The Man Who Came From Hell

|TOBIAS RUETHER

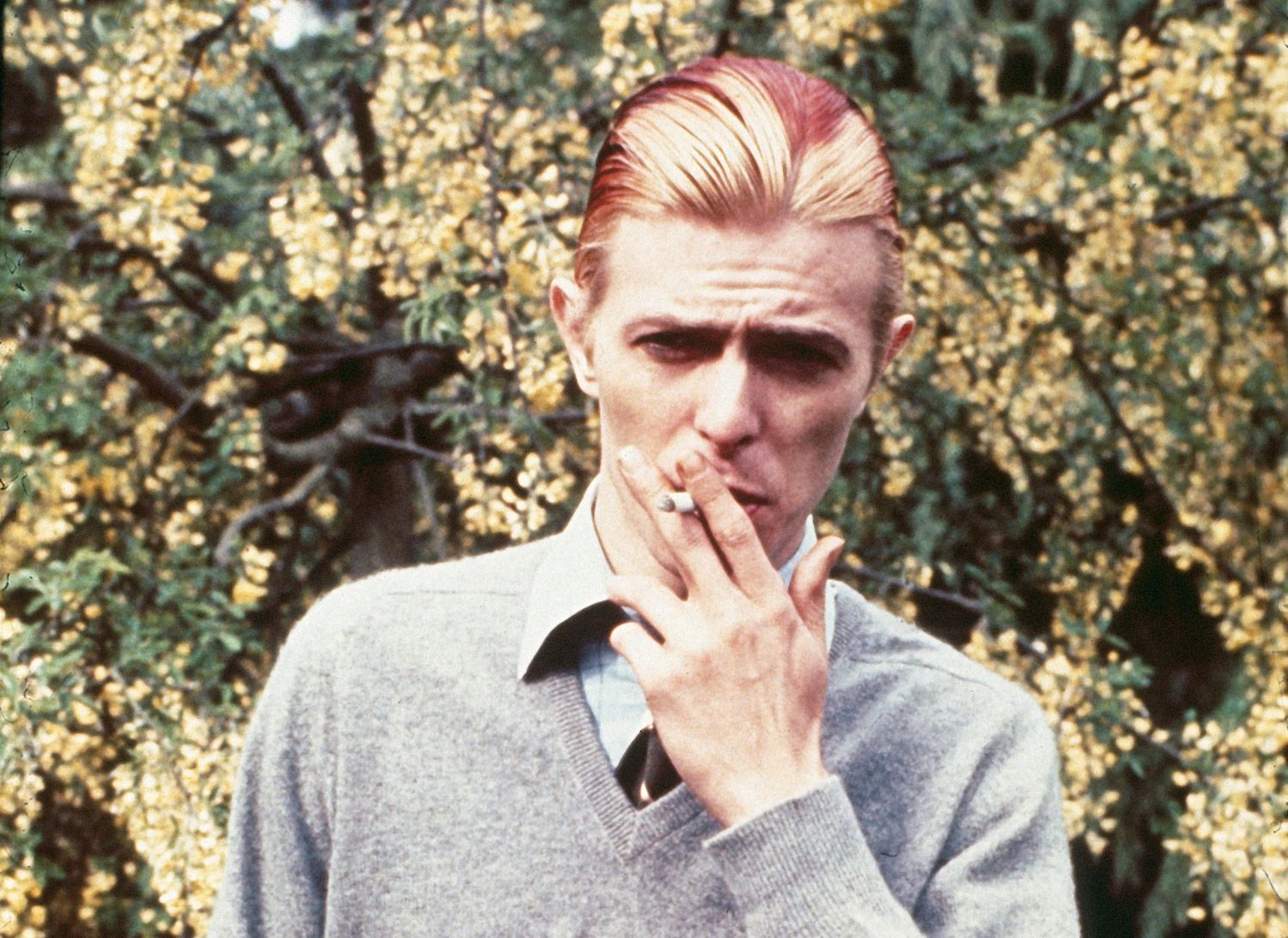

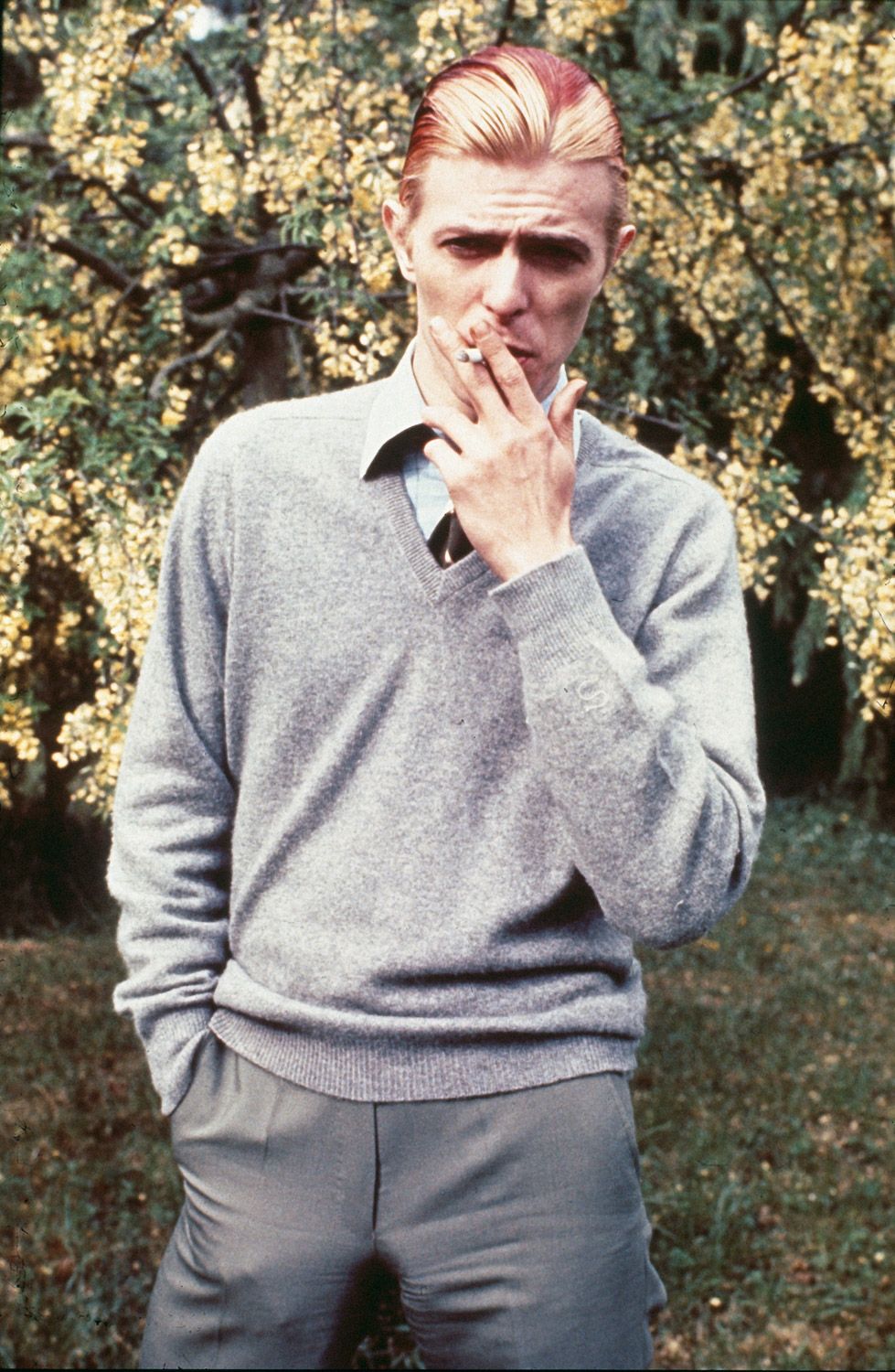

EXILE ON MAIN STREET: Thirty years ago, DAVID BOWIE moved to Berlin. He painted, he rode a bike — and he left behind “Heroes.”

