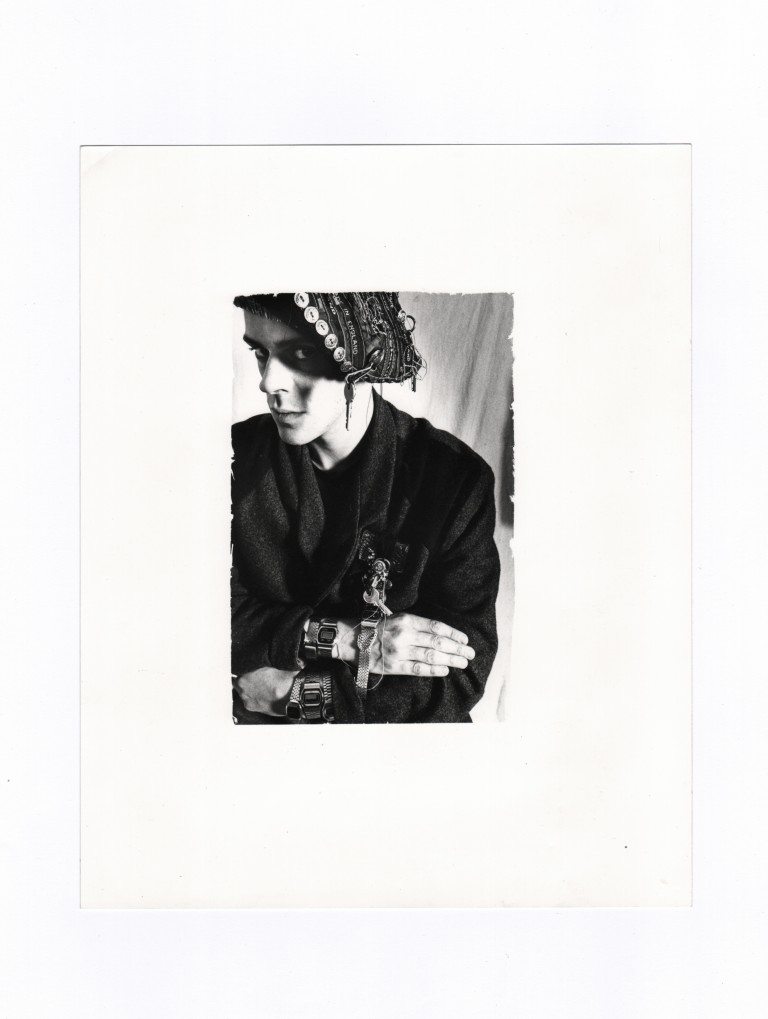

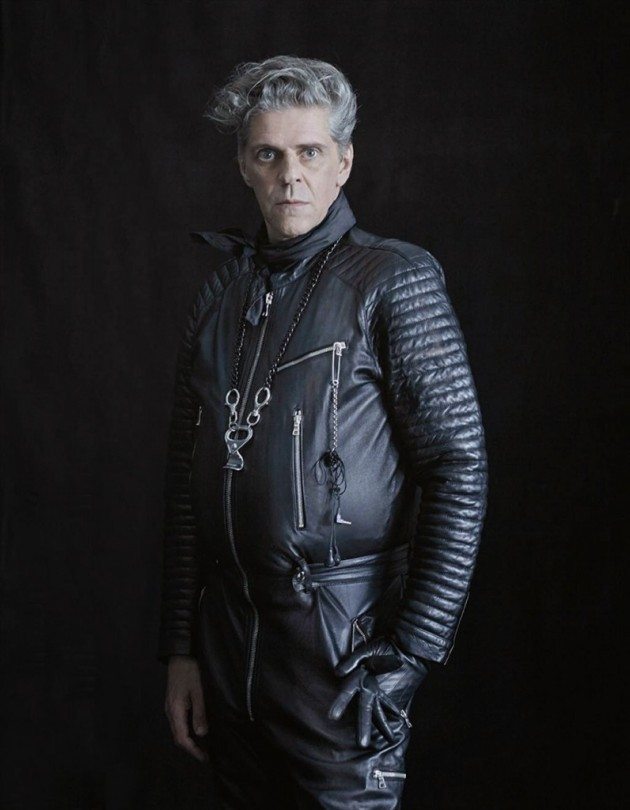

Jeweler JUDY BLAME and Punk’s Baroque Period

|MARK HOOPER

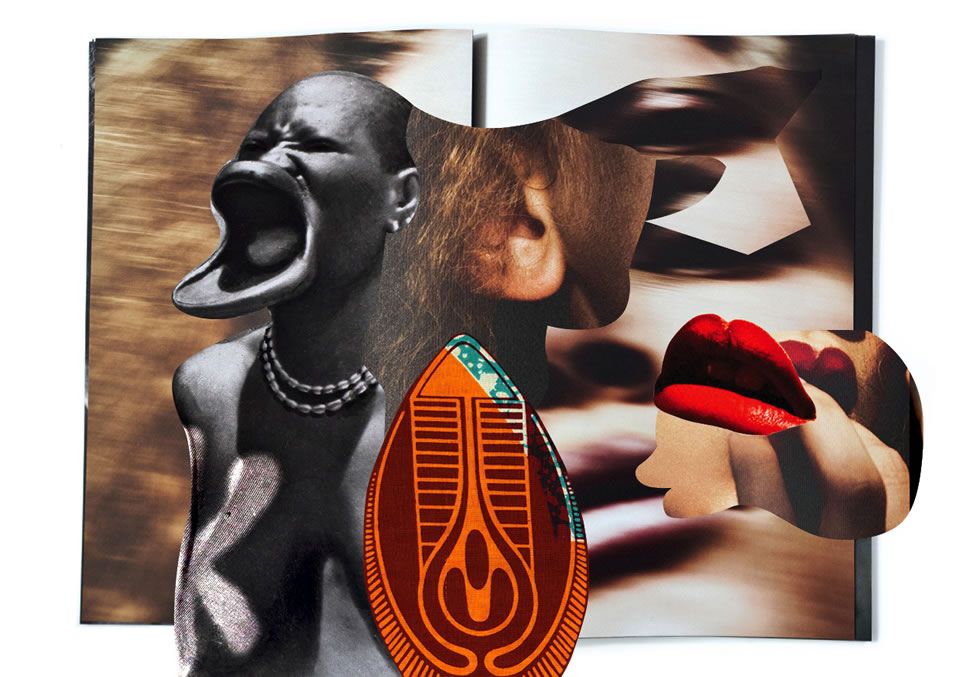

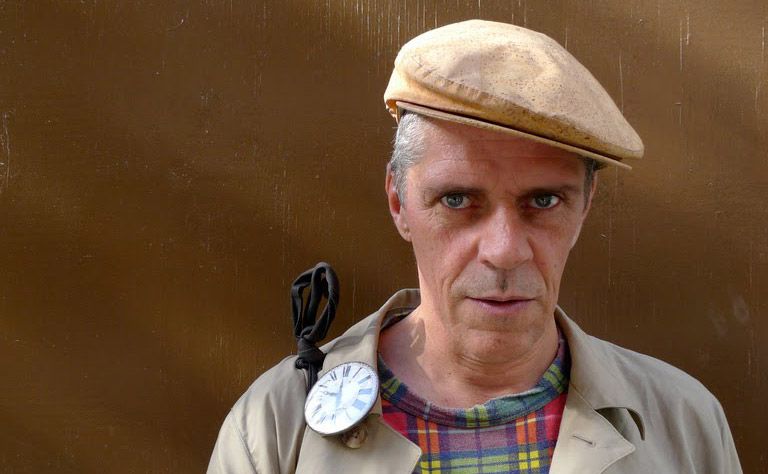

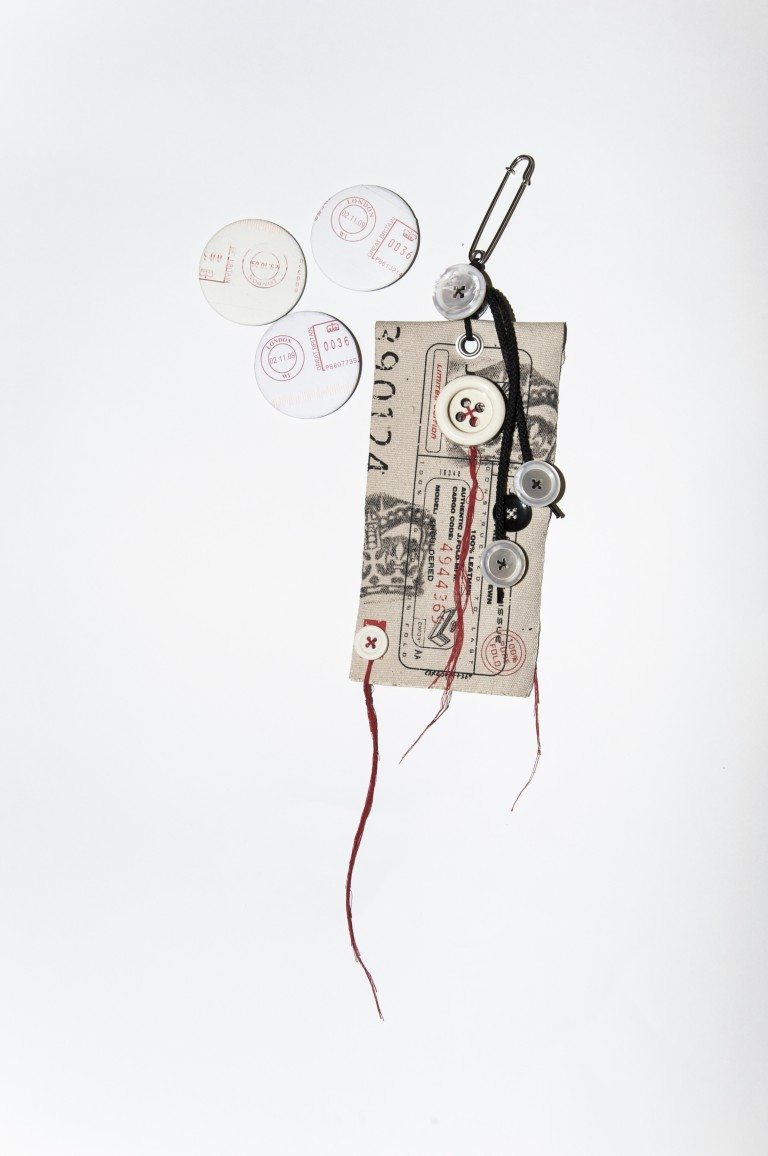

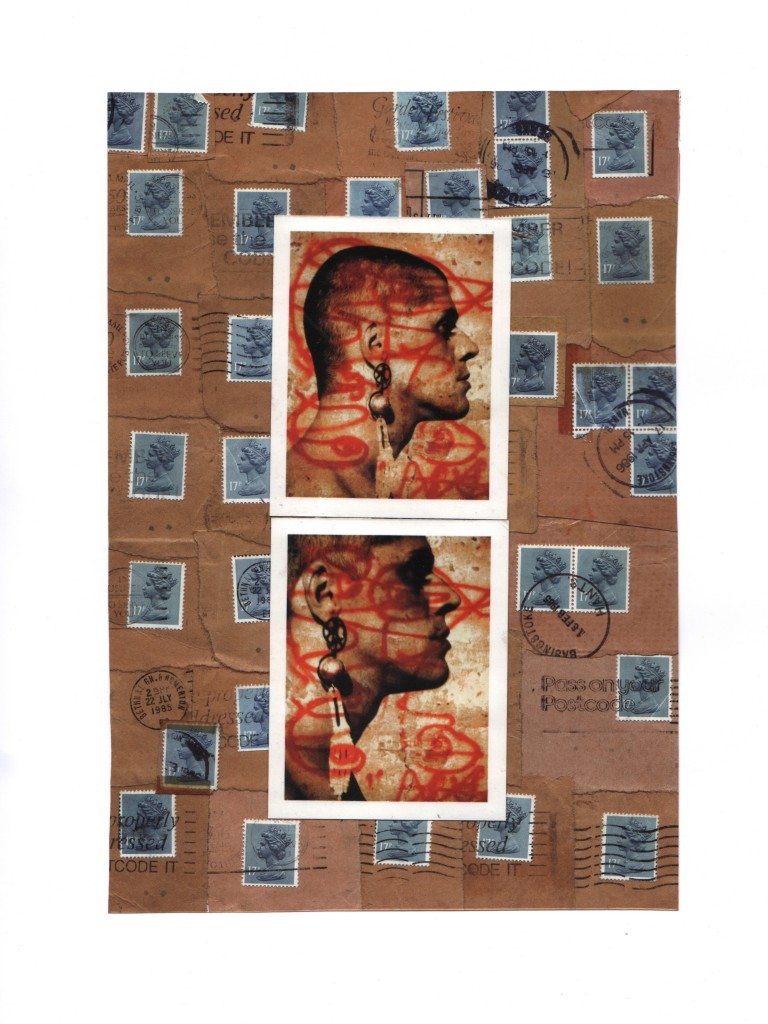

