As Long as it Lasts: Ari Versluis

|ORSON GILLICK MORRIS

In 1993, Lawrence Weiner’s AS LONG AS IT LASTS was installed on the Rotterdam Euromast overlooking the birthplace of gabber, Club Parkzicht.

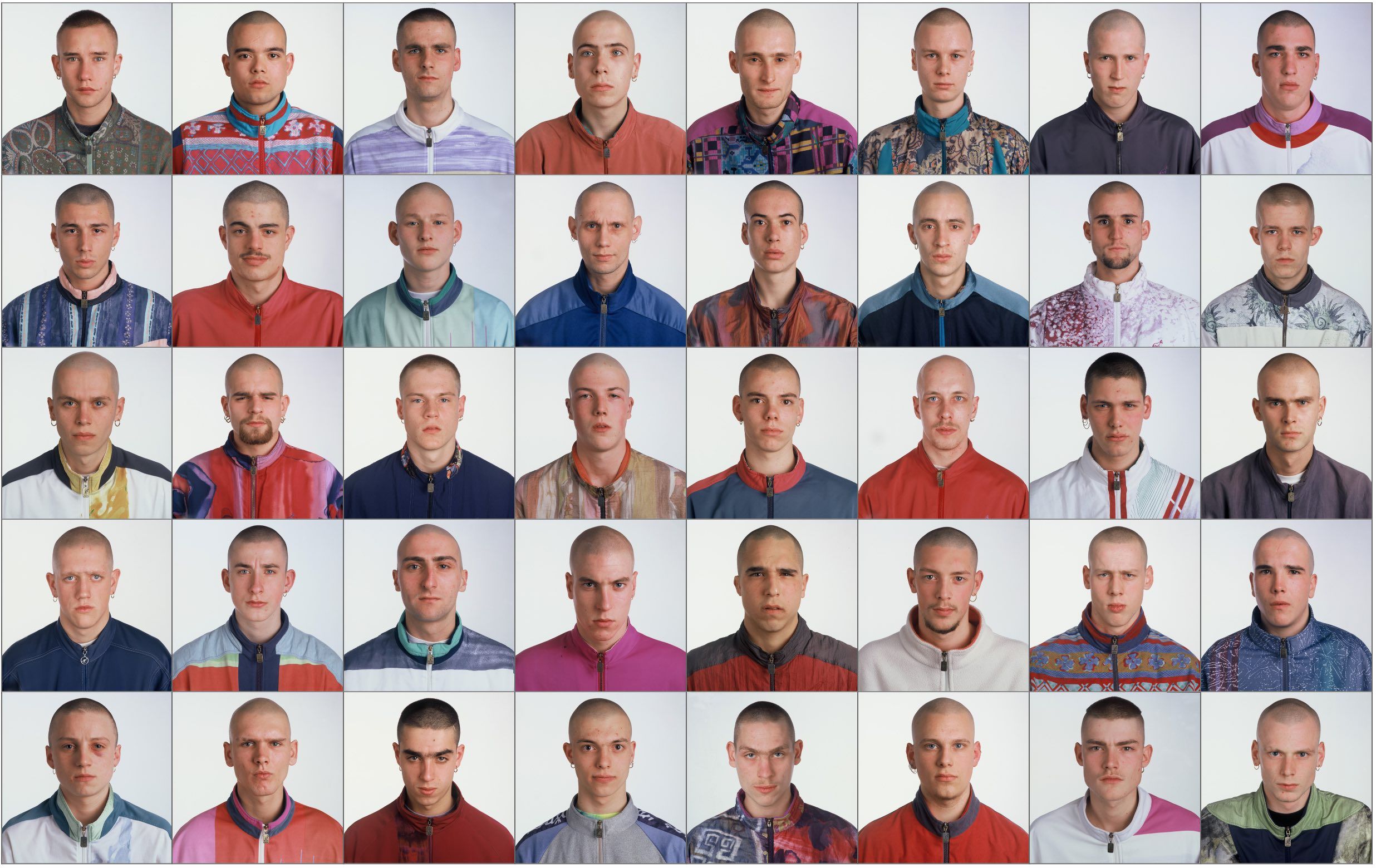

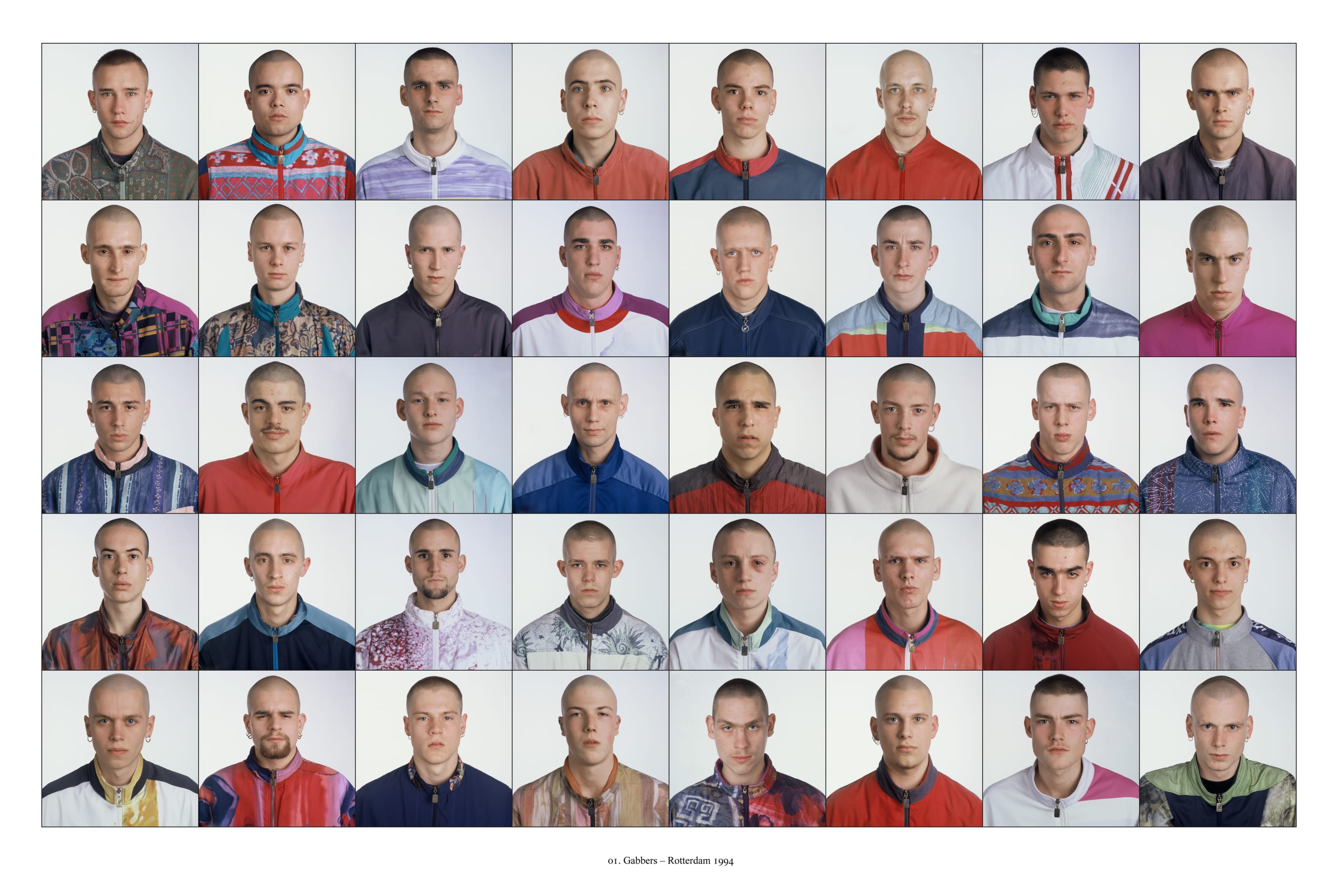

A year later, Dutch photographer Ari Versluis began the project Exactitudes in collaboration with Ellie Uyttenbroek to document the inception of the scene. Versluis invited individuals he met back to his studio—on the condition that they wear the same outfit—to be photographed and categorized according to their “social uniform.”

