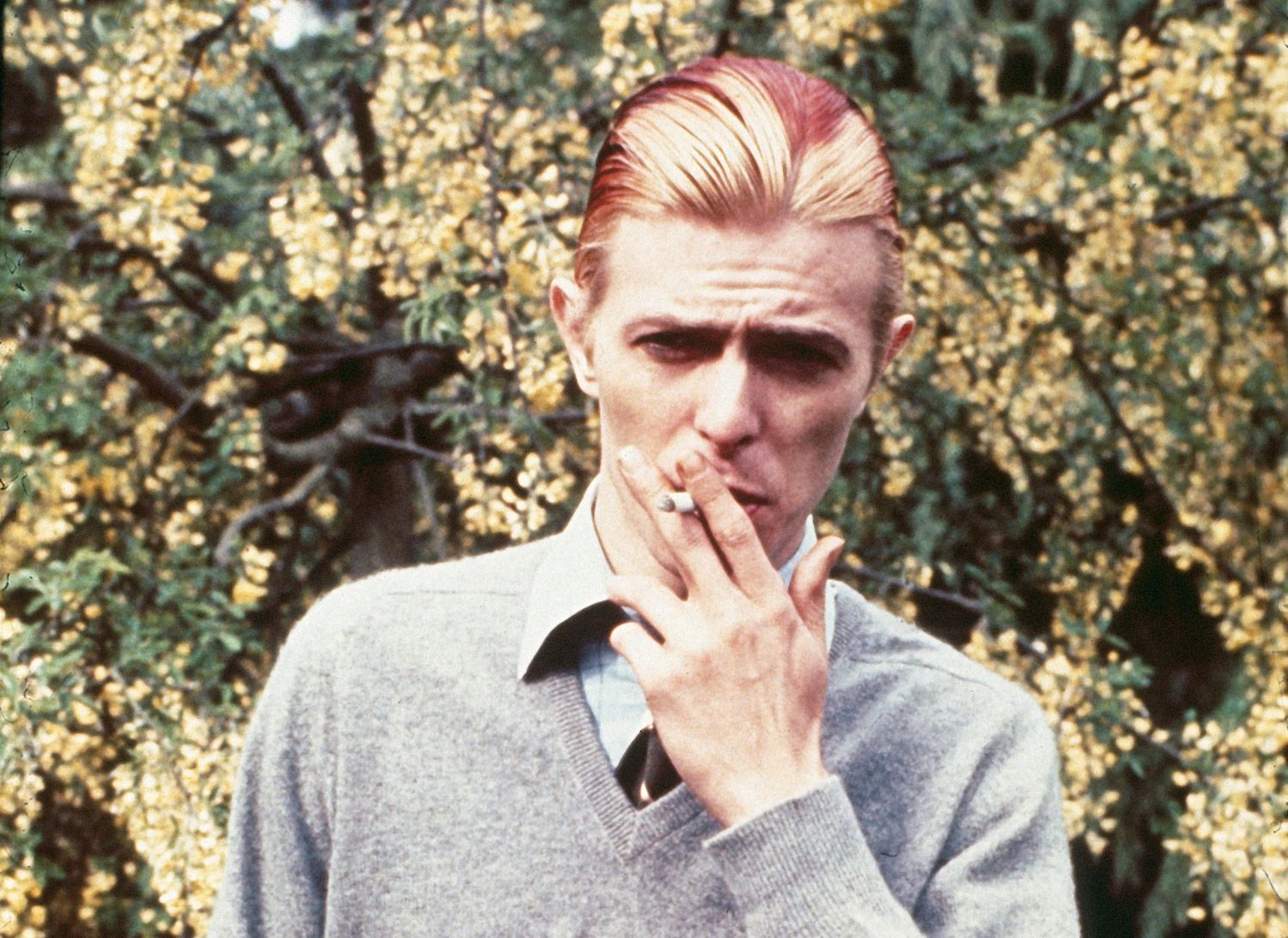

Bruce LeBruce got punched in the face walking down the streets of Toronto back in the 1980s. His attacker: a broad shouldered Englishman sporting a mohawk. In the subsequent years after the incident, LeBruce, alongside fellow members of the so-called Sissycore scene, had co-founded the fanzine Juvenile Delinquents — J.D.s — alongside collaborator GB Jones. J.D.s' heavy involvement from the artists, sex workers, authors close to the punk scene at the time were critical to a proud reclamation of the punk aesthetics and politics.

