Bad Principle Created Chaos, Darkness, and Woman

|LUCY BROOME

Encased in the unglamorous accolade of Friday night’s residual alcoholic perfume, holed tights and stained shirts might indicate a state of decline to some, or rejuvenation to others. We are no stranger to the narrative of the beauty filter. The often-controversial digital application penetrates the barrier between cyberspace and IRL, often influencing how the femininely inclined navigate their self-presentation. Though used to bending to societal norms of presentation, the digital advent brings the addition of a whole new set of instructions. It can be petrifying female and, as Harley Weir tells me, perhaps even more sick than its male counterpart.

"The future finds my blank.

I’ll take it from Mr. Rashid the LASIK surgeon with his pudgy

fingers, I’ll take it on my cheek as he pulls back my lids,

Hairy knuckles, pink shirt, sistine Madonna cherub cufflinks.

The ladies firm hands at customs.

The gritty shovel hands on the dance floor.

Uber can wait, I’ll have one last go and the finger that comes out

is red.

Mothers fury.

Like clockwork.

soften a murder.

And now that it’s here I’m clear.

All fine no sex, no fire, no thought.

Guided by the moon, adamant and sure that teetering on the fence

is certainly the answer for my hot little sorrow.

By a house. Reach a goal. Any hole. O the cars that make it glitter

here. A girl from the jungle. Polytheist aggression once monthly

with a handful of everything."

— Extract from "Code Red," published in Beauty Papers.