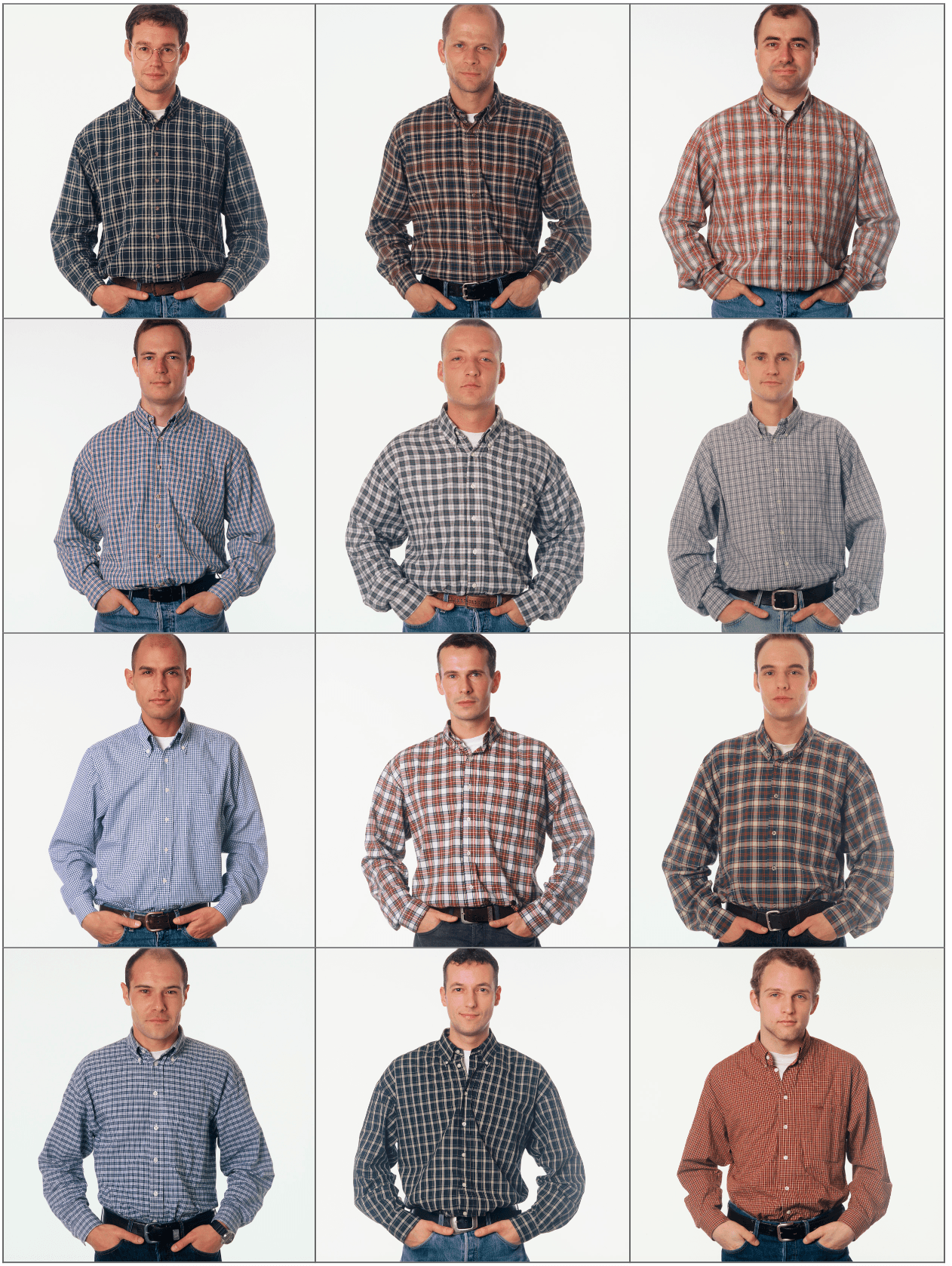

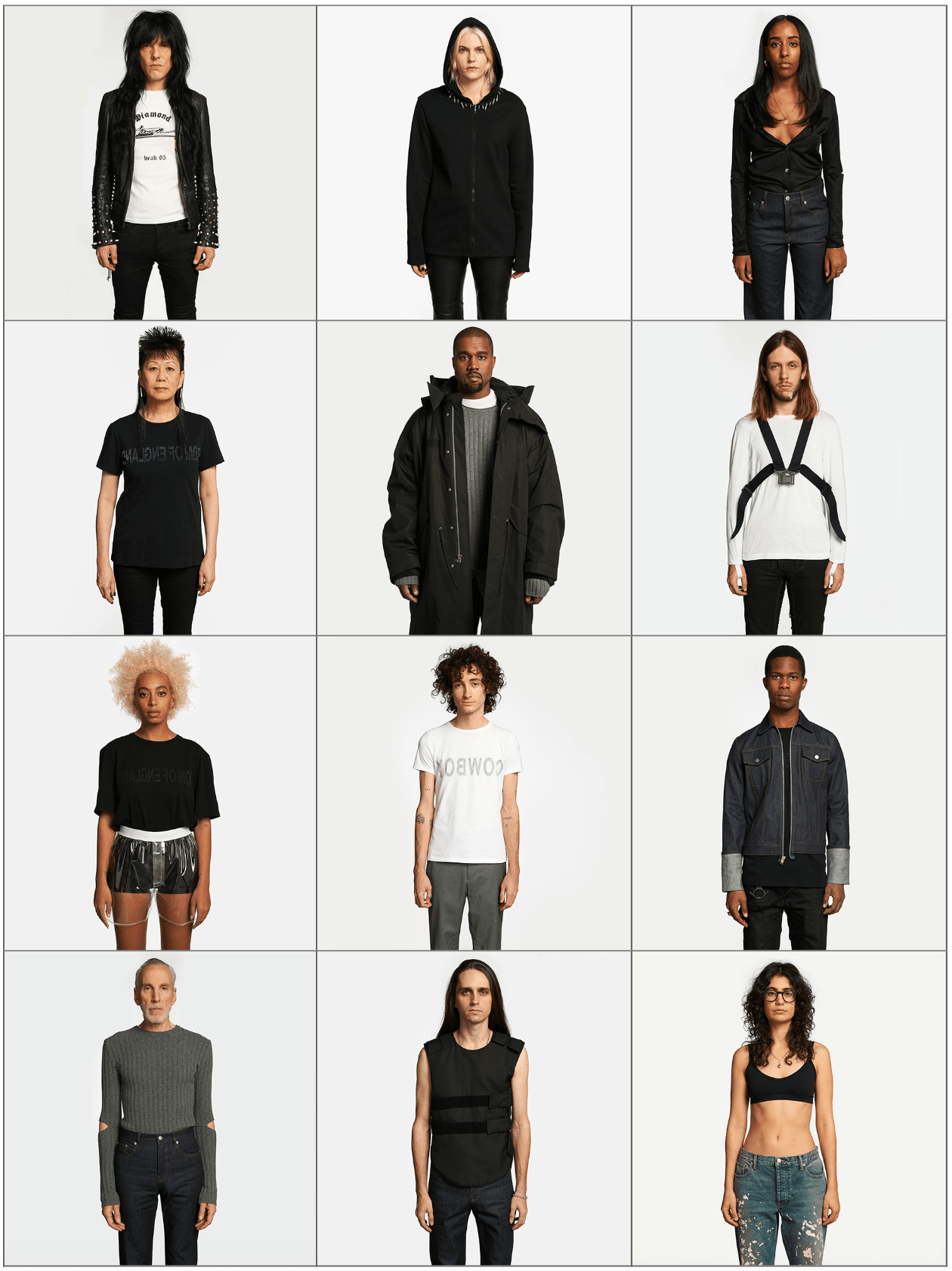

30 years later, Exactitudes is still an ongoing artwork—each installment is a grid of portraits defined by a “social categorization”: Gabbers (1994), Casual Queers (1995), Speedfreaks (2002), and Y2K Z (2022). Even the individualist Ye is defined by the caption Helmut Lang Fans (2018).