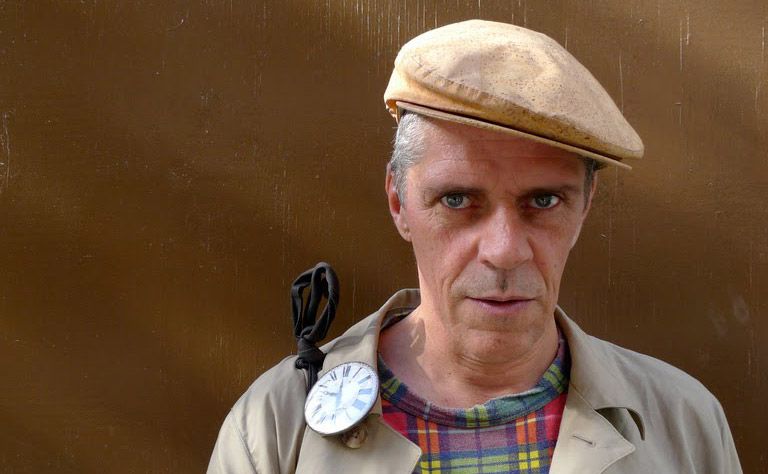

HENRY LEVINSON: What is the starting point for this exhibition?

HUGO BAUSCH BELBACHIR: The starting point is somehow personal; it's me in my bedroom, as a teenager, displaying some facsimiles of this J.D.s’ fanzine that I had found at the time on Internet Archive. I remember this period as an important, almost frontier moment, and one that made sense with the stories I read in J.D.s. The idea for this exhibition began when I returned to this memory. When Bruce LaBruce and G.B. Jones decided to co-produce a fanzine in the mid-1980s, they were only a few years older than this teenage me. They had both just met at York University in Toronto, where they studied film. At that time I was taking my first BA, and I had a feeling of admiration for both of them. To go back to that, as a research project, was to reconstruct that history in the manner of an autofiction. As a curator it is a very important form for me, to get close to a writing impulse.

HL: Looking at the fanzine, the character of a gay skinhead comes across most often.

HBB: This is a relatively central figure in the punk movement, and an interesting one insofar as it contradicts its original intention. The exhibition focuses on the epistemological work of Bruce LaBruce and G.B. Jones on the queer foundations of the punk movement. "Punk" takes in fact its etymological roots in the same places as "Faggot," which referred to a piece of flammable wood, a stick. The figure of the skinhead, that silhouette of a straight white male with a shaved head and violent political attitudes, places its ambivalence in a relationship of seduction and repulsion, and as a concept. Quite simply in the 1980s it was impossible for female-identifying, gay, and trans people to establish themselves in radical punk scenes as they were run by straight, skinhead groups. There is something related to perverting symbolic figures, in what they evoke of a sense of fear, exclusion, and then excitement or fantasy.

HL: In gay porn and erotica, there is quite a focus on the punk look or archetype; the shaved head, the jock body, the tough attitude. What do you understand as the connection between these forms of erotica and the punk archetype or cultural aesthetic in general? Why do you think there is such a strong relationship between these two things?

HBB: Maybe it has to do with this idea, again, of perverting figures of authority as a mechanism for overturning a system of domination. Just like the importance of the Nazi aesthetic in Fassbinder's films, without ever reactivating its ideologies. And then in all its excitement and confusion. Everything that Sontag expressed with Notes on Camp.

HL: There’s a sort of fascination with and a renaissance of the punk look today. You'd talked about the political significance of queer punks who previously were often in opposition to the hegemony many straight people felt they had over this punk identity, and the push-back on their perceived ownership of punk. Do you think this contemporary revival has the same ethos of fighting against something as in the past, or if the current form a purely aesthetic exercise?

HBB: I don't know. It is also part of our contemporary behaviors that tend to appropriate every aesthetic by denying its political relevance; there are too many things for one and the same thing to stand out, and everything becomes the same. Maybe that's where it comes from. But I don't know. To be honest I don't really have an opinion on it.

HL: There is a very noticeable anti-Nazi motif within the fanzines. What’s changed between the engagement with queer identity, Nazism, and the fight against Nazism between when the zine was published and now? It seems like today, there are so many more visibly, openly gay and queer people who are blatant, vocal fascists. What, through your research, have you learnt from the past and compared to the current moment with the queer and gay community and their engagement with Nazism?

