Fuck Morrissey, Here’s Linder

|EMILY KING

Born in Liverpool, LINDER STERLING studied art and design at Manchester Polytechnic in the late 1970s. She was in the year above the graphic designers Peter Saville and Malcolm Garrett, and in 1977 Garrett used a photomontage she had made for the cover of Buzzcocks single “Orgasm Addict,” a piece that has since become one of punk’s iconic images. In 1978 Linder formed the band Ludus, joined in 1980 by Ian Devine. At a performance at Manchester’s Hacienda she wore a dress made of meat with a dildo as a means of satirizing the club’s policy of showing pornography as entertainment. The evening remains a seminal moment in the history of sub-cultural Manchester. Ludus were signed to the Manchester label New Hormones and also the Belgian label Les Disques du Crepuscule in 1982, but disbanded disharmoniously soon after.

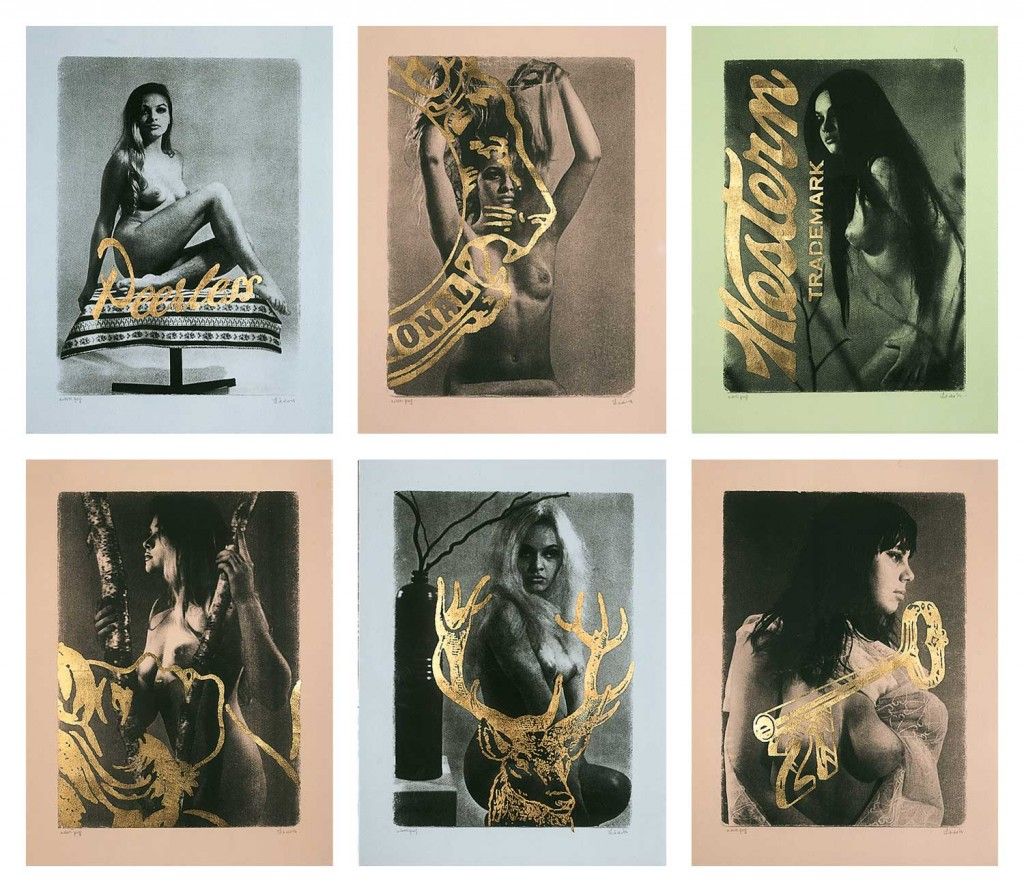

Possibly most famous for being Morrissey’s best friend, Linder is also celebrated for her uncompromising feminist collages and more recently her installations and performances, many of which take place in a psychic territory she calls Linderland. She took part in the 2006 Tate Triennial with a performance that pitted three Northern rock groups against a dozen women performing Shaker rituals.This work is part of a dual fascination with a model of masculinity epitomized by Clint Eastwood’s appearance in the films of Sergio Leone, and a form of quiet female resistance represented by the founder of the Shaker movement, Ann Lee. The last 30 years of Linder’s work is being celebrated in a book published by JRP-Ringier in Spring 2006. Bringing together a disparate cross section of her output, the book includes collages, images from performances, and Ludus ephemera. Linder hopes that it will end the long-running confusion as to who she is and what she does.

EMILY KING: What was it like at Manchester Polytechnic in the 1970s?