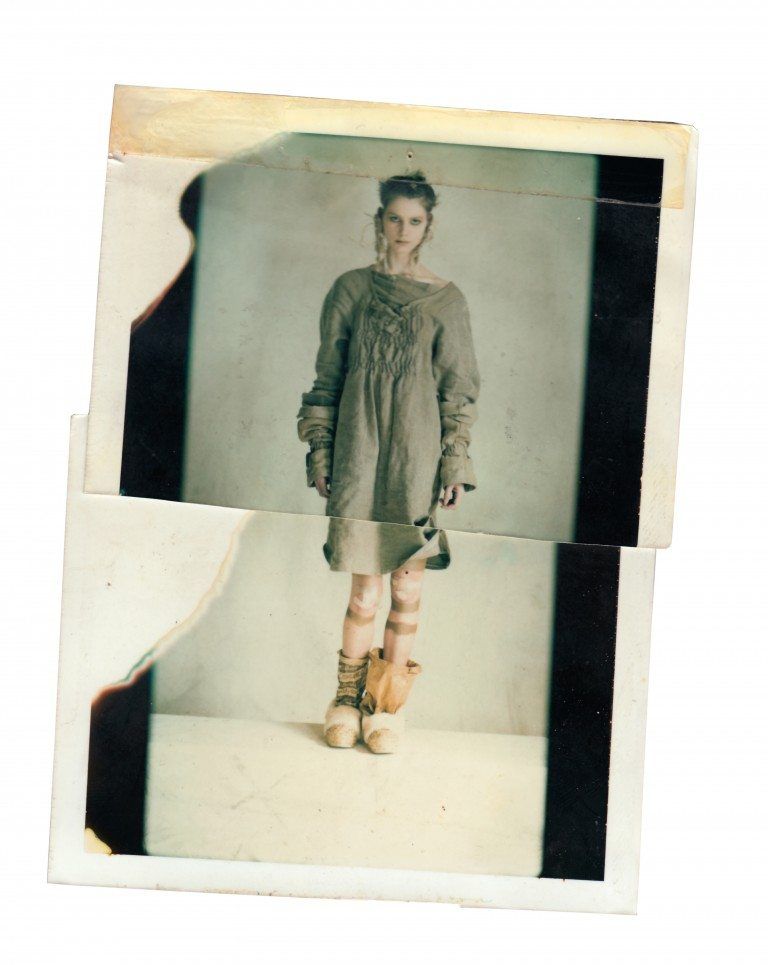

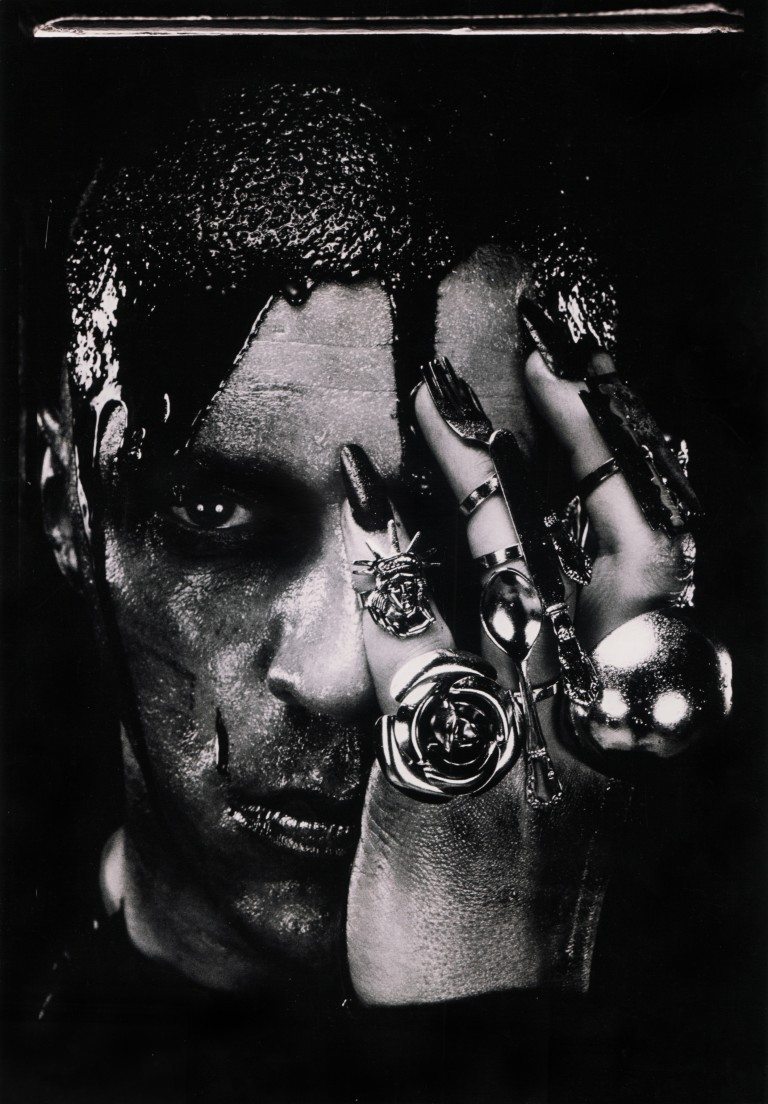

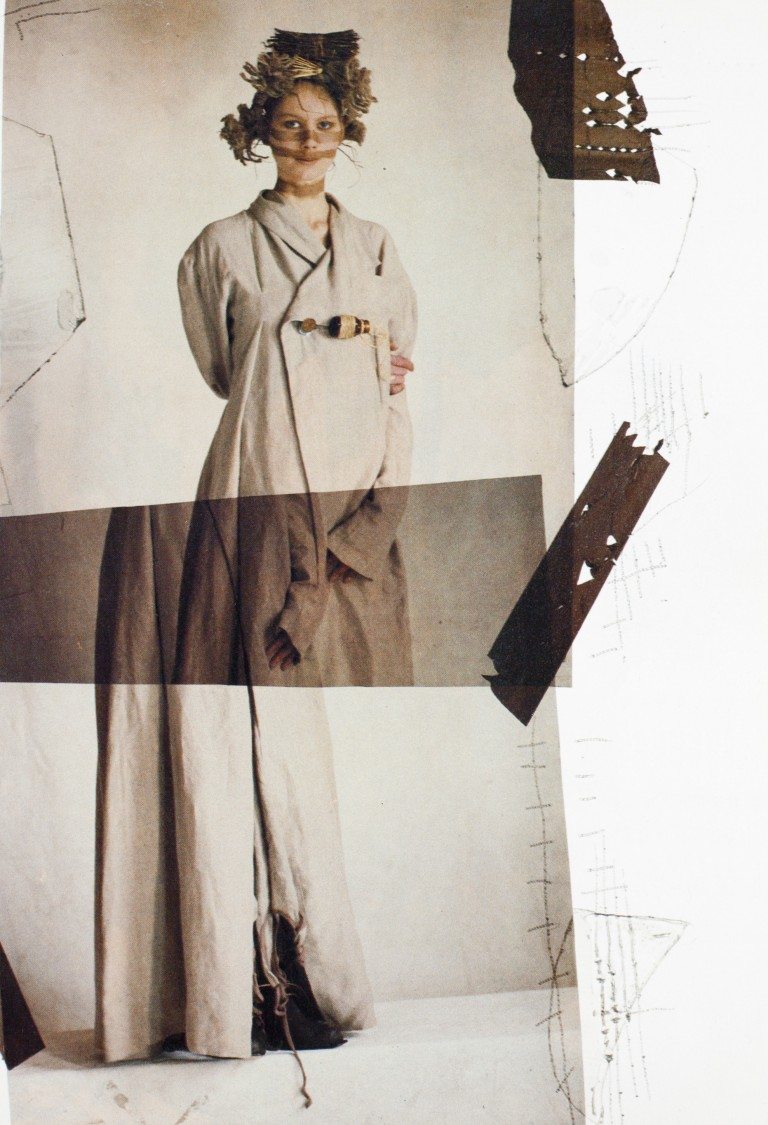

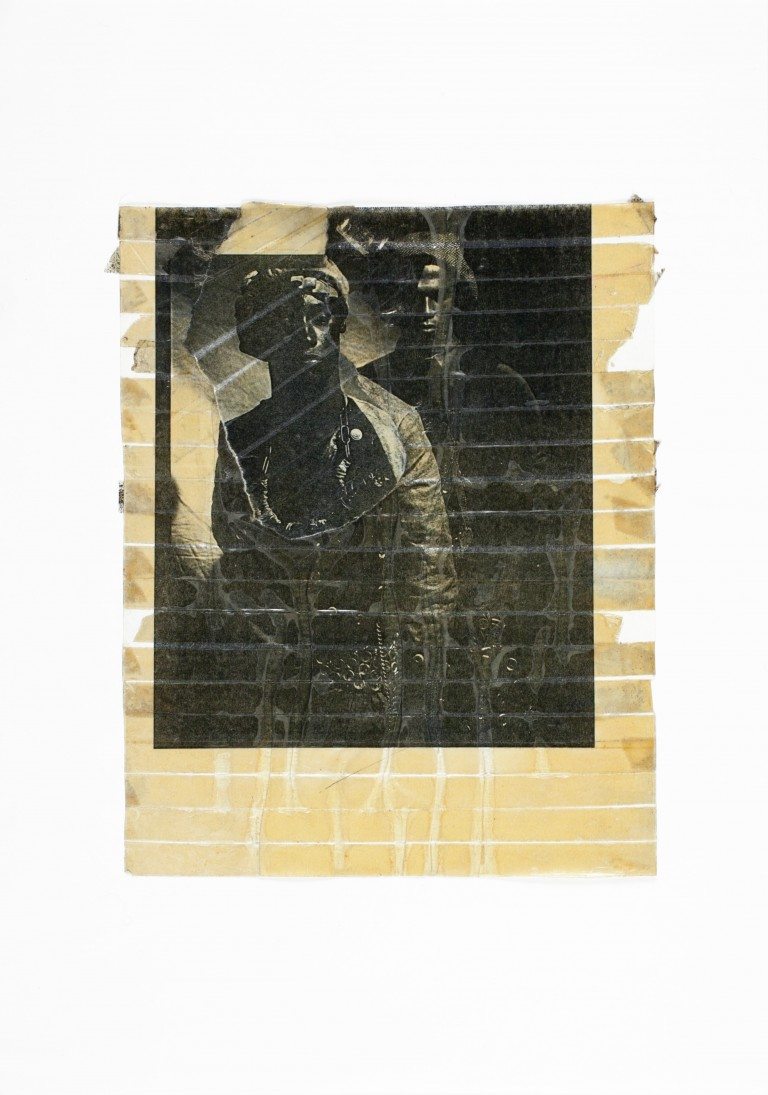

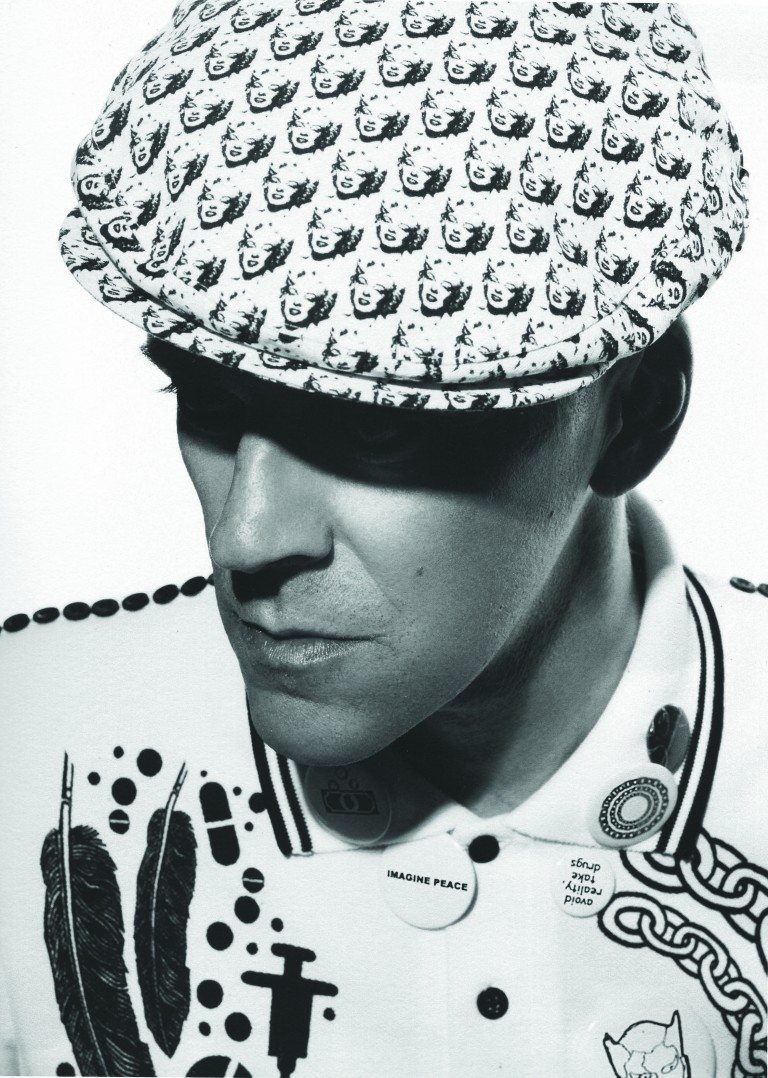

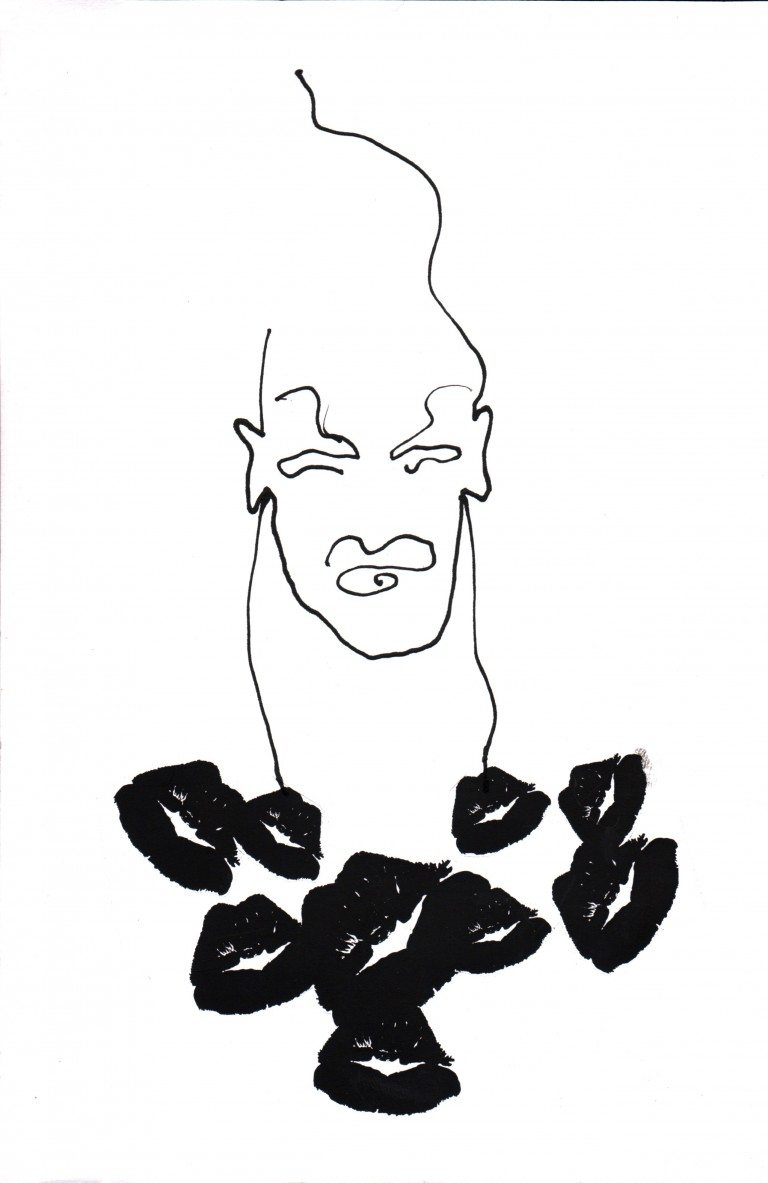

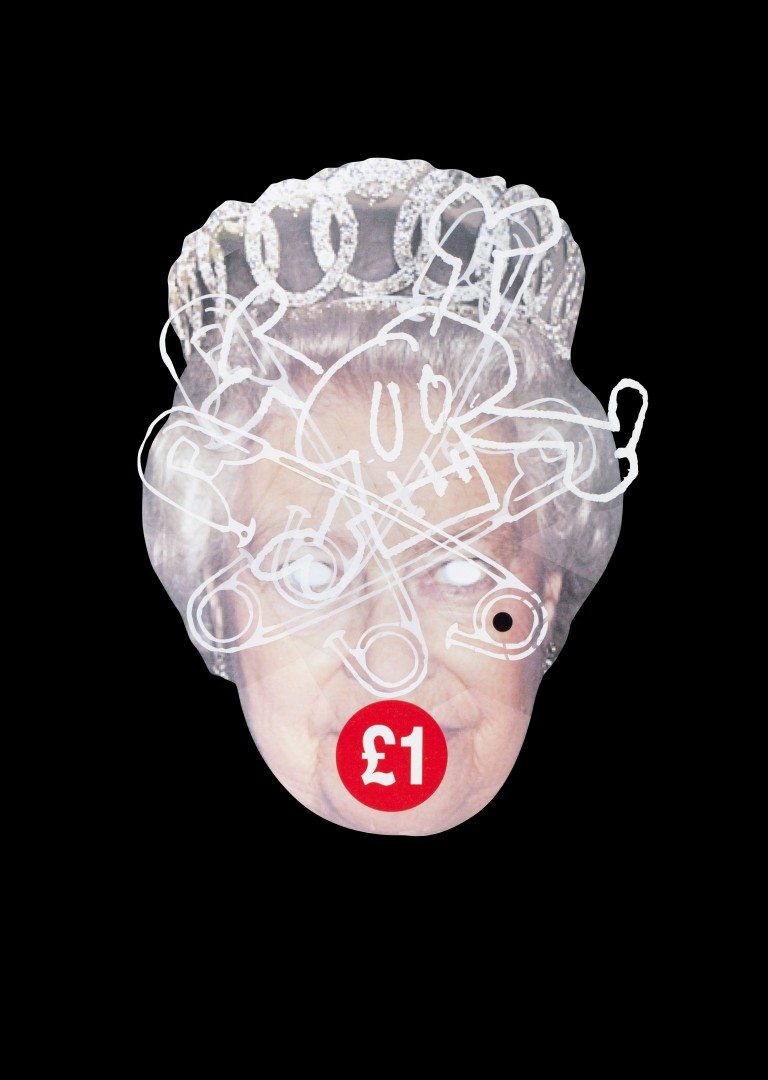

Jeweler, and stylist, Judy Blame was at the center of the British underground since the days of safety pins and Malcolm McLaren stalking the streets. He collaborated with interlocutors spanning from Rei Kawakubo at Comme des Garçons to Kim Jones at Louis Vuitton. Jammed with keys, buttons, safety pins, and sepia photos, his work arrives to us as a message from Punk’ s baroque period, entwining tropes of youth subculture and found objects into fashion shoots, collages, and accessories. We commemorate Judy Blame, who passed away this February, 2018, at age 58, with Mark Hooper’s portrait of Blame from 032c Issue #6.

“ME AND THE GENERAL PUBLIC HAVE ALWAYS HAD QUITE A DODGY RELATIONSHIP”

It strikes me that you’ve seen – if not overseen – some of the major style movements of the last 25 years or so. How did you first get involved in the style scene?

