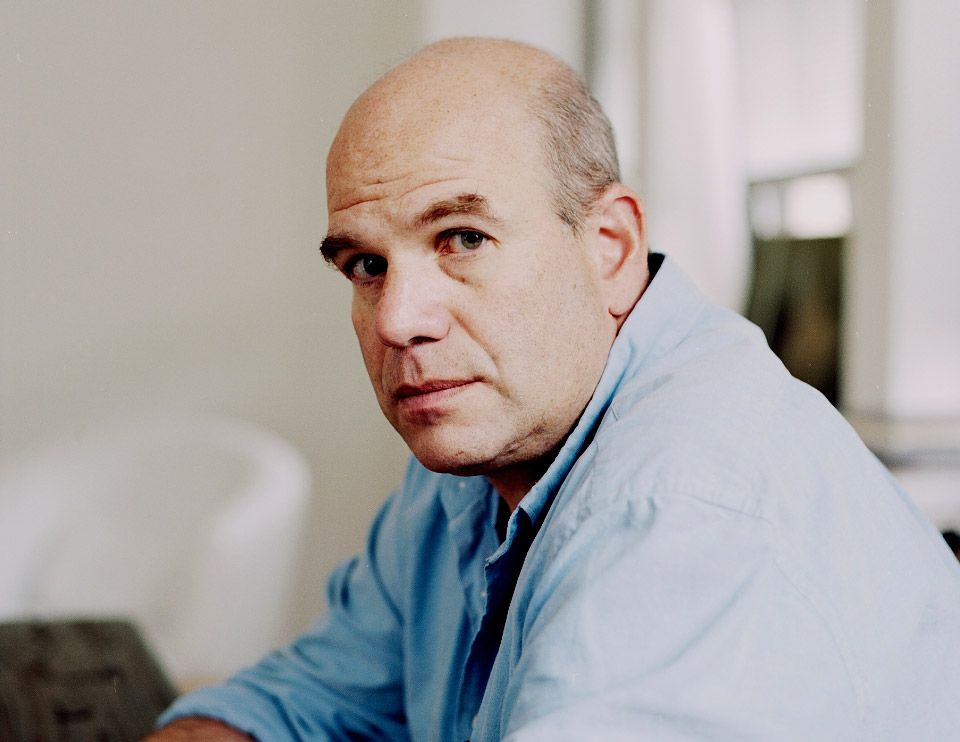

Japan’s Master of Gay BDSM Manga GENGOROH TAGAME Opens Up to 032c

GENGOROH TAGAME is perhaps the most influential gay manga artist in the history of the Japanese medium. His work often includes scenes of BDSM, torture, and humiliation between hyper-masculine, bearish men, and is notoriously difficult to track down outside of Japan. 032c spoke with Tagame ahead of his first solo exhibition in Germany, which opens this Friday at xavierlaboulbenne in Berlin.

Gengoroh, I can imagine you’d like Berghain. Have you been? What did you think?

Last Autumn, I visited a sex club called Lab.Oratory, and also visited Berghain beside it. I really enjoyed these atmosphere, especially the dark and hard mood of the sex club!

Can you speak about gay Japanese publications such as Fuzokukitan and how they’ve influenced gay culture in Japan?