LINDER STERLING: When you are young, and in a city, and interested in art, and have an art college at your disposal, it’s very exciting. When you’ve spent your whole life looking for an escape route; you want to try everything at once. I went into the Fine Art Department, thinking, “Here we are – Art!” But in 1974 in Manchester, that department was all about abstraction; it felt so alien. And then as I went to the Graphic Design Department, it was all very sleek and glamorous. In the end I chose to study illustration.We were fortunate because the tutor came from fine art, and basically she adopted me and allowed me to do what I wanted. She encouraged acceleration and inquiry. During the summer of 1976, the Buzzocks played with the Sex Pistols and the Clash, and so we ended up staying at Malcolm McLaren’s flat. By the time I came back to college in September ’76, the transformation was complete. I was wearing very beautiful bondage trousers from Vivienne Westwood’s shop, SEX. Malcolm [Garrett] and Peter [Saville] were quite astonished. So I took them by the hand and said, “Buy these two records.” They were the Ramones’ first album and The Modern Lovers. I led them forward, but perhaps they tell it differently.

I can imagine Malcolm in bondage trousers, but not Peter.

Yes, Peter was more, well, Peter. In the clubs in Manchester, one week young boys would be wearing white shirts, and the next you would see the same white shirt, but it would be ripped, safety-pinned and have paint on it. Other people would change their look from week to week, but Peter would stick with the white shirt.

When did you start to perform with Ludus?

It was around ’78. In Manchester at that time the gap between standing in the audience and being on stage seemed very, very tiny. It was quite natural for the people in the audience to be up on stage a week later trying to play guitar. It was something you just did. For me it was a natural progression. It didn’t feel that dramatic, although it sounds quite dramatic now.

So you weren’t trying to become a pop star?

No. No notion of that.

Was Ludus an art band?

No, I was the only one who had come through art school, nobody else had. It was very different then, a lot smaller scale. By the time Ludus ended, I can remember thinking, “I can’t go anywhere else with this now.” I had a sense that we had really taken it far enough. It was at the end of ’82, and I think we played only once or twice more. I went to Brussels for a while to record on a label called Les Disques du Crepuscule. If you mention that label now to a certain age group, people still get dreamy-eyed.

Ludus ended very dramatically, didn’t it?

Only in the sense that life was too perfect in Brussels. We just couldn’t write; we couldn’t create. Whether the necessary grit was missing, I don’t know. But we would sit at this beautiful concert piano in a beautiful concert hall for hours … and nothing happened. Absolutely nothing. And so the relationship between Ian [Devine] and I really degraded. I had wanted an escape route in Brussels, and it was a kind of fairy tale in its beauty then, but I was so miserable.

Had you been trying to shock audiences?

The performance at the Hacienda was very much about shock. We wanted to return to really strict three or four minute songs, pop songs that were lyrically provocative.