Well, if you’re talking about attitude, I ran away from home when I was 17. This was ’77. I didn’t know what running away entailed. It started with the music and the visuals of punk rock. I just saw people with pink hair playing in mad bands and just went for it. At the time I was living in Devon, in the countryside, in a tiny little village, and I just knew something else was going on. I wasn’t really happy at college so I left. My parents were quite formal, my older brother’s in the army, the other one became a policeman, my sister’s a nurse. And I’d always been really creative; drawing, interested in clothes, films, music … And my parents just didn’t believe you could make a career out of being creative, because they didn’t know anyone who had, so I was under a lot of pressure to find a career because all my other brothers and sisters were conforming. So I saved up some money without them knowing, packed my bags, dyed my hair and … I did run away to London, thinking, oh yeah, punk’s happening, I’ll just walk down the street and meet lots of people. But London was quite fashiony – Malcolm (Mclaren) and Vivienne (Westwood) ruled the roost in London, and the Bromley contingent and all that – it was a bit more snobby. I only stayed for a couple of weeks. And the only other place where I knew anyone – because I was definitely not going home – was Manchester. So I went there. And Manchester had a brilliant punk scene. There were a lot of bands, a lot of graphic people, a lot of creative people experimenting. We couldn’t really afford the Seditionaries clothes or whatever, so we would do the jumble sale, buy a suit, throw a bucket of paint over it, cut it up, join it back together with safety pins – it was much more homemade. It was better for me.

“We couldn’t really afford the Seditionaries clothes or whatever, so we would do the jumble sale, buy a suit, throw a bucket of paint over it, cut it up, join it back together with safety pins.”

I think that’s where I get that attitude where you can use anything, it’s not a money thing, it’s a visual-statement thing. I didn’t really know where to put my creative energy, so I put it on myself, basically – dressing up, dying my hair, making clothes. But I didn’t see it as a job or anything. I just saw it as … going to college without going to college. Education. Educating yourself.

It’s interesting how DIY everything was then. When you started off there weren’t even style magazines as such. These days even the newspaper broadsheets have a style supplement. It’s become boring, almost as if there’s a system that’s been set up for something that was once spontaneous.

There was just such an energy then. There weren’t that many people, really, if you think of the explosion that happened from it. There must have been about 800 in London and 400 in Manchester, and 100 in Liverpool … but because the bands traveled around, we used to see amazing bands together – like The Clash, Siouxie, and The Slits all on for a quid. So there was a lot of camaraderie around, especially in Manchester. The people I lived with, one was a guy called Malcolm Garrett, who set up a company called Assorted Images. Peter Saville was still at college. Jon Savage was up there a lot. And Manchester definitely had its own bands. The Buzzcocks. The Fall. This was everyday for us, so energy-wise it was really happening. Through Malcolm and people like that I learned all about Bauhaus – I’m not saying we were very arty, but it was the energy of the music and punk and the style – but also we were educating ourselves about other movements through the century, the way Jamie Reid was doing a Situationist thing with Malcolm … I learnt so much in those two years just by misbehaving. It was great.

There’s a lot of revivalism going on now of that time, with electroclash and what have you, but it feels like there was more thought and awareness of history invested in it then.

I suppose we thought we were doing something new and different, so we were nicking what we liked from the past and shoving it into the future. The actual media has changed a lot now. Back then it was about photocopying your own fanzine and standing outside a gig and trying to sell twelve copies of it. There was a lot more word of mouth. There’s still word of mouth now of course – there always will be. But back then you really lived for that.

Do you think the crossover happens quicker now?

Well look at Terry Jones and i-D. It did start off as a stapled together photocopy with a colored card cover. And now look at it. It’s really an established thing.

I am very aware that I’m kind of part of that system, and I’m contributing to it even though you wish it could be kept a bit more secret sometimes …

Well I’ve always had that punk attitude, but I did go through that New Romantic thing when I eventually moved to London, which I think suited me more. Even though I enjoyed the punk years, that’s when I started getting a feeling for shocking people even more with your appearance. And rather than when punk became New Wave and became more uniform, that New Romantic thing came from, “Well I don’t want to look like anyone else.” You didn’t want to look like a gang. There was a certain group of characters where you’d drop dead if someone looked the same as you. We spent all day making sure we never looked like anyone else on the planet. A bit more individual I suppose. And then out of that scene there were a lot more talented designers, singers … again it came out of another small group of people and it was interesting to have been involved in both of them. It was still quite small and I quite liked that. I’d much rather go to a really small club full of really dressed-up kids than I would a rave with 8,000 people in it.

That’s what I like about Berlin. It still manages to keep things quite small …

Well as a city it’s always had quite an independent feeling to it. You can look back to the ’20s and ’30s – a lot of the songwriters and the kind of cabaret vibe; I think it’s always had that mixing up of morals and small clubs and so on. Not overground – keeping the underground thing going on. New Romantic went overground really quickly. Probably because it was a depressed time in this country and people wanted … a few clowns. Or whatever we were. I don’t know quite what we were. [laughs]

There’s a story in Boy George’s autobiography where he went round to your studio in Old Street in London to get some of your jewelry to wear at an awards ceremony but he couldn’t decide what he wanted …

… so he wore it all. I know. I saw it on the telly the other day. I really laughed.

So was the Buffalo thing a bit of a natural progression from New Romantic, adding a bit more sportswear to it?

After the New Romantic thing, and while that was going on, Nick Logan was starting The Face and Terry Jones was starting i-D, and the music became more eclectic – you’d go to a club and they’d play soul and mad disco and electro. It wasn’t so much, “Right, I’m a punk rocker and I only like punk rock music” – people’s influences visually expanded a lot more. It went from mad drag to alien. So people were experimenting rather than trying to follow something. And musically punk got me into reggae and reggae got me into soul, and gradually, the older you get the more influences you start absorbing. Especially if you are a creative person, you want to absorb as much of it as possible. So it became more eclectic, and I started enjoying London then. And then gradually the Blitz club thing happened and New Romantic and I latched onto that, “Oh great, something new!” And then came the magazines. I mean we always had fanzines in punk, but when The Face and i-D and Blitz magazines started up, there was somewhere where you could be. And it helped link quite a few people together, not just at a nightclub. Especially people like Ray Petri and Buffalo. Now there’s a man who had an attitude and he built a whole group of people around it – he was the lynchpin of it. It wasn’t just about looking cool, it was about music, hanging out. Galliano and a lot of designers, Leigh Bowery, all those people. It was quite together. I’m amazed sometimes when I think back: you’re standing in a nightclub and you think of the 200 people standing there. If you actually made a list of who was at a certain club you’d laugh your bleedin’ head off.

I heard a funny story about Danny Rampling, when they started off the Shoom! Club during the acid house times. The first week it was an absolute disaster and about twenty people turned up. But by the second week somehow word had got round and they had to turn 200 people away at the door. And he heard someone in the queue say, “It’s alright but it’s not as good as it was last week …”

Yeah. But that’s what I was saying before, sometimes it’s not that many people that can start something quite big off. Because a lot of things are quite corporate now, and there’s so much media around, sometimes it loses its way. When it’s a small concentrated thing, there’s more of a direction to it. It can go in so many directions now. Not that I worry for young people, because there’s always going to be young people and they’ll always have their own shit, but sometimes I think, “Is it too much? Are they actually learning everything or is it just surface?” We really lived it in those days. It was dangerous sometimes going on the street because we looked so bonkers. Now you can channel-hop or go on the Internet and it can be almost too surface. I always say I’m paper, glue, and scissors. I can still send an email – hip hip hooray – but before you had to get your hands dirty. Now you don’t even have to get your hands dirty to do anything.