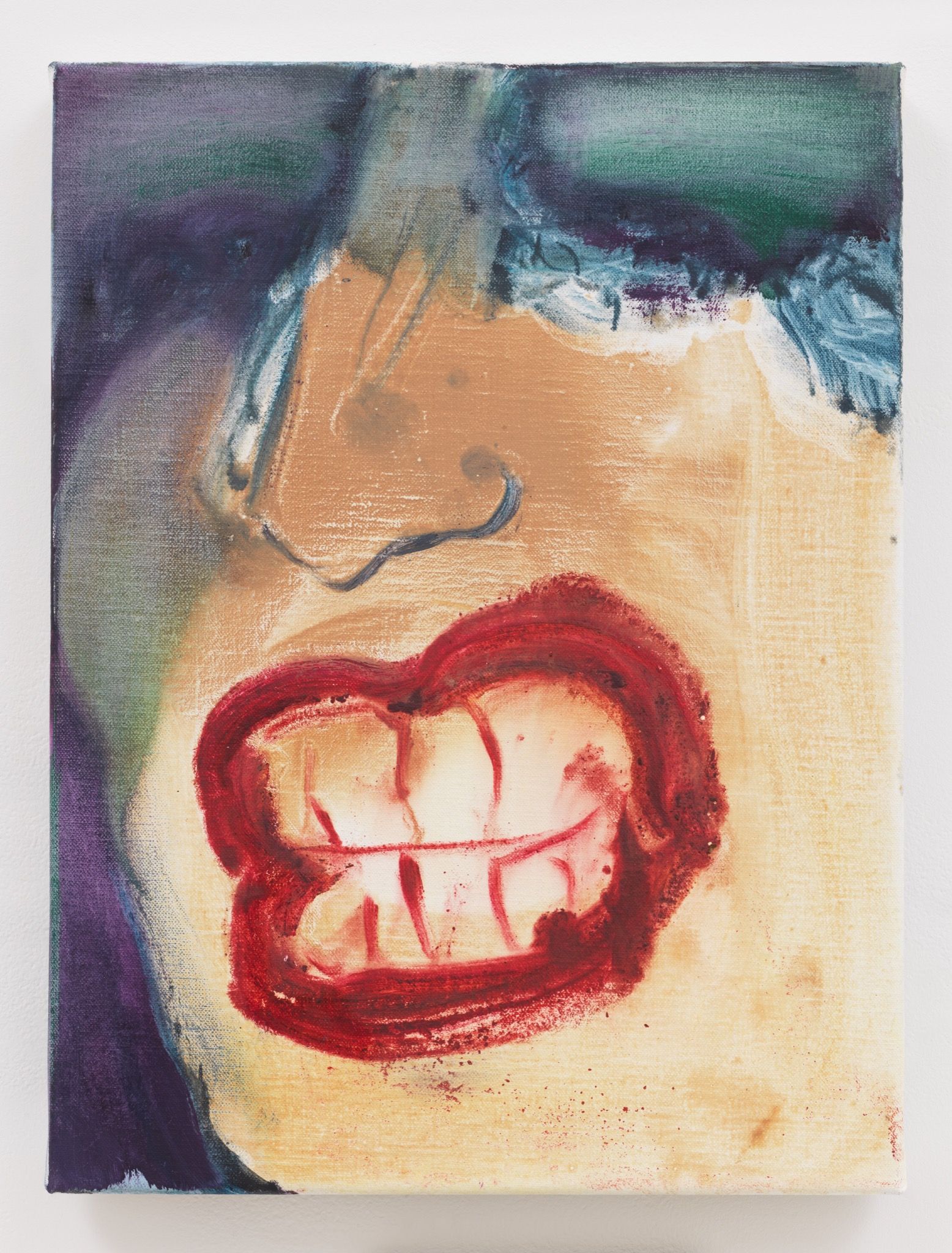

Harley Weir recently posted her face on Instagram for the first time, a revelation that coincided with the publication of her new book, Beauty Papers. A central element of her work is a macro-focus of the feminine image — an orchid dripping with a benign translucent fluid has the same sensorial affiliation, as another flower with a bespoke intimate piercing. The focus is often configuring connotations and denotations that tap into the wider idea of the Weir-woman. The recent unveiling of Weir’s face was not made unaccompanied — a three foot tall nearly identical twin doll sits upright, beside Weir at the press event for her book. The doll, who remains unnamed at this time, came dressed in a matching KNWLS ensemble. In one image featured in Beauty Papers, Weir is suspended opposite the doll, by the Japanese bondage rope tying technique of shibari. She pulls the inanimate figure towards her in a sweet caress as her hair trapes along the floor. The dolls eyes remain open and unblinking. The image is set against a close up of the doll’s gnarled and twisted fingers, topped with acrylics, on the following page.

LUCY BROOME: I noticed that you had this doll, a twin of yourself —

HARLEY WEIR: She wasn't exactly my twin, but she was dressed that way.

LB: Who is this person if she's not your twin?

HW: She was trying to be my twin. She featured heavily in the book, and that was her last outing as my doppelganger.

LB: Did she ever have a name or was she nameless?

HW: She was nameless. She was left over from a Vogue shoot from a couple of years ago. I didn't have the heart to sell her. I felt there was a need for her, and there was. Her place in the book was to eventually become me after I had shredded all my functional imperfections and become the ultimate beautiful object.

LB: In terms of this beautiful object, this can be derived from the feminine perception. With that in mind, would you say that part of the innate female gaze is horrific?

HW: I think every woman has a different vision of what they find beautiful. Obviously, the gaze can be horrific — or not, it just depends. I thought it was odd that a lot of people saw the images and were like, “Oh my god!” I was thinking, I’m not even going full pelt here. This is light, this is fashion. But people saw the grotesque and vulgar side of the shoot, which I hadn’t noticed right away. Since I'm in the images I was able to take things to a different place. Usually, I have to rely on someone else’s image and consider their feelings in doing certain things, which often holds me back. In these images I was able to go a little harder and look at myself through the largely false gaze of fashion and laugh at the silliness of it all.

Weir’s works are situated within a wider legacy of uncanny feminine presentation in photography. She demonstrates a hyperbolic dictation of the performance’s women undergo, also seen in the works of other contemporaries such a as Nadia Lee Cohen or Juno Calypso. A common characteristic of these artist’s respective practice is that though the photographers themselves are present in the images they produce, they are seemingly not there. There is a glammed up, or grossed up, apparition that takes the stage in a theatrical manner, the product of a recycled and contorted conception. The product is a gaze that has changed so many hands, it lands in a violent form of female looking, pushing an ultra-exaggerated form of anything that was thought before to enhance attraction. Misogyny associates a grotesqueness to the female image, linking the internal detritus of the body, blood, sweat, tears, excrement to the exterior. The poem at the start of Beauty Papers, "Code Red," was named after the lyrics of a Notch reggae song “Never sex a gyal when she under code red.” Weir explains to me the circumstances under which she wrote the poem.