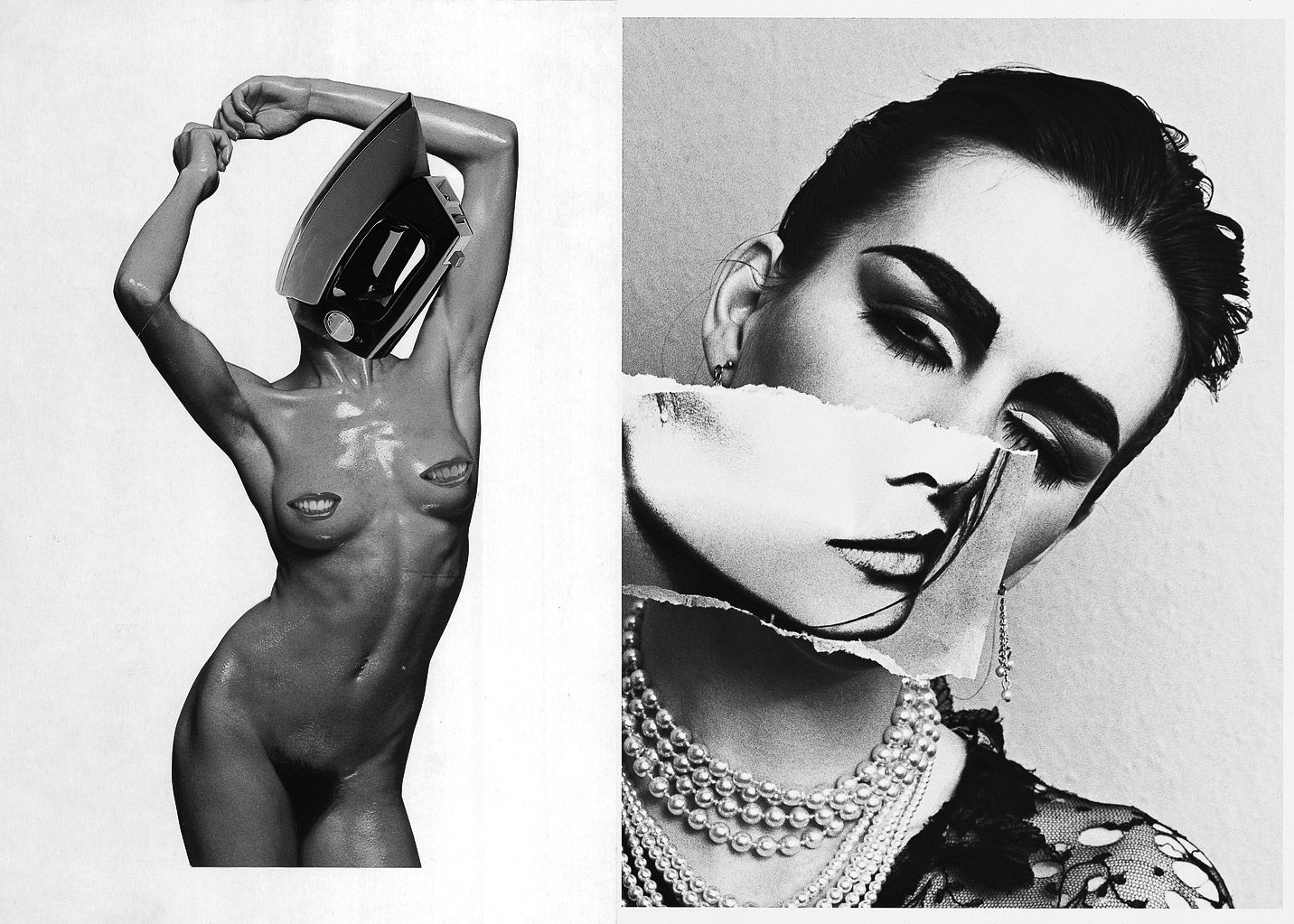

I am interested in the impact of your collages using porn images. Do you think that it has changed now that porn has become so ubiquitous?

Doing the book has made me look at them again. I have to choose how much to contextualize them. When I was doing the work in ’76, in my last year of art school, pornography was still shocking and covert.

Now the models do look kind of innocent.

Yes, they didn’t, but they do now. There’s a series called “Pretty Girls.”

Is that the one with girls doing things with domestic objects?

Yes.

It looks kind of Victorian, modest almost.

It does, doesn’t it? But 30 years ago that’s what pornography looked like. And it was what women’s bodies looked like, they still had dimpled flesh and lots of pubic hair.

And the breasts weren’t so round and hard.

Women’s bodies weren’t that manipulated then. There is a lot of innocence to it, or at least that’s how it appears now.

Has that changed the meaning of the work?

I wonder about that – how people will look at it. At the time people were generally very shocked by those images, it will be very interesting to see what the response will be now, as the monograph is published. In those days they were very potent images. It’s a shame that they’ve had to incubate for 30 years.

Did people see them as feminist imagery?

No, they didn’t. When I first made those montages, the Left-wing bookshops wouldn’t touch them. So I am finally able to produce my document of protest, but it has become a historical document.

Were you reading feminist texts at the time?

Oh, I never stopped reading, but I think when it comes to the work, my approach was very intuitive. The work was about anesthetizing the intellect. I don’t work too intellectually because then it becomes too dry.

Were your collages meant to raise political awareness?

Well, we had all read John Berger’s “Ways of Seeing.” I was definitely trying to raise my own consciousness, and that wasn’t an easy job. So there was the intent, but then you just do the work.

Do you try and effect change through your work?

Yes, I do. The piece at the Tate is very volatile. It’s a piece where I just let go of control. I have no idea what’s going to happen over four hours, and it might be boring or spectacular. So it feels like a quiet protest.

Thinking about that piece, I wondered if you identified with Ann Lee?

I work with archetypes – Leone’s Clint Eastwood character is the Man With No Name, and similarly Ann Lee becomes the Woman With No Name – so, of course, within those archetypes there is some identification. Something resonates potently in the psyche. I hope that the collective unconscious is running with me this time, but sometimes you make work and it doesn’t catch the public imagination for 20 or 30 years. The Return of Linderland is about paradox, creating a balance between a malign male presence and a spiritual female absence. The piece works as long as you don’t fall to either of the extremes. It’s a tight rope walk.

How does Shakerism combine with Northern working-class culture?

Ann Lee, who founded the Shakers was born in North Manchester and the movement began there. Of course I could have made a piece about Shaker ritual that could have been quite sanitized and exquisite. We know that aspect – we know about the beautiful furniture and the piety. This is a reminder that it came out of something far more volatile and violent, from a hellhole of Manchester in the late 18th century. Although the Shakers were always very open and invited the world to come watch their dancing; people were quite hostile, imagining horrible machinations, a little like people later imagined punks in the late 1970s. There isn’t any marker of Ann Lee’s life in Manchester. No plaques, nothing. I was very interested in Ann Lee as an iconic female absence.