In contrast to Exactitudes’ anthropological portraits are the intimate shots of the Versluis’ exhibition “Proximity” currently on view at Schlachter 151 in partnership with Timberland. Shot primarily on the street, this archival material brings fragmentary moments from Rotterdam’s gabber scene into dialogue with the present. In his work, it is as if Versluis himself is investigating the identity, uniformity, and duration of the subculture as long as it lasts.

Ari Versluis and Ellie Uyttenbroek, Gabbers (1994), Exactitudes.

ORSON GILLICK MORRIS: Was “Proximity” conceived for the exhibition space or was it an ongoing project?

ARI VERSLUIS: It is a research project that I am working on—the exhibition is a good moment to try to conceptualize spatially what I’m doing. “Proximity” is part of a work in progress to make my archive productive for the next decade. It probably has to do with getting older, trying to get a grip on what you did with your life. How many people did you meet? As a photographer, you will remember them quite well—they are somewhere in your brain. You will meet them again, but in a new constellation.

OGM: Is your photographic practice sensual, systematic, or both?

AV: It is always about the real contact that you have. It comes mainly from the street. It comes from being out there. Your eye needs to wander. You are a voyeur. You see people who catch your eye and you approach them. And then, of course, the systematic part is what you do with these photographs. How do you archive your work within a creative and visual strategy? This challenge has been with me for decades.

