“Punk Metal, Babes”: ENRIQUE AGUDO Explores Identity, Sexuality, and Mythology in VR for a Digitized Tribeca Film Festival

Like many large-scale events this spring, the Tribeca Film Festival could not take place amid the Covid-19 outbreak in New York this year – at least in its live iteration. Instead, the festival – founded in 2002 in an effort to bring cultural activity and energy back to the Lower Manhattan neighborhood following the events and impact of September 11 – went digital, expanding its platforms with online interventions and, as a result, its explorations into new media and technologies. World premiering among the projects featured as part of Tribeca 2020’s immersive Cinema 360 program is The Pantheon of Queer Mythologies, ENRIQUE AGUDO‘s VR world of collective of deities that “present a way to question, empathize, celebrate, repent, resist, consume, abstract, identify, regenerate, and love in complex times.”

Agudo’s artistic practice, informed by his background in architecture, takes place at the limits of digital media, taking form as speculative world-building, research-based fictional narratives, and anthropological investigations of identity and sexuality enabled by new media and animation technologies. Here the artist considers how VR relates to – and might serve – queer cultural production, contemporary folklore, and the creation of environments and identities.

Can you say a bit about what brought you to Oculus / VR technology in your creative practice?

I have an academic background in architecture, and a professional background in new media art, so VR is the natural step for me to explore the spatiality of architecture versus the visual storytelling of technology-centric art. Architecture and VR are sisters: one grows up to make their parents proud by fulfilling societal expectations and the other becomes a punk metal head. In its pragmatic form today, architecture cannot be truly revolutionary because it exists in a socio-economic reality that never happens for its own sake. In its conceptual form, architecture currently relies so heavily on object-oriented ontology and generative and digital prototyping tools that it might as well be sculpture. However, the ideas that we speak of in the field of architecture can be explored through new media because they become detached from the system, at least in the process of development. The compromise is usually never between the creator and reality, but between the creator and the medium, which is where virtually reality is today.

The world of art, however, is only permeable through institutional chaperones, who are still very skeptical about new media. The conservation about digital and technological artwork, for example, makes galleries and their clients fearful that their investments will devalue progressively until the work expires. Virtual reality is a medium at its genesis. The immersive aspect embedded in the format connects to performance and installation art, and film has become a cheeky, yet fortunate benefactor. Gaming systems like PSVR, Valve Index, Oculus, or HTC Vive are setting up platforms that allow for immersive and interactive entertainment models. We are still at a place where VR has not taken root universally, and although it eventually has to fit into the socioeconomic framework that we live in – or that we will be left with after Covid-19 – VR still has no clear global business model attached to it. So we can still mess around with where the medium heads next.

How have you approached the medium specifically as a means to engage a queer cultural discourse?