Do you fear being consumed by the art world?

No, because I don’t think it is able to consume me. I think people have problems positioning me, and identifying what it is that I do. Of course, I presume the monograph will add to the confusion.

I was thinking about your outsider status, that you seem to treasure it.

I don’t see the art world as a threat. But I think the position of an outsider is quite uncomfortable. However romantic a notion, real outsiderdom is lonely.

When was your first gallery show? It was fairly recent, wasn’t it?

Yes, I suppose. Perhaps in 2000, at the Cornerhouse Gallery. My contact with the art world has all been through really fantastic individuals – curators like Paul Bailey. At that time he was the one curator who said, “Fantastic, whatever you want, just come and do it.”

Was that a local urge, having to do with Manchester?

He had known about me for a long time anyway – from Ludus. I think it is more of a reflection of Paul Bailey and his absolute fascination with the arcana of British culture.

Do you think gallery-goers now are the same people as record buyers were in the late ’70s?

Yes, I think so, to some extent. Younger artists are constantly name-checking people from my generation, for good or ill. It’s interesting that my generation provides a sort of palette for inspiration. It was the last years of the British underground. Everything is too institutionalized now, which is why perhaps a lot of younger artists now look to that period – they long to have an underground, which is probably impossible for their generation.

And what did you do in the ’90s?

The ’90s were tainted by the culture of irony and ladism. Towards the end of the ’90s I found a phrase that was the momentum for “Linderland”: “And … the ironic shall yield to the mythic again.” It is a line from a Larry McMurtry essay, written in 1966, about the idea that culture goes round in circles and sooner or later people will start to wonder about that which is larger than themselves. So I took it to mean that those years of culture, years that I found quite arid, would pass.

When did Linderland emerge?

I think it was about ’98. The impulse was very simple. I had read about a group of American housewives who all had the name Linda. They’d meet once a year and form “Lindaland” and eat Linda cake. I thought it was fantastic. I wondered what my own Linderland would be like. I have always been very interested in names because of that punk thing, the significance of who is allowed to name who.

When did you become Linder?

I was born in 1976.

Before you were Linda?

Yes, punk allowed you to re-christen yourself and be re-born. Proclaiming Linderland then gave me a psychic territory, a home and a landscape …

So Linder was a more accurate description of you than Linda?

Yes, it was, because it had a fairly Germanic spelling and we were very conscious of the relationship between Weimar Germany and England in the late ’70s – Heartfield, Hoch, Dix, Grosz, and Fritz Lang were all vital. I was also studying people like Wilhelm Reich – whom Patti Smith wrote about on Horses.

And Linder, was she a pop star as well?

In those days, I never thought about being a star – it just wasn’t a word in our micro-cultural vocabulary. The intention of course was to make music that would not be so pretty. Any glamour was there to serve as a Trojan horse.

Did you ever work formally with Morrissey?

Only in the sense that in ’92 I bought a camera and started to take a lot of photographs and he asked me to come photograph his world tour. I had a young child, so I said I would photograph sections of the tour. I also sing a backing vocal on “Driving Your Girlfriend Home.”

You sent me a written piece about your involvement in the Manchester music scene in the late ’70s and early ’80s, and that gave me the sense that you are a bit bored of talking about it.

Yes, I get contacted by so many journalists now wanting to write their own history of punk, and so I wrote that piece to at least put one female voice in there. Otherwise we are still so easily written out of history. I think a lot of men get quite very proprietorial about the history of that period. There are still virtually no books about the history of pop and rock culture written by women.

In the ’70s you called yourself a feminist artist.

Absolutely. Yes I was.

Making assumptions about your youth, but didn’t you feel outside of that “authentic” working-class culture when you were growing up? Did you feel different?

Constantly. But as you look back you think, “Of course I should have been there.” We were perhaps the second generation within the working class to see that there were other possibilities, but we weren’t quite sure what they were. There was a glorious sense of another world, better than the one we were in, but just out of reach. So first I retched, and then I reached.

What is your arena of concern now?

I can only speak for the work I am currently making, and that is primarily to do with acquiring an absolute authenticity of expression – to make something that is free of “style”, and simply itself.

Do you think this is a more general problem in culture?

Yes, there is a homogenization process going on. In seeking to melt the boundaries between media, a lot of culture has become diluted. And this is why the musicians I am working with are pure rock musicians – rather like the pick-up bands used in the 1960s. They have no interest in being “art," they just want to rock. It’s their job.

Credits

- Interview: EMILY KING