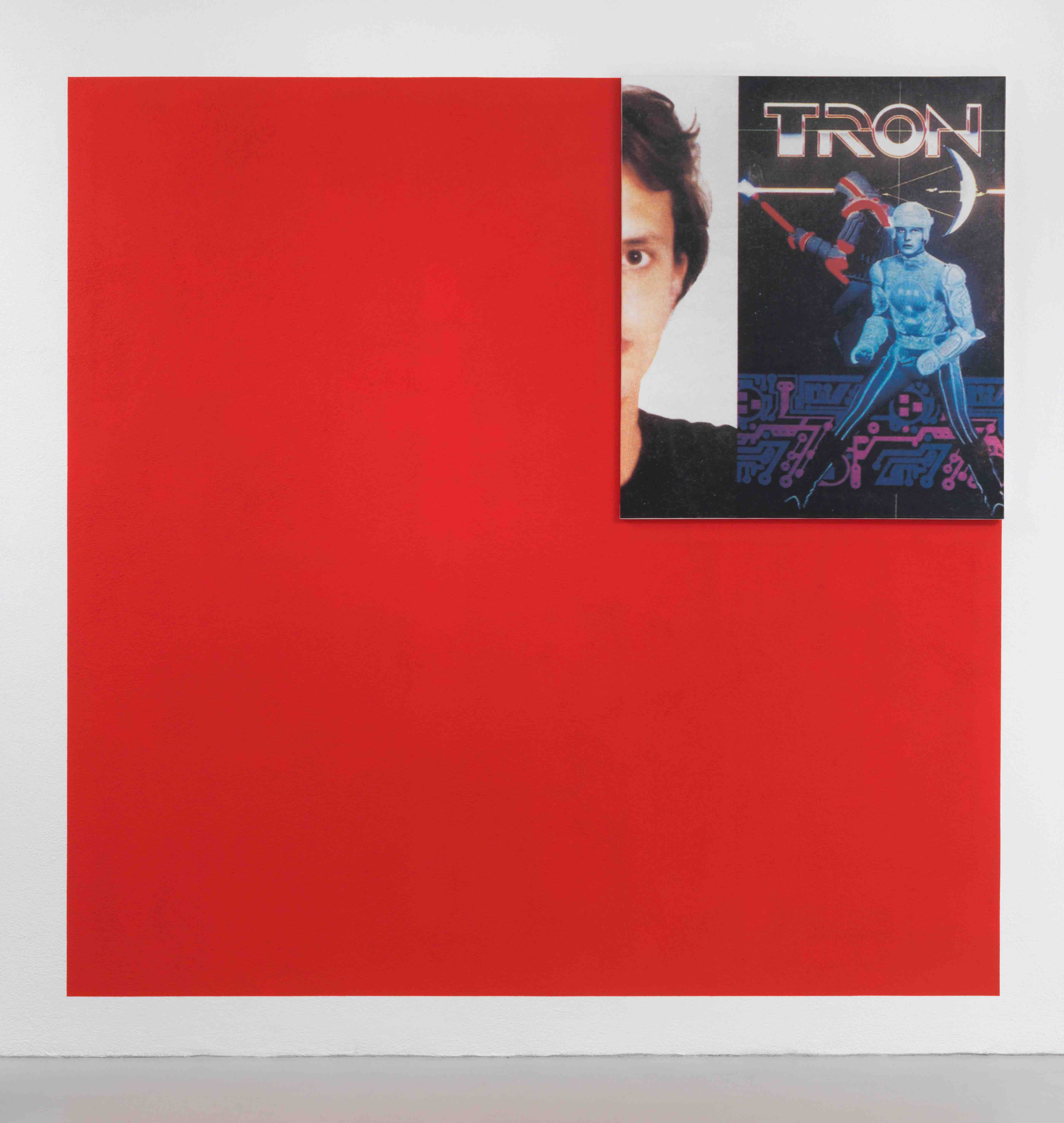

Portrait of Ari Versluis at “Proximity,” Courtesy of the artist, Schlachter 151, Timberland, and Numéro Berlin. Photographed by Ronald Dick.

OGM: How do people construct an idealized version of themselves?

AV: That is a completely different story nowadays. Now, everything is ten times more performative. People know exactly what a camera does. They also understand what an image does. I think this is so relevant to understanding the culture you’re in and the culture back then when social media didn’t exist. Even in the late 90s and early 2000s, when a lot of the work in “Proximity” was made, people had no smartphones.

OGM: So self-idealization has changed?

AV: Now, you are very much aware that there is a viewer. That is a huge difference. When you are aware of a constant viewer, it creates anxiety around the fact that you are viewed. That is the difference, I think.

OGM: Does this idealized version of oneself always conform to a certain categorization?

AV: With the progressing of time, subcultures change. There were once mainstream ways of manifesting yourself and now you manifest yourself through a niche. That had a lot to do with how you perfect yourself. Back then, you wanted to be more tribal. Now you only want to be in that niche—that is the big difference. People want to be safe in their niche. That is a total obsession now. People didn’t care about safety before—they took far more risks.

Ari Versluis and Ellie Uyttenbroek, Casual Queers (1995) and Helmut Lang Fans (2018), Exactitudes.

OGM: How are the portraits in Exactitudes individualistic yet uniform at the same time?

AV: With Exactitudes, maybe twenty percent of the work is about subcultures, and the rest is just the artistic eye—a way to look at society.

OGM: Was the work in “Proximity” mainly photographed on the street?

AV: It’s done everywhere, in metro stations, in clubs, in public space, and sometimes in the studio. I always had a small analogue compact camera with me, it fit in the pockets of my trousers. I did it more as research. That is the difference between “Proximity” and Exactitudes. Exactitudes is a far slower, collaborative process with a very specific end result in mind.

OGM: Is the use of a white background in Exactitudes related to it being an anthropological project that documents people and social categorizations?

AV: Yes. It’s a perspective from anthropology, but also a look at society. It’s a method of working with the concept of isolation. This offers a perfect way to look at consumer culture. Of course, you don’t want to over theorize what you do but it’s part of the practice. I also try to use this perspective when I do fashion photography. But above all, I want the people in the shoot to be portrayed for real—a mirroring effect on both of our realities instead of just looking at them.

I saw this article in Flash Art with these two people and the headline: “Only one of us is real.” That was so fantastic, because you really start concentrating on those images. “Who’s not real?” And then you notice it’s just an LA sentence. A very good illustration of how we look at images now because you practically don’t care.

I speculate that AI will create the death of the internet. I think it will probably happen. When you see so much, why bother looking? Why open your heart to it? In the end, it’s about sensitivity.

Ari Versluis, “Proximity,” 2024. Courtesy of the artist, Schlachter 151, Timberland, and Numéro Berlin.