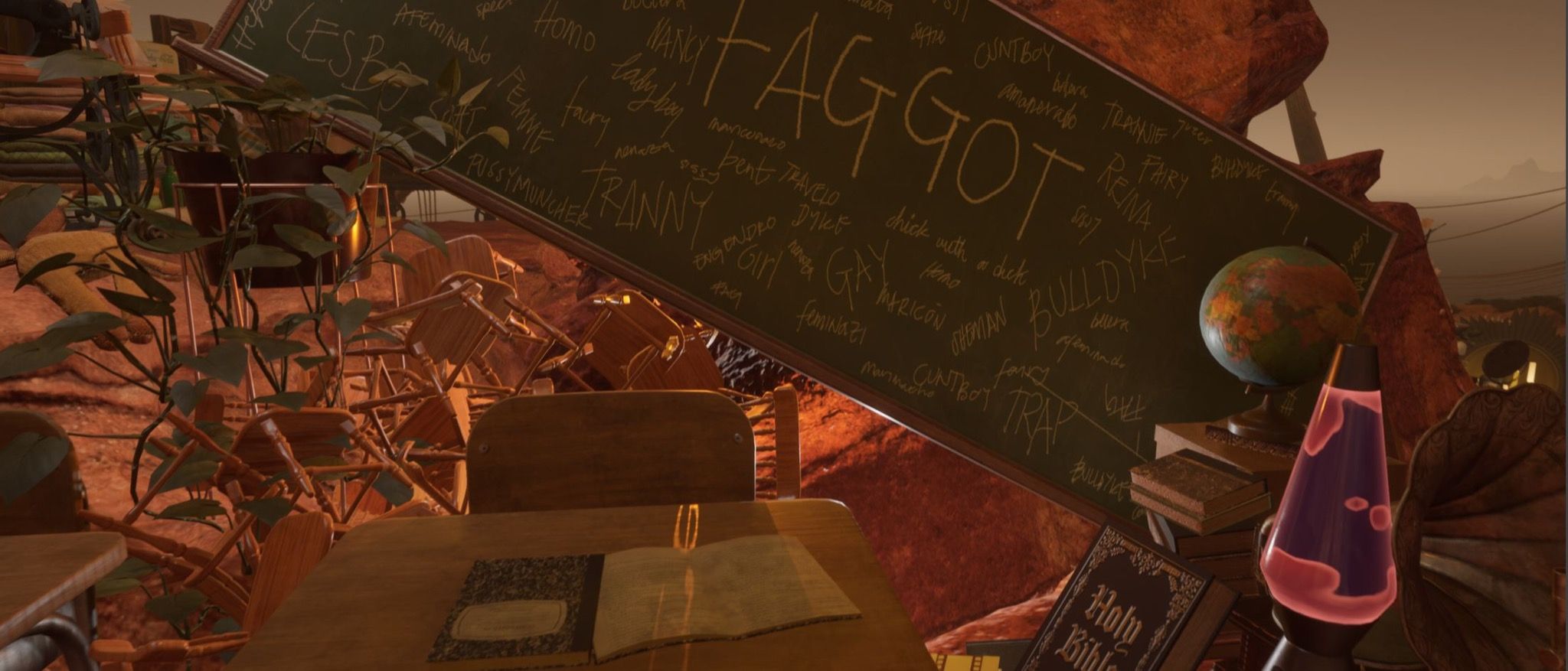

When this project started to form, I started to think about how queer identities ought to be represented, and thought of this as a perfect window of opportunity to make VR a medium for queer narratives. Queer representation in art and culture that is purely celebratory is only very recent, and the window of empathy from mainstream culture toward queer stories has only begun to happen in the last few decades. The possibility of bringing a universal audience into the parallel worlds of the complex sum of parts that is the LGBTQIA+ identity umbrella also creates an opportunity for that audience to identify both more broadly and more concretely, to care more personally, and to respect more lovingly. As immersive media takes deeper root in our cultural and artistic paradigm, hopefully this work, and other queer cultural artifacts, can act as a cornerstone, because the empathic power of taking the viewer into the film makes VR technology the perfect channel through which to empower narratives of those who are often less seen.

I started making this project with the intent of creating something beautiful that might pay homage to the queer heroes of history, through a representation of what it means to be queer today. These stories aren’t all mine to tell, however: my experience as a cis white gay man is privileged and limited, so I made sure that I teamed up with extraordinary people who wanted to make their voice heard and their lived stories known through this project. GRACIE CARTIER, for example, is a beautiful woman who has lived in Hollywood as a straight man, as a gay man, and as a trans woman. Her story of endurance defines the deity she becomes in the Pantheon, Griyah – in many ways, she is that Goddess already. Technology plays an important part in this: I want to make characters and environments that weren’t exclusively digital, and that were accurate personifications of the issues being explored. My creative direction was always in service to their story, because I wanted to make sure that their experiences were the central driving force, and so we used photogrammetry to scan the cast to bring physicality and integration of the virtual and physical, so they weren’t mere digital avatars.

Most platforms are built and coded by cisgendered white men. What challenges does that pose, and how do we queer it?