HBB: Creating a scene within a scene is also about questioning one's own boundaries. The punk scene at the time was predominantly white, while the movement itself had been started by black bands and figures - Little Richard, Death, Pure Hell - and was distinguished by its fascist, misogynist and homophobic structures. I think all this was also political work, and that's what stands out most in this exhibition. The whole point of Bruce, G.B., and their crew was to create a safe space.

As for the fascist symbolism in the fanzine, I think of it more as a tactic of ironic appropriation, as we talked about earlier. A kind of deconstruction of the aesthetic scheme as revenge. I've always found it very important to keep these symbols - beyond those of fascism and Nazism in particular - as a responsibility of history, from which it is possible to form counter-attacks. I have just returned from Berlin, which is still strongly marked by its despotic, terrible history, that of the Second World War and the separation of the city during the decades of the Cold War. A lot of things are still there, witnessing, and the inhabitants are organizing themselves to establish a new life - I find that very important. As for gay fascists, I don't know, I don’t ask myself too many questions about them.

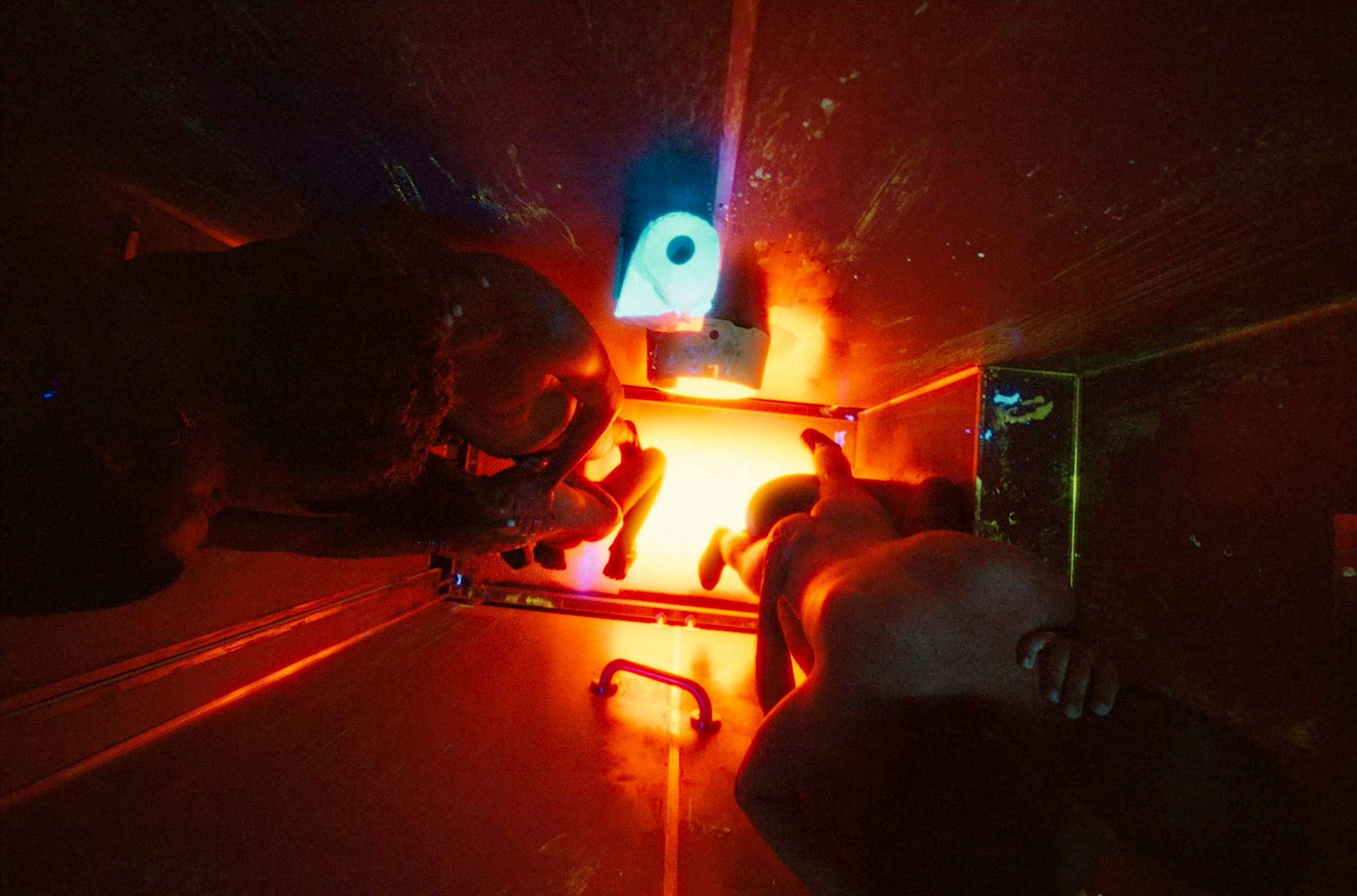

HL: In Berlin and Germany as a whole, the modern gay/queer scene is in many ways intrinsically tied to the remnants of Nazism. Of course, this manifests in ideological ways, as there is shamefully a lot of overlap between the fascists, racists, and the far-right with gay and