David Bowie rode his bicycle a lot when he lived in Berlin. It was the summer of 1976 and he rode up and down Schöneberger Hauptstrasse, he rode to Kreuzberg, to the Exil restaurant and to the Hansa Studio near the Wall where it overshadowed the flattened, dead Potsdamer Platz. There, he worked meticulously with Brian Eno on new music. He felt so unbelievably free in Berlin, Bowie would say later, that he was gradually able to get away from cocaine and all the bad trips, away from Satanism and the persecution complex, from the fascistic fantasies of absolute power that had been plaguing him, from cabalistic mysticism, from the darkness – he had come back out through the door to hell, Los Angeles, where he had been looking for the Holy Grail and had seen ghosts and lived on milk, cocaine, and four packs of Gitanes a day. So it’s been exactly 30 years since David Bowie biked his way around the divided city of Berlin, since he haunted those clubs and gay bars, ate pâté on Wannsee, went shopping at KaDeWe, rode his bike a lot and showed the Berlin guys and girls, their long hippie hair just hacked off, just what sort of cool elegance their city was capable of. Or rather, how coolly and elegantly one could live in this imprisoned, demolished city, robbed of all its glamour, if one simply treated it as a stage and oneself as an actor upon it.

“The Actor”: that’s what David Bowie, the failed stage actor, called himself on early albums such as Hunky Dory. Since the very beginning of his career in London in the mid-’60s, he was always slipping into costume – mod, folk singer, hippie, Ziggy Stardust, the Thin White Duke – and none of it was authentic, all of it was show. But he hated Los Angeles, the capital of put-ons and shows through and through, where Bowie moved in 1975 to record his drug album Station to Station and to perform in the sci-fi film The Man Who Fell to Earth. It was via Los Angeles that he found his way back to Europe and looked in Berlin, the city always in the state of becoming but never in the state of being, for real life: “I thought I’d take all that stagecraft,” Bowie said, “throw it all away and live the real thing.”

“Since the very beginning of his career in London in the mid-’60s, he was always slipping into costume – mod, folk singer, hippie, Ziggy Stardust, the Thin White Duke – and none of it was authentic, all of it was show.”

Of course, he didn’t do that right away. First he moved into the luxurious Gerhus Hotel, now known as the Schlosshotel Grunewald, the hotel where the German soccer team stayed during this year’s World Cup. But then he moved to Schöneberg, to Hauptstrasse 155: seven rooms on the first floor, painted black, right across from a spare auto parts shop. He was 29 years old. Iggy Pop, his protegé, lived on the fourth floor and regularly emptied Bowie’s refrigerator.

Whoever goes looking for traces of Bowie in Berlin today won’t find anything. Bowie in Berlin is a fiction of the walled city, a myth. There’s a dental practice in his apartment in Schöneberg now, a tattoo studio beneath it and, to the left and right of the shabby building, a cell phone outlet, a Turkish fast food place, an oriental junk shop with water pipes, a delicatessen shop – and a gay bar, Anderes Ufer, now called Neues Ufer. Bowie was a regular there. Ate bean soup, drank whiskey. He practically fell into the place whenever he left his apartment. Or so goes the myth.

In wicker chairs in the half shade in front of the Neues Ufer now, a woman reading die taz drinks her afternoon beer and watches the traffic sweep past the Kleistpark subway station, heading east. Comfortably lazy West Berlin is at home there. The better quarters of Schöneberg are more likely to be found on the other side of Hauptstrasse, towards Nollendorfplatz, a fashionable gay neighborhood. If you ride (like Bowie, on a bicycle) further east, past the five hundred rental apartments of the Sozialpalast and under the elevated train, you soon arrive at Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie, Scharoun’s Philharmonic Hall, and the new Potsdamer Platz, the cheapest set designed in the Berlin Republic: screwed-up new buildings, a musical theater, a bland shopping mall, the headquarters of Deutsche Bahn.