The thing that really strikes me, particularly here round Camden, and it’s something I’m not into at all and I don’t really get, but these Camden kids that are a bit …

… gothic.

Exactly. But at least they’re living it. And you don’t really see much of it in magazines because no one really thinks it’s cool. But part of me is really glad that’s going on, especially because I don’t understand it.

But that’s another thing also that’s happened with the media: they can invent something now. Whereas before it was young people inventing themselves and the media covering it. Terry and Nick Logan and all those people gave us a format to be in; a magazine. I started off making jewelry, so I was in The Face and i-D and I was a “Straight Up” and all that. It was going on. Whereas now you can look at something like Vogue and it really is just the advertising. It’s not some genius stylist going, “This is a creative fashion picture” – it’s more, “You know we should really be using Gucci again, and we better put a perfume smell even though you can’t smell it.” So it’s turned round, and sometimes it does disappoint me.

I get bored with all these bi-annual magazines with glossy fashion stories that all seem to have hit on the same formula. I genuinely think there are about five magazines out there like that at the moment that are impossible to tell apart. They don’t seem to stand for anything in particular.

Well it’s quite hard to get past the gloss sometimes. It’s so glossy it’s almost reflective – you’re not seeing anything. And things are so retouched for you now. Where are the scars and the spots? Where’s the reality, because it’s so beautifully polished. I never close the door on being influenced by anything, and I can be influenced by a really great retouched photo, but I’m more likely to be influenced by a kid in South Africa photographed on the street with a car he’s made out of Coca-Cola cans. But that’s just me. It can come from anywhere. I’m not one of those who has to sit there every month with all my fashion magazines going, “What shoes am I going to wear?” I’m not like that.

“I can be influenced by a really great retouched photo, but I’m more likely to be influenced by a kid in South Africa photographed on the street with a car he’s made out of Coca-Cola cans.”

We seem to have reached a point where there’s a total domination of “good taste” – but it’s a really mediocre good taste, whether it’s a DIY show on TV or GAP clothing, that sense of attitude has given way to something uniform and bland.

But the media isn’t giving people confidence at the moment, it’s giving them a neurosis and scaring them the whole time. They pick on these themes we know the media’s always been sexist, it’s always been homophobic; now it’s sizeist. It’s not encouraging people, it’s only encouraging them to look at themselves and not feel worthy. And even the fashion business. But the brilliant thing about the fashion business is that there’s so many different people in it. And we all need clothes. And there are some geniuses around, so it’s quite a fertile arena. Same with music – there’s always going to be someone coming around causing trouble …

How did you hook up with the Bristol music scene?

Neneh Cherry and Cameron McVey were very much part of the Buffalo thing, and Cameron was starting to produce and write, Neneh started up and when we did the first album … unfortunately, that’s when Ray Petri, who Cameron and Neneh worked with, started getting ill so they were looking for someone creative. It would have been Ray if he hadn’t been ill, and Cameron was saying, “Who are we going to get to help us?” Because they wanted someone that could do a frock, organize a photo shoot and help do the graphics, find a video director … Because Ray couldn’t physically do it any more he put me up – “Ask Judy to do it, he’s the one you need.” So that’s how I hooked up with them. And when Buffalo Stance from the first album really took off, we were experimenting with people like Mondino – which was a bit to do with Ray as well – and Cam made a bit of money out of it, and then Massive Attack started doing remixes for them, and they ended up recording the demo of their first album in one of Neneh’s houses.

Cam helped them produce it, and then gradually through Massive we met Geoff Barrow from Portishead. Bristol’s not the biggest place in the world, so when we went down there and Smith & Mighty were doing remixes for Neneh, and Neneh was trying to do more interesting 12”s and pull in people from outside the London scene. And with Massive Attack – 3D’s a really creative person but he didn’t really know how to put a great record sleeve together, so that’s when Cameron and the record company brought me in because I could understand where he was coming from but actually help him start off. I found him Bailey Walsh, the video director, because Bailey was an old friend of mine – “Dee, you’ve gotta use this guy, he’s only done two videos …” Just advising them really. It was on that level for me, and I said, “Dee, in two years time you can sack me because you’ll know how to do it, how I’ve had to learn to do it.” And he did!

Are you bitter about that?

No, I’m not bitter at all. That was the idea. I wanted him to do that. I was honest with him. “I’ll introduce you to all these people, and you can bloody do it yourself. You’re creative.” And I suppose that was another thing about learning off Ray, if you can just give someone that extra inch of confidence, then that becomes a foot. And then they’re up and running. Everyone has to learn from somewhere – I learned off lots of brilliant people – I’ve been really lucky with the people that helped me. I still like to do that now if I meet young designers or young people, just to give them that bit extra – “That’s wicked, I love it.” Pass it on. That whole thing about passing it on. You have to.

Can you tell me a bit more about Ray Petri? Everything I hear about him sounds like he was really generous …

He was. Really generous. He was a bit older than the rest of us, and there was something about him. I wasn’t really his style whatsoever, but we became good friends when I was making jewelry Ray used to ask me to come to some of the shoots – “Ooh, can you make me some silver chain stuff” or, “I’ve got this boy, I’ve just found him in a vegetable stall in Covent Garden and we’re going to do a shoot – can you make me a gold bracelet?” So I started getting to know him then, and through people like Mark Lebon and Cameron McVey, Jamie Morgan, just started hanging out with them all. He just had a brilliant way of making everyone feel included, but still directing it. He was always the one putting the tunes on when we were doing the pictures, and making sure the boys were cool – because most of them weren’t really models, they were faces that Ray had discovered, and you know what some boys are like, they just think, “Oh what a bunch of poofs.” And maybe we were, some of us. But he had a way of really giving people some confidence. He was great with me. Even though we had really completely differing styles a lot of the time, he was one of the first people to say, “You should do it. You should do styling as well.” I hadn’t really thought about it, because I was trying to make the jewelry work, but then I thought, “I could do it, I love clothes, I love the visual thing.” And even though my work was nothing like his, he was one of the people who was really instrumental in saying “go for it” and giving you that extra bit of confidence. Everyone who did know Ray still really misses him. I can still bump into people fifteen years later and I’ve never heard a bad word about him. And that’s quite unusual.

“I learned off lots of brilliant people – I’ve been really lucky with the people that helped me. I still like to do that now if I meet young designers or young people, just to give them that bit extra – ‘That’s wicked, I love it.’ Pass it on. That whole thing about passing it on. You have to.”

Especially in this industry – they’re all bitches.