OGM: You said in the past, “There are hardly any places where you don’t consume.” How does this apply to your photography?

AV: That is very interesting in relation to “Proximity.” At that time, people had the cities—the public spaces were theirs. Nowadays, you would be shocked to know how many public places are actually private. Places that you think are public. Where there are surveillance cameras. There’s no space to play—not in clubs, not in public space. You can’t experiment and make mistakes and see the beauty and value of it. You can’t take your time with anything. Space is super important.

“Proximity” is also about going back in time and going back to what it was when the digital world was absent. Where you did not immediately check somebody out online. It used to be “I’ll see you later,” right? You went to the same places to hang out and do your thing. You did not have multiple personas from one bedroom.

OGM: I don’t see a resolution to that.

AV: I don’t see one either. But a true culture is where people from every walk of life meet each other and feel that they belong. We love to talk about liquid times or liquid modernity, but you need to be quite a good surfer to float.

Vetements FW-17, Centre Pompidou, Demna Gvasalia.

OGM: The aesthetic of Rotterdam gabber was referenced and appropriated in Raf Simons’ SS-00 Summa Cum Laude and Vetements’ FW-17. How did Exactitudes make something fashionable that was once ridiculed?

AV: In Exactitudes, we were the first to look at gabber from a fashion perspective. You immediately saw the tribal-ness of gabber and its potential. While society perceived it at that time as right wing, aggressive, and drug confused, it was pure creativity. The amount of record companies that started, the graphic design that emerged, and everything else—it was a fantastic time.

OGM: Demna has a self-proclaimed fascination with social uniforms, and Vetements’ FW-17 is a direct reference to Exactitudes. Did you attend that show?

AV: No, we didn’t. We knew about it. Demna gave me a call and we talked about the challenges of the show and the relevance of social identity to his work. The show was very good—it had the right feeling to it. Appropriation is what it’s all about. Everything in fashion is appropriated. It’s cyclical in that way. When you look at appropriation from an art point of view, you would think, “that’s problematic.” When you look at appropriation from a fashion point of view, you think, “I can understand that.”

Lawrence Weiner, AS LONG AS IT LASTS (1993), Installation view, Euromast, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1993. Courtesy of Gladstone Gallery.

OGM: Lawrence Weiner installed an artwork in Rotterdam on the Euromast: AS LONG AS IT LASTS (1993). Do you remember it?

AV: Absolutely. Lawrence was just in time to do this, and it really worked. It is a characteristic of Rotterdam that they really embrace what is happening in the public space. Lawrence felt that. He felt that this work would be embraced by people.

OGM: AS LONG AS IT LASTS (1993) could be a metaphor for the eventual death of the gabber scene in Rotterdam.

AV: This tunnel below the Euromast is magic—this is the tunnel to the south of Rotterdam. And to the left is a big park that was almost always empty. The park was forgotten and then a club started in it called Parkzicht. Nobody complained about the noise because it was an empty park. A lot of the boys at Parkzicht came from the other side of the tunnel—that’s the poorest part of the town, Rotterdam South. The south side is still the rough part and still the interesting part. That’s where new things happen on the street. The other side is completely gentrified.

Parkzicht came and that was the birth of gabber next to the Euromast. The first gabber record was from Euromasters titled Amsterdam, Waar Lech Dat Dan? (Amsterdam, Where’s That?) (1992)—on the record cover you see the Euromast pissing on Amsterdam. It’s a “fuck you.” Amsterdam is and always was the cultural heart—and the place where house music flourished. But the gabber boys were always refused at the doors there.

Credits

- Text: ORSON GILLICK MORRIS

Related Content

Productive Narcissism

Where Does The Puppet End And The Human Begin?

The 154 Exactitudes of Ari Versluis and Ellie Uyttenbroek

Reinventing Mike Kelley

“I Don’t Want Anything”: An Interview with ECCO2K

DEAR MICHEL MAJERUS (1967–2002)

All Networks Lead Through Kansas: The Text Image

The Zone

Enter the Rave Continuum

How Does Design Contribute to Human Catastrophes? Gonzalez Haase AAS

Drain Gang

Harry Nuriev’s Critique of the Industry