Queer stories in their full complexities, as opposed to those aiming to satisfy a primarily straight audience, can be inconsistent and conflicting, and don’t always tell a clear or linear story. The heteropatriarchy doesn’t understand that because it has not questioned its identity from the most visceral sense. Think of how different the world would be if Tolstoy had made Anna Karenina a trans man, or if Juliet may have fallen for her cousin Rosalind, instead of Romeo. So it is difficult to imagine that a system that gave rise to virtual interfaces from a white male privileged perspective could be easily dismantled. I think we have to make work that brings these issues to the forefront. People like Sam and Andy Rolfes are doing this kind of work, and so is Jacolby Satterwhite, Pussykrew, and Frederick Heyman. These people are using existing platforms to make experimental expressions of identity and ideas of self, whether that is using animation, VR, mixed reality, or interactive performance. The revolution needs to seep in ideologically so that a paradigm shift can take place and the structural reform can happen without violence. I hope I can join with my own small contribution.

How is this technology particularly suited to the mythological content of the project, would you say?

Myths are allegorical stories that represent conflicts, hopes, and lessons of different societies that are fictionalized to be universal: we can project ourselves onto mythologies, which thus transcend generations. Queer characters are celebrated and normalized in these tales – most characters are heroes, goddesses, gods, or other deified figures who evade moral norms, or whose moral integrity is simply implied in their status. Hindu mythology has represented deities who experience gender variance and queer sexuality, even a third gender. Norse mythology attributed morphing gender presentation as something casual and in their power. The Amazons famously lived on an island free of men, who were only engaged for the purposes of reproduction. Each story’s purpose is achieved through allegorical means, which itself is achieved through queerness. There is no suppression, no vilification, no estrangement. It is not an arbitrary choice, then, to represent the conflicts, hopes, and lessons of queer voices today applying the same techniques within a contemporary medium, such that they, too, can become universal.

How do these queer and mythological frameworks connect to the notion of world building, which has been on a lot of our minds in these past weeks of isolation, for example with the explosion of world-building games like Animal Crossing?

The notion of world-building has been around since the Pleistocene. We imagine and visualize alternative worlds as a means to understand our own environment in new ways, to stand outside of the familiar and be able to see it with fresh eyes. Unfortunately, when we self-mythologize today, the story we come up with about who we are and what we aspire to be seems to be stuck somewhere between Orwell’s 1984, and Paltrow’s GOOP.

That is why I think the mythological and the technological will continue to evolve in tandem. Contemporary culture is infused with digital imagery, and my work focuses on recognizing patterns in these digital indexes to shed light on how they affect the way we behave. We see the world through digital interfaces, and by extension that is how we understand ourselves. This notion is both alarming and thought-provoking. I’m interested in telling stories that can empower people to make choices about the cultures that they are a part of, to shape the direction of those cultures. I want queer identities to be included and virtual reality makes that far more accessible. Being in its early stages, it has the potential to be the first medium to be inclusive and intersectional from its origin. Imagine if the VR of the future includes celebratory stories of diverse and complex identities as a starting point. The process of world-building is the way we can achieve that.

Generally speaking, how do the technological and the spiritual relate for you?

I think there is a difference between the mythological and the spiritual, though there is overlap. However, the question of spirituality and technology is incredibly interesting to me, and relevant to this film. I think places of worship will become places like Zoom, and figures we worship will be figures like Lil Miquela. The concept of “followers” already suggests a certain deification of brands, people, and things, and as the worlds of VR and AR become more immersive, our metaphysical experiences will likely be deeply rooted in technology. We already turn to Google for the things we don’t know, Amazon for the things we need, and tweet and post our thoughts, our prayers. We accept cookies, agree to terms of service, and enable locations services. In a way, the internet is an all seeing, all knowing, omnipresent entity that holds our hopes and dreams and can potentially grant us anything, if we manage to get enough views or clicks. The structure in charge of developing machine learning and AI technology is even a bit like traditional Abrahamic religions: patriarchal, managed by a secretive elite, and driven by surveillance.