Exactly. He influenced a lot of people without being really boastful about it. Everyone really wants the credit for themselves now, whereas Ray just called it Buffalo and that was a huge umbrella. He wasn’t going, “I’m Ray Petri’ 24 hours a day and I wanna be in Hello magazine” – he wasn’t like that. He was in fact quite a private person but he was doing a public thing. He was really inspirational in getting a lot of people of color into the modeling business; and people like Gaultier have always said he was a big influence. I did learn a lot from him because I do jump around – I jump from fashion to music to whatever, and that’s what keeps it fresh for me after doing it for over twenty years now. I’m not just in the fashion business – you didn’t channel it in one direction, you left yourself open to experiment with lots of different types of media. And then you learn ways of mixing them back in together. When I was doing some of my first shoots for i-D, I was taking something that wasn’t a fashion idea, but whacking it through a fashion editorial. There was one I did on pollution, one on recycling – I tried to do one on the homeless but that was a bit difficult. And I think I got a bit of that from him, from that time where you mix your media up and then try and invent a little thread of your own.

Do you think things have changed for the worse?

People are a bit more self-obsessed now, so they’re a bit more guarded about what they’ve got. But I still find people that I think are amazing. I’m in a privileged position where I can now meet people who are my heroes. I loved working with Iggy Pop because I grew up with his music, so that was a massive moment for me. But now people are a bit more, “Well that’s mine. And I don’t want to share it really.” That’s why I’ve virtually stopped styling now, because it’s so competitive, and it’s really bitchy, and there’s always someone that’ll undercut you. And basically they’re just glorified shoppers now. When I started it was Ray Petri, Amanda Greive, Camilla Nickerson, Venetia Scott – it was a small group of people but we each had our own individual style. Even now, I haven’t done an editorial for eight months or so, but I’ll still do one, and boy will it stick out. But I don’t see why I have to do one every month just to get an advertising job and then style some dodgy show in Milan. For loads of money. And then just kiss ass. It just doesn’t suit me. I don’t see the value in it.

What do you think of this whole trend now of the “Super Stylist”?

But it’s not just the Super Stylist, it’s the Supermodel, it’s the Super Designer, it’s the Super Lifestyle. The Super Sportsman. It’s not really real. Anyway, sometimes I worry that it’s not about talent, it’s about who you know and who you’re going out to dinner with.

It’s about networking?

Yeah, it’s networking, but it’s not networking with talent. I suppose there still is a kind of camaraderie, but it’s not built on much substance. You hear about stylists working for designers for two seasons and then they boot them off. It’s happened to me. It’s happened to everyone. And all of a sudden they’re in with another designer and that lasts for two seasons. There’s nothing stable about it, it’s so precarious. And you have to spend so much time networking for the amount of time you’re physically grafting and trying to do something different. And a lot of time they don’t want something different, they want someone to say “Yes,” rather than, “Oh that’s awful!” They don’t really want an opinion, so it’s all this dodgy game of good manners or something. Not dangerous enough for me!

You mentioned the Super Sportsman – if you look at David Beckham, even a few years ago the average football fan would say, “Oh he’s just a poof in a skirt,” but now he seems to have made it acceptable to show a bit of effeminacy in what is a very masculine arena, and those same people now look up to him.

He can have a haircut and then 200,000 people have that haircut. I can’t really criticize it. I think it’s like watching cartoons, especially those two. It is like an ongoing cartoon. They should make a cartoon out of them too. But at least he’s got talent. That’s how he gets away with it. He’s a bloody great football player. Everyone takes the piss out of her, but if you do have genuine talent they can’t really rip you to shreds. And he’s got that unusual talent of being as camp as a row of tents … but he can score goals, so he’s got this weird balance. Maybe it’s something new for some people. So a straight lad in Leeds can look at him and not want to beat him up on a Friday night because he’s wearing something like that – because of something else that interests him. It is a phenomenon I suppose. Which is not a bad thing. But I’ve never been into mass movements – me and the general public have always had quite a dodgy relationship. I’ve always had – cliquey’s not the right word because it sounds exclusive, but I suppose I’ve always gone for the like-minded I suppose.

Derek Jarman seems to be one of those like-minded people who had that same attitude towards the general consensus but was still hugely influential …

I was working in a nightclub when I met him. When the New Romantic thing started I’d been working in publishing for a couple of years. It wasn’t the creative side, it was the production side – getting the magazine to the printers. Which was really interesting. Boring magazines, but I made good money at it and I worked long hours, so it taught me a lot about discipline. And then Heaven opened, the nightclub in London. And me and my friends all got jobs there, doing coat-check. And one night Derek came in and we got chatting. I was always really dressed up so he was interested in that. And then he asked if I was interested in being in some Super 8 stuff for him. He did pick me up basically, but it didn’t work on that level, and then we just became good friends. And he really encouraged me and introduced me to some really interesting people, and I used to help him do his movies. He was another one like Ray who, with no reward to themselves, would say, “Oh, you wanna do that. I know someone who can do that. Well, let’s go and have tea with them!” Just to keep things moving. He was really like that. He was really instrumental in helping loads of young filmmakers. And dancers, artists, prop people. He was the link for introducing people that maybe wouldn’t have met otherwise. Their paths may not have crossed if it hadn’t been for Derek or Ray.

I looked you up on the Internet movie database, researching the Derek Jarman films you’d been involved in, and it lists you as “actress” and says “Judy Blame as herself.”

Oh yeah? Great. [laughs] There’s this funny story – a friend of mine was in that second-hand shop Relic, that this guy Steve runs. Steve’s always been a mad collector of my stuff, and apparently Dolce & Gabanna went in there and said, “This Judy Blame, we need to find everything of HERS!” Steve was like – “No sale!” [laughs] “Bugger off!” I mean they ripped it all off anyway so it didn’t matter. It helps having a funny name. It’s great on the phone when people say, “Can I speak to Judy Blame?” and you go, “Speaking.” You’ve got the upper hand straight away!

Is it right you chose the name because of Judy Garland?

Basically when I worked in Heaven I had this mad hairdo that was a messy black, piled-on-top–of-the-head thing. And I was messing a lot with gender at the time. So I could be wearing a pencil skirt and a shirt and tie, mixing all that up. And this designer called Anthony Price used to come down and he and his friend used to joke about me – they didn’t know me but they used to see this odd character wobbling through the nightclub, pill in one hand and cocktail in the other, and they nicknamed me Judy. I didn’t know this for months. And then one day I finally met Anthony and he called me it to my face. And I’d just started doing jewelry and I didn’t want to use my real name – it didn’t mean anything to me really – and another friend of mine, Scarlet, came up with the Blame part. I didn’t think it would be a permanent thing. I thought of it like a B-movie actress that dies in a car crash after making three movies – that’s how I felt about it when I invented it. But it kind of stuck. [laughs] Unfortunately.

Credits

- Interview: MARK HOOPER