queer people — the leader of Alternative für Deutschland, Alice Weidel, is herself a lesbian. But it also manifests this legacy in a physical way too. For example, the building the Boros Collection is in now was originally built by the Nazis as a bunker for air raids and later in life was a massive fetish club.

HBB: J.D.s was also establishing this situation; going into a place that is hostile to you, a place that is a space of potential danger, of threat. Something to do with daring, bravery and fear too. It's also beautiful to think of these places as spaces that we have reappropriated and whose historical charge takes on new importance since it is in our hands.

HL: Do you think that this idea of bravery underpins the connection between sexuality, power, and violence?

HBB: Yes, the exhibition has a lot to do with the concept of revenge.

HL: It's interesting that you say “revenge” in response to the word “bravery.” Do you think there is a relationship between bravery and revenge?

HBB: Always. Don't you think?

HL: My inclination is toward reconciliation as an alternative.

HBB: I am relatively opposed to the idea of reconciliation.

HL: In the context of politics, I am against that idea of revenge. But in a queer context, the idea of revenge might be framed differently. I think many gay and queer people see themselves in relation to the person they were before being out. Achievements in their new, open life are perhaps some sort of revenge against the people who made them miserable in the past. That is an empowering form of revenge maybe, so perhaps revenge can be both good and bad.