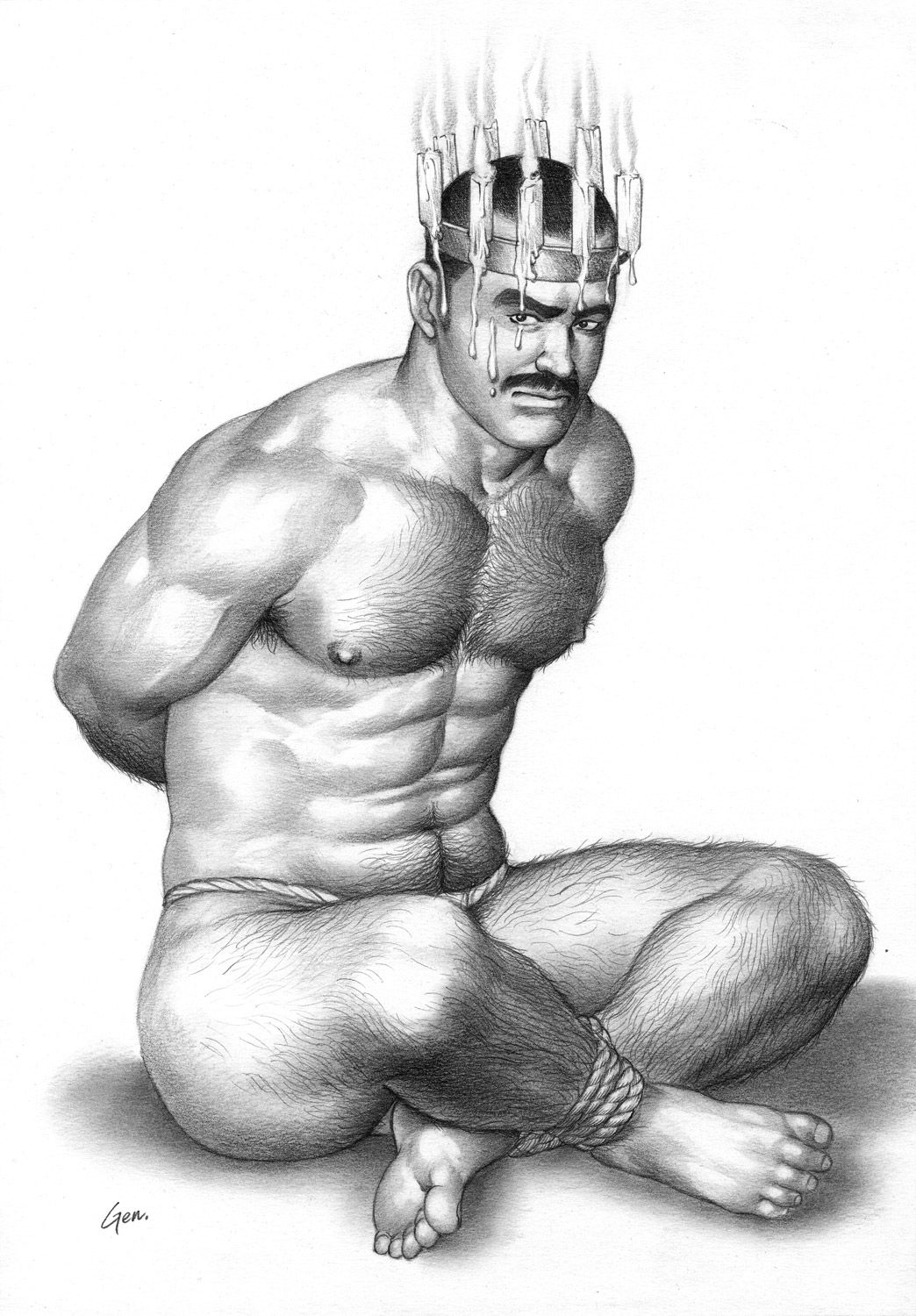

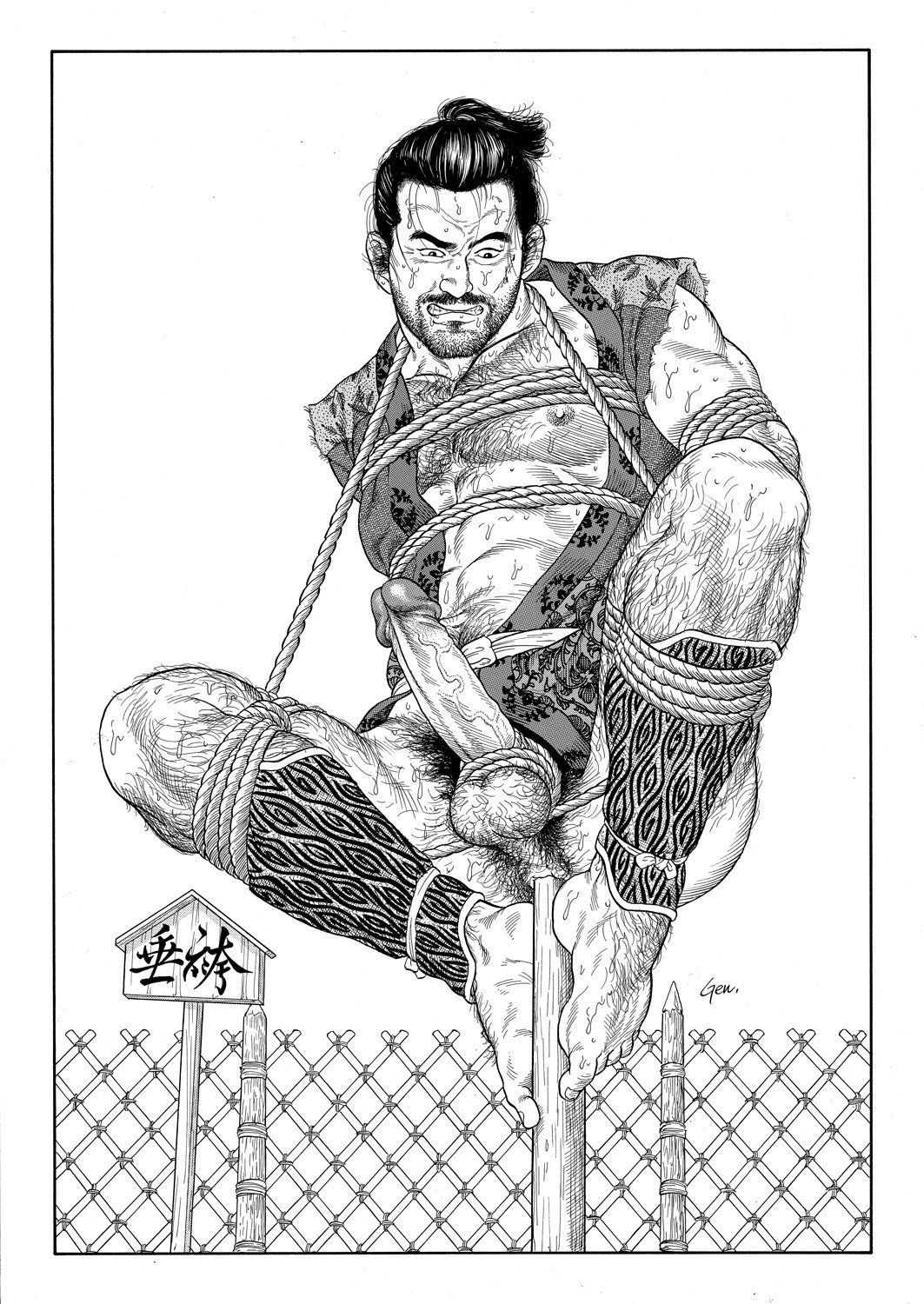

The story of contemporary gay erotic art in Japan starts with the magazine Fuzokukitan (1960-1974). Fuzokukitan included all sorts of kinks, both male and female: S&M, fetishism, homosexuality, lesbianism, and transvestism. In short, it was for abnormal sexualities. There were similar magazines, but Fuzokukitan was the most important. It differed from the others with regard to its cover art from the start. While the cover of the other magazines only hint at S&M play by heterosexuals, Fuzokukitan used male nude art on the cover three times a year, one out of four issues, from 1962 to 1964. This produced a sort of first generation of ‘男絵 otoko-e‘ (male pictures) artists. The recurring elements to these artists are the rather sentimental, sorrowful looks; images of men with cheerful smiles are not to be found. The motifs were often based on the darkly spiritual male beauty from samurai or Japanese gangsters genres. Influences from Western gay culture were rarely seen.

From the 70s to the 80s, gay magazines grew rapidly. In 1982, a new gay magazine called Samson was established. In the beginning, it was a general, gay interest magazine, dealing with all kinds of body types just as the other gay magazines did then. Later it specialized in more niche sexualities such as “chubby chasers” and “daddy lovers.” Thanks to this change, it supported gay artists who specialized in certain fetishes, which was uncommon up to that point. This produced a second generation of otoko-e artists. The style of these artists varied, but generally the darkness and sorrow faded in the images. This is due to, I think, a freeing of the gay community from its guilt, as society had begun to become more accepting. As for motifs, samurai and gangsters decreased in number, and sportsmen increased instead. The objects of gay sexual fantasies shifted from spiritual beauty to physical bodies as time went by. As for fetishistic symbols, in addition to traditional loincloths and tattoos, motifs which were influenced by European and American gay culture, such as jock straps, thin tank tops, and leather fashion decreased in number. It was also during this time that gay magazines started featuring comics.

In the late 80s and early 90s, gay life began to be featured in more mainstream media in Japan, and not exclusively relating to sexuality. Japanese art magazines also began featuring gay artists from Europe and the US. As a result of this, there’s been an widening of influences to the point where gay niches emerged catering from everyone from teens to seniors.