HW: To put it bluntly, it was PMS. It was me trying to describe those mildly crazed feelings before a period, where everything seems to matter, and I become passionate and horny as hell fire. The period arrives, there’s this release. I find myself extremely creative in these moments. I definitely like to utilize it in an artistic way if I’m not blubbering too hard into my phone.

There's a lot of offence over periods. In most cultures around the world there’s a stigma of some kind, often derived and backed by religion. Funnily enough, I took the title “Code Red” from a song, “Nuttin Nuh go so” by Notch “And yuh never sex a gyal when she under code red.”

LB: Do you have any specific examples that you've read?

HW: In the Bible, Qu’ran, and Torah. In fact, in almost all religions they present very similar stories, often where the female is not pure whilst on her period and advises men to keep away. In the Bible it suggests that women were given period pain to punish their apple eating sins. Back in Genesis 3:16 God curses Eve: “I will make your pains in childbearing very severe.”

It’s interesting when you look back to ancient history and folklore. Women and their bodies seem to be a lot more praised. It’s such a shame that in recent history, we've been given women so much shame for those things that allow our bodies to function and in such a glorious way.

If Rei Kawakubo’s mode of communication was clothing, then Weir’s is the camera. An opening image from Beauty Papers depicts Weir with an arched back, accentuating the silicone breasts she has stuffed down a mesh bra, and pillow to the rear, shoved down a pair of cyan blue tights. Reminiscent of Kawakubo’s approach toward adorning the female body, the incorporation of lumps and distortions in the image make the female form seem alien, whilst simultaneously playing on its expected proportions.

The camera, in a historical sense, has been an extension of the very male optical organ, as being a mechanical device. Unlike fabric, it denotes some innate masculinity. As established male gaze theories suggest, the male gaze is innately objectifying, rendering subjects as objects. The classicist on gaze, John Berger, says, “men act, women appear.” Male existence dominances female existence. Women only appear in relation to the male narrative, often absence of formulated identities of their own. In the case of the camera, the photographic gaze — in terms isolated from gender politics — taps into Foucault’s idea of gaze as surveillance. It encompasses its own power and control, often forcing the subject into a passivity through its ability to create a literal object, a literal mark in time, as a captor of existence.

In photography, when the female gaze subverts this pre-disposition, it incorporates the presence of another viewer and pursues a performativity that actively acknowledges being looked at — and stares back. It laughs at the conventions of societal beauty standards and either grossly exaggerates them past the point of male delectation, making the hypersexual hyper grotesque, or in the legacy of Cindy Sherman, plays into the caricatures that are often placed on women.

Leaning into these constructed ideas of their identities facilitates a reclamation that delivers a feminine agency and taps into a shared feminine experience: the performance of everyday life. Women partake in performance to fulfill social constructions of what women ought to be, oftentimes in their relation to how they benefit men: cool, shy, sexy, smart, cunt, bitch, whore, or Madonna. Playing into these roles is perhaps universal feminine experience.

HW: It definitely comes from a place of disgust, perhaps men’s disgust at the functioning female body. A sad misunderstanding that’s turned our bodies into decorative objects. But now, I feel it’s gone beyond a man's point of view, and I think we're actually doing it out of habit and for each other and ourselves, in some kind of twisted semi empowered semi slave sort of way — but It’s hard not to perpetuate it a little, for I certainly don’t know a world where it’s any different.

Credits

- Text: LUCY BROOME

Related Content

DUA LIPA, At Your Service

Photographic Performances: CHARLOTTE JAMES and CLÉMENTINE SCHNEIDERMANN

The Principles of Trap Feminism

“The Nakeds”: Exhibiting Nude Drawing in an Era of Digitized Sexuality

On Time: HONEY DIJON

You Could Almost Call It Grace: MARLENE DUMAS in Conversation with HANS ULRICH OBRIST and VIRGIL ABLOH

DEANA LAWSON: The Selection of Images

Mixtapes and Meta-Hacks: GUCCI CIRCOLO Berlin