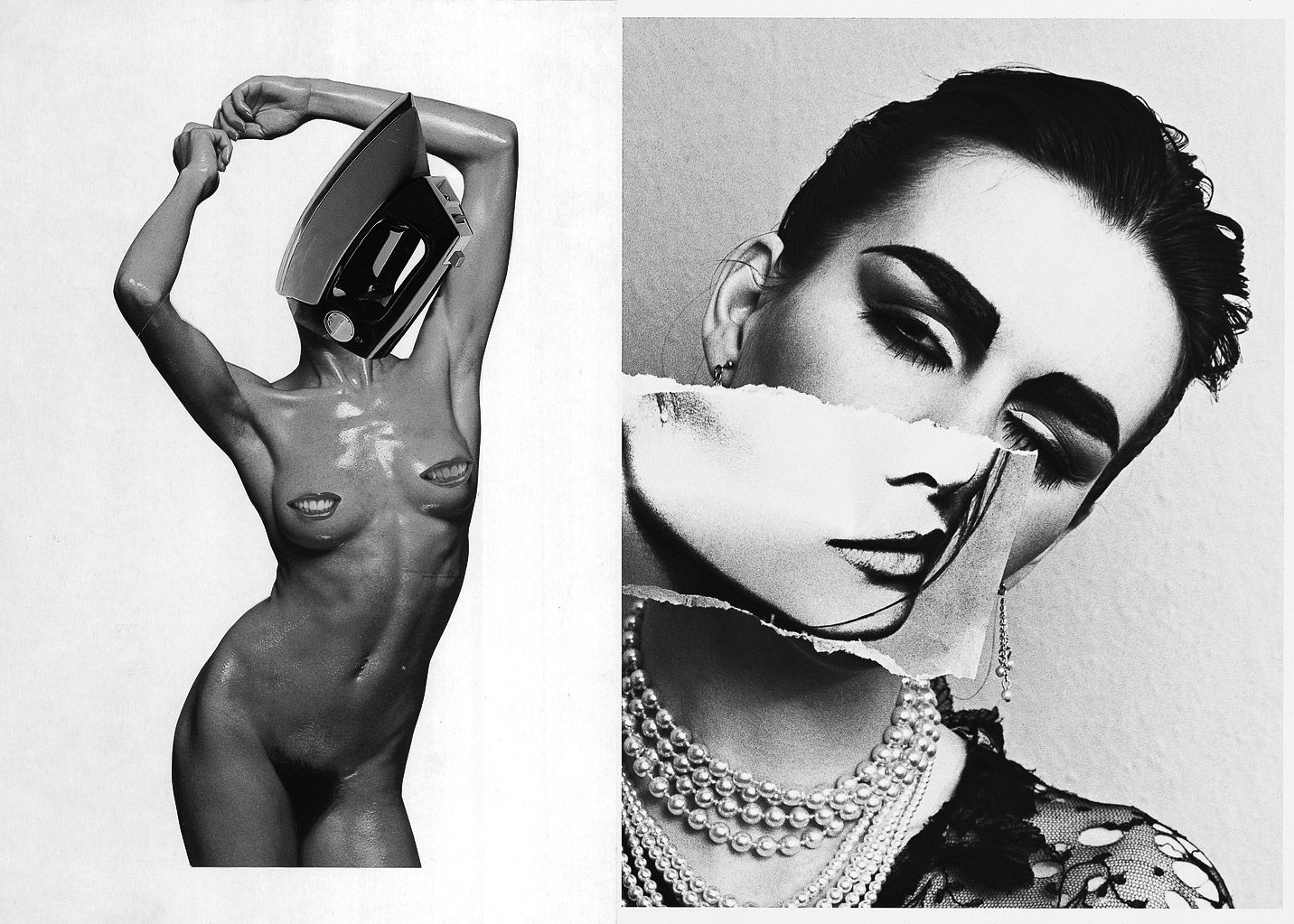

HBB: J.D.s tended more to establish a set of radical narratives than to form an actual militia, although they did call themselves 'The New Lavenders' in reference to the San Francisco queer armed group, itself inspired by the Black Panthers. I think that in the context in which we are, which is structured by economic and racist politics, to agree on reconciliation is to deny the ongoing violence that is being exerted on different our bodies. J.D.s did not call for arms, on the contrary, but for poetic revolution, for the removal of power through fear and seduction.

HL: It takes bravery to be able to (re)assert oneself into a space that was taken from them in the first place.

HL: The zine seems steeped in nostalgia. Why do you think there's a nostalgia to this era specifically?

HBB: Nostalgia is an important concept, so much so that the exhibition - or rather this research work - is opposed to it. To think of various struggles through the prism of nostalgia is to attach it to a past of struggle that is admirable - in fact, it is - but at the same time to assert - by implying this concept of nostalgia - that it is no longer possible, that it is frozen elsewhere. I have the feeling that this nostalgia tends to suggest that the means we have today, which are more massive, heavier, and more insidious, do not actually exist, or that they are not sufficient, that they cannot take us any further. But they do. And then it was very important for me, as the curator of this project, to present J.D.s as a piece of an ongoing history, to say that a continuation is underway, that the struggle continues, in different forms, with new actors. Doing this project at Giselle's book, which, in the middle of Marseille, is a space that places the importance of archives at the center of its research and presentation work. It's also a way of keeping J.D.s alive, as Bruce told me.

To think of a fanzine is to think of a reduced, fragile, poor object. At the time, no fanzine was made to last. There is of course the question of the archive, and of the queer archive, which was mainly at stake in this project, but which wanted to free itself from its nostalgic capacities. It's a project about dreaming, and what is possible from them, afterward.

Hugo Bausch Belbachir, an independent curator based in Paris, is curatorially involved at Fitzpatrick Gallery, where he directs a programme of exhibitions around the issue of the moving image. Don’t be gay: J.D.s (1985-1991) is on view at Giselle’s Books in Marseille until February 14th.