This project aims to be a celebration of otherness, a celebratory account of contradiction, imperfection, vulnerability and concern. Those are human qualities that don’t translate to tech as we know it. Spirituality is an irrational experience, and despite the overflow of scientific data available to us, there is a part of us that still wonders about the intangibles and unknowns of the universe. Our ability to experience transcendental states – be that on the dance floor at Berghain, at a silent retreat in Cambodia, or in a VR film about queer deities – is deeply personal, and can be tapped into despite whatever governing structure or socioeconomic framework we inhabit. I think spirituality ought to be the driving force behind technology, not the other way around. As we approach a dystopian future of AI, buildings without people, ecological disaster, etc., we might want to harvest technology that fosters the spiritual as a way to connect with ourselves.

What limitations, if any, did you encounter while adapting your ideas to the platforms and formats of VR and/or Oculus specifically?

One of the biggest challenges is the technology itself. VR headsets have been heavily dependent on strong computer power as well as trackers and they often flicker in and out, sometimes lagging slightly or desynchronizing. We can think of VR today as being a 1990s Motorola phone. When Apple releases a headset that is user friendly and powerful, the world will change. Oculus are getting close with Quest.

The other issue is the concept of format. VR allows autonomy as to where to look and what to look at, and theoretically that produces a unique experience for each viewer, since nobody can exactly replicate your head moving exactly. That often means traditional concepts of cinematography are out the window, as the viewer chooses their own adventure. So I find that my approach to VR differs from my other animations or projects. I conceive these works as if thinking of a still life, where the narrative exists but isn’t linear – it’s not spelled out; it is contained in the composition. This requires a higher effort from the viewer, who is not fed a linear story. But because the viewer is not passive to the story, their role in the experience shouldn’t be either.

What are your hopes / expectations for the Tribeca Film Festival’s new approach to programming? For the role of VR and similar technologies for the post-Covid cultural / artistic landscape?

Obviously there is a certain platform that comes from the physical attendance of people in your field, putting young creators in a room with industry favorites – particularly in a place like NYC. But the reality is that that’s not an option right now. Other festivals canceled completely, so the fact that Tribeca has not only not canceled, but changed the concept of the film festival, even if only for this year, even if only for this VR category, could lead to unprecedented opportunities. I am excited for people around the world to be able to access these films, to experience them from home, and naturally the potential reach is an exciting prospect.

The Tribeca Film Festival was born out of the only major tragedy in my lifetime [the events of September 11, 2001] that shook the world to its core at a scale that compares to the global pandemic we are living through. So it does not go unnoticed by me that the contributions to culture, art, and film that Tribeca brought about in 2002 really pushed the industry forward. A new phase where the resilience and grit involved in stimulating the production of extraordinary films from the depths of loss exclaimed to the world that not only would New York City be ok, but that art had fighting power. We are still unsure of how the impact of the current crisis events will evolve, but I feel pretty lucky to be able to be a part of the fight to push through the hardships of loss, isolation, and uncertainty, to be a part of adapting the festival so that it can continue to empower and reach out to people like it did in its first year.

Where do you hope to take this format / tech within your own practice? Are you working with any other new digital technologies that are particularly exciting to you?

I am interested in creating design fiction and cultural artifacts that comment on current notions of the body, of folklore, and of identity. The body is our interface with the physical, the virtual, and the spiritual, so our perception of these realms is directly related to how we see ourselves and others. This trifecta defines who we are, how we operate, what we work towards, who we are attracted to; it creates windows of opportunity, visibility, awareness; it affects all aspects of life. The tensions between folklore and behavior are super interesting in how we celebrate, who we idolize, what we replicate, why we worship. The digital contains the same rituals, but they are not claimed as folklore yet, so I am fascinated by creating cultural content that references what we know as traditional folklore and subverts it to represent new notions of body and identity, to redefine folklore for the future.

The process of collaboration brings new challenges that expand these ideas into unprecedented places, so I would like to team up with shamans, performers, poets, artists or stylists to explore new forms of fashion editorials, or to make totally fucked up body horror performance, dancefloor rituals, or virtual operas – whether that means using virtual reality, animation idents, experimental photogrammetry, or interactive installations. There is a lot of room to make things that are weird but that still feel strangely familiar, which is possibly the hardest combination to achieve. Punk metal, babes.