Can you tell us a bit about the history of bear culture like in Japan? How does it differ from Western perceptions of hypermasculinity?

Actually, I’m one of the originators of Japanese bear culture. When I started my career, a man with a beard was very rare, even in the gay community. I believe that I’m the first one who used the word ‘熊系 Kuma-kei‘ (bear type) in the context of Japanese gay culture. When I started to use the word, I didn’t know much about the bear culture in Western world. So my ‘bear type’ was masculine, bearded and hairy, but not necessarily ‘chubby’.

Before me, there weren’t any Japanese artists drawing bearded and hairy masculine guys as an idea of a sexual fantasy. After the word Kuma-kei became popular in Japan, some began drawing bigger guys than mine, and their drawings were closer to Western bear culture than my works.

But the situation changed a little by little. Now it’s much more common in the Japanese gay community. Some people say it is the influence of my works, but I don’t know.

Tom of Finland’s work looks like something out of Disney beside your illustrations. Do you think this is one of the reasons why your work has been so difficult to find outside of Japan? Have you run into censorship problems in the West?

It might be one of the reasons. My works often include heavy BDSM content and non-consensual sexual acts. I’ve been told several times by Western publishers that publishing some of my work in their country would be difficult. But I’ve never faced censorship problems in the West, mainly because editors have never even tried to publish my ‘risky’ works. So in this regard I feel more affinity towards artists such as Etienne, The Hun, Cavelo, and Les, than I do with Tom of Finland.

I noticed you’ve also begun creating 3D renderings. What is it like for you working with this medium as compared to paper?

I tried 3D CG for a while, but I’ve lost interest in it for the time being. I’m always wanting to brush up my skills and to try new things. But I’ve loved drawing images on paper since I was a child – that’s where I’m at my best.

Tagame’s solo exhibition opens at xavierlaboulbenne in Berlin on Friday, March 7th and runs until April 20th.

Credits

- Images courtesy of: Gengoroh Tagame and xavierlaboulbenne, Berlin