Credits

- Text: Henry Levinson

Related Content

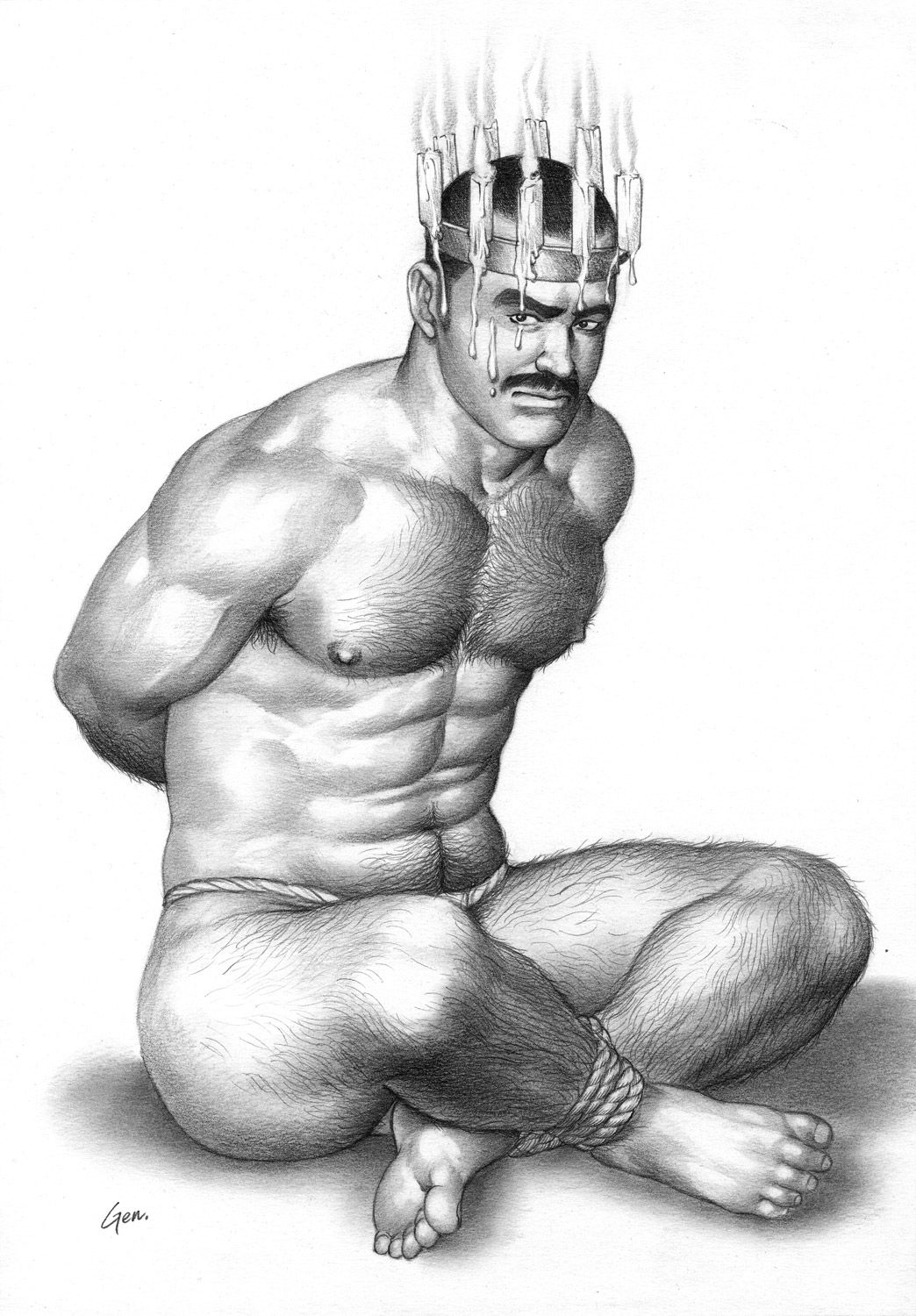

Japan’s Master of Gay BDSM Manga GENGOROH TAGAME Opens Up to 032c

The World’s Biggest Gay Social Network Now Is a Publishing House, Too!

ON MESSAGE: MATT LAMBERT and ERIKA LUST

Mining a Counter-History from the Past: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS and Subcultures in Kansas

Surprisingly slick art direction from the chaotic world of hardcore punk

“Punk Metal, Babes”: ENRIQUE AGUDO Explores Identity, Sexuality, and Mythology in VR for a Digitized Tribeca Film Festival

032c Peroxide Collection Love Story

Bad Principle Created Chaos, Darkness, and Woman

Fuck Morrissey, Here’s Linder

The Man Who Came From Hell

Jeweler JUDY BLAME and Punk’s Baroque Period