Back in the summer of 1976, the Platz lay flat and empty, dominated by the Wall, surrounded by watchtowers. “Hansa by the Wall” is what David Bowie called the studio on Köthener Straße on his two Berlin albums, Low and “Heroes.” Low, perhaps the most radical departure from top-40 music ever dared by a superstar, was actually recorded at the Château d’Hérouville, a castle near Paris. Bowie then mixed it in Berlin, vis-à-vis the Wall, its shadow cast over the electronic, desperate, claustrophobic music of Low. “Weeping Wall” was the only track on the album recorded here. If Bowie really was feeling better in Berlin, you couldn’t hear it on Low.

“Whoever goes looking for traces of Bowie in Berlin today won’t find anything. Bowie in Berlin is a fiction of the walled city, a myth.”

Then Bowie grew quieter and quieter. This splendid singer – who, in February 1968, had written English lyrics for the French song “Comme d’Habitude,” which were rejected in favor of other lyrics, the ones Frank Sinatra would make immortal with “My Way,”– wasn’t singing anymore. And when he did, it was in broken lines like, “Sometimes you get so lonely / sometimes you get nowhere / I’ve lived all over the world / I’ve left every place,” or something about breaking glass in his baby’s room again. His marriage to Angela was coming to an end. He broke up with his manager. The less he did coke, the more he drank. He was going down, deeper and deeper.

But he was also unbelievably productive. Bowie, supported by experimentalist Brian Eno on synthesizer and later also by the exceptional guitarist Robert Fripp, composed art. He cut tapes apart with Eno and glued them back together again, prepared the guitars, strained the saxophone, sang in tongues. It’s bitterly cold, homeless music, a knocking and pounding from the underground. “Subterraneans” is the last song on Low. Bowie says it’s about “people caught in East Berlin after the division of the city.” The record was completed on November 16, 1976, in the most miserable month of Berlin’s calendar, but it took the unsettled record company until January 1977 to release this electro-smog.

Bowie wrote the hit his record company was waiting for with his next album, which appeared just three quarters of a year later. With the stirring “Heroes,” Bowie’s years in Berlin finally became mythology. “I saw two lovers who met every day at the Wall,” he said later. “Why there, of all places? Maybe out of some sort of feeling of guilt, and so, this heroic gesture: to look this absolute lovelessness in the face. But maybe I’m nuts, too. Maybe the two of them just worked nearby.” Kennedy left four words to the walled-in Berliners; David Bowie this hymn.

If only Bowie hadn’t placed quotation marks around “Heroes.” It’s not to protect himself from pathos; it’s an artistic gesture. Bowie is playing, as always. He’s quoting. The move to Berlin was just one of his postmodern escapades, inspired this time not by Oscar Wilde or Stanley Kubrick, whose film 2001 sparked Bowie’s worldwide hit “Space Oddity,” but instead by Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin, Bob Fosse’s adaptation of which, Cabaret, had arrived in theaters in 1972.

“He didn’t have anything to do with Berliners, either. He liked them because they so flippantly looked right past him, and in the depths of his paranoia-stricken drug days, that was just what he wanted.”

Bowie met Isherwood during a concert on the Station to Station tour in Los Angeles in 1976. Isherwood had lived at Nollendorfstrasse 17 back in 1929, not even a kilometer away from Hauptstrasse 155, where Bowie would grow a beard and pick up painting again. Bowie pressed him for Berlin anecdotes, but Isherwood advised him not to go; the city had long since grown frightfully boring. “Young Bowie,” he said, “people forget that I’m a very good storyteller.” Sally Bowles and the party before the storm – all invention? Even better. Bowie moved – and found his Sally Bowles in Romy Haag, the reigning monologist of West Berlin. Her nightclub, Chez Romy on Fuggerstrasse, was something along the lines of Sally’s Kit Kat Club. If one knew how to use one’s imagination. If one cared to.

And Bowie did. He lived out the dreams of his youth in Berlin. “The first film that ever moved me,” he once said, “was The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. I was around fourteen. Later, I saw M and Metropolis and films by Pabst, Murnau, and they all came from Berlin.” He became enthralled with German Expressionism, rode to the Brücke Museum in Grunewald, and painted: a child in the stairway, a Turkish father with his son, Iggy Pop in front of bare trees, and halfway decent imitations of Müller, Kirchner, and Heckel, whose 1917 woodcut portrait of Kirchner, Roquairol, is mimicked on the cover of “Heroes.”

In David Hemmings’s 1978 Berlin film Just a Gigolo, Bowie plays a Prussian officer back from WWI, vulnerable to Nazis and women. It was drama of decadence and a grand failure, “all my 32 Elvis Presley films in one go,” Bowie has said himself, but even so: it was Marlene Dietrich’s last performance on film, Bowie at her side. He had pulled off his masterpiece. “A New Career in Town” is the most beautiful instrumental track on Low; it’s the theme song of Bowie’s years in Berlin.

But even alongside Marlene Dietrich in a film, he was again only a part of the scenery. The reality of Berlin between 1976 and 1978 was punk and Christiane F. But this was more the reality of Iggy Pop, who was punk even before there was such a thing as punk and did not, in fact, like Bowie, come to Berlin as a dandy in the making, but to “shoot drugs in the heroin capital of the world.” Which he did. Bowie’s contact with this world was sporadic at best, cut off as he was while he worked in the studio according to a precise schedule.

Even so, Bowie and Iggy Pop showed up for the August 12th, 1978 opening of the legendary punk club SO 36 on Oranienstrasse in Kreuzberg. They slid up, as Thomas Schwebel recalls, “in a cream-colored Mercedes. Bowie looked like complete shit with his toned glasses and white suit. Like some toothpaste salesman.” Everyone threw themselves at Bowie and Iggy Pop disappeared into the men’s room. Later, Iggy alias Jim Osterberg was said to have told jokes about Jews, “and this from an American Jew,” Schwebel says. “Not one German flinched, but the two of them laughed themselves to death.”

They’re said to have laughed a lot in the Hansa Studio as well. But even if Bowie tended to shoot off at the mouth quite a bit in those days, he wasn’t entirely comfortable in the city, either. Once, from the fourth floor, the Berliner sound engineer provoked the East German guards in the watchtowers on the other side of the Wall – Bowie and his producer, Tony Visconti, panicked and ducked under the mixing board. Today from the fourth floor, you see the Deutsche Bahn Projektbau GmbH across the colorless Potsdamer Platz, the Debis tower, the underbrush on the abandoned plot by the subway station.

Deathly boring in the steely July sun, but they all came in the ’80s anyway. First Depeche Mode, then U2 and Nick Cave. They came to seek out the magic Bowie had found here and maybe even left behind. But there was nothing here, which is why U2’s Berlin albums, Achtung Baby and Zooropa, are big, embarrassing heaps of graffitis-prayed Trabis and pseudo German. Depeche Mode at least found industrial sounds in Berlin, recorded earlier by Einstürzenden Neubauten, and they sampled them for a big hit, “People are People.” But Bowie had nothing to do with any of that.

He didn’t have anything to do with Berliners, either. He liked them because they so flippantly looked right past him, and in the depths of his paranoia-stricken drug days, that was just what he wanted. Lodger would be his next album in 1979 – Berlin songs, but recorded in Montreux. “I didn’t plan to leave Berlin,” he says, “I simply drifted away. Maybe I was feeling better.” On top of that, he landed a role in a theatrical production, The Elephant Man, in Denver, Chicago, and New York, his first real onstage success. “Then Berlin was … over.” And just as he came, Bowie moved on, an actor between roles.

Credits

- Text: TOBIAS RUETHER